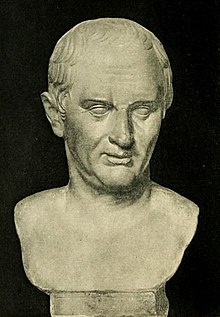

Pro Tito Annio Milone ad iudicem oratio (or Pro Milone) is a speech made by Marcus Tullius Cicero in 52 BC on behalf of his friend Titus Annius Milo. Milo was accused of murdering his political enemy Publius Clodius Pulcher on the Via Appia. Cicero wrote the speech after the hearing and so the authenticity of the speech is debated among scholars.

Background to trial

editMilo was a praetor at the time who was attempting to gain the much-wanted post of consul. Clodius was a former tribune standing for the office of praetor. The charge was brought against Milo for the death of Clodius following a violent altercation on the Via Appia, outside Clodius' estate in Bovillae. After the initial brawl, it seems that Clodius was wounded during the fight that was started by both men's slaves.

The sequence of events described by the prosecution and the commentary of Asconius Pedianus (c. 100 AD), an ancient commentator who analyzed several of Cicero's speeches and had access to various documents that no longer exist, was this: the absence of a summary of the chain of events in Cicero's speech may be attributed to their incriminating evidence against Milo. Presumably, Cicero correctly realised that to be the primary weakness. It can be assumed, from the fact that the jury indeed convicted Milo, that it felt that although Milo may not have been aware of Clodius's initial injury, his ordering of Clodius' butchering warranted punishment.[citation needed]

When initially questioned about the circumstances of Clodius' death, Milo responded with the excuse of self-defense and that it was Clodius who laid a trap for Milo to kill him. Cicero had to fashion his speech to be congruent with Milo's initial excuse, a restraint that probably affected the overall presentation of his case. To convince the jury of Milo's innocence, Cicero used the fact that following Clodius death, a mob of Clodius' own supporters, led by the scribe Sextus Cloelius, carried his corpse into the Senate house (curia) and cremated it using the benches, platforms, tables and scribes' notebooks, as a pyre. In doing so, it also burnt down much of the curia;[1] Clodius' supporters also launched an attack on the house of the then interrex, Marcus Lepidus. Pompey thus ordered a special inquest to investigate that as well as the murder of Clodius. Cicero refers to this incident throughout the Pro Milone by implying that there was greater general indignation and uproar at the burning of the curia than there was at the murder of Clodius.[2]

The violent nature of the crime as well as its revolutionary repercussions (the case had special resonance with the Roman people as a symbol of the clash between the populares and the optimates) made Pompey set up a handpicked panel of judges. Thus, he avoided the corruption, rife in the political scene of the late Roman Republic. In addition, armed guards were stationed around the law courts to placate the violent mobs of both sides' supporters.

Beginning of trial

editThe first four days of the trial were dedicated to opposition argument and the testimony of witnesses. On the first day, Gaius Causinius Schola appeared as a witness against Milo and described the deed in such a way as to portray Milo as a coldblooded murderer. That worked up Clodius' supporters, who terrified the advocate on Milo's side, Marcus Marcellus. As he began his questioning of the witnesses, the crowd drowned out his voice and surrounded him.[3] The action taken by Pompey prevented much furore from the vehemently anti-Milo crowds for the rest of the case. On the second day of the trial, the armed cohorts were introduced by Pompey. On the fifth and final day, Cicero delivered Pro Milone in the hope of reversing the damning evidence, accrued over the previous days.

Content of speech

editThroughout the duration of his speech, Cicero does not even attempt to convince the judges that Milo did not kill Clodius. However there is a point in the speech where Cicero claims that Milo neither knew about nor saw Clodius's murder. Cicero claims that the killing of Clodius was lawful and in self-defense. Cicero even goes as far as to suggest that the death of Clodius was in the best interests of the republic, as the tribune was a popularis leader of the restless plebeian mobs who had plagued the political scene of the late Roman Republic. Possibly Cicero's strongest argument was that of the circumstances of the assault: its convenient proximity to Clodius' villa and the fact that Milo was leaving Rome on official business: nominating a priest for election in Lanuvium. Clodius, on the other hand, had been distinctly absent from his usual rantings in the popular assemblies (contiones). Milo was encumbered in a coach, with his wife, a heavy riding cloak and a retinue of harmless slaves (but his retinue also included slaves and gladiators as well as revellers for the festival at Lanuvium, and Cicero only implies their presence). Clodius, however, was on horseback not with a carriage, his wife or his usual retinue but with a band of armed brigands and slaves. If Cicero could convince the judges that Clodius had laid a trap for Milo, he could postulate that Clodius had been killed in self-defense. Cicero never even mentions the possibility that the two met by chance, the conclusion of both Asconius[4] and Appian.[5]

Clodius is made out repeatedly in the Pro Milone to be a malevolent, invidious, effeminate character who craves power and organises the ambush on Milo. Cicero gives Clodius a motive for setting a trap: the realisation that Milo would easily secure the consulship and so stand in the way of Clodius' scheme to attain greater power and influence as a praetor. Fortunately, there was plentiful material for Cicero to build that profile, such as the Bona Dea incident in 62 BC; involving Clodius stealing into the abode of the Pontifex Maximus of the time, Julius Caesar, during the ritual festival of the Bona Dea to which only women were allowed. It is said that he dressed up as a woman to gain access and pursue an illicit affair with Pompeia, the wife of Caesar.[6] Clodius was taken to the law courts for this act of great impiety but escaped the punishment of death by bribing the judges, most of whom had been poor, according to Cicero, who was the prosecutor during the case.

Earlier in his career, Lucullus had accused Clodius of committing incest with his sister Claudia and then Lucullus's wife; this allegation is mentioned several times to blacken Clodius' reputation.

Milo, on the other hand, is perpetually depicted as a 'saviour of Rome' by his virtuous actions and political career up until then. Cicero even goes as far as to paint an amicable relationship with Pompey. Asconius, as he does with many other parts of the Pro Milone, disputes that by claiming that Pompey was in fact "afraid" of Milo "or else pretended to be afraid",[7] and he slept outside on the highest part of his property in the suburbs and had a constant body of troops to keep guard. His fear was attributed to a series of public assemblies in which Titus Munatius Plancus, a fervent supporter of Clodius, stirred up the crowd against Milo and Cicero and cast suspicion on Milo by shouting that he was preparing a force to destroy him.[8]

However, in the view of Plutarch, a 1st-century AD writer and biographer of notable Roman men, Clodius had also stirred up enmity between Pompey and himself along with the fickle crowds of the forum he controlled, with his malevolent goading.[9]

The early part of the refutation of the opposition's arguments (refutatio), contains the first known exposition of the phrase silent enim leges inter arma[10] ("in times of war, the laws fall silent"). It has since been rephrased as inter arma enim silent leges, and was most recently used by the American media in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001. The phrase is integral to Cicero's argument. In the context of the Pro Milone the meaning behind the phrase remains the same as its use in contemporary society. Cicero was asserting that the killing of Clodius was admissible if it was an act of self-defence. The argument is that in extreme cases, when one's own life is immediately threatened, disregard of the law is justifiable. Indeed, Cicero goes as far as to say that such behaviour is instinctive (nata lex:[11] "an inborn law") to all living creatures (non instituti, sed imbuti sumus: "we are not taught [self-defence] through instruction, but through natural intuition"). The argument of the murder of Clodius being in the public interest is only presented in the written version of the Pro Milone, as, according to Asconius, Cicero did not mention it in the actual version delivered.[12]

The speech also contains the first known use of the legal axiom res ipsa loquitur but in the form res loquitur ipsa, (literally, "the thing itself speaks", but it is usually translated as "the facts speak for themselves").[13][14] The phrase was quoted in an 1863 judgment in the English case Byrne v Boadle and became the tag for a new common law doctrine.[15]

Outcome

editIn the account of later writer and Ciceronian commentator Asconius, the actual defense failed to secure an acquittal for Milo for three reasons:

- Cicero's intimidation by the Clodius' mob on the final day[16]

- The political pressure exerted by Pompey for the judges to convict Milo

- The sheer number of testimonies against Milo over the course of the case.

Milo was condemned for the murder by a margin of 38 votes to 13.[17] Milo went into exile to the Gallic town of Massilia (Marseille). During his absence, Milo was prosecuted for bribery, unlawful association and violence, of all of which he was successfully convicted. As an example of the volatile, contradictory and confusing political atmosphere of the time, the superintendent of Milo's slaves, one Marcus Saufeius, was also prosecuted for the murder of Clodius shortly after the conviction of Milo. The team of Cicero and Marcus Caelius Rufus defended him and managed to acquit Saufeius by a margin of one vote. Furthermore, Clodius' supporters did not all escape unscathed. Clodius' associate, Sextus Cloelius, who supervised the cremation of Clodius' corpse, was prosecuted for the burning down of the curia and was convicted by an overwhelming majority of 46 votes.[18]

Aftermath

editFollowing the trial, violence raged unchecked in the city between supporters of Clodius and Milo. Pompey had been made sole consul in Rome during the violent troubled times after the murder but before the legal proceedings against Milo had begun.[19] He quelled the riots following this string of controversial cases with brutal military efficiency, temporarily regaining stability in Rome.

The Pro Milone text that survives now is a rewritten version, published by Cicero after the trial. Despite its failure to secure an acquittal, the surviving rewrite is considered to be one of Cicero's best works and is thought by many to be the magnum opus of his rhetorical repertoire. Asconius describes the Pro Milone as "so perfectly written that it can rightly be considered his best".[20]

The speech is full of deceptively straightforward strategies. Throughout his speech, Cicero explicitly seems to follow his own rhetorical guidelines published in his earlier work De Inventione, but on occasion, he subtly breaks away from the stylistic norms to emphasise certain elements of his case and use the circumstances to his advantage. As example, he places his refutation of the opposition's arguments (refutatio) far earlier in the speech than is usual, and he pounces on the opportunity for a fast disproval of the plethora of evidence collected over the first four days of the trial. His arguments are interwoven with one another and coalesce during the conclusion (peroratio). There is heavy use of pathos throughout the speech, starting with his assertion of fear for the guards posted around the courts by Pompey in the special inquisition (the very first sentence of the speech contains the word vereor – "I fear").

However, Cicero ends his speech fearless, becomes more emotive with each argument and finishes by the beseeching of his audience with tears to acquit Milo. Irony is omnipresent in the speech, along with continual appearances of humour and constant appeals to traditional Roman virtues and prejudices, all of the tactics designed solely to involve and persuade his jury.[citation needed]

In many ways, the circumstances surrounding the case were apposite for Cicero, forcing him back to his own oratorical foundations. The charge of vis (violence) against Milo not only suited a logical and analytical legal framework, with evidence indicating a specific time, date, place and cast for the murder itself, but also generally concerned actions that affected the community. That allowed Cicero ample maneuvering room to include details of the fire in the curia as well as the attack on Marcus Lepidus' house and the Bona Dea incident.[citation needed]

Milo, having read the later published speech whilst in exile, joked that if Cicero had spoken that well in court, the former would "not now be enjoying the delicious red mullet of Massilia".[21]

References

edit- ^ Asconius, Pro Milone, 33C

- ^ Asconius, Pro Milone, 33C

- ^ Asconius, Pro Milone, 40C

- ^ Asconius, Pro Milone, 41C

- ^ Appian, The Civil Wars, II.21)

- ^ Plutarch, Roman Lives: Life of Caesar, 9-10

- ^ Asconius, Pro Milone, 36C

- ^ Asconius, Pro Milone, 37C–38C

- ^ Plutarch, Roman Lives: Life of Pompey, 48-49

- ^ Cicero, Pro Milone, 11

- ^ Cicero, Pro Milone, 10

- ^ Cicero, Pro Milone, 10

- ^ Cic. Pro Milone 53

- ^ “Medical Jurisprudence”, p. 88, Jon R. Waltz, Fred Edward Inbau, Macmillan, 1971, ISBN 0-02-424430-9

- ^ "The Law of falling Objects: Byrne v. Boadle and the Birth of Res Ipsa Loquitur", page 1079, by G. Gregg Webb, Stanford Law Review, vol. 59, iss.4.

- ^ Asconius, Pro Milone, 41C

- ^ Asconius, Pro Milone, 53C

- ^ Asconius, Pro Milone, 56C

- ^ Asconius, Pro Milone, 36C

- ^ Asconius, Pro Milone, 42C

- ^ Dio, 40.54.3

Bibliography

edit- MacKendrick, P. The Speeches of Cicero, London, 1995

- Rawson, B. The Politics of Friendship: Pompey & Cicero, Letchworth, 1978

- Berry, D.H. Pompey's Legal Knowledge – or Lack of it, Historia 42, 1993 (article: pp. 502–504)

- Casamento, A., Spettacolo della giustizia, spettacolo della parola: il caso della pro Milone, in: Petrone, G. & Casamento, A. (Eds.), Lo spettacolo della giustizia. Le orazioni di Cicerone, Palermo 2006, pp. 181–198.

- Casamento, A., La pro Milone dopo la pro Milone, in Calboli Montefusco, L.(Ed.), Papers on rhetoric X, Roma 2010 (article: pp. 39–58).

- Casamento A., Strategie retoriche, emozioni e sentimenti nelle orazioni ciceroniane. Le citazioni storiche nella pro Milone, ὅρμος N.S. 3, 2011 (article: pp. 140–151).

- Casamento A., Apparizioni, fantasmi e altre ‘ombre’ in morte e resurrezione dello Stato. Fictio, allegoria e strategie oratorie nella pro Milone di Cicerone, in: Moretti, G. & Bonandini, A. (Eds.), Persona ficta. La personificazione allegorica nella cultura antica fra letteratura, retorica e iconografia, Trento 2012 (article: pp. 139–169).

- Clark, M.E. & Ruebel, J.S. Philosophy & Rhetoric in Cicero's Pro Milone, RhM 128, 1985 (article: pp. 57–72)

- Fezzi, L. Il tribuno Clodio, Roma-Bari 2008.

- Fotheringham, L. Persuasive Language in Cicero's Pro Milone: A Close Reading and Commentary (BICS Supplement 121), London: Institute of Classical Studies, 2013 ISBN 978-1-905670-48-2

- Ruebel, James S., "The Trial of Milo in 52 B.C.: A Chronological Study", Transactions of the American Philological Association Vol. 109 (1979), pp. 231–249, American Philological Association.

- Stone, A.M. Pro Milone: Cicero's second thoughts, Antichthon 14, 1980 (article: pp. 88–111)

- Tatum, W.J. The Patrician Tribune. Publius Clodius Pulcher, Chapel Hill 1999.

- West, R. and Lynn Fotheringham. Cicero Pro Milone: A Selection, London and New York: Bloomsbury 2016 ISBN 1474266185

External links

edit- Works related to For Milo at Wikisource

- Latin Wikisource has original text related to this article: Pro Milone

- Pro Milone in Latin, at The Latin Library

- Pro Milone in English, translated by C.D. Yonge, at perseus.tufts.edu

- Pro Milone in English, with extracts from the commentary of Asconius, translated by N.H.Watts, at attalus.org