This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2024) |

Primary direction is a term in astrology for referencing one of the oldest methods of predicting events. It indicates the year of life in which an event shown by the birth chart will occur. This method has been around for over 1800 years and is mentioned in the Tetrabiblos of Claudius Ptolemy in the section on calculating the length of life. It gained widespread popularity in medieval Europe and was thoroughly described by Jean-Baptiste Morin (a.k.a. Morinus) in the 22nd book of his Astrologia Gallica.[1]

The method involves two sensitive points of the horoscope - the promittor and the significator. The significator indicates the area of life where the event will occur, while the promittor indicates what will cause this event.

The method

editThe essence of the method is as follows:

- The significator remains fixed on the celestial sphere relative to the local horizon.

- The promittor moves along with the daily rotation of the celestial sphere until it approaches the significator.

The number of degrees the promittor passes to join the significator indicates the year of life when the event will occur.

Since the movement of the promittor towards the significator occurs due to the rotation of the celestial sphere, known as primary motion, this method is called primary directions.

Interpretation

editLet's consider an example to illustrate the essence of the method better. Suppose the promittor indicates disputes and conflicts with parents in the horoscope. And suppose, at 41 degrees, it meets with the significator of wealth due to primary motion. It means that around 41 years, the person will acquire wealth by winning a lawsuit against his parents.

Several directions occur in a person's life each year. However, not all of them bring results. Morinus claimed in section IV, chapter 1 of 22-nd book of "Astrologia Gallica"[1] that direction brings an event if the significator and the promittor are bright creators or destroyers of things in certain areas of life. This indicator is based on the position of planets in the natal chart.

The Key Features

editPromittor and Significator

editAccording to Morinus, the promittor can be:

- Planets of the horoscope

- Aspects and antiscia of planets

- Fixed stars

The significator can be:

- Planets of the horoscope

- House cusps

- Arabian Part of Fortune

Mundane conjunction

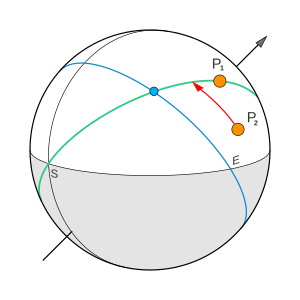

editThe key difference between primary directions and zodiacal aspects is that the promittor and significator are conjunct not on the zodiacal circle but on the celestial sphere. Therefore, knowledge of spherical geometry is required to calculate such a conjunction.

The mundane (basically spatial) conjunction of planets on the sphere is constructed as follows:

- A dividing line is passed through the significator. This line is drawn according to the algorithm dividing the celestial sphere into house sectors.

- The significator and dividing line remain stationary relative to the local horizon.

- When the moving promittor crosses this line, it spatially conjuncts with the significator at that moment.

Mundane aspect

editAstrologers have long debated in which plane to construct a planet's aspect to choose it as a promittor. Some used the plane of the zodiacal circle or a plane parallel to it. Others used the equator plane. These differences in opinion led to various types of primary directions - mundane, zodiacal, field plane, and so on.[2]

In the 15th century, Professor of Mathematics Giovanni Bianchini proposed his model for calculating the aspect plane. However, in the 17th century, Morinus created his system for calculating the circle of aspects,[3] allowing him to predict events with precision not to the year but several months. He brought many illustrative examples of how it works in the 22nd book of "Astrologia Gallica."

Converse directions

editIn reverse (or converse) directions, the significator, with the separating line that passes through it, rotates along with the celestial sphere. All other points of the horoscope remain stationary relative to the horizon. Everything that crosses the separating line during such a movement became a promittor.

- Example of direct direction. Suppose a planet is directed towards a spatial conjunction with a fixed house cusp. Then the fixed cusp is the significator, and the planet is the promittor.

- Example of converse direction. Suppose the cusp of a house is directed towards a spatial conjunction with a fixed planet or the star. Then the moving cusp is the significator (the cusp cannot be the significator, as said above), and the fixed planet/star is the promittor.

Both types of directions produce events equally.

Accuracy

editPrimary directions point not to exact but approximate event dates. The usual accuracy is up to several months. For more precise dates (with an accuracy of 1–2 days), astrologers use refining prediction methods such as planet revolutions, progressions, and transits.

Modern usage

editThis method of predicting future events[4] is practically unused nowadays due to the mathematical difficulty it presents. In addition, those who consider astrology to be a pseudoscience do not calculate predictions according to celestial movements (except when calculating astronomical events); instead they rely on statistical knowledge of past events and correlate them with probabilities of future events to make their predictions.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Morin, Jean-Baptiste (1661). Astrologia gallica principiis & rationibus propriis stabilita atque in XXVI libros distributa / opera & studio Joannis Baptistae Morini. ex Typograhia Adriani Vlacq. doi:10.3931/e-rara-1874.

- ^ Makransky, Bob (1988). Primary Directions. Dear Brutus Press. p. 25. ISBN 096773150X.

- ^ Rusborn, Mark (2023-03-26). "How to construct the circle of aspects in directions". morinus-astrology.com. Retrieved 2023-04-05.

- ^ Gansten, Martin (2009). Primary directions : astrology's old master technique. Bournemouth, Eng.: Wessex Astrologer. ISBN 978-1-902405-39-1. OCLC 320197873.