This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2020) |

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) is one of two components that make up the nervous system of bilateral animals, with the other part being the central nervous system (CNS). The PNS consists of nerves and ganglia, which lie outside the brain and the spinal cord.[1] The main function of the PNS is to connect the CNS to the limbs and organs, essentially serving as a relay between the brain and spinal cord and the rest of the body.[2] Unlike the CNS, the PNS is not protected by the vertebral column and skull, or by the blood–brain barrier, which leaves it exposed to toxins.[3]

| Peripheral nervous system | |

|---|---|

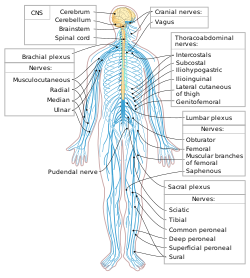

The human nervous system. Sky blue is PNS; yellow is CNS. | |

| Identifiers | |

| Acronym(s) | PNS |

| MeSH | D017933 |

| TA98 | A14.2.00.001 |

| TA2 | 6129 |

| FMA | 9093 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The peripheral nervous system can be divided into the somatic nervous system and the visceral nervous system. Each of these have a sensory and a motor division. The visceral motor division is known as the autonomic nervous system.[4] In the somatic nervous system, the cranial nerves are part of the PNS with the exceptions of the olfactory nerve and epithelia and the optic nerve (cranial nerve II) along with the retina, which are considered parts of the central nervous system based on developmental origin. The second cranial nerve is not a true peripheral nerve but a tract of the diencephalon.[5] Cranial nerve ganglia, as with all ganglia, are part of the PNS.[6] The autonomic nervous system exerts involuntary control over smooth muscle and glands.[7] The connection between CNS and organs allows the system to be in two different functional states: sympathetic and parasympathetic.

Structure

editThe peripheral nervous system is divided into the somatic nervous system, and the autonomic nervous system. The somatic nervous system is under voluntary control, and transmits signals from the brain to end organs such as muscles. The sensory nervous system is part of the somatic nervous system and transmits signals from senses such as taste and touch (including fine touch and gross touch) to the spinal cord and brain. The autonomic nervous system is a "self-regulating" system which influences the function of organs outside voluntary control, such as the heart rate, or the functions of the digestive system.

Somatic nervous system

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2020) |

The somatic nervous system includes the sensory nervous system (ex. the somatosensory system) and consists of sensory nerves and somatic nerves, and many nerves which hold both functions.

In the head and neck, cranial nerves carry somatosensory data. There are twelve cranial nerves, ten of which originate from the brainstem, and mainly control the functions of the anatomic structures of the head with some exceptions. One unique cranial nerve is the vagus nerve, which receives sensory information from organs in the thorax and abdomen. The other unique cranial nerve is the accessory nerve which is responsible for innervating the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles, neither of which are located exclusively in the head.

For the rest of the body, spinal nerves are responsible for somatosensory information. These arise from the spinal cord. Usually these arise as a web ("plexus") of interconnected nerves roots that arrange to form single nerves. These nerves control the functions of the rest of the body. In humans, there are 31 pairs of spinal nerves: 8 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar, 5 sacral, and 1 coccygeal. These nerve roots are named according to the spinal vertebrata which they are adjacent to. In the cervical region, the spinal nerve roots come out above the corresponding vertebrae (i.e., nerve root between the skull and 1st cervical vertebrae is called spinal nerve C1). From the thoracic region to the coccygeal region, the spinal nerve roots come out below the corresponding vertebrae. This method creates a problem when naming the spinal nerve root between C7 and T1 (so it is called spinal nerve root C8). In the lumbar and sacral region, the spinal nerve roots travel within the dural sac and they travel below the level of L2 as the cauda equina.

Cervical spinal nerves (C1–C4)

editThe first 4 cervical spinal nerves, C1 through C4, split and recombine to produce a variety of nerves that serve the neck and back of head.

Spinal nerve C1 is called the suboccipital nerve, which provides motor innervation to muscles at the base of the skull. C2 and C3 form many of the nerves of the neck, providing both sensory and motor control. These include the greater occipital nerve, which provides sensation to the back of the head, the lesser occipital nerve, which provides sensation to the area behind the ears, the greater auricular nerve and the lesser auricular nerve.

The phrenic nerve is a nerve essential for our survival which arises from nerve roots C3, C4 and C5. It supplies the thoracic diaphragm, enabling breathing. If the spinal cord is transected above C3, then spontaneous breathing is not possible.[citation needed]

Brachial plexus (C5–T1)

editThe last four cervical spinal nerves, C5 through C8, and the first thoracic spinal nerve, T1, combine to form the brachial plexus, or plexus brachialis, a tangled array of nerves, splitting, combining and recombining, to form the nerves that subserve the upper-limb and upper back. Although the brachial plexus may appear tangled, it is highly organized and predictable, with little variation between people. See brachial plexus injuries.

Lumbosacral plexus (L1–Co1)

editThe anterior divisions of the lumbar nerves, sacral nerves, and coccygeal nerve form the lumbosacral plexus, the first lumbar nerve being frequently joined by a branch from the twelfth thoracic. For descriptive purposes this plexus is usually divided into three parts:

Autonomic nervous system

editThe autonomic nervous system (ANS) controls involuntary responses to regulate physiological functions.[8] The brain and spinal cord of the central nervous system are connected with organs that have smooth muscle, such as the heart, bladder, and other cardiac, exocrine, and endocrine related organs, by ganglionic neurons.[8] The most notable physiological effects from autonomic activity are pupil constriction and dilation, and salivation of saliva.[8] The autonomic nervous system is always activated, but is either in the sympathetic or parasympathetic state.[8] Depending on the situation, one state can overshadow the other, resulting in a release of different kinds of neurotransmitters.[8]

Sympathetic nervous system

editThe sympathetic system is activated during a "fight or flight" situation in which mental stress or physical danger is encountered.[8] Neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine, and epinephrine are released,[8] which increases heart rate and blood flow in certain areas like muscle, while simultaneously decreasing activities of non-critical functions for survival, like digestion.[9] The systems are independent to each other, which allows activation of certain parts of the body, while others remain rested.[9]

Parasympathetic nervous system

editPrimarily using the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) as a mediator, the parasympathetic system allows the body to function in a "rest and digest" state.[9] Consequently, when the parasympathetic system dominates the body, there are increases in salivation and activities in digestion, while heart rate and other sympathetic response decrease.[9] Unlike the sympathetic system, humans have some voluntary controls in the parasympathetic system. The most prominent examples of this control are urination and defecation.[9]

Enteric nervous system

editThere is a lesser known division of the autonomic nervous system known as the enteric nervous system.[9] Located only around the digestive tract, this system allows for local control without input from the sympathetic or the parasympathetic branches, though it can still receive and respond to signals from the rest of the body.[9] The enteric system is responsible for various functions related to gastrointestinal system.[9]

Disease

editDiseases of the peripheral nervous system can be specific to one or more nerves, or affect the system as a whole.

Any peripheral nerve or nerve root can be damaged, called a mononeuropathy. Such injuries can be because of injury or trauma, or compression. Compression of nerves can occur because of a tumour mass or injury. Alternatively, if a nerve is in an area with a fixed size it may be trapped if the other components increase in size, such as carpal tunnel syndrome and tarsal tunnel syndrome. Common symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome include pain and numbness in the thumb, index and middle finger. In peripheral neuropathy, the function one or more nerves are damaged through a variety of means. Toxic damage may occur because of diabetes (diabetic neuropathy), alcohol, heavy metals or other toxins; some infections; autoimmune and inflammatory conditions such as amyloidosis and sarcoidosis.[8] Peripheral neuropathy is associated with a sensory loss in a "glove and stocking" distribution that begins at the peripheral and slowly progresses upwards, and may also be associated with acute and chronic pain. Peripheral neuropathy is not just limited to the somatosensory nerves, but the autonomic nervous system too (autonomic neuropathy).[8]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Alberts, Daniel (2012). Dorland's illustrated medical dictionary (32nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 1862. ISBN 9781416062578.

- ^ "Slide show: How your brain works - Mayo Clinic". mayoclinic.com. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ Aspromonte, John (2019). ADHD : the ultimate teen guide. Lanham. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-5381-0039-4. OCLC 1048014796.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Saladin, Kenneth (2024). Anatomy & Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function (10th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill. p. 1076. ISBN 9781266041846.

- ^ Board Review Series: Neuroanatomy, 4th Ed., Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Maryland 2008, p. 177. ISBN 978-0-7817-7245-7.

- ^ James S. White (21 March 2008). Neurobioscitifity. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-07-149623-0. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ^ Campbell biology. Lisa A. Urry, Michael L. Cain, Steven Alexander Wasserman, Peter V. Minorsky, Rebecca B. Orr, Neil A. Campbell (12th ed.). New York, NY. 2021. ISBN 978-0-13-518874-3. OCLC 1119065904.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Laight, David (September 2013). "Overview of peripheral nervous system pharmacology". Nurse Prescribing. 11 (9): 448–454. doi:10.12968/npre.2013.11.9.448. ISSN 1479-9189.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Matic, Agnella Izzo (2014). "Introduction to the Nervous System, Part 2: The Autonomic Nervous System and the Central Nervous System". AMWA Journal: American Medical Writers Association Journal (AMWA J). ISSN 1075-6361.[permanent dead link]

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2007) |

External links

edit- Peripheral nervous system photomicrographs

- Peripheral Neuropathy Archived 2016-12-15 at the Wayback Machine from the US NIH

- Neuropathy: Causes, Symptoms and Treatments from Medical News Today

- Peripheral Neuropathy at the Mayo Clinic