Paul Kraus (born 1944) is a Holocaust survivor and mesothelioma patient. Kraus was born in and survived a Nazi forced labor camp during World War II.[1] In 1997, Kraus was diagnosed with mesothelioma, a type of cancer caused by asbestos.[2] Doctors originally believed that the cancer was terminal and he had only weeks to live, but Kraus is now considered to be the longest-lived mesothelioma survivor.[3] Today, Kraus is an Australian author and cancer survivor whose writings focus on Australia, health, and spirituality.[4] His book Surviving Mesothelioma and Other Cancers: A Patient’s Guide is a best-selling book on the subject.[1]

Paul Kraus | |

|---|---|

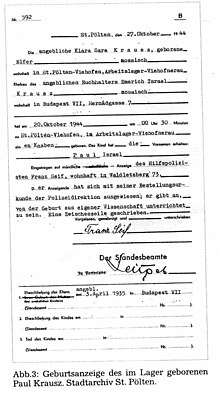

Paul Kraus's birth certificate (St. Pölten, Austria archives) | |

| Born | 20 October 1944 St. Pölten, Austria |

Viehofen Forced-Labor camp

editPaul's mother, Clara Kraus, a Hungarian Jew, had a two-year-old boy, Peter, and was pregnant with Paul when the Nazis deported her and her children to Auschwitz concentration camp.[5] Due to rail destruction by Allied bombing, they were sent to a forced labor camp established in the Viehofen flood plain near St. Pölten, Lower Austria.[6] Approximately 180 men, women and children lived in three barracks in the camp where they were used as forced labor for the state-owned Traisen-Wasserverband company based in St. Pölten and the surrounding area.[6]

Paul Kraus was born on the grounds of the camp on 20 October 1944.[5] Inadequate nutrition, lack of hygiene, shootings by the SS, failed attempts to escape, and bombings by the Allies caused many deaths at the camp.[6] Clara Kraus escaped with her toddler Peter and infant son Paul in January 1945 and survived a cross-country trek in winter to Clara's home in German-occupied Budapest.[5] There, she was reunited with her husband, who survived imprisonment in the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp. At the end of World War II, the family emigrated to Australia.[5]

Mesothelioma

editPaul Kraus received his Bachelor of Arts degree at Macquarie University and a Master of Arts and Education from the University of Sydney.[7] During a summer vacation as an undergraduate student, he worked adjacent to an asbestos factory, where he was exposed to fine asbestos dust.[8] Decades later, he was diagnosed with peritoneal mesothelioma, a cancer known to be caused by exposure from asbestos.[9] Due to his advanced metastases, doctors believed he only had weeks to live.[9]

Over the last 30 years, Kraus has worked as an author and educator.[9] He has written several books, including books co-written with Ian Gawler.[10]

Selected works

edit- Faith, Hope, Love and Laughter – How They Heal

- Not So Fabulous 50s: Images of a Migrant Childhood

- A New Australian, a New Australia

- Surviving Cancer: Inspirational Stories of Hope and Healing

- Prayers, Promises & Prescriptions for Healing

- Surviving Mesothelioma and Other Cancers: A Patient's Guide

- Mother Courage: From the Holocaust to Australia

References

edit- ^ a b Lewin, Natasha (8 May 2013). "Tales from a Survivor: An Interview with Author Paul Kraus". The Tolucan.

- ^ Baillie, Rebecca (24 May 2001). "Keeping fit helps man beat deadly cancer". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ Branley, Alison (7 May 2013). "Survivor sees his illness as a 'gift'". Herald News. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ Dinneem, Martin (29 March 2008). "Stories of Survival To Offer Inspiration". Newcastle Herald.

- ^ a b c d Brown, Malcolm (16 February 2011). "Mother who escaped SS with her infants". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ a b c Granski, Miki. "The Viehofen Forced-Labor Camp (1944-5)" (PDF). Mahnmal Viehofen. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ Kraus, Paul (2005). Surviving Mesothelioma and Other Cancers: A Patient's Guide. Raleigh, North Carolina: Cancer Monthly, LLC. ISBN 978-0-9772901-1-6.

- ^ Surviving Mesothelioma and Other Cancers: A Patient's Guide, p. 143

- ^ a b c Watson, Chad (7 June 2002). "Living Proof". Newcastle Herald. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ O’Connor, Michael (November 2012). "Prayers, Promises & Prescriptions". Aurora. 119 (22): 23. Retrieved 7 May 2013.