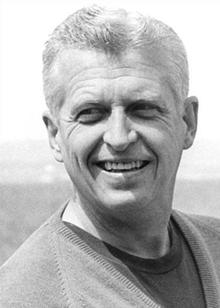

Philip Francis Berrigan SSJ (October 5, 1923 – December 6, 2002) was an American peace activist and Catholic priest[1][2][3] with the Josephites.[4][5] He engaged in nonviolent, civil disobedience in the cause of peace and nuclear disarmament and was often arrested.[6][7]

Philip Berrigan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Philip Francis Berrigan October 5, 1923 Two Harbors, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Died | December 6, 2002 (aged 79) Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

| Burial place | St. Peter the Apostle Cemetery |

| Education | |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3 |

| Relatives | Daniel Berrigan (brother) |

In 1973, he married a former nun, Elizabeth McAlister. Both were subsequently excommunicated by the Catholic Church before being reinstated. For eleven years of their 29-year marriage they were separated by one or both serving time in prison.[8][6]

Biography

editEarly life and education

editBerrigan was born in Two Harbors, Minnesota, a Midwestern, working-class town. He had five brothers, including the Jesuit fellow-activist and poet, Daniel Berrigan. His mother, Frieda (née Fromhart), was of German descent and deeply religious. His father, Tom Berrigan, was a second-generation Irish-Catholic, trade union member, socialist, and railway engineer.[4][6]

Philip Berrigan graduated from high school in Syracuse, New York, and was then employed cleaning trains for the New York Central Railroad. He played with a semi-professional baseball team. In 1943, after a semester of schooling at St. Michael's College, Toronto, Berrigan was drafted into combat duty in World War II. He served in the artillery during the Battle of the Bulge (1945) and later became a Second Lieutenant in the infantry.[4] He was deeply affected by racial segregation and racism during boot camp in the American South.[9][10] Berrigan graduated with an English degree from the College of the Holy Cross, a Jesuit college in Worcester, Massachusetts.

Josephites and early priesthood

editIn 1950, he joined the Society of St. Joseph of the Sacred Heart, better known as the Josephites, a religious society of priests and lay brothers dedicated to serving African-Americans (who were still dealing with the repercussions of slavery and daily segregation in the United States). After studying at the theological school of the Society, St. Joseph's Seminary in Washington, D.C., he was ordained a priest in 1955.

He went on to gain a degree in Secondary Education at Loyola University of the South (1957) and then a Master of Arts degree at Xavier University of Louisiana in 1960, during which time he began to teach at St. Augustine High.[4]

In addition to his academic responsibilities, Berrigan became active in the Civil Rights Movement. He marched for desegregation and participated in sit-ins and bus boycotts. His brother Daniel wrote of him:

From the beginning, he stood with the urban poor. He rejected the traditional, isolated stance of the Church in black communities. He was also incurably secular; he saw the Church as one resource, bringing to bear on the squalid facts of racism the light of the Gospel, the presence of inventive courage and hope.[4]

Berrigan was first imprisoned in 1962/1963. During his many prison sentences, he would often hold Bible study class and offer legal educational support to other inmates. As a priest, his activism and arrests met with deep disapproval from the leadership of the Catholic Church and Berrigan was moved to Epiphany Apostolic College, the Josephite minor seminary in Newburgh, New York, but he continued his protests. Working with Jim Forest, in 1964 he founded the Catholic Peace Fellowship in New York City. He was moved again to St. Peter Claver Parish in West Baltimore, Maryland, from where he started the Baltimore Interfaith Peace Mission, leading lobbies and demonstrations.[4]

Protests

editBaltimore Four

editBerrigan and others took increasingly radical steps to bring attention to the anti-war movement. The group, later known as the Baltimore Four occupied the Selective Service Board in the Customs House, Baltimore, on October 27, 1967.[11] 'The Four' were Berrigan, artist Tom Lewis, writer David Eberhardt, and the Rev. James L. Mengel III. Mengel was a United States Air Force veteran and a United Church of Christ pastor. Performing a sacrificial, blood-pouring protest, they used their own blood and that from poultry and poured it over selective service (draft) records.[11][12] During their trial Mengel stated that U.S. military forces had killed and maimed not only humans, but also animals and vegetation. Mengel agreed to the action and donated blood, but decided not to actually pour blood. Instead he distributed the paperback book version of the New Testament to draft board workers, newsmen, and police.[5][11] Berrigan, in a written statement, noted that his sacrificial and constructive act was meant to protest "the pitiful waste of American and Vietnamese blood in Indochina".[4]

The trial of the four defendants was postponed due to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and the subsequent riots in Baltimore and other U.S. cities. Eberhardt and Lewis served jail time and Berrigan was sentenced to six years in federal prisons.[13][7][8]

Catonsville Nine

editIn 1968, six months after the Baltimore draft records protest, while out on bail, Berrigan decided to repeat the protest in a modified form. A high school physics teacher, Dean Pappas, helped to concoct homemade napalm. Nine activists, including Berrigan's Jesuit brother Daniel, later became known as the Catonsville Nine when they walked into the offices of the local draft board in Catonsville, Maryland, removed 600 draft records, doused them in napalm and burnt them in a lot outside of the building.[11][14] The Catonsville Nine, who were all Catholics, issued a statement:

We confront the Roman Catholic Church, other Christian bodies, and the synagogues of America with their silence and cowardice in the face of our country's crimes. We are convinced that the religious bureaucracy in this country is racist, is an accomplice in this war, and is hostile to the poor.[11][14]

Berrigan was convicted of conspiracy and destruction of government property on November 8, 1968, but was bailed for 16 months while the case went to the U.S. Supreme Court. The court rejected the appeal and Berrigan and three others went into hiding. For a time, Liz McAlister, the nun who would later become his wife, helped hide Berrigan in New Jersey.[15] Twelve days later Berrigan was arrested by the FBI and jailed in Lewisburg.[4][6] All nine were sentenced to three years in prison.[11][14][16]

The Harrisburg Seven

editBerrigan attracted the notice of federal authorities again when he and six other anti-war activists were caught trading letters alluding to kidnapping Henry Kissinger and bombing steam tunnels.[17] They were charged with 23 counts of conspiracy including plans for kidnap and blowing up heating tunnels in Washington.[4] The government spent $2 million on the 1972 Harrisburg Seven trial but did not win a conviction.[18] This was one of the reversals suffered by the U.S. government in such cases, another being The Camden 28 in 1973.

Other actions

editBerrigan organized or inspired many additional operations. The D.C. Nine, in March 1969, consisted of mostly priests and nuns disrupting the Washington Dow Chemical offices by scattering their files.[19] The group protested Dow's production of napalm for use in the Vietnam War. The D.C. Nine were later tried in Washington, D.C., but an appeal was won in their favor. Some jail time was served.[20] Later in May 1969, the Chicago 15 Catholics protested napalm and burned 40,000 draft cards.[19]

He helped the Milwaukee 14 in a protest against the Milwaukee Draft Boards on September 24, 1968. The Fourteen men burned 10,000 1-A draft files. After being arrested, they spent a month in prison, unable to raise bail set at $415,000. Father James Groppi came to their aid, co-chairing the Milwaukee 14 Defense Committee. Members were later placed on trial and many did considerable jail time.[21]

He supported the Citizens' Commission to Investigate the FBI, the burglary of an FBI field office in Media, Penn., to expose the methods of J. Edgar Hoover against war protesters.[22]

He was also involved with the Camden 28, who took action against the Camden, New Jersey, draft board. The group was arrested and the trial resulted in acquittal on all charges. A book has been written about this action by Ed McGowan and a documentary made by Giacchino, which appeared on PBS TV.[23]

Berrigan likewise supported the Harrisburg Seven, whose plan was to put people in the government like Henry Kissinger under citizens arrest for the waging of an illegal war. Philip Berrigan and others were arrested for conspiracy. They had only gathered together to discuss the idea.[24]

In 1968, Berrigan signed the Writers and Editors War Tax Protest pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War.[25][26]

Marriage

editBerrigan, while still a priest, married former nun Elizabeth McAlister in 1969 by mutual consent.[6] In 1973, they legalized their marriage, and were subsequently excommunicated by the Catholic Church, though their excommunication was later lifted.[27] Together they founded Jonah House in Baltimore, a community to support resistance to war.

Plowshares Movement

editOn September 9, 1980, Berrigan, his brother Daniel, with Sister Anne Montgomery, Elmer H. Maas, Rev. Carl Kabat, O.M.I., John Schuchardt, Dean Hammer and Molly Rush[28] known as the Plowshares Eight entered the General Electric Re-entry Division[29] in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, where Mark 12A reentry vehicles[30] for the Minuteman III Intercontinental Ballistic missiles (ICBMs) were made. They hammered on two reentry vehicles, poured blood on documents, and offered prayers for peace. This is considered the beginning of the Plowshares Movement. They were arrested and charged with ten different felony and misdemeanor counts.[31] On April 10, 1990, after nearly ten years of trials and appeals, the Plowshares Eight were re-sentenced and paroled for up to 23 months in consideration of time already served in prison. Berrigan helped set up Jonah House as the community headquarters of the organisation, a terraced house in Reservoir Hill, Baltimore. The headquarters later was moved to St. Peter the Apostle Cemetery in West Baltimore.[6][11]

Berrigan's last Plowshares action occurred in December 1999, when a group of protesters hammered on A-10 Warthog warplanes held at the Warfield Air National Guard Base. He was indicted for malicious destruction of property and sentenced to 30 months in prison.[4][7] He was released on December 14, 2001. In his lifetime he had spent about 11 years in jails and prisons for civil disobedience.[4][32]

In one of his last public statements, Berrigan said,

The American people are, more and more, making their voices heard against Bush and his warrior clones. Bush and his minions slip out of control, determined to go to war, determined to go it alone, determined to endanger the Palestinians further, determined to control Iraqi oil, determined to ravage further a suffering people and their shattered society. The American people can stop Bush, can yank his feet closer to the fire, can banish the war makers from Washington D.C., can turn this society around and restore it to faith and sanity.[5]

Death

editOn December 6, 2002, Philip Berrigan died of liver and kidney cancer at the age of 79 at Jonah House in Baltimore.[4] In a last statement, he said

I die with the conviction, held since 1968 and Catonsville, that nuclear weapons are the scourge of the earth; to mine for them, manufacture them, deploy them, use them, is a curse against God, the human family, and the earth itself.[4]

Howard Zinn, professor emeritus at Boston University, paid this tribute to Berrigan saying: "Mr. Berrigan was one of the great Americans of our time. He believed war didn't solve anything. He went to prison again and again and again for his beliefs. I admired him for the sacrifices he made. He was an inspiration to a large number of people."[4]

The funeral was held at St. Peter Claver Church in West Baltimore and he was buried in West Baltimore cemetery. Berrigan's widow, Elizabeth McAlister, and others still maintain Jonah House in Baltimore and a website that details all Plowshares activities.[4][33] His four brothers, Daniel, John, Jim, and Jerome; his wife, Elizabeth McAlister; and their three children, Frida, Jerry, and Kate, are or were all also activists in the peace movement.[4]

Personal life

editWith his wife Liz he had three children: Frida (b. 1974), Jerry (b. 1975), and Kate (b. 1981).[4][8][6]

Works

edit- No More Strangers, Punishment for Peace ISBN 0-345-22430-2

- Prison Journals of a Priest Revolutionary ISBN 0-03-084513-0

- Punishment for Peace ISBN 0-345-02430-3

- Disciples and Dissidents, 2000 Haley's, edited by Fred Wilcox, authors Steven Baggarly, Philip Berrigan, Mark Coville, Susan Crane, Steve Kelly, S.J.. Tom Lewis-Borbely[34]

- Widen the Prison Gates ISBN 0-671-21638-4

- Fighting the Lamb's War, 1996 (autobiography) ISBN 1-56751-101-5

- The Times' Discipline, written with his wife about Jonah House

- A Ministry of Risk: Writings on Peace and Nonviolence, 2024 edited by Brad Wolf ISBN 978-1-5315-0628-5

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Lewis, Daniel (December 8, 2002). "Philip Berrigan, Former Priest and Peace Advocate in the Vietnam War Era, Dies at 79". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 19, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ "Obituary: Philip Berrigan". the Guardian. December 12, 2002. Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ "Remembering Jesuit Priest And Anti-War Activist Daniel Berrigan". NPR.org. Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Kelly, Jacques; Schoettler, Carl (December 7, 2002). "Philip Berrigan, apostle of peace, dies at age 79". Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on October 19, 2017. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ^ a b c Nepstad, Sharon Erickson (2008). Religion and war resistance in the Plowshares Movement. Cambridge University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-521-71767-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g Berrigan, Frida (2015). It Runs in the Family: On Being Raised by Radicals and Growing into Rebellious Motherhood. OR Books. ISBN 978-1-5318-2610-9. OCLC 947798459.

- ^ a b c Gay, Kathlyn (2011). American dissidents: An encyclopedia of activists, subversives, and prisoners of conscience. ABC-CLIO. p. 66. ISBN 9781598847659.

- ^ a b c "Philip Berrigan and Elizabeth McAlister papers, DePaul University Special Collections and Archives". DePaul University Libraries. Archived from the original on February 6, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ Lombardi, Chris (2020). I Ain't Marching Anymore: Dissenters, Deserters, and Objectors to America's Wars. The New Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-62097-318-9.

- ^ Shearer, Benjamin F., ed. (2006). Home Front Heroes. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-313-04705-3. Archived from the original on December 27, 2021. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

Boot camp in the South made him a civil rights activist.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nepstad, Sharon Erickson (2008). Religion and war resistance in the Plowshares Movement. Cambridge University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780521717670.

- ^ Strabala; Palecek (2002). Prophets without honor: a requiem for moral patriotism. Algora Publishing. pp. 57–61. ISBN 978-1892941992.

- ^ United States v. Eberhardt, 417 F.2d 1009 (4th Cir. 1969).

- ^ a b c Peters, Shawn Francis (2012). The Catonsville Nine: A Story of Faith and Resistance in the Vietnam Era. Oxford University Press. p. 35. ISBN 9780199942756.

- ^ Peters, Shawn Francis (2012). The Catonsville Nine. New York City: Oxford University Press. pp. 272. ISBN 978-0199827855.

- ^ United States v. Moylan, 417 F.2d 1002 (4th Cir. 1969).

- ^ "No again on the conspiracy law". Time. Vol. 99, no. 16. April 17, 1972. ISSN 0040-781X. EBSCOhost 53809591. Archived from the original on October 28, 2010. Retrieved September 8, 2007.

- ^ Schmidt, Jeff (2001). Disciplined Minds: A Critical Look at Salaried Professionals and the Soul-battering System that Shapes Their Lives. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-7425-1685-4. Archived from the original on December 27, 2021. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ^ a b Nobile, Philip (June 28, 1970). "The Priest Who Stayed Out in the Cold". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 5, 2017.

- ^ The Catonsville Nine: A Story of Faith and Resistance in the Vietnam Era (2012) Shawn Francis Peters, Oxford University Press, p. 246 ISBN 9780199942756

- ^ The Catonsville Nine: A Story of Faith and Resistance in the Vietnam Era (2012) Shawn Francis Peters, Oxford University Press, p. 157 ISBN 9780199942756

- ^ Medsger, Betty (2014). The Burglary: The Discovery of J. Edgar Hoover's Secret F.B.I.. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-96295-9.

- ^ Kairys, D. (2009). Philadelphia freedom: Memoir of a civil rights lawyer. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472021369.

- ^ Berger, Dan, ed. (2010). The hidden 1970s: Histories of radicalism. Rutgers University Press. p. 261. ISBN 9780813548746.

- ^ Writers and Editors War Tax Protest, FBI, 1968, retrieved June 25, 2017

- ^ "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest Names". Brooklyn, NY: National War Tax Resistance Coordinating Committee. Archived from the original on October 19, 2017. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ^ O'Grady, Jim (November 23, 2016). "The passionate lives of Dan and Phil Berrigan". America Magazine. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- ^ Norman, Liane Ellison (2016). Hammer of Justice : Molly Rush and the plowshares eight. WIPF & STOCK Publishers. ISBN 978-1532607646. OCLC 959034499.

- ^ Paige, Hilliard W. "GE Re-entry systems, Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM)" (PDF). American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 1, 2020. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- ^ "The W-78 Warhead, Intermediate yield strategic ICBM MIRV". nuclearweaponarchive.org. September 1, 2001. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- ^ Commonwealth v. Berrigan, 501 A.2d 226 (Pa. 118 1985).

- ^ Watson, Patrica (December 2002 – January 2003). "From the editor's desk". Peacework Magazine. American Friends Service Committee. Archived from the original on October 11, 2006.

- ^ Pietila, Antero (June 14, 2004). "Resurrecting a cemetery, demonstrating for peace". Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on October 19, 2017. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ^ Disciples & dissidents : prison writings of the Prince of Peace Plowshares. Baggarly, Stephen, 1965–, Wilcox, Fred A. (Fred Allen), Prince of Peace Plowshares (Group). Athol, MA: Haley's. 2001. ISBN 1884540422. OCLC 44634298.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

Further reading

edit- The Berrigan brothers: the story of Daniel and Philip Berrigan (1974) the University of Michigan

- Murray Polner and Jim O'Grady Disarmed and Dangerous: The Radical Lives & Times of Daniel & Philip Berrigan (Basic Books, 1997; Westvew Press, 1998)

- Jerry Elmer, Felon for Peace Vanderbilt University Press, 2005 ISBN 9780826514950

- Francine du Plessix Gray, Divine Disobedience: Profiles in Catholic Radicalism (Knopf, 1970)

- Daniel Cosacchi and Eric Martin, eds., The Berrigan Letters: Personal Correspondence between Daniel and Philip Berrigan (Orbis Books, 2016)

External links

edit- Philip Berrigan and Elizabeth McAlister papers, DePaul University Special Collections and Archives

- Murry Polner Papers, DePaul University Special Collections and Archives (notes and documents from writing Disarmed and Dangerous: The Radical Lives & Times of Daniel & Philip Berrigan)

- Archive of Philip Berrigan on Democracy Now!

- Jonah House website

- DVD on Philip & Daniel Berrigan and the story of the Catonsville Nine.

- Berrigan Brothers And The Harrisburg Seven Trial, 1970–1989 at the Internet Archive