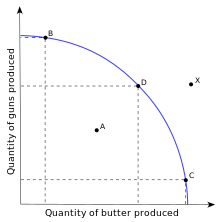

In microeconomic theory, productive efficiency (or production efficiency) is a situation in which the economy or an economic system (e.g., bank, hospital, industry, country) operating within the constraints of current industrial technology cannot increase production of one good without sacrificing production of another good.[1] In simple terms, the concept is illustrated on a production possibility frontier (PPF), where all points on the curve are points of productive efficiency.[2] An equilibrium may be productively efficient without being allocatively efficient — i.e. it may result in a distribution of goods where social welfare is not maximized (bearing in mind that social welfare is a nebulous objective function subject to political controversy).

Productive efficiency is an aspect of economic efficiency that focuses on how to maximize output of a chosen product portfolio, without concern for whether your product portfolio is making goods in the right proportion; in misguided application, it will aid in manufacturing the wrong basket of outputs faster and cheaper than ever before.

Productive efficiency of an industry requires that all firms operate using best-practice technological and managerial processes and that there is no further reallocation that bring more output with the same inputs and the same production technology. By improving these processes, an economy or business can extend its production possibility frontier outward, so that efficient production yields more output than previously.

Productive inefficiency, with the economy operating below its production possibilities frontier, can occur because the productive inputs physical capital and labor are underutilized—that is, some capital or labor is left sitting idle—or because these inputs are allocated in inappropriate combinations to the different industries that use them.

In long-run equilibrium for perfectly competitive markets, productive efficiency occurs at the base of the average total cost curve — i.e. where marginal cost equals average total cost — for each good.

Due to the nature and culture of monopolistic companies, they may not be productively efficient because of X-inefficiency, whereby companies operating in a monopoly have less of an incentive to maximize output due to lack of competition. However, due to economies of scale it can be possible for the profit-maximizing level of output of monopolistic companies to occur with a lower price to the consumer than perfectly competitive companies.

Theoretical measures

editMany theoretical measures of production efficiency have been proposed in the literature as well as many approaches to estimate them.

The most popular measures of efficiency include Farrell measure[3] (also known as Debreu–Farrell measure, since Debreu (1951) has similar ideas[4]). This measure is also the reciprocal of the Shephard's distance function.[5] These can be defined with either the input orientation (fix outputs and measure maximal possible reduction in inputs) or the output orientation (fix inputs and measure maximal possible expansion in outputs).

A generalisation of these is the so-called directional distance function, where one can select any direction (or orientation) for measuring the production efficiency.

The most popular for estimating production efficiency are data envelopment analysis[6] and stochastic frontier analysis.[7]

See the recent book by Sickles and Zelenyuk (2019) for comprehensive coverage of the theory[which?] and related estimation and many references therein.[8]

References

edit- ^ Sickles, R., & Zelenyuk, V. (2019). Measurement of Productivity and Efficiency: Theory and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781139565981

- ^ Standish, Barry (1997). Economics: Principles and Practice. South Africa: Pearson Education. pp. 13–15. ISBN 978-1-86891-069-4.

- ^ Farrell, M. J. (1957). The measurement of productive efficiency. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (General), 120(3):253–290.

- ^ Debreu, G. (1951). The coefficient of resource utilization. Econometrica, 19(3):273–292.

- ^ Shephard, R. W. (1953). Cost and Production Functions. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Charnes, A., Cooper, W., and Rhodes, E. (1978). Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. European Journal of Operational Research, 2(6):429–444.

- ^ Aigner, D. J., Lovell, C. A. K. & Schmidt, P. (1977), 'Formulation and estimation of stochastic frontier production functions', Journal of Econometrics 6(1), 21–37.

- ^ Sickles, R., & Zelenyuk, V. (2019). Measurement of Productivity and Efficiency: Theory and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781139565981