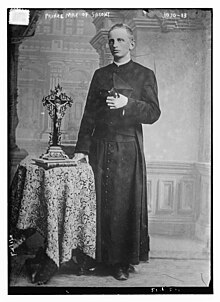

Prince Maximilian William Augustus Albert Charles Gregory Odo of Saxony, Duke of Saxony (German: Maximilian Wilhelm August Albert Karl Gregor Odo; 17 November 1870 – 12 January 1951) was a member of the Albertine branch of the House of Wettin and a Catholic priest.

| Prince Maximilian | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Born | 17 November 1870 Dresden, Kingdom of Saxony, North German Confederation | ||||

| Died | 12 January 1951 (aged 80) Fribourg, Canton of Fribourg, Switzerland | ||||

| |||||

| House | Wettin | ||||

| Father | George of Saxony | ||||

| Mother | Infanta Maria Anna of Portugal | ||||

| Religion | Catholicism | ||||

Early life

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2017) |

Maximilian Wilhelm August Albert Karl Gregor Odo of Saxony was born in Dresden, capital of the Kingdom of Saxony, the seventh of the eight children of Prince George of Saxony and his wife Infanta Maria Anna of Portugal. He was born with the titles Prince and Duke of Saxony, with the style Royal Highness. Amongst his siblings was the last Saxon king Frederick Augustus III and Princess Maria Josepha mother of the last Austrian Emperor Charles I.

Priesthood

editOn 26 July 1896, despite initial opposition from his family, Prince Maximilian decided to study for the priesthood and was subsequently ordained a Catholic priest.[1][2] He renounced his claim to the throne of Saxony on entering the priesthood and also expressed a determination to refuse the apanage that he was entitled to from the Kingdom of Saxony.[3][4]

Professor

editIn January 1899 Prince Maximilian graduated Doctor of Theology from the University of Würzburg.[4] After working as a pastor at a church in Nuremberg, on 21 August 1900 Prince Maximilian accepted the post of Professor of Canon Law at the University of Fribourg.[5][6]

In late 1910 Prince Maximilian caused controversy by publishing an article in an ecclesiastical periodical on the union of the Eastern and Roman churches. Prince Maximilian argued that the six dogmas should be waived in order to facilitate the return of the Eastern to the Catholic Church.[7] Consequently, upon the article he went to see Pope Pius X to explain, and as a result of the meeting agreed to retract the article and signed a declaration acknowledging errors in it. It was announced that he had renewed his full and unconditional adhesion to the doctrines of the Catholic Church.[8][9]

War

editDuring the First World War Prince Maximilian served as an Army chaplain and in this capacity he attended to wounded soldiers, gave unction to the dying and said mass while under shell fire. He was liked by the French prisoners of war as he also dedicated himself to their welfare. He also used the international bureau in Geneva to send word to the families of the French prisoners.[10]

Following the German Empire's defeat in the war his brother King Frederick Augustus III was forced to abdicate as the monarchy was abolished.

Death

editPrince Maximilian died in Fribourg, Switzerland, as the last surviving grandchild of Queen Maria II and King Fernando II of Portugal, and last great-grandchild of Pedro IV of Portugal & I of Brazil.

Honours

edit- Kingdom of Saxony: Knight of the Order of the Rue Crown[11]

- Kingdom of Prussia: Knight of the Order of the Black Eagle[11]

- Baden: Knight of the House Order of Fidelity, 1908[12]

- Kingdom of Bavaria: Knight of the Order of St. Hubert, 1898[13]

- Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach: Grand Cross of the Order of the White Falcon, 1890[14]

- Austria-Hungary: Grand Cross of the Order of St. Stephen, 1891[15]

Ancestry

edit| Ancestors of Prince Maximilian of Saxony (1870–1951) |

|---|

References

edit- ^ "A Prince Ordained A Priest". New York Times. 1896-07-26. p. 1.

- ^ "Knowledge Means Peace". New York Times. 1896-07-19. p. 4.

- ^ "Prince as Priest in London". The West Australian. 1896-10-23. p. 9.

- ^ a b "An Unruly German Press". New York Times. 1899-01-29. p. 17.

- ^ "Object to Prince-Evangelist". New York Times. 1900-11-13. p. 5.

- ^ "Saxon Prince a Professor". New York Times. 1900-08-22. p. 6.

- ^ "Pope To Eastern Churches". New York Times. 1911-01-03. p. 8.

- ^ "Prince Submits to the Pope". New York Times. 1910-12-28. p. 5.

- ^ "Prince Maximilian Recants". New York Times. 1910-12-31. p. 5.

- ^ "Peace of the World". New York Times. 1915-02-28. p. SM3.

- ^ a b Justus Perthes, Almanach de Gotha (1923) p. 109

- ^ Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Großherzogtum Baden (1910), "Großherzogliche Orden" p. 41

- ^ Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Königreich Bayern (1908), "Königliche Orden" p. 9

- ^ Staatshandbuch für das Großherzogtum Sachsen / Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach (1900), "Großherzogliche Hausorden" p. 16

- ^ "A Szent István Rend tagjai" Archived 22 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine