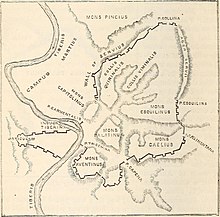

The Porta Fontinalis was a gate in the Servian Wall in ancient Rome. It was located on the northern slope of the Capitoline Hill, probably the northeast shoulder over the Clivus Argentarius.[1] The Via Salaria exited through it, as did the Via Flaminia originally, providing a direct link with Picene and Gallic territory.[2] After the Aurelian Walls were constructed toward the end of the 3rd century AD, the section of the Via Flaminia that ran between the Porta Fontinalis and the new Porta Flaminia was called the Via Lata ("Broadway").[3]

History

editDuring a highly active period of building construction and religious dedications following the Second Punic War, the aediles of 193 BC, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus and Lucius Aemilius Paullus, built a monumental portico linking the Porta Fontinalis to the Altar of Mars in the Campus Martius.[4] The portico, known as the Aemiliana, was a covered walkway for the censors, who conducted the census at the Altar of Mars but had their office just inside the gate, within the walls.[5]

The extant Tomb of Bibulus, dating to the first half of the 1st century BC, was located just outside the gate.[6] A funerary stele of the 2nd century AD preserves the name of a shoemaker, Gaius Julius Helius, who was located somewhere around the gate.[7] Most notoriously, Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso, the supposed poisoner of the Emperor Tiberius' heir apparent Germanicus, had built structures above the gate to connect his private residences. The resulting domus was criticized for dominating the architectural profile of the site. As part of the punitive measures against the associates, family, and memory of Piso in the wake of the conspiracy, the senate ordered the demolition of these structures.[8]

The Porta Fontinalis got its name from nearby springs (fontes),[9] such as the spring still in evidence in the lowest level of the Tullianum.[10] It may have had a religious connection to the god of springs and wells known as Fons or Fontus who was celebrated at the Fontinalia.[11]

Ancient sources that mention the gate include Livy and Paulus.[12]

References

edit- ^ Lawrence Richardson, A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), p. 311.

- ^ Romolo Augusto Staccioli, The Roads of the Romans («L'Erma» di Bretschneider, 2003), pp. 38, 72; Stephen L. Dyson, Rome: A Living Portrait of an Ancient City (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010), p. 42.

- ^ Staccioli, The Roads of the Romans, p. 17.

- ^ Livy 35.10.12; John E. Stambaugh, The Ancient Roman City (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988), p. 32; Daniel J. Gargola, Lands, Laws, and Gods: Magistrates and Ceremonies in the Regulation of Public Lands in Republican Rome (University of North Carolina Press, 1995), p. 135; Richardson, Topographical Dictionary, p. 303.

- ^ Richardson, Topographical Dictionary, pp. 41, 303.

- ^ Amanda Claridge, Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide (Oxford University Press, 1998), p. 168.

- ^ CIL 6.33914; Lauren Hackworth Petersen, "'Clothes Makes the Man': Dressing the Roman Freedman Body," in Bodies and Boundaries in Graeco-Roman Antiquity (de Gruyter, 2009), p. 182.

- ^ Tacitus, Annales 3.9.3; Greg Rowe, Princes and Political Cultures: The New Tiberian Senatorial Decrees (University of Michigan Press, 2002), p. 15; O.F. Robinson, Penal Practice and Penal Policy in Ancient Rome (Routledge, 2007), p. 72; Werner Eck, "Emperor and Senatorial Aristocracy in Competition for Public Space," in The Emperor and Rome: Space, Representation, and Ritual (Cambridge University Press, 2010), p. 103.

- ^ Harry B. Evans, Water Distribution in Ancient Rome (University of Michigan, 1994, 1997), p. 77; Richardson, Topographical Dictionary, p. 303.

- ^ Richardson, Topographical Dictionary, p. 71.

- ^ William Warde Fowler, The Roman Festivals of the Period of the Republic (London, 1908), p. 240.

- ^ Livy 35.10.11–12; Paulus ex Festo 75 in the edition of Lindsay; Richardson, Topographical Dictionary, p. 303.