Selected articles

The Western Mexico shaft tomb tradition or shaft tomb culture refers to a set of interlocked cultural traits found in the western Mexican states of Jalisco, Nayarit, and, to a lesser extent, Colima to its south, roughly dating to the period between 300 BCE and 400 CE, although there is not wide agreement on this end-date. Nearly all of the artifacts associated with this shaft tomb tradition have been discovered by looters and are without provenance, making dating problematic. The first major undisturbed shaft tomb associated with the tradition was not discovered until 1993, at Huitzilapa, Jalisco.

Originally regarded as of Tarascan origin, contemporary with the Aztecs, it became apparent in the middle of the 20th century, as a result of further research, that the artifacts and tombs were instead over 1000 years older. Until recently, the looted artifacts were all that was known of the people and culture or cultures that created the shaft tombs. So little was known, in fact, that a major 1998 exhibition highlighting these artifacts was subtitled: "Art and Archaeology of the Unknown Past".

It is now thought that, although shaft tombs are widely diffused across the area, the region was not a unified cultural area. Archaeologists, however, still struggle with identifying and naming the ancient western Mexico cultures of this period.

The Spanish conquest of Guatemala was a conflict that formed a part of the Spanish colonization of the Americas within the territory of what became the modern country of Guatemala in Central America. Before the conquest, this territory contained a number of competing Mesoamerican kingdoms, the majority of which were Maya. Many conquistadors viewed the Maya as "infidels" who needed to be forcefully converted and pacified, disregarding the achievements of their civilization. The first contact between the Maya and European explorers came in the early 16th century when a Spanish ship sailing from Panama to Santo Domingo was wrecked on the east coast of the Yucatán Peninsula in 1511. Several Spanish expeditions followed in 1517 and 1519, making landfall on various parts of the Yucatán coast. The Spanish conquest of the Maya was a prolonged affair; the Maya kingdoms resisted integration into the Spanish Empire with such tenacity that their defeat took almost two centuries.

Pedro de Alvarado arrived in Guatemala from the newly-conquered Mexico in early 1524, commanding a mixed force of Spanish conquistadors and native allies, mostly from Tlaxcala and Cholula. Placenames across Guatemala bear Nahuatl placenames owing to the influence of these Mexican allies, who translated for the Spanish. The Kaqchikel Maya initially allied themselves with the Spanish, but soon rebelled against excessive demands for tribute and did not finally surrender until 1530. In the meantime the other major highland Maya kingdoms had each been defeated in turn by the Spanish and allied warriors from Mexico and already subjugated Maya kingdoms in Guatemala. The Itza Maya and other lowland groups in the Petén Basin were first contacted by Hernán Cortés in 1525, but remained independent and hostile to the encroaching Spanish until 1697, when a concerted Spanish assault finally defeated the last independent Maya kingdom.

Spanish and native tactics and technology differed greatly. The Spanish viewed the taking of prisoners as a hindrance to outright victory, whereas the Maya prioritised the capture of live prisoners and of booty. The indigenous peoples of Guatemala lacked key elements of Old World technology such as a functional wheel, horses, steel and gunpowder; they were also extremely susceptible to Old World diseases, against which they had no resistance. The Maya preferred raiding and ambush to large-scale warfare, using spears, arrows and wooden swords with inset obsidian blades; the Xinca of the southern coastal plain used poison on their arrows. In response to the use of Spanish cavalry, the highland Maya took to digging pits and lining them with wooden stakes.

The Mesoamerican ballgame or ōllamaliztli (hispanized as Ulama) in Nahuatl was a sport with ritual associations played since 1,400 B.C. by the pre-Columbian peoples of Ancient Mexico and Central America. The sport had different versions in different places during the millennia, and a modern version of the game, ulama, is still played in a few places by the local indigenous population.

The rules of the ballgame are not known, but judging from its descendant, ulama, they were probably similar to racquetball, where the aim is to keep the ball in play. The stone ballcourt goals (see photo to right) are a late addition to the game.

In the most widespread version of the game, the players struck the ball with their hips, although some versions allowed the use of forearms, rackets, bats, or handstones. The ball was made of solid rubber and weighed as much as 4 kg (9 lbs), and sizes differed greatly over time or according to the version played.

The game had important ritual aspects, and major formal ballgames were held as ritual events, often featuring human sacrifice. The sport was also played casually for recreation by children and perhaps even women.

Pre-Columbian ballcourts have been found throughout Mesoamerica, as far south as Nicaragua, and possibly as far north as the now U.S. state of Arizona. These ballcourts vary considerably in size, but all have long narrow alleys with side-walls against which the balls could bounce.

Maya stelae (singular stela) are monuments that were fashioned by the Maya civilization of ancient Mesoamerica. They consist of tall sculpted stone shafts and are often associated with low circular stones referred to as altars, although their actual function is uncertain. Many stelae were sculpted in low relief, although plain monuments are found throughout the Maya region. The sculpting of these monuments spread throughout the Maya area during the Classic Period (250–900 AD), and these pairings of sculpted stelae and circular altars are considered a hallmark of Classic Maya civilization. The earliest dated stela to have been found in situ in the Maya lowlands was recovered from the great city of Tikal in Guatemala. During the Classic Period almost every Maya kingdom in the southern lowlands raised stelae in its ceremonial centre.

Stelae became closely associated with the concept of divine kingship and declined at the same time as this institution. The production of stelae by the Maya had its origin around 400 BC and continued through to the end of the Classic Period, around 900, although some monuments were reused in the Postclassic (c. 900–1521). The major city of Calakmul in Mexico raised the greatest number of stelae known from any Maya city, at least 166, although they are very poorly preserved.

Hundreds of stelae have been recorded in the Maya region, displaying a wide stylistic variation. Many are upright slabs of limestone sculpted on one or more faces, with available surfaces sculpted with figures carved in relief and with hieroglyphic text. Stelae in a few sites display a much more three dimensional appearance where locally available stone permits, such as at Copán and Toniná. Plain stelae do not appear to have been painted nor overlaid with stucco decoration, but most Maya stelae were probably brightly painted in red, yellow, black, blue and other colours.

Nahuatl (Nahuatl pronunciation: [ˈnaːwatɬ] , with stress on the first syllable) is a group of related languages and dialects of the Nahuan (traditionally called "Aztecan") branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Altogether they are spoken by an estimated 1.5 million Nahua people, most of whom live in central Mexico. All Nahuan languages are indigenous to Mesoamerica.

Nahuatl has been spoken in central Mexico since at least the 7th century AD. It was the language of the Aztecs, who dominated what is now central Mexico during the Late Postclassic period of Mesoamerican chronology. During the preceding century and a half, the expansion and influence of the Aztec Empire had led to the variety spoken by the residents of Tenochtitlan becoming a prestige language in Mesoamerica. With the introduction of the Latin alphabet, Nahuatl also became a literary language and many chronicles, grammars, works of poetry, administrative documents and codices were written in the 16th and 17th centuries. This early literary language based on the Tenochtitlan variety has been labeled Classical Nahuatl and is among the most studied and best documented languages of the Americas.

Today Nahuatl varieties are spoken in scattered communities mostly in rural areas. There are considerable differences among varieties, and some are mutually unintelligible. They have all been subject to varying degrees of influence from Spanish. No modern Nahuatl languages are identical to Classical Nahuatl, but those spoken in and around the Valley of Mexico are generally more closely related to it than those on the periphery. Under Mexico's Ley General de Derechos Lingüísticos de los Pueblos Indígenas ("General Law on the Linguistic Rights of Indigenous Peoples") promulgated in 2003, Nahuatl along with the other indigenous languages of Mexico are recognized as lenguas nacionales ("national languages") in the regions where they are spoken, enjoying the same status as Spanish within their region.

The Mayan languages (alternatively: Maya languages) form a language family spoken in Mesoamerica and northern Central America. Mayan languages are spoken by at least 6 million indigenous Maya, primarily in Guatemala, Mexico, Belize and Honduras. In 1996, Guatemala formally recognized 21 Mayan languages by name, and Mexico recognizes eight more.

The Mayan language family is one of the best documented and most studied in the Americas. Modern Mayan languages descend from Proto-Mayan, a language thought to have been spoken at least 5,000 years ago; it has been partially reconstructed using the comparative method.

Mayan languages form part of the Mesoamerican Linguistic Area, an area of linguistic convergence developed throughout millennia of interaction between the peoples of Mesoamerica. All Mayan languages display the basic diagnostic traits of this linguistic area. For example, all use relational nouns instead of prepositions to indicate spatial relationships. They also possess grammatical and typological features that set them apart from other languages of Mesoamerica, such as the use of ergativity in the grammatical treatment of verbs and their subjects and objects, specific inflectional categories on verbs, and a special word class of "positionals" which is typical of all Mayan languages.

During the pre-Columbian era of Mesoamerican history, some Mayan languages were written in the Maya hieroglyphic script. Its use was particularly widespread during the Classic period of Maya civilization (c. 250–900 CE). The surviving corpus of over 10,000 known individual Maya inscriptions on buildings, monuments, pottery and bark-paper codices, combined with the rich postcolonial literature in Mayan languages written in the Latin script, provides a basis for the modern understanding of pre-Columbian history unparalleled in the Americas.

The most important staple of Aztec cuisine was maize (corn), a crop that was so important to Aztec society that it played a central part in their mythology. Just like wheat in Europe or rice in most of East Asia, it was the food without which a meal was not a meal. It came in an inestimable number of varieties varying in color, texture, size and prestige and was eaten as tortillas, tamales or atolli, maize gruel. The other constants of Aztec food were salt and chili peppers and the basic definition of Aztec fasting was to abstain from these two flavorers. The other major foods were beans and New World varieties of the grains amaranth (or pigweed), and chia. The combination of maize and these basic foods would have provided the average Aztec with a very well-rounded diet without any significant deficiencies in vitamins or minerals. The processing of maize called nixtamalization, the cooking of maize grains in alkaline solutions, also drastically increased the nutritional value of the common staple.

Water, maize gruels and pulque, the fermented juice of the century plant, were the most common drinks, and there were many different fermented alcoholic beverages made from honey, cacti and various fruits. The elite took pride in not drinking pulque, a drink of commoners, and preferred drinks made from cacao. It was one of the most prestigious luxuries available; it was the drink of rulers, warriors and nobles and was flavored with chili peppers, honey and a seemingly endless list of spices and herbs.

The Aztec diet included an impressive variety of animals; turkeys and various fowl, pocket gophers, Green iguanas, axolotls (a type of water salamander), shrimp, fish and a great variety of insects, larvae and insect eggs. They ate various mushrooms and fungi, including the parasitic corn smut, which grows on ears of corn. Squash was very popular and came in many different varieties. Squash seed, fresh, dried or roasted, were especially popular. Tomatoes, though different from the varieties common today, was often mixed with chili in sauces or as filling for tamales.

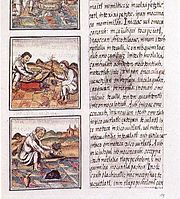

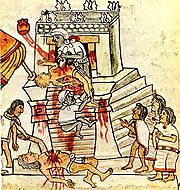

Human sacrifice was a religious practice characteristic of pre-Columbian Aztec civilization; the extent of the practice is debated by modern scholars. Spanish explorers, soldiers and clergy who had contact with the Aztecs between 1517, when an expedition from Cuba first explored the Yucatan, and 1521, when Hernan Cortes conquered the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, made observations of and wrote reports about the practice of human sacrifice. For example, Bernal Díaz's The Conquest of New Spain includes eyewitness accounts of human sacrifices as well as descriptions of the remains of sacrificial victims. In addition, there are a number of second-hand accounts of human sacrifices written by Spanish friars that relate the testimony of native eyewitnesses. The literary accounts have been supported by archeological research. Since the late 1970s, excavations of the offerings in the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan, Teotihuacán's Pyramid of the Moon, and other archaeological sites, have provided physical evidence of human sacrifice among the Mesoamerican peoples.

Human sacrifice among pre-Columbian indigenous populations is a controversial topic. The discussion of human sacrifice is connected with the classic conflict between viewing indigenous peoples as either "noble savages" or "primitive barbarians." Within modern scholarship, some scholars tend to romanticize the description of human sacrifice while others tend to exaggerate it.

Xochimilco (Spanish IPA: [ʃotʃiˈmilko]) is one of the sixteen delegaciones or boroughs within Mexican Federal District. The borough is centered on the formerly independent city of Xochimilco, which was established on what was the southern shore of Lake Xochimilco in the pre-Hispanic period. Today, the borough consists of the eighteen “barrios” or neighborhoods of this city along with fourteen “pueblos” or villages that surround it, covering an area of 125 km2 (48 sq mi). While the borough is somewhat in the geographic center of the Federal District, it is considered to be “south” and has an identity separate from the historic center of Mexico City. This is due to its historic separation from that city during most of its history. Xochimilco is best known for its canals, which are left from what was an extensive lake and canal system which connected most of the settlements of the Valley of Mexico. These canals, along with artificial islands called chinampas attract tourists and other city residents to ride on colorful gondola like boats called “trajineras” around the 170 km (110 mi) of canals. This canal and chinampa system, as a vestige of the area’s pre-Hispanic past, has made Xochimilco a World Heritage Site; however, environmental degradation of both the canals and the chinampas is severe and ongoing, putting that status in question for the future.

Mesoamerican languages are the languages indigenous to the Mesoamerican cultural area, which covers southern Mexico, all of Guatemala and Belize and parts of Honduras and El Salvador. The area is characterized by extensive linguistic diversity containing several hundred different languages and seven major language families. Mesoamerica is also an area of high linguistic diffusion in that long-term interaction among speakers of different languages through several millennia has resulted in the convergence of certain linguistic traits across disparate language families. The Mesoamerican sprachbund is commonly referred to as the Mesoamerican Linguistic Area.

The languages of Mesoamerica were also among the first to evolve independent traditions of writing. The oldest texts date to approximately 1000 B.C.E. while most texts in the indigenous scripts (such as Maya) date to ca. 600–900 CE. Following the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century, and continuing up until the 19th century, most Mesoamerican languages were written in Latin script.

El Tajín is a pre-Columbian archeological site and one of the largest and most important cities of the Classic era of Mesoamerica. A part of the Classic Veracruz culture, El Tajín flourished from 600 to 1200 C.E. and during this time numerous temples, palaces, ballcourts, and pyramids were built. From the time the city fell in 1230 to near the end of the 18th century, no European seems to have known of its existence, until a government inspector chanced upon the Pyramid of the Niches in 1785.

El Tajín was named a World Heritage site in 1992, due to its cultural importance and its architecture. This architecture includes the use of decorative niches and cement in forms unknown in the rest of Mesoamerica. Its best-known monument is the Pyramid of the Niches, but other important monuments include the Arroyo Group, the North and South Ballcourts and the palaces of Tajín Chico. In total there have been 17 ballcourts discovered at this site. Since the 1970s, El Tajin has been the most important archeological site in Veracruz for tourists, attracting over 650,000 visitors a year.

Tak'alik Ab'aj (/tɑːkəˈliːk əˈbɑː/; Mayan pronunciation: [takʼaˈlik aˈɓaχ] ; Spanish: [takaˈlik aˈβax]) is a pre-Columbian archaeological site in Guatemala; it was formerly known as Abaj Takalik; its ancient name may have been Kooja. It is one of several Mesoamerican sites with both Olmec and Maya features. The site flourished in the Preclassic and Classic periods, from the 9th century BC through to at least the 10th century AD, and was an important centre of commerce, trading with Kaminaljuyu and Chocolá. Investigations have revealed that it is one of the largest sites with sculptured monuments on the Pacific coastal plain. Olmec-style sculptures include a possible colossal head, petroglyphs and others. The site has one of the greatest concentrations of Olmec-style sculpture outside of the Gulf of Mexico.

Takalik Abaj is representative of the first blossoming of Maya culture that had occurred by about 400 BC. The site includes a Maya royal tomb and examples of Maya hieroglyphic inscriptions that are among the earliest from the Maya region. Excavation is continuing at the site; the monumental architecture and persistent tradition of sculpture in a variety of styles suggest the site was of some importance.

Takalik Abaj was a sizeable city with the principal architecture clustered into four main groups spread across nine terraces. While some of these were natural features, others were artificial constructions requiring an enormous investment in labour and materials. The site featured a sophisticated water drainage system and a wealth of sculptured monuments.

Olmec figurines are archetypical figurines that were produced by the Formative Period inhabitants of Mesoamerica. While many of these figurines may or may not have been produced directly by the people of the Olmec heartland, they bear the hallmarks and motifs of Olmec culture.

These figurines are usually found in household refuse, in ancient construction fill, and (outside the Olmec heartland) in graves, although many Olmec-style figurines, particularly those labelled as Las Bocas- or Xochipala-style, were recovered by looters and are therefore without provenance.

The vast majority of figurines are simple in design, often nude or with a minimum of clothing, and made of local terracotta. Most of these recoveries are mere fragments: a head, arm, torso, or a leg. It is thought, based on wooden busts recovered from the water-logged El Manati site, that figurines were also carved from wood, but, if so, none have survived.

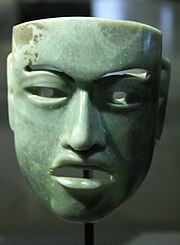

More durable and better known by the general public are those figurines carved, usually with a degree of skill, from jade, serpentine, greenstone, basalt, and other minerals and stones.

Copán is an archaeological site of the Maya civilization located in the Copán Department of western Honduras, not far from the border with Guatemala. It was the capital city of a major Classic period kingdom from the 5th to 9th centuries AD. The city was located in the extreme southeast of the Mesoamerican cultural region, on the frontier with the Isthmo-Colombian cultural region, and was almost surrounded by non-Maya peoples. In this fertile valley now lies a city of about 3000, a small airport, and a winding road.

Copán was occupied for more than two thousand years, from the Early Preclassic period right through to the Postclassic. The city developed a distinctive sculptural style within the tradition of the lowland Maya, perhaps to emphasize the Maya ethnicity of the city's rulers.

The city has a historical record that spans the greater part of the Classic period and has been reconstructed in detail by archaeologists and epigraphers. Copán, probably called Oxwitik by the Maya, was a powerful city ruling a vast kingdom within the southern Maya area. The city suffered a major political disaster in AD 738 when Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil, one of the greatest kings in Copán's dynastic history, was captured and executed by his former vassal, the king of Quiriguá. This unexpected defeat resulted in a 17-year hiatus at the city, during which time Copán may have been subject to Quiriguá in a reversal of fortunes.

Quelepa is an important archaeological site located in eastern El Salvador. The site was founded around 400 BC, in the Late Preclassic period (500 BC - AD 250). The inhabitants constructed a platform from plaster and pumice and rebuilt it a number of times. Artefacts recovered during the excavations of the site indicate that the local population depended upon subsistence agriculture, these artefacts included metates (a kind of mortar) and comales (a type of griddle). The site belonged to the Mesoamerican cultural region. Quelepa is generally considered to have been settled by the Lenca people. Quelepa means "stone jaguar" in the Lenca language, probably in reference to the large Jaguar Altar found at the site.

Throughout its occupational history, the inhabitants crafted stone tools from obsidian. The site appears to have been linked to trade routes to western El Salvador and the Guatemalan Highlands and also to the north in Honduras.

Although sites in western El Salvador were severely affected by the eruption of the Ilopango Volcano in the Early Classic, the only affect this had upon Quelepa was the cutting of trade routes into Mesoamerica. This did not result in stagnation at the site but rather resulted in the florescence of a local culture.

Olmec colossal heads are a distinctive feature of the Olmec civilization of ancient Mesoamerica. The first archaeological investigations of Olmec culture were carried out by Matthew Stirling at Tres Zapotes in 1938, owing to the discovery there of a colossal head in the 19th century. Seventeen confirmed examples of stone heads are known, all from within the Olmec heartland on the Gulf Coast of Mexico, in the states of Veracruz and Tabasco. Most colossal heads were sculpted from spherical boulders but two from San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán were recarved from massive stone thrones. An additional monument, at Takalik Abaj in Guatemala, is a throne that may have been carved from a colossal head. This is the only known example outside of the Olmec heartland.

Dating of the monuments has proven difficult due to the movement of many from their original context. Most of the heads have been dated to the Early Preclassic (1500-1000 BC) and some to the Middle Preclassic (1000-400 BC). The smallest examples weigh 6 tons, while the largest is variously estimated to weigh 40 to 50 tons, although this was abandoned unfinished near to its quarry.

Olmec colossal heads were sculpted from large basalt boulders quarried in the Sierra de los Tuxtlas mountains of Veracruz. They were transported over large distances, although the method used for transportation is not clear. Finished momuments represented lifelike portraits of individual Olmec rulers, each wearing a distinctive headdress, and heads were variously arranged in lines or groups at major Olmec centres.

Read more...

Qʼumarkaj, (Kʼicheʼ: [qʼumarˈkah]) is an archaeological site in the southwest of the El Quiché department of Guatemala. Qʼumarkaj is also known as Utatlán, the Nahuatl translation of the city's name. The name comes from Kʼicheʼ Qʼumarkah "Place of old reeds".

Qʼumarkaj was one of the most powerful Maya cities when the Spanish arrived in the region in the early 16th century. It was the capital of the K'iche' Maya in the Late Postclassic Period. Archaeologically and ethnohistorically, Qʼumarkaj is the best known of the Late Postclassic highland Maya capitals. The earliest reference to the site in Spanish occurs in Hernán Cortés' letters from Mexico. Although the site has been investigated, little reconstruction work has taken place. The surviving architecture, which includes a Mesoamerican ballcourt, temples and palaces, has been badly damaged by the looting of stone to build the nearby town of Santa Cruz del Quiché.

The major structures of Qʼumarkaj were laid out around a plaza. They included the temple of Tohil, a jaguar god who was patron of the city, the temple of Awilix, the patron goddess of one of the noble houses, the temple of Jakawitz, a mountain deity who was also a noble patron and the temple of Qʼuqʼumatz, the Feathered Serpent, the patron of the royal house. The main ballcourt was placed between the palaces of two of the principal noble houses. Palaces, or nimja, were spread throughout the city. There was also a platform that was used for gladiatorial sacrifice.

Santa Muerte (Spanish for Saint Death), is a female folk saint venerated primarily in Mexico and the United States. A personification of death, she is associated with healing, protection, and safe delivery to the afterlife by her devotees. Not sanctioned by the Roman Catholic Church, her cult arose from popular Mexican folk belief, a syncretism between indigenous Mesoamerican and Spanish Catholic beliefs and practices. Since the pre-Columbian era Mexican culture has maintained a certain reverence towards death, which can be seen in the widespread commemoration of the syncretic Day of the Dead. Elements of that celebration include the use of skeletons to remind people of their mortality. The worship is condemned by the Catholic Church in Mexico as invalid, but it is firmly entrenched among Mexico's lower working classes and various elements of society deemed as "outcasts".

Santa Muerte generally appears as a female skeletal figure, clad in a long robe and holding one or more objects, usually a scythe and a globe. Her robe can be of any color, as more specific images of the figure vary widely from devotee to devotee and according to the rite being performed or the petition being made. As the worship of Santa Muerte was clandestine until the 20th century, most prayers and other rites have been traditionally performed privately in the home. However, for the past ten years or so, worship has become more public, especially in Mexico City after Enriqueta Romero initiated her famous Mexico City shrine in 2001. The number of believers in Santa Muerte has grown over the past ten to twenty years, to several million followers in Mexico, the United States, and parts of Central America. Santa Muerte has similar male counterparts in the Americas, such as the skeletal folk saints San La Muerte of Argentina and Rey Pascual of Guatemala.

Chacmool (also spelled chac-mool) is the term used to refer to a particular form of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican sculpture depicting a reclining figure with its head facing 90 degrees from the front, supporting itself on its elbows and supporting a bowl or a disk upon its stomach. These figures possibly symbolised slain warriors carrying offerings to the gods; the bowl upon the chest was used to hold sacrificial offerings, including pulque, tamales, tortillas, tobacco, turkeys, feathers and incense. In an Aztec example the recipient is a cuauhxicalli (a stone bowl to receive sacrificed human hearts). Chacmools were often associated with sacrificial stones or thrones.

Aztec chacmools bore water imagery and were associated with Tlaloc, the rain god. Their symbolism placed them on the frontier between the physical and supernatural realms, as intermediaries with the gods. The chacmool form of sculpture first appeared around the 9th century AD in the Valley of Mexico and the northern Yucatán Peninsula.

The Olmec were the first major civilization in Mexico. They lived in the tropical lowlands of south-central Mexico, in the modern-day states of Veracruz and Tabasco.

The Olmec flourished during Mesoamerica's Formative period, dating roughly from as early as 1500 BCE to about 400 BCE. Pre-Olmec cultures had flourished in the area since about 2500 BCE, but by 1600–1500 BCE Early Olmec culture had emerged centered on the San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán site near the coast in southeast Veracruz. They were the first Mesoamerican civilization and laid many of the foundations for the civilizations that followed. Among other "firsts", the Olmec appeared to practice ritual bloodletting and played the Mesoamerican ballgame, hallmarks of nearly all subsequent Mesoamerican societies.

The most familiar aspect of the Olmecs is their artwork, particularly the aptly named "colossal heads". The Olmec civilization was first defined through artifacts which collectors purchased on the pre-Columbian art market in the late 19th century and early 20th century. Olmec artworks are considered among ancient America's most striking.

Mexican feather work, also called "plumería", was an important artistic and decorative technique in the pre-Hispanic and colonial periods in what is now Mexico. Although feathers have been prized and feather works created in other parts of the world, those done by the "amanteca" impressed Spanish conquerors, leading to a creative exchange with Europe. Feather pieces took on European motifs in Mexico. Feathers and feather works became prized in Europe. The "golden age" for this technique as an art form was from just before the Spanish conquest to about a century afterwards. At the beginning of the 17th century, it began a decline due to the death of the old masters, the disappearance of the birds that provide fine feathers and the depreciation of indigenous handiwork. Feather work, especially the creation of "mosaics" or "paintings" principally of religious images remained noted by Europeans until the 19th century, but by the 20th century, the little that remained has become a handcraft, despite efforts to revive it. Today, the most common feather objects are those made for traditional dance costumes although mosaics are made in the state of Michoacán, and feather trimmed huipils are made in the state of Chiapas.

The Maya civilization was a Mesoamerican civilization developed by the Maya peoples, noted for the Maya hieroglyphic script, the only known fully developed writing system of the pre-Columbian Americas, as well as for its art, architecture, and mathematical and astronomical systems. The Maya civilization developed in an area that encompasses southeastern Mexico, all of Guatemala and Belize, and the western portions of Honduras and El Salvador. This region consists of the northern lowlands encompassing the Yucatán Peninsula, and the highlands of the Sierra Madre, running from the Mexican state of Chiapas, across southern Guatemala and onwards into El Salvador, and the southern lowlands of the Pacific littoral plain.