Philip Jeck (15 November 1952 – 25 March 2022) was an English composer and multimedia artist. His compositions were noted for utilising antique turntables and vinyl records, along with looping devices and both analogue and digital effects.[3] Initially composing for installations and dance companies, beginning in 1995 he released music on the UK label Touch.

Philip Jeck | |

|---|---|

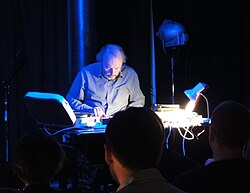

Jeck performing in 2011 | |

| Background information | |

| Born | 15 November 1952 |

| Origin | England |

| Died | 25 March 2022 (aged 69) |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments | |

| Years active | 1980s–2022 |

| Labels |

|

| Website | www |

Early life

editJeck was born in England in 1952.[6][3][7] He studied visual arts at Dartington College of Arts in Devon.[3][8] He became interested in record players after visiting New York in 1979 and being introduced to the work of DJs such as Walter Gibbons and Larry Levan.[9]

Career

editJeck started exploring composition using record players and electronics in the early 1980s. In his early career, he composed and performed scores for dance and theatre companies, including a five-year collaboration with Laurie Booth.[3] He also composed scores for dance films Beyond Zero on Channel 4 and Pace on BBC 2.[10][11] Jeck was perhaps best known for his 1993 work Vinyl Requiem with Lol Sargent, a performance for 180 Dansette record players, 12 slide-projectors and two film-projectors.[3] Although he initially intended to perform it only once, he went on to organise further performances of the installation.[7] It won the Time Out Performance Award in 1993.[3][12]

Jeck signed with Touch in 1995 and proceeded to release his best-known works on the label, including Surf (1998), Stoke (2002), and 7 (2003). In 2004, he collaborated with Alter Ego on a 2005 rendition of composer Gavin Bryars's The Sinking of the Titanic.[3] His 2008 album, Sand, was named the second best album of that year by The Wire.[13] Many of his studio releases are pieced together from recordings of his own live performances and stitched together with a MiniDisc recorder.[3] His final music credit came in 2021 with Stardust, a collaboration with Faith Coloccia.[14]

He collaborated with artists including Jah Wobble, Jaki Liebezeit, David Sylvian and Janek Schaefer.[3]

Death

editJeck died on 25 March 2022, aged 69, following a brief illness.[15][8][14]

Discography

editStudio and live recordings

edit- Loopholes (1995, Touch)[16]

- Surf (1998, Touch)[16]

- Live in Tokyo (2000, Touch)[16]

- Vinyl Coda I–III (2 CDs) (2000, Intermedium Records)[16]

- Vinyl Coda IV (2001, Intermedium Records)[16]

- Stoke (2002, Touch)[16][17]

- 7 (2003, Touch)[16][18]

- Sand (2008, Touch)[16][19]

- Suite. Live in Liverpool (2008, Touch)[16]

- An Ark for the Listener (2010, Touch)[16]

- Cardinal (2015, Touch)[16][19]

- Iklectik (2017, Touch)[16]

Collaborations

edit- Soaked with Jacob Kirkegaard (2002, Touch)[16]

- Live in Leuven with Jah Wobble and Jaki Liebezeit (2004, Hertz)[16][20]

- Songs for Europe with Janek Schaefer (2004, Asphodel)[16][21]

- The Sinking of the Titanic with Alter Ego and Gavin Bryars (2007, Touch)[20][19]

- Spliced with Marcus Davidson (2010, Touch)[16][20]

- Stardust with Faith Coloccia (2021, Touch)[16][20]

- Oxmardyke with Chris Watson (2023, Touch)[16][20]

References

edit- ^ Gotrich, Lars (10 September 2019). "Viking's Choice: What I Learned From Aquarius Records, A Record Store For Big Ears". NPR. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ Sherburne, Philip (28 March 2022). "10 Must-Hear Recordings by Experimental Turntablist Philip Jeck, Who Found Infinity in Vinyl's Grooves". Pitchfork. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bush, John. "Philip Jeck – Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ Clark, Philip (26 December 2015). "The playlist: best experimental music of 2015 – Laura Cannell, Philip Jeck and more". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ Albiez, Sean (2017). Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World, Volume 11. Bloomsbury. pp. 347–349. ISBN 978-1-5013-2610-3. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ Staff. "Philip Jeck – CV" Archived 28 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine. www.philipjeck.com.

- ^ a b Rutherford-Johnson, Tim (2017). Music After the Fall: Modern Composition and Culture Since 1989. University of California Press. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-520-28314-5.

- ^ a b Beaumont-Thomas, Ben (28 March 2022). "Philip Jeck, acclaimed British experimental composer, dies aged 69". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ Saunders, James. "Interview with Philip Jeck". The Ashgate Research Companion to Experimental Music. Ashgate. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Rowell, Bonnie (2000). Dance Umbrella: The First Twenty-one Years. Dance Books. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-85273-077-2.

- ^ "Pace". British Film Institute. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ Beaumont-Thomas, Ben (28 March 2022). "Philip Jeck, acclaimed British experimental composer, dies aged 69". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ "Biography". Philip Jeck official website. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ a b Minsker, Evan (27 March 2022). "Philip Jeck, Experimental Composer and Turntablist, Dies at 69". Pitchfork. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ Minsker, Evan (27 March 2022). "Philip Jeck, Experimental Composer and Turntablist, Dies at 69". Pitchfork. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Philip Jeck – Album Discography". AllMusic. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ Richardson, Mark (26 November 2002). "Stoke". Pitchfork. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ Richardson, Mark (13 January 2004). "7". Pitchfork. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ a b c Cornish, Dale (28 March 2022). "The Quietus | Features | Remember Them... | Remembering Philip Jeck". The Quietus. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Philip Jeck – Credits". AllMusic. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ Staff (21 October 2004). "Songs for Europe". Pitchfork. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

External links

edit- Official website

- Howard, Ed (1 September 2003). "Philip Jeck: Artist Profile". Stylus Magazine. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012.

- Philip Jeck discography at Discogs

- Philip Jeck at IMDb