Hindu and Buddhist heritage of Afghanistan

Communities of various religious and ethnic backgrounds have lived in the land of what is now Afghanistan. Before the Islamic conquest, the south of the Hindu Kush was ruled by the Zunbil and Kabul Shahi rulers. When the Chinese travellers (Faxian, Song Yun, Xuanzang, Wang-hiuon-tso, Huan-Tchao, and Wou-Kong) visited Afghanistan between 399 and 751 AD, they mentioned that Hinduism and Buddhism were practiced in different areas between the Amu Darya (Oxus River) in the north and the Indus River in the south.[1] The land was ruled by the Kushans followed by the Hephthalites during these visits. It is reported that the Hephthalites were fervent followers of the Hindu god Surya.[2]

The invading Muslim Arabs introduced Islam to a Zunbil king of Zamindawar (Helmand Province) in 653-4 AD. They took the same message to Kabul before returning to their already Islamized city of Zaranj in the west. It is unknown how many accepted the new religion, but the Shahi rulers remained non-Muslim until they lost Kabul in 870 AD to the Saffarid Muslims of Zaranj. Later, the Samanids from Bukhara in the north extended their Islamic influence into the area. It is reported that Muslims and non-Muslims still lived side by side in Kabul before the arrival of Ghaznavids from Ghazni.

"Kábul has a castle celebrated for its strength, accessible only by one road. In it there are Musulmáns, and it has a town, in which are infidels from Hind."[3]

— Istakhri, 921 AD

The first mention of a Hindu in Afghanistan appears in the 982 AD Ḥudūd al-ʿĀlam, where it speaks of a king in "Ninhar" (Nangarhar), who shows a public display of conversion to Islam, even though he had over 30 wives, which are described as "Muslim, Afghan, and Hindu" wives.[4] These names were often used as geographical terms by the Arabs. For example, Hindu (or Hindustani) has been historically used as a geographical term to describe someone who was native to the region known as India, and Afghan as someone who was native to a region called Bactria.

Archeology

edit| Location | Artifacts found | Other information |

|---|---|---|

| Hindu temple at Khair Khaneh in Kabul. | Marble statues of Surya, the Hindu god of sun.[5] | |

| Gardez | Statues of Durga Mahishasuramardini.[5] | They show Hindu Goddess Durga, the consort of Shiva, slaying buffalo demon Mahishasura. |

| Hindu Temple at Chaghan Saray in the Kunar Valley in eastern Afghanistan.[5] | Temple complex | |

| Tapa Skandar 31 km north of Kabul.[5] | Remains of settlement dating to the second half of the first millennium AD. Marble statue of Shiva and his wife Parvati.[5] | |

| Tapa Sadr near Ghazni.[5] | Statue of the Parinivana Buddha (Buddha lying down at the end of his cycle of rebirths).[5] | 8th century AD |

| Gardez | Śāradā script engraved on a marble statue of an elephant deity Ganesh brought by the Hindu Shahis who occupied the Kabul Valley.[5] | 8th century AD |

| Nava Vihara Balkh | ||

| Airtam Near Termez | A stone slab with a Bactrian inscription and a carved image of Shiva.[6] | |

| Tepe Sardar, Ghazni | Large Buddhist monastery complex[7] | The main Stupa is surrounded by many miniature stupas and shrines, ornamented with clay bas reliefs. There were several colossal statues of the Buddha, included one seated and of the Buddha in Nirvana. In one shrine which is in the Hindu style a clay sculpture of Durga slaying a buffalo-demon was found.[7] |

| Homay Qala in Ghazni | Buddhist Cave Complex at Homay Qalay.[8] | |

| Tepe Sardar Ghazni | Durga clay - 10th Century.[9] | 10th Century AD.[9] Durga was popularised during the Shahi period as several images of this deity are found in Afghanistan.[10] |

| Various | Coins of the Shahi rulers of Panjab and Afghanistan have been found.[11] | 650-1000 AD[12] These coins were issued from at least eight mint towns, which suggests a wider range for their circulation[11] |

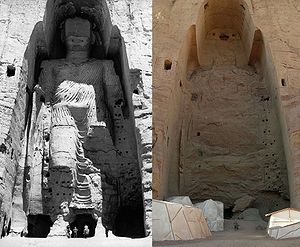

| Buddhas of Bamiyan Bamyan Province Hazarajat region |

Believed to be built in 507 AD, the larger in 554 AD. Destroyed in 2001 by the Taliban. | |

| Khair Khana Kabul[11] | Hindu Temple,[11] two marble statues of Shiva[11] | |

| Basawal | Basawal is the site of a Buddhist cave temple complex in eastern Afghanistan. The caves, 150 in all, are partly hewn out in two rows and arranged in seven groups, which presumably correspond to the seven monastic institutions of Buddhist times.[13] | |

| Buddhist cave complex at Homay Qala[14] |

Table of pre-Islamic dynasties of Afghanistan

edit| Dynasty | Period | Domain | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hindu Shahis | Closing years of the 10th and the early 11th century. Jayapala was defeated by Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni.[15] in 1013 Kabul's last Shahi ruler [16] |

|

Gandhara (eastern Afghanistan and northwestern Pakistan) was overrun by Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni.[15] (Kabul valley) |

| Zunbils | The Zunbils were finally deposed by Ya'qub Saffari in 870 AD, founder of the Saffarid dynasty in Zaranj.[18][19] | Zabulistan (southern Afghanistan).[19] |

Islamic conquest of Afghanistan

editThe region around Herat Province became Islamized in 642 AD, during the end of Muslim conquest of Persia. In 653-4 AD, General Abdur Rahman bin Samara arrived from Zaranj to the Zunbil capital Zamindawar with an army of around 6,000 Arab Muslims. The General "broke off a hand of the idol and plucked out the rubies which were its eyes to persuade the Marzbān of Sīstān of the god's worthlessness."[20] He explained to the worshippers of the solar deity, "My intention was to show you that this idol can do neither any harm nor good."[2] The people of southern Afghanistan began accepting Islam from this date onward. The Arabs then proceeded to Ghazni and Kabul to convert or conquer the Buddhist Shahi rulers. However, most historians claim that the rulers of Ghazni and Kabul remained non-Muslim. There is no information on the number of converts, although the Arabs unsuccessfully continued their missions of invading the land to spread Islam for the next 200 or so years. It was in 870 AD when Ya'qub ibn al-Layth al-Saffar finally conquered Afghanistan by establishing Muslim governors throughout the provinces.

"Arab armies carrying the banner of Islam came out of the west to defeat the Sasanians in 642 AD and then they marched with confidence to the east. On the western periphery of the Afghan area the princes of Herat and Seistan gave way to rule by Arab governors but in the east, in the mountains, cities submitted only to rise in revolt and the hastily converted returned to their old beliefs once the armies passed. The harshness and avariciousness of Arab rule produced such unrest, however, that once the waning power of the Caliphate became apparent, native rulers once again established themselves independent. Among these the Saffarids of Seistan shone briefly in the Afghan area. The fanatic founder of this dynasty, the coppersmith's apprentice Yaqub ibn Layth Saffari, came forth from his capital at Zaranj in 870 AD and marched through Bost, Kandahar, Ghazni, Kabul, Bamyan, Balkh and Herat, conquering in the name of Islam.".[21]

— Nancy Dupree, 1971

By the 11th century, when the Ghaznavids were in power, the entire population of Afghanistan was practicing Islam, except the Kafiristan region (Nuristan Province) which became Muslim in the late 1800s.

See also

edit- Gandharan Buddhism

- Gandhāran Buddhist texts

- Ancient history of Afghanistan

- Pre-Islamic scripts in Afghanistan

- Buddhism in Afghanistan

- Hinduism in Afghanistan

- Buddhas of Bamiyan

- Kandahar Greek Edicts of Ashoka

- Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription

- Gandhara Kingdom

- Nava Vihara

- Zabulistan

- Decline of Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent

References

edit- ^ "Chinese Travelers in Afghanistan". Abdul Hai Habibi. alamahabibi.com. 1969. Archived from the original on December 24, 2018. Retrieved August 9, 2012.

- ^ a b "Amir Kror and His pAncestry". Abdul Hai Habibi. alamahabibi.com. Archived from the original on October 19, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ "A.—The Hindu Kings of Kábul (p.3)". Sir H. M. Elliot. London: Packard Humanities Institute. 1867–1877. Archived from the original on July 26, 2013. Retrieved September 18, 2010.

- ^ Vogelsang, Willem (2002). The Afghans. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 18. ISBN 0-631-19841-5. Archived from the original on 2023-02-04. Retrieved 2012-08-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h The Afghans By Willem Vogelsang Page 184

- ^ History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume 3 By Boris Abramovich Litvinovskiĭ Page 427

- ^ a b History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume 3 By Boris Abramovich Litvinovskiĭ Page 399

- ^ "South Asian archaeology 1975: papers from the third International Conference Edited by Johanna Engelberta Lohuizen-De Leeuw Page 121 to 126". Archived from the original on 2023-06-20. Retrieved 2022-08-13.

- ^ a b History of Buddhism in Afghanistan By Sī. Esa Upāsaka, Kendrīya-Tibbatī-Ucca-Śikṣā-Saṃsthānam page XX

- ^ History of Buddhism in Afghanistan By Sī. Esa Upāsaka, Kendrīya-Tibbatī-Ucca-Śikṣā-Saṃsthānam page 187

- ^ a b c d e Early medieval Indian society: a study in feudalisation By R.S. Sharma page 130

- ^ Early medieval Indian society: a study in feudalisation By R.S. Sharma Page 130

- ^ Encyclopedia Iranica

- ^ Leeuw, Johanna Engelberta Lohuizen-De (1979). South Asian Archaeology 1975: Papers from the Third International Conference of the Association of South Asian Archaeologists in Western Europe Held in Paris. BRILL. p. 119. ISBN 978-90-04-05996-2. Archived from the original on 2023-06-20. Retrieved 2022-08-13.

- ^ a b The races of Afghanistan Being a brief account of the principal nations inhabiting that country, by Henry Walter Bellow Asian Educational services, Page 73

- ^ Pakistan and the emergence of Islamic militancy in Afghanistan By Rizwan Hussain page 17

- ^ Encyclopaedia of Historiography By M.M. Rahman

- ^ Medieval India Part 1 by Satish Chandra Page 17

- ^ a b Excavations at Kandahar 1974 & 1975 (Society for South Asian Studies Monograph) by Anthony McNicoll

- ^ André Wink, "Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World", Brill 1990. p 120

- ^ Dupree, Nancy (1971) "Sites in Perspective (Chapter 3)" An Historical Guide To Afghanistan Afghan Tourist Organization, Kabul, OCLC 241390 Archived 2009-09-05 at the Wayback Machine

External links

edit- Professor Abdul Hai Habibi See article The Cultural, Social And Intellectual State Of The People Of Afghanistan In The Era Just Before The Advent Of Islam by eminent Afghan historian Abdul Hai Habibi

- Shahi Coins in the Standard Catalog of World Coins 1901-2000 By Colin R. Bruce, Thomas Michael Page 35

- Afghan caves contain world's first oil paintings

- Buddhist Sites in Afghanistan and Central Asia