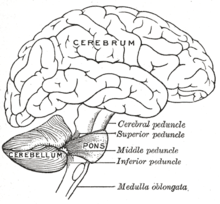

Post-viral cerebellar ataxia also known as acute cerebellitis and acute cerebellar ataxia (ACA) is a disease characterized by the sudden onset of ataxia following a viral infection.[1] The disease affects the function or structure of the cerebellum region in the brain.

| Post-viral cerebellar ataxia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cerebellum (Lower left) | |

| Specialty | Neurology, Infectious disease |

Symptoms and signs

editMost symptoms of people with post-viral cerebellar ataxia deal to a large extent with the movement of the body. Some common symptoms that are seen are clumsy body movements and eye movements, difficulty walking, nausea, vomiting, and headaches.[citation needed]

Causes

editPost-viral cerebellar ataxia is caused by damage to or problems with the cerebellum. It is most common in children, especially those younger than age 3, and usually occurs several weeks following a viral infection. Viral infections that may cause it include chickenpox, Coxsackie disease (also called hand-foot-and-mouth disease), Epstein–Barr virus (a common human virus that belongs to the herpes family), influenza,[2] HIV,[3] and SARS-CoV-2[4] [5] (the virus that causes COVID-19).

Diagnosis

editSince the majority of ACA cases result from a post-viral infection, the physician’s first question will be to ask if the patient has been recently ill. From this point a series of exclusion tests can determine if the current state of ataxia is a correct diagnosis or not. A CT (computed tomography) scan with normal results can rule out the possibility of the presence of a posterior fossa tumor and an acute hemorrhage, which would both have abnormal results. Other imaging tests like EEG (electroencephalographs) and MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) can also be performed to eliminate possible diagnoses of other severe diseases, such as neuroblastoma, drug intoxication, acute labyrinthitis, and metabolic diseases. A more complicated test that is performed for research analysis of the disease is to isolate viruses from the CSF (cerebrospinal fluid). This can show that the virus has attacked the nervous system of the patient and resulted in the ataxia symptoms.[citation needed]

Differential diagnosis

editDifferential diagnosis may include:[citation needed]

Treatment

editAtaxia usually goes away without any treatment. In cases where an underlying cause is identified, medical treatment may be needed. In extremely rare cases, patients can have continuing and disabling symptoms. Treatment includes corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, or plasma exchange therapy. Drug treatment to improve muscle coordination has a low success rate. However, the following drugs may be prescribed: clonazepam, amantadine, gabapentin, or buspirone. Occupational or physical therapy may also alleviate lack of coordination. Changes to diet and nutritional supplements may also help. Treatment will depend on the cause. If the ataxia is due to bleeding, surgery may be needed. For a stroke, medication to thin the blood can be given. Infections may need to be treated with antibiotics. Steroids may be needed for swelling (inflammation) of the cerebellum (such as from multiple sclerosis). Cerebellar ataxia caused by a recent viral infection may not need treatment.[citation needed]

Prognosis

editPeople whose condition was caused by a recent viral infection should make a full recovery without treatment in a few months. Fine motor skills, such as handwriting, typically have to be practised in order to restore them to their former ability. In more serious cases, strokes, bleeding or infections may sometimes cause permanent symptoms.[citation needed]

History

editWestphal reported the first documented case of post-viral cerebellar ataxia in 1872, where associations of reversible cerebellar syndrome were observed.[6] Another early case was documented in 1905. Batten described in detail cases of post-infectious cerebellar ataxia in five children. The cause of the disease was unknown until 1978 when Weiss and Guberman proposed that ACA could be due to direct invasion of the central nervous system by infectious agents. Since then many case studies have followed to understand the underlying conditions, symptoms and causes of the disease. The largest study of retrospective childhood ACA was done in 1994 by Connolly. This disease is still commonly used as a reference in clinical practice for other inflammatory and autoimmune disorders of the nervous system.[7]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Nussinovitch, Moshe; Prais, Dario; Volovitz, Benjamin; Shapiro, Rivka; Amir, Jacob (2003). "Post-Infectious Acute Cerebellar Ataxia in Children". Clinical Pediatrics. 42 (7): 581–4. doi:10.1177/000992280304200702. PMID 14552515. S2CID 22942874.

- ^ Mishra, Ritu; Banerjea, Akhil C. (10 September 2020). "Frontiers | Neurological Damage by Coronaviruses: A Catastrophe in the Queue! | Immunology". Frontiers in Immunology. 11: 565521. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.565521. PMC 7511585. PMID 33013930.

In the case of Influenza infections, there is an extensive history of patients reporting a variety of CNS disorders which collectively suggested that Influenza virus is a potentially neurotropic virus and is capable of giving long-lasting neurological sequelae (116). Even some recent outbreaks and the 2009 "Swine Flu" pandemic also gave similar indications that neurological consequences are a much likely after-effect of Influenza infection (120, 121). Although being notorious for respiratory disease outcomes, their second most common disease manifestations are encephalitis and other CNS complications such as ataxia, myelopathy, seizures, and delirium, which usually appear after 1 week of respiratory symptoms of influenza.

- ^ Bergquist, Jennifer (September 12, 2005). "Childhood Ataxia" (PDF). University of Chicago. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ Fadakar; et al. (2020). "A First Case of Acute Cerebellitis Associated with Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): a Case Report and Literature Review". The Cerebellum. 19 (6): 911–914. doi:10.1007/s12311-020-01177-9. PMC 7393247. PMID 32737799.

- ^ Khan; et al. (2021). "Clinical Spectrum of Neurological Manifestations in Pediatric COVID-19 Illness: A Case Series" (PDF). Journal of Tropical Pediatrics. 67 (3). doi:10.1093/tropej/fmab059. PMC 8344577. PMID 34247238. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ Hinchey, Judy; Chaves, Claudia; Appignani, Barbara; Breen, Joan; Pao, Linda; Wang, Annabel; Pessin, Michael S.; Lamy, Catherine; Mas, Jean-Louis; Caplan, Louis R. (1996). "A Reversible Posterior Leukoencephalopathy Syndrome". New England Journal of Medicine. 334 (8): 494–500. doi:10.1056/NEJM199602223340803. PMID 8559202.

- ^ Bae, Jong Seok; Kim, Byoung Joon (2005). "Cerebellar ataxia and acute motor axonal neuropathy associated with Anti GD1b and Anti GM1 antibodies". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 12 (7): 808–10. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2004.09.019. PMID 16054817. S2CID 35425147.

Further reading

edit- http://health.nytimes.com/health/guides/disease/acute-cerebellar-ataxia/overview.html[full citation needed]

- https://web.archive.org/web/20111021044049/http://www.bettermedicine.com/article/cerebellar-ataxia-syndrome/symptoms%7B%7Bfull%7Cdate%3DAugust 2015

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Acute cerebellar ataxia