Percy Green II, born in the Compton Hill neighborhood of St. Louis, is a social worker and Black activist in St. Louis, Missouri. He was active in the St. Louis chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and was a founding member of ACTION (Action Committee to Improve Opportunities for Negroes). He was also the plaintiff in the landmark civil rights case McDonnell Douglas Corp v. Green, which remains among the most frequently cited cases in American jurisprudence. Green has fought for equality and black inclusion in the St. Louis region for nearly half a century. He is a member of the Peace Economy Project's board.

Percy Green | |

|---|---|

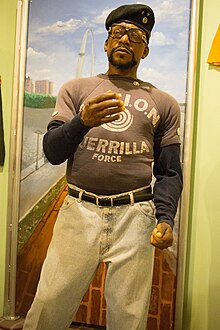

Wax Figure of Percy Green at the Griot Museum of Black History | |

| Born | 1935 (age 88–89) St. Louis, Missouri |

| Occupation(s) | Engineer, Trade Unionist, Activist |

| Known for | McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green |

Education

editGreen was educated at Toussaint L'Ouverture Elementary School, Vashon High School, and Washington University, from which he holds a master of social work.

Activism

editGreen has been involved in several landmark actions related to Civil Rights. The most famous of these took place in St. Louis; the first involved the construction of the St. Louis Gateway Arch and the second involved the Veiled Prophet Ball.

Gateway Arch

editOn July 14, 1964, Green and Richard Daly, a white college student, scaled the Gateway Arch to protest the exclusion of blacks from federal contracts and jobs related to the construction of the Arch.[1] Green, Daly, and protesters on the ground demanded that MacDonald Construction Company, the contractor responsible for constructing the Arch, raise the number of African Americans employed on the project to 10% within 10 days. Green and Daly were charged with trespassing and other offenses.[2] Today, a photo of Percy Green hangs inside the Arch in a display commemorating the Arch's history.[1] This incident was one of several that inspired the United States Department of Justice to file the first pattern or practice case against AFL–CIO under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[3]

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green

editLess than two months after climbing the Arch, Green was laid off by McDonnell Douglas Corporation, where he was employed as a mechanic and laboratory technician.[4] McDonnell Douglas claimed that the layoff was caused by budget constraints, but Green alleged that he was fired because of his race. The case was ultimately decided in Green's favor in the Supreme Court, in a landmark decision that clarified discrimination law by establishing the McDonnell Douglas burden-shifting framework. The fight for equal access to employment opportunities for African Americans characterized much of Green's work with both CORE and ACTION. His activism targeted companies including Wonder Bread, Southwestern Bell, Laclede Gas Company, and Union Electric (now Ameren UE).

Veiled Prophet Ball

editAlong with other members of ACTION, Green was involved in one of the city of St. Louis's most famous civil rights actions: a protest against the Veiled Prophet Ball. The Veiled Prophet Ball was an annual dance that had been held in December every year since 1878. The exclusivity of the ball was part of its appeal to St. Louis elite, but also the cause of different protests over many decades. By the 1960s, the ball—from which membership both Jews and African Americans were denied entry—was the target of Civil Rights protests led by ACTION and others. In December 1972, with the cooperation of several sympathetic debutantes, ACTION infiltrated the Veiled Prophet Ball and unmasked its symbolic head, the mysteriously hooded "Veiled Prophet." Once inside, ACTION member Jane Sauer created a distraction by dropping pamphlets near the stage while fellow member Gina Scott maneuvered behind the "Prophet" and snatched the hood from his head. Multiple witnesses confirmed that the Veiled Prophet was John K. Smith, a Vice President at Monsanto Corporation. "We thought that [the organization] was racist, sexist & elitist," Green later said. "If the city was going to truly integrate, they should not have a Ku Klux Klan-ish event. That’s why we attacked it." ACTION disbanded in 1985.[citation needed]

In response to Ellie Kemper's statement about her participation in the VP Ball, Green emphasized the need for elite institutions such as the VP Ball to be abolished, rather than simply diversified.[5]

St. Louis City

editGreen was subsequently hired to direct the minority and women-owned business utilization program. Under the administration of Mayor Freeman Bosley, Jr., Green oversaw the certification process and used that oversight to make sure certifications were not given to "front" businesses (where a woman or minority poses as the owner of a business that is actually run by a white man). He was retained in that position by the administration of Mayor Clarence Harmon, but his role was reduced to certification. Green was terminated by incoming Mayor Francis Slay in 2001.

CORE

editThe Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) was a national African American civil rights organization that aimed to resist segregation through nonviolent tactics.[6] The St. Louis Chapter of CORE was founded in 1947 and began as a biracial organization, consisting of students, educators, lawyers, and even some veterans of World War II.[7] Percy Green was a member of CORE until 1964 when he and 24 other members separated from the organization because they wanted to continue direct action protests.[8] This separation occurred due to disputes regarding tactics used to protest, specifically whether to continue using civil disobedience or to employ new direct action tactics.[7][9]

ACTION (1964 -1984)

editPercy Green was a founding member of ACTION (Action Committee to Improve Opportunities for Negroes).[10] The organization was first established in 1964 and continued activity through 1984.[7] ACTION focused on advocating and working for increased access to jobs offering higher pay for African Americans.[10] They targeted companies like Laclede Gas, Union Electric and Southwestern Bell, now known as Spire, Ameren, and AT&T, respectively.[8]

Other Notable Activism

editIn 1969, Percy Green and ACTION identified churches that had financial ties with St. Louis utility companies recognized by ACTION for having racist hiring practices. ACTION used black paint to "blackwash" several white statues of saints and religious figures to send a message.[11]

In the summer of 1970, Green and members of ACTION entered Southwestern Bell's headquarters equipped with molasses. The group poured the molasses in the lobby of the headquarters to stage a "stick-in", sending the message that the group would stick with the company until they changed their racist practices.[11]

References

edit- ^ a b Rivas, Rebecca S. (Feb 17, 2011). "Percy Green II recalls his historic 1964 protest with Richard Daly". St. Louis American.

- ^ Daly, Clarence (2004). "Between Civil Rights and Black Power in the Gateway City". Journal of Social History. doi:10.1353/jsh.2004.0013. S2CID 143641956.

- ^ Wright, John Allen (2002). Discovering African American St. Louis: A Guide to Historic Sites. Missouri History Museum. ISBN 1-883982-45-6.

- ^ McDonnell Douglas v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, at 794.

- ^ Green II, Percy (2021-06-09). "I helped infiltrate the Veiled Prophet Ball. Ellie Kemper's apology isn't enough". The Independent. Retrieved 2022-03-08.

- ^ "St. Louis CORE campaign for lunch counter desegregation, 1948-52 | Global Nonviolent Action Database". nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu. Retrieved 2023-11-15.

- ^ a b c Lang, Clarence (2004). "Between Civil Rights and Black Power in the Gateway City: The Action Committee to Improve Opportunities for Negroes (Action), 1964-75". Journal of Social History. 37 (3): 725–754. ISSN 0022-4529.

- ^ a b Krohe, Burk (2020-03-02). "Percy Green talks civil rights, protesting during annual 'Black in St. Louis'". UMSL Daily. Retrieved 2023-10-13.

- ^ "Monumental protest: Activist Percy Green's battle for fair hiring at the Arch". STLPR. Retrieved 2023-11-15.

- ^ a b "St. Louis Historic Preservation". dynamic.stlouis-mo.gov. Retrieved 2023-10-13.

- ^ a b O'Shea, Devin Thomas (2021-12-21). "The Prophet's Bane". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Retrieved 2023-11-15.