Paul Strand (October 16, 1890 – March 31, 1976) was an American photographer and filmmaker who, along with fellow modernist photographers like Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Weston, helped establish photography as an art form in the 20th century.[1][2] In 1936, he helped found the Photo League, a cooperative of photographers who banded together around a range of common social and creative causes. His diverse body of work, spanning six decades, covers numerous genres and subjects throughout the Americas, Europe, and Africa.

Paul Strand | |

|---|---|

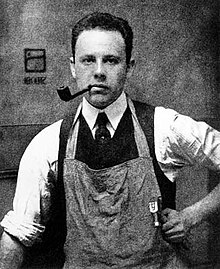

Paul Strand in a photograph by Alfred Stieglitz (1917) | |

| Born | Nathaniel Paul Stransky October 16, 1890 Brooklyn, New York, U.S. |

| Died | March 31, 1976 (aged 85) Orgeval, Yvelines, France |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Photography, filmmaking |

Background

editPaul Strand was born Nathaniel Paul Stransky on October 16, 1890, in New York; his Bohemian parents were merchant Jacob Stransky and Matilda Stransky (née Arnstein).[3] When Paul was 12, his father gave him a camera as a present.[4]

Career

editIn his late teens, he was a student of renowned documentary photographer Lewis Hine at the Ethical Culture Fieldston School. It was while on a field trip in this class that Strand first visited the 291 art gallery – operated by Stieglitz and Edward Steichen – where exhibitions of work by forward-thinking modernist photographers and painters would move Strand to take his photographic hobby more seriously. Stieglitz later promoted Strand's work in the 291 gallery itself, in his photography publication Camera Work, and in his artwork in the Hieninglatzing studio. Some of this early work, like the well-known Wall Street, experimented with formal abstractions (influencing, among others, Edward Hopper and his idiosyncratic urban vision).[5] Other of Strand's works reflect his interest in using the camera as a tool for social reform.[citation needed] When taking portraits, he would often mount a false brass lens to the side of his camera while photographing using a second working lens hidden under his arm. This meant that Strand's subjects likely had no idea he was taking their picture.[6] It was a move some criticized.

Photo League

editStrand was one of the founders of the Photo League, an association of photographers who advocated using their art to promote social and political causes. Strand and Elizabeth McCausland were "particularly active" in the League, with Strand serving as "something of an elder statesman." Both Strand and McCausland were "clearly left-leaning," with Strand "more than just sympathetic to Marxist ideas." Strand, McCausland, Ansel Adams, and Nancy Newhall all contributed to the League's publication, Photo News.[7]

Still photography and filmmaking

editOver the next few decades, Strand worked in motion pictures as well as still photography. His first film was Manhatta (1921), also known as New York the Magnificent, a silent film showing the day-to-day life of New York City made with painter/photographer Charles Sheeler.[8] Manhatta includes a shot similar to Strand's famous Wall Street (1915) photograph. In 1932–35, he lived in Mexico and worked on Redes (1936), a film commissioned by the Mexican government, released in the US as The Wave. Other films he was involved with were the documentary The Plow That Broke the Plains (1936) and the pro-union, anti-fascist Native Land (1942).

From 1933 to 1952, Strand had no darkroom of his own and used those of others.[9]

Communism

editIn December 1947, the Photo League appeared on the Attorney General's List of Subversive Organizations (AGLOSO).[9]

In 1948, CBS commissioned Strand to contribute a photo for an advertisement captured "It is Now Tomorrow": Strand's photo showed television antennas atop New York City.[10]

On January 17, 1949, Strand signed in support of Communist Party leaders (Benjamin J. Davis Jr., Eugene Dennis, William Z. Foster, John Gates, Gil Green (politician), Gus Hall, Irving Potash, Jack Stachel, Robert G. Thompson, John Williamson, Henry Winston, Carl Winter) in the Smith Act trials, along with Lester Cole, Martha Dodd, W.E.B. Dubois, Henry Pratt Fairchild, Howard Fast, Shirley Graham, Robert Gwathmey, E.Y. Harburg, Joseph H. Levy, Albert Maltz, Philip Morrison, Clarence Parker, Muriel Rukeyser, Alfred K. Stern (husband of Martha Dodd), Max Weber, and Henry Wilcox.[11]

Later years in Europe

editIn June 1949, Strand left the United States to present Native Land at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in Czechoslovakia. The remaining 27 years of his life were spent in Orgeval, France, where, despite never learning the language, he maintained an impressive, creative life, assisted by his third wife, fellow photographer Hazel Kingsbury Strand.[citation needed]

Although Strand is best known for his early abstractions, his return to still photography in this later period produced some of his most significant work in the form of six book "portraits" of place: Time in New England (1950), La France de Profil (1952), Un Paese (featuring photographs of Luzzara and the Po River Valley in Italy, Einaudi, 1955),[12] Tir a'Mhurain / Outer Hebrides[13][14] (1962), Living Egypt (1969, with James Aldridge) and Ghana: An African Portrait (with commentary by Basil Davidson; 1976).[citation needed]

Personal life

editStrand married the painter Rebecca Salsbury on January 21, 1922.[15] He photographed her frequently, sometimes in unusually intimate, closely cropped compositions. Following their divorce in 1933, Strand met Virginia Stevens and married her in 1936. They divorced in 1950. He married Hazel Kingsbury in 1951 and they remained married until his death in 1976."[16]

The timing of Strand's departure to France is coincident with the first libel trial of his friend Alger Hiss, with whom he maintained a correspondence until his death. Although he was never officially a member of the Communist Party, many of Strand's collaborators were either Party members (James Aldridge; Cesare Zavattini) or prominent left-leaning writers and activists (Basil Davidson). Many of his friends were also Communists or suspected of being so (Member of Parliament D. N. Pritt; film director Joseph Losey; Scottish poet Hugh MacDiarmid; actor Alex McCrindle). Strand was also closely involved with Frontier Films, one of more than 20 organizations that were identified as "subversive" and "un-American" by the US Attorney General. When he was asked by an interviewer why he decided to go to France, Strand began by noting that in America, at the time of his departure, "McCarthyism was becoming rife and poisoning the minds of an awful lot of people."[17]

During the 1950s, and owing to a printing process that was reportedly only available in that country at the time, Strand insisted that his books be printed in Leipzig, East Germany, even if it meant they were initially banned in the American market on account of their Communist provenance.[18] Following Strand's move to Europe, it was later revealed in de-classified intelligence files, obtained under the Freedom of Information Act and now preserved at the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona, that he was closely monitored by security services.[19]

Legacy

editIn 1984 Strand was posthumously inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum.[20]

The highest price reached by a Strand photograph in the art market was by Akeley Motion Picture Camera (1922), who sold by $783,750 at Christie's New York, on 4 April 2013.[21]

Publications

edit- Time in New England (1950)

- La France de Profil (1952)

- Un Paese (1955)[12]

- Tir a'Mhurain / Outer Hebrides (1962)[13]

- Living Egypt (1969), with James Aldridge

- Ghana: An African Portrait (1976), with commentary by Basil Davidson

Film

edit- Manhatta (1921; with Charles Sheeler), "considered to be the first American avant-garde film"[22]

Exhibitions

edit- Paul Strand: Photographs 1915–1945, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1945[23]

- Paul Strand: Photography and Film for the 20th Century, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2014;[24] Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 2016;[25][26][27][28] Fundación Mapfre, Madrid, 2020–21[29]

- Paul Strand: The Balance of Forces, Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris, 2023

Public collections

edit- The Art Institute of Chicago[30]

- The Cleveland Museum of Art[31]

- Dallas Museum of Art[32]

- J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles[33]

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art[34]

- Philadelphia Museum of Art[35]

- Princeton University Art Museum[36]

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York[37]

- Moderna Museet, Stockholm[38]

- Musée d'Orsay, Paris[39]

- Museum of Fine Arts, Houston[40]

- Museum of Modern Art, New York, 39 prints (as of 8 January 2022)[41]

- National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.[42]

- National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh[43]

- National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne[44]

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art[45]

- Saint Louis Art Museum[46]

- Smithsonian Museum of American Art, Washington, D.C.[47]

- Victoria and Albert Museum, London[48]

- Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 9 prints (as of 11 January 2022)[49]

References

edit- ^ AnOther (15 March 2016). "How Paul Strand Paved the Way For Photographic Modernism". AnOther. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ Dama, Francesco (28 June 2016). "An Intimate Encounter with Paul Strand's Photographic Journeys". Hyperallergic. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ "Philadelphia Museum of Art - Exhibitions - Paul Strand: Master of Modern Photography".

- ^ "Paul Strand". Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ Wells, Walter, Silent Theater: The Art of Edward Hopper, London/New York: Phaidon, 2007 ISBN 978-0-7148-4541-8

- ^ Conway, Richard (30 October 2014). "Paul Strand, Master of Modernism, in Retrospect". Time magazine. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Robinson, Gerald H. (2006). Photography, History & Science. Carl Mautz Publishing. pp. 38 (Photo League), 43 (documentarian), 91 (Realism), 111 (influence on Ansel Adams). ISBN 9781887694278. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ "Symphonies of steel and stone: silent cinema and the city". The Guardian. 21 March 2016. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ a b Strand, Paul (1987). Paul Strand. pp. 62 (dark room), 72 (AGLOSO). Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ Spigel, Lynn (2008). TV by Design: Modern Art and the Rise of Network Television. University of Chicago Press. pp. 68–69. ISBN 9780226769684. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ "Defense of arrested and indicted Communist leaders, 1948-49". House of Representatives Report No. 1700. US GPO. 1950. p. 46. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ a b "I posed for Paul Strand: the day the great photographer walked into my village in Italy". The Guardian. 16 March 2016. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ a b "Paul Strand's Hebrides: Subtle, sensitive with a dash of Marxist steel". The Guardian. 20 September 2012.

- ^ "Paul Strand's intimate and rich Hebridean images bought for Scottish gallery". The Guardian. 22 July 2015. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ New York, New York, Marriage Index 1866-1937

- ^ Buselle, Rebecca and Wilner-Stack, Trudy (2005). Paul Strand: Southwest (1st ed.). New York: Aperture. ISBN 9781931788465.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Adams, Robert, 1937- (1994). Why people photograph : selected essays and reviews (1st ed.). New York: Aperture. ISBN 0-89381-597-7. OCLC 31404331.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link), page 86 - ^ "Paul Strand and the Atlanticist Cold War" (PDF).

- ^ "Paul Strand: Master of Modern Photography".

- ^ "Paul Strand". International Photography Hall of Fame. Retrieved 2022-07-25.

- ^ Akeley Motion Picture Camera, New York, 1922, Christie's, 4 April 2013...

- ^ "Paul Strand, Charles Sheeler, Manhatta, 1921". MoMa.

- ^ "Paul Strand: Photographs 1915–1945". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ "Paul Strand's Sense of Things". The New Yorker. 15 April 2016. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ "Sean O'Hagan's top 10 photography exhibitions of 2016". the Guardian. 7 December 2016. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ "Photographic pioneer Paul Strand on show". BBC News. 18 March 2016. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ James Pickford, "V&A's Strand retrospective offers glimpse of lost world", The Financial Times, 15 March 2016.

- ^ "Paul Strand: Honest gaze of a craftsman's camera". Financial Times. 22 March 2016. Archived from the original on 2022-12-10. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ "Paul Strand exhibition in Barcelona". Fundación Mapfre. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ "Paul Strand". www.artic.edu. 1890. Retrieved 2022-05-11.

- ^ "Paul Strand". www.clevelandart.org. Retrieved 2022-05-11.

- ^ "Paul Strand". collections.dma.org. Retrieved 2022-05-11.

- ^ "Paul Strand". www.getty.edu. Retrieved 2022-05-11.

- ^ "Paul Strand". collections.lacma.org. Retrieved 2022-05-11.

- ^ "Paul Strand". www.philamuseum.org. Retrieved 2022-05-11.

- ^ "Paul Strand". artmuseum.princeton.edu. Retrieved 2022-05-11.

- ^ "Paul Strand (1890–1976)". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ "Paul Strand". sis.modernamuseet.se. Retrieved 2022-05-11.

- ^ "Paul Strand". www.musee-orsay.fr. Retrieved 2022-05-15.

- ^ "Paul Strand". emuseum.mfah.org. Retrieved 2022-05-15.

- ^ "Paul Strand". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 2022-01-08.

- ^ "Paul Strand". www.nga.gov. Retrieved 2022-05-15.

- ^ "Paul Strand". www.nationalgalleries.org. Retrieved 2022-05-15.

- ^ "Paul Strand". www.ngv.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2022-05-11.

- ^ "Paul Strand". www.sfmoma.org. Retrieved 2022-05-15.

- ^ "Paul Strand". www.slam.org. Retrieved 2022-05-11.

- ^ "Paul Strand". americanart.si.edu. Retrieved 2022-05-15.

- ^ "Search Results". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ "Paul Strand". whitney.org. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

Further reading

edit- Barberie, Peter. Paul Strand: Aperture Masters of Photography. Hong Kong: Aperture. ISBN 0-89381-077-0.

- Barberie, Peter and Bock Amanda N., ed. “Paul Strand: Master of Modern Photography.” Yale University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0300207927.

- Gualtieri, Elena. Paul Strand Cesare Zavattini: Lettere e immagini, Bologna, Bora, 2005. ISBN 88-88600-37-X.

- Hambourg, Maria Morris, Paul Strand circa 1916, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998 (available for download)

- MacDonald, Fraser. "Paul Strand and the Atlanticist Cold War" History of Photography 28.4 (2004), 356–373.

- Rosenblum, Naomi. A World History of Photography (3rd ed.). New York: Abbeville Press. ISBN 0-7892-0028-7.

- Stange, Maren. Paul Strand: essays on his life and work, New York: Aperture 1991.

- Weaver, Mike, "Paul Strand: Native Land", The Archive 27 (Tucson, Arizona: Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, 1990), 5–15.

External links

edit- Library of Congress: Paul Strand

- Paul Strand at MOMA

- Karen Rosenberg, "Expatriate Humanist, Lens Up His Sleeve, Paul Strand's Lifetime of Photography, at Philadelphia Museum" – The New York Times

- Zachary Rosen, "The photographer Paul Strand's 1960's Portrait of Ghana" – Africa is a Country

- Paul Strand at IMDb

- Paul Strand, Lumiere Gallery

- Paul Strand, Photographs of the American Southwest and Mexico. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.