Ponce (US: /ˈpɔːnseɪ, ˈpoʊn-/ PAWN-say, POHN-, UK: /ˈpɒn-/ PON-, Spanish: [ˈponse] ) is a city and a municipality on the southern coast of Puerto Rico.[25] The most populated city outside the San Juan metropolitan area, Ponce was founded on August 12, 1692[note 1][26][20][27][17] and is named after Juan Ponce de León y Loayza,[28] the great-grandson of Spanish conquistador Juan Ponce de León.[note 2] Ponce is often referred to as La Perla del Sur (The Pearl of the South), La Ciudad Señorial[b] (The Manorial City[c]), and La Ciudad de las Quenepas (Genip City).

Ponce

Municipio Autónomo de Ponce | |

|---|---|

City and municipality | |

| Autonomous Municipality of Ponce | |

| Nicknames: "La Perla del Sur", "Ciudad Señorial", "Ciudad de los Leones", "Ciudad de las Quenepas" | |

| Motto: | |

| Anthem: "La Perla del Sur"[3][4] | |

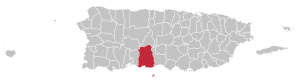

Map of Puerto Rico highlighting Ponce Municipality | |

| Coordinates: 18°0′39.132″N 66°36′50.1474″W / 18.01087000°N 66.613929833°W[5] | |

| Sovereign state | |

| Commonwealth | |

| Settled | c.1500 BC (Non-Europeans)[6][7][8] |

| Re-settled | 1582 (Europeans)[9][10][11] |

| Sitio | 1646 (Dispersed settlement)[12][13][14] |

| Partido | 1670 (Hamlet)[15][16][a] |

| Founded | August 12, 1692 (Village)[17][18][19][20] |

| † Villa | July 29, 1848 |

| † Ciudad | August 13, 1877[21] |

| Named for | Juan Ponce de Leon y Loayza |

| Barrios | |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Mayor | Marlese Sifre November 2, 2023. (PPD) |

| • Council | Asamblea Municipal de Ponce |

| Area | |

• City and municipality | 193.6 sq mi (501 km2) |

| • Land | 114.8 sq mi (297 km2) |

| • Water | 78.8 sq mi (204 km2) |

| Elevation | 52 ft (16 m) |

| Population | |

• City and municipality | 137,491 |

| • Rank | 4th in Puerto Rico |

| • Density | 710/sq mi (270/km2) |

| • Metro | 224,142 (MSA) |

| • CSA | 365,233 |

| Demonym | Ponceños |

| Time zone | UTC−4 (AST) |

| ZIP Codes | 00715, 00716, 00717, 00728, 00730, 00731, 00732, 00733, 00734, 00780 |

| Area code | 787/939 |

| Major routes | |

| GNIS feature ID | 1611718[22] |

| Website | http://visitponce.com/ |

| † = Date of the Villa and Ciudad charters | |

The city serves as the governmental seat of the autonomous municipality as well as the regional hub for various Government of Puerto Rico entities, such as the Judiciary of Puerto Rico. It is also the regional center for various U.S. Federal Government agencies. Ponce is a principal city of both the Ponce Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Ponce-Yauco-Coamo Combined Statistical Area with, as of the 2020 US Census, a population of 278,477 and 333,426 respectively.[29]

The municipality of Ponce, officially the Autonomous Municipality of Ponce, is located in the southern coastal plain region of the island, south of Adjuntas, Utuado, and Jayuya; east of Peñuelas; west of Juana Díaz; and bordered on the south by the Caribbean Sea. The municipality has 31 barrios, including 19 outside the city's urban area and 12 in the urban area of the city. It is the second largest in Puerto Rico by land area, and it was the first in Puerto Rico to obtain its autonomy, becoming the Autonomous Municipality of Ponce in 1992.

The historic Ponce Pueblo district, located in the downtown area of the city, is composed by several of the downtown barrios, and is located approximately three miles (4.8 km) inland from the Caribbean coast. The historic district is characterized for its Art Deco, Neoclásico Isabelino and Ponce Creole architectures.[30][31]

History

editEarly settlers

editThe region of what is now Ponce belonged to the Taíno Guaynia region, which stretched along the southern coast of Puerto Rico.[32] Agüeybaná, a cacique who led the region, was among those who greeted Spanish conquistador Juan Ponce de León when he came to the island in 1508. Archaeological findings have identified four sites within the municipality of Ponce with archaeological significance: Canas, Tibes, Caracoles, and El Bronce.[33]

During the first years of the colonization, Spanish families started settling around the Jacaguas River, in the south of the island.[34] For security reasons,[35] these families moved to the banks of the Rio Portugués, then called Baramaya.[36][37] Starting around 1646 the whole area from the Rio Portugués to the Bay of Guayanilla was called Ponce.[38][39] In 1670, a small chapel was raised in the middle of the small settlement and dedicated in honor of Our Lady of Guadalupe.[40] Among its earliest settlers were Juan Ponce de León y Loayza, and the Portuguese Don Pedro Rodríguez de Guzmán, from nearby San Germán.[41]

On September 17, 1692, the King of Spain Carlos II issued a Cédula Real (Royal Permit) converting the chapel into a parish, and in so doing officially recognizing the small settlement as a hamlet.[42] It is believed that Juan Ponce de León y Loayza, Juan Ponce de León's great-grandson, was instrumental in obtaining the royal permit to formalize the founding of the hamlet.[43] Captains Enrique Salazar and Miguel del Toro were also instrumental.[44] The city is named after Juan Ponce de León y Loayza,[45][46] the great-grandson of Spanish conquistador Juan Ponce de León.[47]

In the early 18th century Don Antonio Abad Rodriguez Berrios built a small chapel under the name of San Antonio Abad. The area would later receive the name of San Antón, a historically important part of modern Ponce.[48] In 1712 the village was chartered as El Poblado de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de Ponce (The Village of Our Lady of Guadalupe of Ponce).[49]

19th-century immigrants

editIn the early 19th century, Ponce continued to be one of dozens of hamlets that dotted the Island. Its inhabitants survived by subsistence agriculture, cattle raising, and maritime contraband with foreigners. Mayor José Benítez categorized the jurisdiction into cotos, hatos, criaderos, monterías, and terrenos realengos.[50] Cotos were lands awarded to residents as reward for their services to the king. They were developed into estancias or lands apt to be cultivated for agricultural use. Hatos were lands not granted to anyone in particular, but available for communal use where cattle could roam at will. Monterías were hilly areas located next to hatos were cattle could be reigned in or gathered together with the help of trained dogs. Criaderos were lands were cows could be herded for milk production. Goats, sheep, pigs, asses, and mares were also herded in criaderos. Terrenos realengos were lands that belonged to the state (to the king).[51][52]

However, in the 1820s, three events dramatically changed the size of the town. The first of these events was the arrival of a significant number of white Francophones, fleeing the Haitian Revolution of 1791–1804.[53] The effect of this mass migration was not felt significantly until the 1820s. These French Creole entrepreneurs were attracted to the area because of its large flatlands, and they came with enough capital, slaves, and commercial connections to stimulate Ponce's sugarcane production and sales.[54]

Secondly, landlords and merchants migrated from various Latin American countries. They had migrated for better conditions, as they were leaving economic decline following the revolutions and disruption of societies as nations gained independence from Spain in the 1810s-1820s.[53]

Third, the Spanish Royal Decree of Graces of 1815 attracted numerous European immigrants to Puerto Rico. It encouraged any citizen of a country politically friendly to Spain to settle in Puerto Rico as long as they converted to the Catholic faith and agreed to work in the agricultural business. With such mass migrations, not only the size of the town was changed, but the character of its population was changed as well. Europeans, including many Protestants, immigrated from a variety of nations.[55] On July 29, 1848, and as a result of this explosive growth, the Ponce hamlet was declared a villa (village) by Queen Isabella II,[56][57] and in 1877 the village obtained its city charter.[58][59]

Some of these immigrants made considerable fortunes in coffee, corn and sugarcane harvesting, rum production,[60] banking and finance, the importing of industrial machinery, iron foundries and other enterprises. At the time of the American invasion of the Island in 1898, Ponce was a thriving city,[61] boasting the Island's main financial center,[62] the Island's first communications link to another country,[63] the best capitalized financial institutions, and even its own currency.[64] It had consular offices for England, Germany, the Netherlands, and other nations.[65]

Following trends set in Europe and elsewhere, in 1877, Don Miguel Rosich conceived an exposition for Ponce. This was approved in 1880, and the Ponce Fair was held in the city in 1882. It showed several industrial and agricultural advancements.

"It is important to establish a relationship between the European exhibitions that I have mentioned and the Ponce Fair, as the Fair was meant as a showcase of the advancements of the day: Agriculture, Trade, Industry, and the Arts. Just as with the 1878 World's Fair in Paris, the electric grid of the city of Ponce was inaugurated on the first day of the Ponce Fair. In this occasion the Plaza Las Delicias and various other buildings, including the Mercantile Union Building, the Ponce Casino, and some of Ponce's homes were illuminated with the incandescent light bulb for the first time".[66]

Ponce in the 20th century

editU.S. invasion

editAt the time of the U.S. invasion and occupation of Puerto Rico in 1898 during the Spanish–American War, Ponce was the largest city in the island with a population of 22,000. Ponce had the best road in Puerto Rico, running from Ponce to San Juan, which had been built by the Spaniards for military purposes.[67] The taking of Ponce by American troops "was a critical turning point in the Puerto Rican campaign. For the first time the Americans held a major port to funnel large numbers of men and quantities of war material into the island." Ponce also had underwater telegraph cable connections with Jamaica and the West Indies, putting the U.S. forces on the island in direct communication with Washington, D.C., for the first time since the beginning of the campaign.[68] Just prior to the United States occupation of the island, Ponce was a flourishing and dynamic city with a significant number of public facilities, a large number of industries and commercial firms, and a great number of exquisite residences that reflected the high standing of its bourgeoisie.[69]

On July 27, American troops, aboard the Cincinnati, Dixie, Wasp, and Gloucester, disembarked at Playa de Ponce.[70] General Nelson Miles arrived the next day with reinforcements from Guánica and took possession of the city. There were some minor skirmishes in the city, but no major battle was fought. Three men were killed and 13 wounded on the Spanish side, while the Americans suffered four wounded. The American flag was raised in the town center that same day and most of the Spanish troops retreated into the surrounding mountains. The U.S. Army then established its headquarters in Ponce.[71]

Period of stagnation

editAfter the U.S. invasion, the Americans chose to centralize the administration of the island in San Juan,[72] the capital, neglecting the south and thus starting a period of socio-economic stagnation for Ponce.[73] This was worsened by several factors:

- Hurricane San Ciriaco in 1899 had left the region in misery[74][75]

- The opening of sugar mills in Salinas[76] and Guánica[77] drew commercial and agricultural activity away from Ponce[78]

- The decadence in coffee plantations in the 1920s[79][80][81]

- The loss of the Spanish and Cuban markets[82] "The Spanish American War had paralyzed the trade of the Island of Puerto Rico and when Spain surrendered the sovereignty she closed her [Spain's] ports to Puerto Rican products, while the American occupation of Cuba destroyed the only other important market. As a result, the trade in coffee and tobacco was ruined, and nothing was provided by the Americans to take their place."[83]

At least one author has also blamed the stagnation on "the strife between the U.S. and the local Nationalist Party."[84]

The 20th century financial stagnation prompted residents to initiate measures to attract economic activity back into the city. Also, a solid manufacturing industry surged that still remains. Examples of this are the Ponce Cement, Puerto Rico Iron Works, Vassallo Industries, and Destilería Serrallés. El Dia was also founded in Ponce in 1911.

Ponce massacre

editOn March 21, 1937, a peaceful march was organized by the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party to celebrate the 64th anniversary of the abolition of slavery and protest the incarceration of their leader, Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos, in a federal prison on charges of sedition.[85]

The march turned into a bloody event when the Insular Police, a force somewhat resembling the National Guard of the typical U.S. state and which answered to U.S.-appointed governor Blanton Winship, opened fire on unarmed and defenseless members of the Cadets of the Republic and bystanders.[85][86]

When the shooting stopped, nineteen civilians had been killed or mortally wounded.[87] Over two hundred others were badly wounded.[88] Many were shot in their backs while running away, including a seven-year-old girl named Georgina Maldonado who was "killed through the back while running to a nearby church."[89][90]

The US commissioned an independent investigation headed by Arthur Garfield Hays, general counsel of the American Civil Liberties Union, together with prominent citizens of Puerto Rico. The members concluded in their report that the event was a massacre, with the police acting as a mob. They harshly criticized Winship's actions as governor and said he had numerous abuses of civil rights.[91] The event has since been known as the Ponce massacre.[91] It was the largest massacre in Puerto Rican history.[92] As a result of this report and other charges against Winship, he was dismissed from his position in 1937 and replaced as governor.[91]

The history of this event can be viewed at the Ponce Massacre Museum on Marina Street. An open-air park in the city, the Pedro Albizu Campos Park, is dedicated to the memory of the president of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party. As a result of this event, Ponce has been identified as "the birthplace of Puerto Rican national identity."[93] Ponce history in general is expressed at the Ponce History Museum, on the block bordered by Isabel, Mayor, Cristina, and Salud streets in the historic downtown area.

Hub for political and economic activity

editPonce has continued to be a hub of political activity on the island, and is the founding site of several major political parties. It has also been the birthplace of several important political figures of the island, including Luis A. Ferré and Rafael Hernández Colón, both former governors of Puerto Rico, as well as the childhood town of governor Roberto Sanchez Vilella.

Statistics taken from the 2010 census show that 82.0% of Ponceños are white and 9.0% are African-American, with Taínos, Asians, people of mixed race and others making up the rest.[94] At 82.0% vs. 76.2% for the island as a whole, Ponce has the highest concentration of white population of any municipality in Puerto Rico.[95] However, the US Census Bureau changed the definitions of its racial makeup categories for the 2020 Census[96] resulting in 19.0% of Ponceños being classified as white and 13.3% as Black/Afro Puerto Rican', 0.3% as Asian, and people of mixed race making up the rest.

1970s economic decline

editThe 1970s brought significant commercial, industrial and banking changes to Ponce that dramatically altered its financial stability and outlook of the city, the municipality and, to an extent, the entire southern Puerto Rico region. After Luis A. Ferre concluded his term as governor of Puerto Rico on January 1, 1973, he closed the Puerto Rico Iron Works foundry on Avenida Hostos, and transferred the offices of Ponce's island-wide El Dia newspaper that he owned, as well as the headquarters of his Empresas Ferré, to San Juan. In 1976, CORCO—southern Puerto Rico's main source of economic vitality—shut down its industrial operations in Guayanilla leaving thousands of area residents without work; its impact on indirect sources of employment was even greater. Also, the sugar cane industry, also suffered a major downturn. Sugar cane had until 1976 been grown and refined at Ponce's Central Mercedita, but in that year agricultural production of sugar cane was halted in the lands of the municipality of Ponce and adjacent towns. Also, the headquarters of Banco de Ponce and Banco Crédito y Ahorro Ponceño were moved to San Juan. Unemployment of Ponce jumped to 25% as a result of these changes.[97]

The Mameyes landslide

editOn October 7, 1985, Ponce was the scene of a major tragedy, when at least 129 people lost their lives to a mudslide in a sector of Barrio Portugués Urbano[98] called Mameyes. International help was needed to rescue people and recover corpses. The United States and many other countries, including Mexico, France, and Venezuela, sent economic, human, and machinery relief. The commonwealth government, subsequently, relocated hundreds of people to a new community built on stable ground.[99] In 2005, the National Science and Technology Council's Subcommittee on Disaster Reduction of the United States reported that the Mameyes landslide held the record for having inflicted "the greatest loss of life by a single landslide" up to that year.[100]

Recent history

editThe municipality of Ponce became the first in Puerto Rico to obtain its autonomy[101] on October 27, 1992, under a new law (The Autonomous Municipalities Act of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico[102]) enacted by the Puerto Rican legislature. Ponce's mayor for 15 years, Rafael Cordero Santiago ("Churumba"), credited for leading the municipal government to that accomplishment, died in office on the morning of January 17, 2004, after suffering three consecutive strokes. Vice-mayor Delis Castillo Rivera de Santiago finished his term. Cordero was succeeded by Francisco Zayas Seijo. In the 2008 general elections María "Mayita" Meléndez was elected mayor of the city of Ponce and served three terms.[103] The current (2021) mayor is Luis Irizarry Pabón who became the first mayoral candidate in the modern history of Ponce to win with more than 60% of votes cast.[104]

The city is also the governmental seat of the Autonomous Municipality of Ponce, and the regional hub for various commonwealth entities. For example, it serves as the southern hub for the Judiciary of Puerto Rico.[105][106][107] It is also the regional center for various other commonwealth and federal government agencies.[108]

Ponce has improved its economy in the last years. In recent years, Ponce has solidified its position as the second most important city of Puerto Rico based on its economic progress and increasing population.[109] Today, the city of Ponce is the second largest in Puerto Rico outside of the San Juan metropolitan area.[110] Its nicknames include: La Perla del Sur (The Pearl of the South)[111] and La Ciudad Señorial (The Noble or Lordly City).[112] The city is also known as La Ciudad de las Quenepas (Genip City),[113][114] from the abundant amount of this fruit that grows within its borders. The complete history of Ponce can be appreciated at the Museo de la Historia de Ponce, which opened in the city in 1992. It depicts the history of the city from its early settlement days until the end of the 20th century.[115]

On September 20, 2017 Hurricane Maria struck the island of Puerto Rico. In Ponce, $1,000 million in damages were the initial estimates. An estimated 3,500 homes were completely or partially destroyed.[116] The hurricane triggered numerous landslides in Ponce.[117][118]

Geography

editThe Municipality of Ponce sits on the Southern Coastal Plain region of the Puerto Rico, on the shores of the Caribbean Sea. It is bordered by the municipalities of Adjuntas, Utuado, Jayuya, Peñuelas, and Juana Díaz.[119] Ponce is a large municipality, with only Arecibo larger in land area in Puerto Rico.[120] In terms of physical features, the municipality occupies a roughly rectangular area in south-central portion of the Island of approximately 10 miles (16 km) wide (east-to-west) by 13 miles (21 km) long (north-to-south).[121] It has a surface area of 116.0 square miles (300 km2).[122] The main physiographic features of the municipality of Ponce are: (1) the mountainous interior containing the headwaters of the main river systems, (2) an upper plain, (3) a range of predominantly east-west trending limestone hills, (4) a coastal plain, and (5) a coastal flat.[123] The northern two-thirds of the municipality consists of the mountainous interior, with the southern third divided between hills, coastal plains, and the coastal flat.[124]

Ponce's municipal territory reaches the central mountain range to the north and the Caribbean Sea to the south. Geographically speaking, the southern area of the territory is part of the Ponce-Patillas alluvial plain subsector and the southern coastal plain, which were created by the consolidation of the valleys of the southern side of the central mountain range and the Cayey mountain range. The central area of the municipality is part of the semi-arid southern hills. These two regions are classified as being the driest on the island. The northern part of the municipality is considered to be within the rainy western mountains.[125] Barrio Anón is home to Cerro Maravilla, a peak that at 4,085 feet (1,245 m) is Puerto Rico's fourth highest peak.[126]

Nineteen barrios[127] comprise the rural areas of the municipality, and the topology of their lands varies from flatlands to hills to steep mountain slopes. The hilly barrios of the municipality (moving clockwise around the outskirts of the city) are these seven: Quebrada Limón, Marueño, Magueyes, Tibes, Portugués Rural, Machuelo Arriba, and Cerrillos. The barrios of Canas, Coto Laurel, Capitanejo, Sabanetas, Vayas, and Bucaná also surround the outskirts of the city but these are mostly flat. The remaining six other barrios are further away from the city and their topology is rugged mountain terrain. These are (clockwise): Guaraguao, San Patricio, Monte Llano, Maragüez, Anón, and Real. The ruggedness of these barrios is because through these areas of the municipality runs the Central Mountain Range of the Island.[128] The remaining barrios are part of the urban zone of the city.[129][130] There are six barrios in the core urban zone of the municipality named Primero, Segundo, Tercero, Cuarto, Quinto, and Sexto. They are delimetered by streets, rivers, or major highways. For example, Barrio Tercero is bounded in the north by Isabel Street, in the east by the Rio Portugués, in the south by Comercio Street, and the west by Plaza Las Delicias.[131] Barrio Tercero includes much of what is called the historic district.

There is a seismic detector that the University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez Campus, has placed in Barrio Cerrillos.[132]

Land features

editElevations include Cerro de Punta at 4,390 feet (1,340 m), the highest in Puerto Rico, located in Barrio Anón in the territory of the municipality of Ponce.[133][134] Mount Jayuya, at 4,314 feet (1,315 m) is located on the boundary between Barrio Anón and Barrio Saliente in Jayuya. Cerro Maravilla, at nearly 3,970 feet (1,210 m) above sea level, is located to the east of Barrio Anón. There are many other mountains at lower elevations in the municipality, such as the Montes Llanos ridge and Mount Diablo, at 2,231 feet (680 m) and Mount Marueño, at 2,100 feet (640 m), and Pinto Peak, among others. Part of the Toro Negro Forest is located in Barrio Anón. Coastal promontories include Cuchara, Peñoncillo, Carnero, and Cabullón points.[135] Fifty-six percent of the municipality consists of slopes 10 degrees or greater.[136]

Water features

editThe 14 rivers comprising the hydrographic system of Ponce are Matilde, Inabón, Bucaná, Jacaguas, Portugués, Cañas, Pastillo, Cerrillos, Chiquito, Bayagan, Blanco, Prieto, Anón and San Patricio[137] The Jacaguas River runs for a brief stretch on the southeast area of the municipality. The Inabón River springs from Anón ward and runs through the municipality for some 18 mi (29.0 km); the tributaries of the Inabón are the Anón and Guayo rivers and the Emajagua Brook. The Bucaná River springs from Machuelo Arriba ward and runs for 18.5 mi (29.8 km) into the Caribbean Sea. The tributaries of the Bucaná are the San Patricio, Bayagán, and Prieto Rivers and Ausubo brook. The Portugués River springs from the ward of that name in Adjuntas, and runs for 17.3 mi (27.8 km) into the Caribbean sea at Ponce Playa ward. The Matilde River, also known as the Pastillo River, runs for 12 mi (19 km); its tributaries are the Cañas River and the Limón and del Agua brooks. Lakes in Ponce include Bronce and Ponceña as well as lakes bearing numbers: Uno, Dos, Tres, and Cinco; and the Salinas Lagoon, which is considered a restricted lagoon.[138] Other water bodies are the springs at Quintana and the La Guancha and El Tuque beaches.[139] There is also a beach at Caja de Muertos Island. Lake Cerrillos is located within the limits of the municipality,[140] as will be the future lake resulting from the Portugués Dam. The Cerrillos State Forest is also located in the municipality of Ponce.

Coastal geographic features in Ponce include Bahía de Ponce, Caleta de Cabullones (Cabullones Cove), and five cays: Jueyes, Ratones,[141] Cardona, Gatas, and Isla del Frio.[142] Caja de Muertos Island and Morrillito islet are located at the boundary between Ponce and Juana Díaz. There is a mangrove covering an area of approximately 100 acres (40 ha) at Cabullón promontory and Isla del Frio. The Salinas Lagoon, part of Reserva Natural Punta Cucharas, has a mangrove that expands about 37 acres (15 ha). The lagoon itself consists of 698 cuerdas (678 acres; 274 ha).[143] The Rita cave is located in Barrio Cerrillos.[144]

Climate

editPonce features a tropical savanna climate (Koppen Aw/As). Ponce has summer highs averaging 92 °F (33 °C)[145] and winter highs, 87 °F (31 °C).[146] It has lows averaging 67 °F (19 °C) in the winter[146] and 74 °F (23 °C) in the summer.[147] It has a record high of 100 °F (38 °C), which occurred on 21 August 2003,[148] and a record low of 51 °F (11 °C) which occurred on 28 February 2004, tying the record low of 51 °F (11 °C) from 25 January 1993.[149] The mean annual temperature in the municipality is 79 °F (26 °C).[150]

| Climate data for Ponce, Puerto Rico (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1898–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 98 (37) |

95 (35) |

96 (36) |

96 (36) |

96 (36) |

99 (37) |

100 (38) |

100 (38) |

99 (37) |

98 (37) |

100 (38) |

98 (37) |

100 (38) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 87.8 (31.0) |

87.7 (30.9) |

87.6 (30.9) |

88.8 (31.6) |

89.5 (31.9) |

91.2 (32.9) |

91.5 (33.1) |

91.8 (33.2) |

91.4 (33.0) |

90.8 (32.7) |

89.8 (32.1) |

88.4 (31.3) |

89.7 (32.1) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 75.1 (23.9) |

74.9 (23.8) |

75.0 (23.9) |

76.7 (24.8) |

78.3 (25.7) |

80.2 (26.8) |

80.3 (26.8) |

80.5 (26.9) |

80.0 (26.7) |

79.4 (26.3) |

77.9 (25.5) |

75.9 (24.4) |

77.8 (25.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 62.5 (16.9) |

62.1 (16.7) |

62.5 (16.9) |

64.6 (18.1) |

67.0 (19.4) |

69.2 (20.7) |

69.1 (20.6) |

69.3 (20.7) |

68.7 (20.4) |

67.9 (19.9) |

66.0 (18.9) |

63.5 (17.5) |

66.0 (18.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 49 (9) |

51 (11) |

50 (10) |

53 (12) |

55 (13) |

60 (16) |

58 (14) |

60 (16) |

58 (14) |

61 (16) |

56 (13) |

52 (11) |

49 (9) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.73 (19) |

1.21 (31) |

1.87 (47) |

2.26 (57) |

4.18 (106) |

2.16 (55) |

2.84 (72) |

4.56 (116) |

6.94 (176) |

5.38 (137) |

3.94 (100) |

1.45 (37) |

37.52 (953) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 6.0 | 6.5 | 7.0 | 8.7 | 10.1 | 7.8 | 8.2 | 10.3 | 12.1 | 12.7 | 10.1 | 7.4 | 106.9 |

| Source: NOAA[151][152] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

editArchitecture

editDuring the 19th century, the city was witness to a flourishing architectural development, including the birth of a new architectural style later dubbed Ponce Creole. Architects like Francisco Valls, Manuel Víctor Domenech, Eduardo Salich, Blas Silva Boucher, Agustín Camilo González, Alfredo Wiechers, Francisco Porrata Doria and Francisco Gardón Vega used a mixture of Art Nouveau and neoclassic styles to give the city a unique look. This can be seen in the various structures located in the center of the city like the Teatro La Perla. To showcase its rich architectural heritage, the city has opened the Museum of Puerto Rican Architecture at the Wiechers-Villaronga residence.[153][154]

Many of the city's features (from house façades to chamfered street corners) are modeled on Barcelona's architecture, given the city's strong Catalan heritage. In 2020, the National Trust for Historic Preservation named the Ponce Historic Zone as one of America's most endangered historic places.[155]

Barrios

editWith 31 barrios, Ponce is Puerto Rico's municipality with the largest number of barrios.[156][157][158][159] Ponce's barrios consist of 12 located in the urban area of the city plus 19 outside the urban zone.[160][161] Of these nineteen, seven were considered suburban in 1999. The suburban barrios were: Canas, Magueyes, Portugués, Machuelo Arriba, Sabanetas, Coto Laurel, and Cerrillos.[162] A 2000 report by the U.S. Census Bureau provides detailed demographics statistics for each of Ponce's barrios.[163]

The 2000 Census showed that Montes Llanos is the least populated barrio in the municipality. Thanks to its larger area, barrio Canas was by far the most populated ward of the municipality.[164] At 68 persons per square mile, San Patricio was the least populated, while Cuarto was the most densely populated at 18,819 persons per square mile.

Ponce has nine barrios that border neighboring municipalities. These are Canas, Quebrada Limón, Marueño, Guaraguao, San Patricio, Anón, Real, Coto Laurel, and Capitanejo. Canas and Capitanejo are also coastal barrios, and together with three others (Playa, Bucaná, and Vayas) make up the municipality's five coastal barrios.

There are also five barrios within the city limits (Canas Urbano, Machuelo Abajo, Magueyes Urbano, Portugués Urbano, and San Antón) that in addition to the original six city core barrios — named Primero, Segundo, Tercero, Cuarto, Quinto, and Sexto — make up the 11 urban zone barrios of the municipality. The historic zone of the city is within these original six core city barrios. These eleven barrios composed what is known as the urban zone of the municipality.

The remaining eight barrios (Magueyes, Tibes, Montes Llanos, Maragüez, Portugués, Machuelo Arriba, Cerrillos, Sabanetas) are located in the interior of the municipality. These last eight are outside the city limits and are neither coastal nor bordering barrios.[165]

A summary of all the barrios of the municipality, their population, population density, and land and water areas as given by the U.S. Census Bureau is as follows:[166][167][168]

| No. | Barrio | Population (Census 2000) |

Density (/sq mi) |

Total Area (sq mi) |

Land Area (sq mi) |

Water Area (sq mi) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anón | 1669 | 129.9 | 12.85 | 12.85 | 0.00 |

| 2 | Bucaná | 3963 | 2957.5 | 2.16 | 1.34 | 0.81 |

| 3 | Canas | 34065 | 2349.3 | 22.82 | 14.50 | 8.32 |

| 4 | Canas Urbano | 21482 | 9299.6 | 2.31 | 2.31 | 0.00 |

| 5 | Capitanejo | 1401 | 355.4 | 4.82 | 3.95 | 0.88 |

| 6 | Cerrillos | 4284 | 1377.5 | 3.31 | 3.11 | 0.20 |

| 7 | Coto Laurel | 5285 | 1492.9 | 3.60 | 3.54 | 0.06 |

| 8 | Cuarto | 3011 | 18818.8 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.00 |

| 9 | Guaraguao | 1017 | 247.4 | 4.11 | 4.11 | 0.00 |

| 10 | Machuelo Abajo | 13302 | 7515.3 | 1.86 | 1.77 | 0.90 |

| 11 | Machuelo Arriba | 13727 | 2124.9 | 6.61 | 6.46 | 0.15 |

| 12 | Magueyes | 6134 | 1345.2 | 4.56 | 4.56 | 0.00 |

| 13 | Magueyes Urbano | 1332 | 1074.2 | 1.24 | 1.24 | 0.00 |

| 14 | Maragüez | 754 | 142.0 | 6.42 | 5.31 | 1.11 |

| 15 | Marueño | 1474 | 350.1 | 4.21 | 4.21 | 0.00 |

| 16 | Montes Llanos | 462 | 214.9 | 2.15 | 2.15 | 0.00 |

| 17 | Playa | 16926 | 3864.4 | 14.98 | 4.38 | 10.60 |

| 18 | Portugués | 4882 | 1386.9 | 3.56 | 3.52 | 0.04 |

| 19 | Portugués Urbano | 5886 | 5163.2 | 1.14 | 1.14 | 0.00 |

| 20 | Primero | 3550 | 14200.0 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.00 |

| 21 | Quebrada Limón | 804 | 301.1 | 2.67 | 2.67 | 0.00 |

| 22 | Quinto | 724 | 6581.8 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.00 |

| 23 | Real | 3139 | 595.6 | 5.28 | 5.27 | 0.01 |

| 24 | Sabanetas | 6420 | 2351.6 | 2.79 | 2.73 | 0.06 |

| 25 | San Antón | 11271 | 10063.4 | 1.17 | 1.12 | 0.04 |

| 26 | San Patricio | 465 | 67.8 | 6.86 | 6.86 | 0.00 |

| 27 | Segundo | 11321 | 17416.9 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.00 |

| 28 | Sexto | 4745 | 18250.0 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.01 |

| 29 | Tercero | 773 | 9662.5 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.00 |

| 30 | Tibes | 866 | 123.5 | 7.01 | 7.01 | 0.00 |

| 31 | Vayas | 1338 | 187.9 | 10.47 | 7.12 | 3.35 |

| Ponce | 186475 | 1625.5 | 193.6 | 114.7 | 78.9 |

Tourism

editDue to its historical importance throughout the years, Ponce features many points of interest for visiting tourists.[169] The downtown area contains the bulk of Ponce's tourist attractions.[170] Tourism has seen significant growth in recent years. In 2007, over 6,000 tourists visited the city via cruise ships.[171] Passenger movement at the Mercedita Airport in FY 2008 was 278,911, a 1,228% increase over fiscal year 2003 and the highest of all the regional airports for that 5-year period.[172] Though not all of these were tourists, it represents a volume larger than the population of the city itself.

To support a growing tourist industry, around the 1970s, and starting with the Ponce Holiday Inn, several hotels have been built. Newer lodging additions include the Ponce Hilton Golf & Casino Resort, home to the new Costa Caribe Golf & Country Club, featuring a 27-hole PGA championship golf course. The Hotel Meliá has operated in the city continuously since the early 20th century. It has also been studied that the Intercontinental Hotel, which opened in February 1960 and closed in 1975, could be refurbished and re-opened atop the hill near Cruceta del Vigía as the "Magna Vista Resort".[173] The Ponce Ramada also opened in 2009, and other hotel projects in the works include the Four Points by Sheraton, and Marriott Courtyard, among others.[174] In 2013, the downtown Ponce Ramada Hotel added a casino to its 70-room structure.[175][176] Ponce is part of the Government of Puerto Rico's Porta Caribe tourist region.

| External audio | |

|---|---|

| You may a see a video on Ponce's tourist attractions HERE |

Ponce en Marcha

editIn recent years an intensive $440 million[177][178] revitalization project called "Ponce en Marcha"[179] ("Ponce on the Move") has increased the city's historic area from 260 to 1,046 buildings.[180] The Ponce en Marcha[d] project was conceived in 1985 by then governor Rafael Hernández Colón during his second term in La Fortaleza and Ponce mayor Jose Dapena Thompson.[181][182] The plan was approved by the Ponce Municipal Legislature on January 14, 2003. It was signed by Governor Sila Calderon via Executive Order on December 28, 2003, and went into effect on January 12, 2004. The plan incorporates one billion dollars in spending during the period of 2004 through 2012.[183] A significant number of buildings in Ponce are listed in the National Register of Historic Places.[184] The nonprofit Project for Public Places[185] listed the historic downtown Ponce city center as one of the 60 of the World's Great Places, for its "graciously preserved showcase of Caribbean culture".[186] The revitalized historic area of the city goes by various names, including "Ponce Centro" (Ponce Center),[187] "Historic Ponce",[188] and "Historic District."[189] The name "Ponce en Marcha" comes from the revitalization plan of Zona Atocha in Madrid called Atocha en Marcha.[190]

Landmarks

editThe city has been christened as Museum City for its many quality museums.[191][192] All museums in Ponce are under municipal government administration. On 15 September 2004, the last four museums not under local control were transferred from the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture to the Ponce Municipal Government by act of the Puerto Rico Legislature.[193] However, these four museums (Casa Armstrong Poventud, Casa Wiechers-Villaronga, Museo de la Música Puertorriqueña, and Casa de la Masacre) continue to be controlled by the ICP.[194][195] Downtown Ponce in particular features several museums and landmarks.[196]

Plaza Las Delicias, the town's main square, features a prominent fountain (namely, the "Lions Fountain"), the Ponce Cathedral, and Parque de Bombas, an old fire house, now a museum, that stands as an iconic symbol of the city and a tribute to the bravery of its firefighters. This plaza is also a usual gathering place for "ponceños". Other buildings around Ponce's main plaza include the Casa Alcaldía (Ponce City Hall), the oldest colonial building in the city, dating to the 1840s, and the Armstrong-Poventud Residence, an example of the neoclassical architectural heritage of the island.

Just north of downtown Ponce lies the Castillo Serrallés and the Cruceta del Vigía, a 100-foot (30 m) observation tower which overlooks the city. The Serralles castle is reported to receive nearly 100,000 visitors every year.[197] The hill on which the Cruceta is located was originally used by scouts to scan for incoming mercantile ships as well as invading ones. The invasion of American troops in 1898 was first spotted from there.

Ponce is home to Puerto Rico's oldest cemetery; in fact, it is the oldest cemetery in the Antilles. In the city outskirts, the Tibes Indigenous Ceremonial Center was discovered in 1975 after hurricane rains uncovered pottery.[198] The center is the site of the oldest cemetery uncovered up to date in the Antilles. With some 200 skeletons unearthed from the year 300 AD, it is considered the largest and the most important archaeological finding in the West Indies.[199][200] Two other cemeteries in Ponce worth noting are the Panteón Nacional Román Baldorioty de Castro and the Cementerio Catolico San Vicente de Paul, both of which are listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The Cementerio Catolico San Vicente de Paul has the most eye-catching burial constructions of any cemetery for the wealthiest families, both local and foreign-born, of southern Puerto Rico.[201]

Also in the city outskirts is Hacienda Buena Vista, an estate built in 1833 originally to grow fruits. It was converted into a coffee plantation and gristmill in 1845. It remained in operation until 1937, then fell into disrepair, but was restored by the government's Fideicomiso de Conservación de Puerto Rico. All the machinery works (the metal parts) are original, operated by water channeled from the 360m Vives waterfall; there is a hydraulic turbine which makes the corn mill work.

Paseo Tablado La Guancha is located in the town's sea shore. It features kiosks with food and beverages, an open-space stage for activities, and a marina called Club Náutico de Ponce. From the observation tower on the boardwalk, Cardona Island Light can be seen. A 45-minute boat ride is also available to Isla de Caja de Muertos (Coffin Island), a small island with several beaches and an 1887 lighthouse.

As of 2008[update], the city had also engaged in the development of a convention center with a capacity for 3,000 people. It is also to include two major hotels, apartment buildings and recreational facilities.[202] Puerto Rico Route 143 (PR-143), known as the Panoramic Route, runs edging near the municipality's northern border.[203]

Culture

editThe city is home to a long list of cultural assets including libraries, museums, galleries, and parks, hundreds of buildings of historical value including schools, residences, bridges, and estates, and frequent activities such as festivals and carnivals. The municipality invests close to half a million dollars in promoting its cultural assets.[204] It established its first library in 1894[205] and, as of 2007[update] had a new central library[206] with seven other branches scattered throughout the municipality.[207]

A number of cultural events take place during the year, most prominently:[208][209]

- February – Ponce Carnival

- March – Feria de Artesanías de Ponce (Ponce Crafts Fair)[210] In 2019, the 45th Feria de Artesanías de Ponce was held.[211]

- April – Ponce Jazz Festival

- May –— Fiesta Nacional de la Danza; Barrio Playa Festival

- July – Barrio San Anton's Bomba Festival

- August – Festival Nacional de la Quenepa (National Genip Festival), often the third week[212][213]

- September – Día Mundial de Ponce

- November – Discovering Our Indian Roots

- December – Patron Saint's Day Festival (Fiestas Patronales);[214] Las Mañanitas;[214] Children's Christmas Concert

The city values its cultural traditions as evidenced by the revitalization project Ponce en Marcha. It is deeply rooted in its traditional cultural, artistic, and musical heritage. The love for art and architecture, for example, can be appreciated at its museums of art, music, and architecture.

"Over the last century or so, the north [i.e., San Juan] willingly accepted the influence of western culture with its tendency toward large sprawling metropolises, and the displacement of old values and attitudes. Ponce, on the other hand, has been content to retain its old traditions and culture. Ponce is not concerned about losing its long standing position as the second largest city in population after San Juan. On the contrary, she prefers to maintain her current size, and stick to its old traditions and culture."[215][216]

Some argue that the Ponceño culture is different from the rest of the Island:

"Ponceños have always been a breed apart from other Puerto Ricans. Their insularity and haughtiness are legendary, and some Puerto Ricans claim that even the dialect in Ponce is slightly different from that spoken in the rest of the Island. They are also racially different: you'll see more people of African descent in Ponce than anywhere else in the Island except Loiza."[217]

Others claim that Ponceños exhibit considerable more civic pride than do residents of other locales.[218] Luis Muñoz Rivera, the most important statesman in the Island at the close of the 19th century, referred to Ponce as "the most Puerto Rican city of Puerto Rico."[219][e]

Music

editArtistic development also flourished during this period. The surging of popular rhythms like Bomba and Plena took place in the south region of the island, mainly in Ponce. Barrio San Antón is known as one of the birthplaces of the rhythm. Every July, Ponce celebrates an annual festival of Bomba and Plena, which includes various musicians and parades.

Immigrants from Spain, Italy, France, Germany, and England came to Ponce to develop an international city that still maintains rich Taíno and African heritage. The African personality, belief, and music add flavor and colorful rhythm to Ponce's culture. Part of this are the influences of the Bomba and Plena rhythms. These are a combination and Caribbean and African music.[220]

Ponce has also been the birthplace of several singers and musicians. From opera singers like Antonio Paoli, who lived in the early 20th century, to contemporary singers like Ednita Nazario. Also, Salsa singers like Héctor Lavoe, Cheo Feliciano, and Ismael Quintana also come from the city.

Dating back to 1858, Ponce's Carnival is the oldest in Puerto Rico, and acquired an international flavor for its 150th anniversary.[221] It is one of the oldest carnivals celebrated in the Western Hemisphere. It features various parades with masked characters representative of good and evil.

The Museum of Puerto Rican Music, located at the Serrallés-Nevárez family residence in downtown Ponce, illustrates music history on the Island, most of which had its origin and development in Ponce.[222]

No discussion of music in Ponce would be complete without rendering honor to the great performances of King of Tenors Antonio Paoli and danza master Juan Morel Campos, both from Ponce. Today, there is a statue of Juan Morel Campos that adorns the Plaza Las Delicias city square, and the home where Paoli was born and raised functions as the Puerto Rico Center for Folkloric Research, a research center for Puerto Rican culture.

A municipal band presents concerts every Sunday evening, and a Youth Symphony Orchestra also performs.[223]

Arts

editPonce's love for the arts dates back to at least 1864 when the Teatro La Perla was built. Ponce is also the birthplace of artists like Miguel Pou, Horacio Castaing, and several others in the fields of painting, sculpture, and others. The City is one of only seven cities in the Western Hemisphere (the others being Mexico City, Havana, Valparaíso, Buenos Aires, Mar del Plata, and Rosario) in the Ruta Europea del Modernisme,[225] an international non-profit association for the promotion and protection of Art Nouveau heritage in the world.[226]

Today, Ponce has more museums (nine) than any other municipality in the Island.[227] Ponce is home to the Museo de Arte de Ponce (MAP), founded in 1959 by fellow ponceño Luis A. Ferré. The museum was operated by Ferré until his death at the age of 99, and it is now under the direction of the Luis A. Ferré Foundation. Designed by Edward Durell Stone, architect of Radio City Music Hall[228] and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, MAP is the only museum of international stature on the Island, the only one that was accredited by the American Alliance of Museums (AAM),[229] and the only one that has received a design prize of honor from the American Institute of Architects (AIA).[230] It houses the most extensive art collection in the Caribbean with 4,500 pieces.[231]

Sports

editMost of Ponce's professional teams are called the Leones de Ponce (Ponce Lions, or Ponce Lionesses as the case may be) regardless of the sport. The Leones de Ponce basketball team is one of the leading teams of the island, winning 12 championships during their tenure.[232] The team's venue is the Juan Pachín Vicéns Auditorium. The Leones de Ponce (men's) baseball and the Leonas de Ponce (women's) baseball teams have also been fairly successful.[233] The baseball teams' venue is the Francisco Montaner Stadium.[234] The stadium is located next to the Juan Pachín Vicéns Auditorium.[235]

In 1993 the city hosted the Central American and Caribbean Games, from November 19–30.[236]

The city also hosts two international annual sporting events. In the month of May, it hosts the Ponce Grand Prix, a track and field event in which over 100 athletes participate. During the Memorial Day Weekend in the month of September, the city hosts Cruce a Nado Internacional, a swimming competition with over a dozen countries represented. Also, the Ponce Marathon takes place every December, sometimes as part of the Las Mañanitas event on December 12.

The Francisco "Pancho" Coimbre Sports Museum, named after the baseball player of the same name, was dedicated to the honor of Puerto Rico's great sports men and women.[237] It is located on the grounds of the Charles H. Terry Athletic Park on Lolita Tizol Street, just north of the entrance to Historic Ponce at Puente de los Leones (Lions' Bridge) and the Ponce Tricentennial Park. In 2012 the city commenced construction of the multi-sport complex Ciudad Deportiva Millito Navarro. No date has been announced for its completion yet, but its skateboarding section opened in March 2013.

The main annual sports events are as follows:

- April – Las Justas – intercollegiate sports competition

- May – Ponce Grand Prix – international track and field competition

- August – Cruce a Nado Internacional – international swimming competition

- December – Maratón La Guadalupe– - 26-mile national marathon

Recreation

editThe municipality is home to several parks and beaches, including both passive and active parks. Among the most popular passive parks are the Julio Enrique Monagas Family Park on Ponce By-pass Road (PR-2) at the location where the Rio Portugués feeds into Bucaná. The Parque Urbano Dora Colon Clavell, another passive park is in the downtown area. Active parks include the Charles H. Terry Athletic Field, and several municipal tennis courts, including one at Poly Deportivos with 9 hard courts, and one at La Rambla with six hard courts.[238] There are also many public basketball courts scattered throughout the various barrios of the municipality.

The municipality has 40 beaches including 28 on the mainland and 12 in Caja de Muertos.[239] Among these, about a dozen of them are most notable, including El Tuque Beach in the El Tuque sector on highway PR-2, west of the city, La Guancha Beach at the La Guancha sector south of the city, and four beaches in Caja de Muertos: Pelicano, Playa Larga, Carrucho, and Coast Guard beach.[240] A ferry must be boarded at La Guancha for transportation to the Caja de Muertos beaches.

Religion

editDuring and after colonization, the Roman Catholic Church became the established religion of the colony. Gradually African slaves were converted to Christianity, but many incorporated their own traditions and symbols, maintaining African traditions as well. Ponce Cathedral, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, was built in 1839.[241][242] The Royal Decree of Graces of 1815 allowed for non-Catholics to immigrate legally to Puerto Rico, but it required those who wanted to settle on the island to make a vow of alliance to the Catholic Church. Ponce was the first city in Puerto Rico where Protestant churches were built.[243]

With the U.S. invasion, there was a significant change in the religious landscape in the City and in Puerto Rico. "The Protestant missionaries followed the footprints of the United States soldiers, right after the Treaty of Paris was ratified and Puerto Rico was ceded to the American government."[244] By March 1899, eight months after the occupation, executives from the Methodists, Episcopalians, Baptists, Presbyterians, and others, had arranged for an evangelical division whereby Ponce would have Evangelical, Baptist, and Methodist "campaigns". With the passing of the Foraker Act in 1900, which established total separation between Church and State, the absolute power of the Catholic Church eroded quickly.[244]

Various Protestant churches were soon established and built in Ponce; today many are recognized as historic sites. Among them are the McCabe Memorial Church (Methodist) (1908),[245] and the Missionary Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church (Methodist) (1907).[246]

The bell of the Episcopalian Holy Trinity Church in Barrio Cuarto, rang again[247] when the Americans arrived on 25 July 1898. Built in 1873, the church was allowed to function by the Spanish Crown under the conditions that its bell would not be rung, its front doors would always remain closed, and its services would be offered in English only.[248]

Today, Ponce is home to a mix of religious faiths: both Protestants and Catholics, as well as Muslims, have places of worship in Ponce. Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, Episcopalians, Pentecostals, Adventists, Evangelicals, Disciples of Christ, and Congregationalists are among the Protestant faiths with a following in Ponce. Catholicism is the faith of the majority of ponceños. In 2009, the Catholic Church had 18 parishes in the municipality, two bishops and 131 priests.[249] In his Memoirs, Albert E. Lee summed up Ponce's attitude towards religion:

Ponce was not only tolerant, it was indifferent in religious matters. Protestants and Catholics, and even atheists, lived together socially on the friendliest terms. Religion was strictly a personal affair in Ponce while in San Juan at times gave the impression that it was ready to practice the auto-de-fe [sic]."[250]

Economy

editTraditionally the city's economy had depended almost entirely on the sugarcane industry.[252] Since around the 1950s, however, the town's economy has diversified and today its economy revolves around a mixed-industry manufacturing sector, retail, and tourism.[253][254] The building of a mega port, anticipated to be completed in 2012,[255] is expected to add significantly to the area's economy. Agriculture, retail, and services are also significant players in the local economy. It is considered an agricultural, trade, and distribution center, with manufacturing that includes electronics, communications equipment, food processing, pharmaceutical drugs, concrete plants, scientific instruments and rum distilling as well as an established gourmet coffee agricultural industry.[256] The city, though, suffers from an unemployment rate that hovers around the 15 percent mark.[257]

Manufacturing

editThe municipality is considered one of the most developed municipalities in Puerto Rico.[258] Its manufacturing sectors include electronic and electrical equipment, communications equipment, food processing, pharmaceutical drugs, concrete plants, and scientific instruments.[256] It also produces leather products, needlework, and fish flour to a lesser extent. Ponce is home to the Serralles rum distillery, which manufactures Don Q, and to Industrias Vassallo, a leader in PVC manufacturing. Other important local manufacturers are Ponce Cement, Cristalia Premium Water, Rovira Biscuits Corporation, and Café Rico. Ponce was once the headquarters for Puerto Rico Iron Works, Ponce Salt Industries, and Ponce Candy Industries.

Agriculture

editIn the agricultural sector, the most important products are coffee, followed by plantains, bananas, oranges, and grapefruits. A mix of public and private services, as well as finance, retail sales, and construction round up Ponce's economic rhythm.[259] Cafe Rico, which metamorphosed from coffee-grower Cafeteros de Puerto Rico, has its headquarters in Ponce.

Retail

editFor many years commercial retail activity in Ponce centered around what is now Paseo Atocha. This has shifted in recent years, and most retail activity today occurs in one of Ponce's various malls, in particular Plaza del Caribe. Centro del Sur Mall is also a significant retail area, as is Ponce Mall.[260]

Mega port

editPonce is home to Puerto Rico's chief Caribbean port, the Port of Ponce.[261] The port is expanding to transform it into a mega port, called the Port of the Americas that will operate as an international transshipment port. When fully operational, it is expected to support 100,000 jobs.[262]

Demographics

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1765 | 3,314 | — |

| 1776 | 5,674 | +71.2% |

| 1800 | 7,234 | +27.5% |

| 1824 | 9,878 | +36.5% |

| 1828 | 14,927 | +51.1% |

| 1836 | 16,970 | +13.7% |

| 1846 | 21,799 | +28.5% |

| 1857 | 20,205 | −7.3% |

| 1860 | 28,156 | +39.4% |

| 1876 | 33,514 | +19.0% |

| 1887 | 42,388 | +26.5% |

| 1897 | 49,000 | +15.6% |

| Sources: Govt of Ponce[263] and Freepages | ||

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 55,477 | — |

| 1910 | 63,444 | +14.4% |

| 1920 | 71,426 | +12.6% |

| 1930 | 87,604 | +22.7% |

| 1940 | 105,116 | +20.0% |

| 1950 | 126,810 | +20.6% |

| 1960 | 145,586 | +14.8% |

| 1970 | 158,891 | +9.1% |

| 1980 | 189,046 | +19.0% |

| 1990 | 187,749 | −0.7% |

| 2000 | 186,475 | −0.7% |

| 2010 | 166,327 | −10.8% |

| 2020 | 137,491 | −17.3% |

| Source: "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 13, 2006. | ||

| Race - Ponce, Puerto Rico - 2020 Census[94] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Race | Population | % of Total |

| White | 26,148 | 19.0% |

| Black/Afro Puerto Rican | 18,325 | 13.3% |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 4,129 | 3.0% |

| Asian | 365 | 0.3% |

| Two or more races/Some other race | 88,524 | 64.4% |

Ponce has consistently ranked as one of the most populous cities in Puerto Rico. Ponce's population, according to the 2010 census, stands at 166,327, with a population density of 1,449.3 persons per square mile (559.6 persons/km2), ranking third in terms of population among Puerto Rican municipalities. As of 2000, speakers of English as a first language accounted for 13.89% of the population. [264]

Government

editThe municipal government has its seat in the city of Ponce.[265][266] Since its foundation in 1692, the city of Ponce has been led by a mayor. Its first mayor was Don Pedro Sánchez de Matos. The 2008 election of María Meléndez Altieri (PNP), brought Ponce the first woman to be elected to the mayoral office in the city's history. She was re-elected in 2012 and again in 2016, and serve as mayor until 2021. In the 2020 election Luis Irizarri Pabón (PPD) was elected as mayor and is currently serving as mayor.[267] Ponce's best known mayor of recent years is perhaps Rafael "Churumba" Cordero Santiago (PPD), who held office from 1989 until his sudden death on the morning of 17 January 2004, after suffering three successive brain strokes.

The city also has a municipal legislature that handles local legislative matters. Ponce has had a municipal council since 1812.[268][f][269] The municipal legislature is composed of 16 civilians elected during the general elections, along with the mayor, state representatives and senators. The delegations are, until the 2020 general election, distributed as follows: 13 legislators of the Popular Democratic Party, two legislators of the New Progressive Party, and one legislator from the Movimento Victoria Ciudadana.

The Ponce City Hall has one of the most unusual histories of any city hall throughout the world. "Originally built in the 1840s as a public assembly hall, Ponce's City Hall was a jail until the end of the 19th century. Current galleries were former cells, and executions were held in the courtyard. Four U.S. presidents spoke from the balcony - Theodore Roosevelt, Herbert Hoover, Franklin Roosevelt and George Bush." It is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.[270]

In 2005, the municipality's budget was US$152 million.[271] In 2010-2011 it was $158 million.[272] In 2016-2017 the proposed budget was $140 million.[273] From a business perspective, the Ponce municipal government is generally praised for its efficiency and speediness, thanks to its adoption of the Autonomous Municipality Law of 1991.[274]

The municipality of Ponce is the seat of the Puerto Rico Senatorial district V, which is represented by two senators. During the 2020 Puerto Rico Senate election, Marially González and Ramón Ruiz, both from the Popular Democratic Party, were elected as District Senators and are currently serving.[275]

Symbols

editThe municipio has an official flag and coat of arms.[276]

Coat of arms

editThe coat of arms of the municipality is based on the design of the official mayoral seal that was adopted in 1844 under the administration of mayor Salvador de Vives.[277]

The coat of arms of Ponce consists of an escutcheon (shield) in the Spanish tradition. This shield has a field with a party per bend division. The division runs from top left to bottom right. The field is red and black, bordered with a fine golden line. In the center of the shield is the figure of an erect lion standing on a bridge. The top of the bridge is a golden, the middle is red bricks, and the base foundation is gray rocks. Under the bridge there are gray wavy lines. Over the shield rests a five-tower golden stone wall with openings in the form of red windows. To the left of the shield is a coffee tree branch with its fruit, and to the right of the shield is a sugarcane stalk. The symbols of the shield are as follows: The field represents the flag of the municipality of Ponce, divided diagonally in the traditional city colors: red and black. The lion over the bridge alludes to the last name of the conqueror and first governor of Puerto Rico, Juan Ponce de Leon. The waves under the bridge allude to the Rio Portugues, on the banks of which the city was born. The coronet in the form of a five-tower mural crown above the shield allude to the Spanish crown, through which the settlement obtained its city charter. The coffee tree branch and the sugarcane stalk represent the main agricultural basis of the economy of the young municipality.[277]

Flag

editPonce has two official flags, one for the municipality and one for the city proper. The municipal flag, "the 1692 flag", was adopted in 1967 via a municipal ordinance. This flag, designed by Mario Ramirez, was selected from among a number of public proposals. It consisted of a rectangular cloth divided by a diagonal line into two equal isosceles triangles. The line ran from the top right-hand corner to the bottom left-hand corner. The top triangle was black; the bottom right triangle was red. On the top triangle was the figure of a lion over a bridge. On the bottom triangle was the word "Ponce" with the number "1692", the date when the municipality was founded. Ponce Municipal Assembly Order No. 5, Section 5, of Municipal Assembly Year 1966-1967 established that the last Sunday in April is "Día de la Bandera de Ponce" (Ponce Flag Day).[278]

Ten years later, in 1977, a new municipal ordinance introduced a flag, "the 1877 city flag" to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the declaration of the city charter. This (1977) flag consisted of a rectangular cloth divided by a diagonal line, creating two equal isosceles triangles, starting from the top left hand corner and ending on the lower right hand corner. The top triangle is red; the bottom triangle is black. In the center of the flag sits the shield of the municipality. Under this shield is the number "1877", the year of the founding of the city, and above the shield is the word "PONCE". Some flags have the "1877" date on the left border of the bottom triangle and the name of the city on the right border of the triangle, as illustrated in the insert on the left.[279]

Municipal services

editFire protection

editThe city's fire department has a history of firsts, including being the first organized fire department in the Island. As the largest city in the island at the time, and de facto economic and social center of Puerto Rico, this in effect also created the first Puerto Rico Fire Department. The Ponce Fire Department also built the first fire station in the Island,[280][281] which still stands to this day, and is now open as the Parque de Bombas museum. Also, in 1951, Ponce's Fire Chief Raúl Gándara Cartagena, wrote a book on the firemen's service, which became a firemen's manual in several Latin American countries.[282] In recognition of the service rendered by its fire fighters, the City of Ponce built them homes resulting in the creation of the 25 de Enero Street near the city's historic district.

Major fires

editThe city has withstood some nearly catastrophic fires.

A major fire took place on February 27, 1820,[283][284] that "almost destroyed the early Ponce settlement". It destroyed 106 "of the best homes in town."[285] In 1823, then Governor of Puerto Rico, Miguel de la Torre mandated that "every male from 16 to 60 years old must be a firefighter".[286] Those firefighters had to supply their own fire fighting equipment (essentially picks, buckets, and shovels). Once De la Torre left office, this first fire fighting institution started to decay.[286]

Another major fire occurred in La Playa in March 1845,[285] that destroyed "most of the Ponce vicinity." It significantly damaged the Spanish Customs House in Ponce, this being one of the few buildings left standing after the fire.[287] The fire burned down the major buildings of the "Marina de Ponce".[285] After this fire, then governor of Puerto Rico Conde de Mirasol (born Rafael de Aristegui y Velez),[288] created a new fire fighting organization staffed by volunteers.[286] In 1862, the Ponce Firefighters Corps was reorganized under the administration of Ponce mayor Luis de Quixano y Font, and Tomás Cladellas was named fire chief.[286] In 1879 the Ponce Fire Corps reorganized again, with a new fire chief, the local architect Juan Bertoli.

On September 25, 1880 another fire, took place destroying most of the older civil records (births, baptisms, marriages, etc.) of the Ponce parish.[289] In 1883, the Ponce firefighter corps reorganized once more, this time in a more definitive fashion when Máximo Meana was mayor of Ponce. During this time the Ponce Fire Corps was made up of 400 firefighters. Its leadership consisted of Julio Steinacher, fire chief, Juan Seix, second fire chief, Oscar Schuch Olivero, Chief of Brigade, and Fernando M. Toro, Supervisor of the Gymnastics Academy. Concurrent with this, the firefighter corps music band was organized. In September 1883, Juan Morel Campos formally organized the Ponce Fire Corps Municipal Band which exists to this day.[286]

The fourth Ponce fire of large proportions occurred on January 25, 1899.[290] The fire was fought by a group of firefighters among whom was Pedro Sabater and the civilian Rafael Rivera Esbrí, who would later become mayor of the city. The fire started at the U.S. munitions depot on the lot currently occupied by the Ponce High School building and grounds. The heroes in that fire, believed to have saved the city from certain annihilation, are remembered to this day with monuments on their tombs as well as in a monument in the city square Plaza Las Delicias.[286] As a further gesture of gratitude, a neighborhood of distinctive Victorian-style cottages were constructed to house the firefighters and their families. These houses, painted in the red and black colors of the city, are located along a street named Calle 25 de Enero (25 de Enero street); they are still owned and occupied by the descendants of these firefighters and are a scenic attraction in Ponce's historic center.

Police

editThe Ponce Municipal Police consists of a force of some 500 officers.[291] This force is complemented by the Puerto Rico Police force. The Ponce Municipal Police has its headquarters at the southwest corner of the intersection of PR-163 (Las Americas Avenue) and PR-2R (Carretera Pámpanos). In addition it has three precincts as follows: Cantera, La Guancha, and Coto Laurel, plus specialized units at Port of the Americas (maritime unit), Mariani (transit unit), Belgica (motorcycle unit), and Parque Dora Clavell (tourism unit).

The Puerto Rico Police had its Ponce area regional headquarters from 1970 until 2011 on Hostos Avenue.[292] In 2011 it moved its command center to a new and larger facility further west on Urbanizacion Los Caobos in Barrio Bucana. It commands five precincts in the city: Villa, Playa, Morel Campos, La Rambla, and El Tuque. The Ponce municipal coverage of the Puerto Rico Police force is as follows:

- The Villa precinct covers barrios Primero, Segundo, Tercero, Cuarto, Quinto, and Sexto, and Portugués Urbano. This precinct includes the historic Ponce district.

- The Playa precinct (# 258[293]) covers the barrios of Playa, Capitanejo, Bucaná, and Vayas.

- The La Rambla precinct covers barrios Anón, Real, Maragüez, Cerrillos, Coto Laurel, Sabanetas, San Patricio, Monte Llano, Machuelo Arriba, Machuelo Abajo, and Portugués.

- The El Tuque precinct covers barrios Canas and Canas Urbano.

- The Morel Campos precinct covers barrios Guaraguao, Marueño, Tibes, Magueyes, Magueyes Urbano, and Quebrada Limón.

Crime

editIn 2002, most of the homicides in Puerto Rico were occurring in San Juan and the greater metropolitan areas of Bayamón, Carolina and Caguas, but Ponce also had a high homicide rate. Also in 2002, Puerto Rico law enforcement officials drafted plans to increase the number of forensic investigators by 25%. The investigators, assigned to the Institute of Forensic Sciences in San Juan, covered homicides in about 65 percent of the island, but the Institute was considering assigning Ponce its own unit.[294] By mid-year 2005, there had been 25 more murder cases in Ponce than for all of 2004, a significant increase.[295]

The police acknowledged that most crime cases in Puerto Rico are linked to drug-trafficking and illegal weapons. In mid-July 2005, Gov. Aníbal Acevedo Vilá announced a series of measures aimed at lowering Ponce's high murder rate. Some of those measures included the permanent transfer of 100 agents to the area, the appointment of a ballistics expert from the Institute of Forensic Sciences and of two prosecutors for the Department of Justice in Ponce. Puerto Rico Police Superintendent Pedro Toledo admitted that more than 100 agents are actually needed in the Ponce region in 2005, but that "there would be no additional transfers at the moment to avoid affecting other police areas."[295]

Ponce is a convenient transition point for drug smugglers due to its location on the Caribbean Sea and its proximity to Colombia and Venezuela.[296] From there packages are then transported to the United States by various means including the United States Postal Service.[296] The city is included in the area's HIDTA region.[296]

As most of the crime in Ponce is connected to the drug-trade, police have an eye on illegal smuggling through the Port of Ponce[297] A 2008 government report stated that, "Drug smuggling in containerized cargo is a significant maritime threat to the HIDTA (High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area) region. The vast and increasing quantity of goods transshipped through the region every year provides drug traffickers with ample opportunity to smuggle illicit drugs into, through, and from the area.[296] In July 2005, local police scored some points in their fight against drug-trafficking.[298]

By 2007, Ponce had experienced a 61% decline in the rate of violent crimes (Type I).[299] In 2010, there was a further reduction of 12 percent in violent crimes over 2009 statistics.[300] In August 2013, the Ponce Area Police Region, which includes Ponce and seven other adjacent municipalities, registered 27 fewer Type I crimes that it had by the same period in 2012.[301]

For the Ponce MSA, which includes the city of Ponce, its nineteen surrounding municipal barrios, the municipality of Juana Diaz, and the municipality of Villalba, crime data was tabulated in 2002 (Total MSA Population: 364,849). No data is available for the city or for the municipality of Ponce alone. The following statistics are registered:

| Category | Number | Rate per 100,000 |

|---|---|---|

| Violent crime^ | 929 | 254.6 |

| Property crime^^ | 5,938 | 1,627.5 |

| Murder and NNMS^^^ | 83 | 22.7 |

| Forcible rape | 25 | 6.9 |

| Robbery | 525 | 143.9 |

| Aggravated assault | 296 | 81.1 |

| Burglary | 1,588 | 435.2 |

| Larceny-theft | 3,803 | 1,042.3 |

| Motor vehicle theft | 547 | 149.9 |

Notes:

^ Violent crimes include: murder, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault.

^^ Property crimes include: burglary, larceny-theft, and motor vehicle theft.

^^^ NNMS, non-negligent manslaughter

Source: FBI[302]

FBI satellite office

editEducation

editGrade schools and high schools

editPonce's first school for boys was established in 1820.[304] Today there are over a hundred public and private schools.[305] As with the rest of Puerto Rico, public education in Ponce is handled by the Puerto Rico Department of Education. However, the local government is taking on a greater role in public education. On June 13, 2010, the mayor of Ponce announced the creation of a Municipal Education System and a School Board with the objective of obtaining accreditation for what would be the first free bilingual school in the city.[293]

Colleges and universities

editThere are also several colleges and universities located in the city, offering higher education, including professional degrees in architecture, medicine, law, and pharmacy. Some of these are:

- Caribbean University - Ponce

- Colegio Universitario Tecnologico de Ponce[306]

- Interamerican University of Puerto Rico at Ponce

- Ponce School of Medicine

- Pontifical Catholic University of Puerto Rico

- Universidad Ana G. Méndez - Ponce

- University of Puerto Rico at Ponce

There are also several other technical institutions like the Instituto de Banca y Comercio, Trinity College,[307] and the Ponce Paramedical College.

Nova Southeastern University, based in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, has a School of Pharmacy campus in Ponce.[308]

Health care

editThe city is served by several clinics and hospitals. There are four comprehensive care hospitals: Hospital Dr. Pila, Hospital San Cristobal, Hospital San Lucas,[309] and Hospital de Damas. In addition, Hospital Oncológico Andrés Grillasca specializes in the treatment of cancer,[310] and Hospital Siquiátrico specializes in mental disorders.[311] There is also a U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Outpatient Clinic that provides health services to U.S. veterans.[312] The U.S. Veterans Administration will build a new hospital in the city to satisfy regional needs.[313] In 2009, Hospital Damas was listed in the U.S. News & World Report as one of the best hospitals under the U.S. flag.[314] Ponce has the highest concentration of medical infrastructure per inhabitant of any municipality in Puerto Rico.

Transportation

editDue to its commercial and industrial significance, Ponce has consistently been a hub of transportation to the rest of the island.

Puerto Rico Highway 52 provides access to Salinas, Caguas, and San Juan. PR-2 grants access to southwestern and western municipalities as a full-access freeway. The PR-10 highway, which is still under construction as a faster alternative to PR-123, provides access to the interior of the island as well as points north of the island, such as Arecibo. PR-1 provides access to various points east and southeast of Puerto Rico, while PR-14 provides access to Coamo and other points in the central mountain region. PR-132 grants country-side access to the town of Peñuelas. PR-123 is the old road to Adjuntas and, while treacherous, it does provide an appreciation for countryside living in some of the municipality's barrios, such as Magueyes and Guaraguao.[315][316]

The city is served by a network of local highways and freeways. Running entirely within the municipal limits are PR-12, PR-9, PR-133, and PR-163 and a few others. Freeway PR-12 runs northbound starting at the Port of Ponce to connect with PR-14 on the northeastern part of the city. PR-9, also known as the Circuito de Circumnavegación de Ponce (Ponce's Circumferential Highway), is a highway still partly under construction. It runs mostly north of the city and connects PR-52 to PR-10 in an east-to-west fashion; when completed it will run as a beltway around most of the eastern and northern sections of the city.[317] PR-133 (Calle Comercio) connects PR-2 in west Ponce to PR-132. It is an extension of PR-1 from its PR-2 terminus into the city center. PR-163 crosses the City east-to-west connecting PR-52 and PR-14.[318][319][320][321] The municipality has 115 bridges.[322]

Ponce's public transportation system consists of taxicabs and share taxi service providing public cars and vans known as públicos[323] and a bus-based mass transit system.[324] There are five taxi companies in the city.[325] Most públicos depart from the terminal hub located in downtown Ponce, the Terminal de Carros Públicos Carlos Garay.[326][327] During the 1990s and 2000s, there was also a trolley system reminiscent of the one the city used in the 19th century and which traveled through the downtown streets, and which was used mostly by tourists.[328] Today it is used mostly during special events. There is also a small train that can bring tourists from the historic downtown area to the Paseo Tablado La Guancha on the southern shore,[329] As with the trolley, today the train is used mostly during special events. A ferry provides service to Isla de Caja de Muertos.[330] The new intra-city mass transit system, SITRAS, was scheduled to start operating in November 2011,[331] and, after a 3-month delay, the $4 million SITRAS system, was launched with 11 buses and three routes in February 2012.[324] A fourth route was to be added for the El Tuque sector according to a June 30, 2012 news report.[332]

Mercedita Airport sits 3 miles (4.8 km) east of downtown Ponce and handles both intra-island and international flights. The airport, used to be a private airfield belonging to Destilería Serralles rum distillery before it became a commercial airport serving the Ponce area in the 1940s. There is daily commercial non-stop air service to points in the United States.[333]

Since 1804, Ponce already boasted its own port facilities for large cargo ships.[334] The Port of Ponce is Puerto Rico's chief Caribbean port.[335] It is known as the Port of the Americas and is under expansion to convert it into a major international shipping hub.[336] It receives both cargo as well as passenger cruise ships.[337][338] A short-haul freight railroad also operates within the Port facilities.[339]

Notable Ponceños

editInternational relations

editThe Dominican Republic maintains a consular office in the city.[340]

Twin towns – sister cities

editPonce is twinned with:

Commemorative dates