Pygmalion is a play by Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw, named after the Greek mythological figure. It premiered at the Hofburg Theatre in Vienna on 16 October 1913 and was first presented on stage in German. Its English-language premiere took place at His Majesty's Theatre in London's West End in April 1914 and starred Herbert Beerbohm Tree as phonetics professor Henry Higgins and Mrs Patrick Campbell as Cockney flower-girl Eliza Doolittle.

| Pygmalion | |

|---|---|

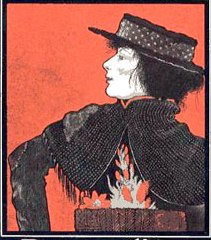

Illustration depicting Mrs Patrick Campbell as Eliza Doolittle | |

| Written by | George Bernard Shaw |

| Characters |

|

| Date premiered | 16 October 1913 |

| Place premiered | Hofburg Theatre in Vienna, Austria |

| Genre | Romantic comedy, social criticism |

| Setting | London, England |

Inspiration

editIn ancient Greek mythology, Pygmalion fell in love with one of his sculptures, which then came to life. The general idea of that myth was a popular subject for Victorian era British playwrights, including one of Shaw's influences, W. S. Gilbert, who wrote a successful play based on the story called Pygmalion and Galatea that was first presented in 1871. Shaw would also have been familiar with the musical Adonis and the burlesque version, Galatea, or Pygmalion Reversed.

Eliza Doolittle was inspired by Kitty Wilson, owner of a flower stall at Norfolk Street, Strand, in London. Wilson continued selling flowers at the stall until September, 1958. Her daughter, Betty Benton, then took over, but was forced to close down a month later when the City of London decreed that the corner was no longer "designated" for street trading.[1]

Shaw mentioned that the character of Professor Henry Higgins was inspired by several British professors of phonetics: Alexander Melville Bell, Alexander J. Ellis, Tito Pagliardini, but above all the cantankerous Henry Sweet.[2]

Shaw is also very likely to have known the life story of Jacob Henle, a professor at Heidelberg University, who fell in love with Elise Egloff, a Swiss housemaid, forcing her through several years of bourgeois education to turn her into an adequate wife. Egloff died shortly after their marriage. Her story inspired various literary works, including a play by Charlotte Birch-Pfeiffer and a novella by Gottfried Keller, comparing Henle with the Greek Pygmalion.[3]

First productions

editShaw wrote the play in early 1912 and read it to actress Mrs Patrick Campbell in June. She came on board almost immediately, but her mild nervous breakdown contributed to the delay of a London production. Pygmalion premièred at the Hofburg Theatre in Vienna on 16 October 1913, in a German translation by Shaw's Viennese literary agent and acolyte, Siegfried Trebitsch.[4][5]

Its first New York production opened on 24 March 1914 at the German-language Irving Place Theatre starring Hansi Arnstaedt as Eliza.[6] It opened in London on 11 April 1914, at Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree's His Majesty's Theatre, with Campbell as Eliza and Tree as Higgins, and ran for 118 performances.[7] Shaw directed the actors through tempestuous rehearsals, often punctuated by at least one of the two storming out of the theatre in a rage.[8]

Plot

editAct One

editA group of people are sheltering from the rain. Among them are the Eynsford-Hills, superficial social climbers eking out a living in "genteel poverty". We first see Mrs Eynsford-Hill and her daughter Clara; Clara's brother Freddy enters having earlier been dispatched to secure them a cab (which they can ill afford), but being rather timid and faint-hearted he has failed to do so. As he goes off once again to find a cab, he bumps into a flower girl, Eliza Doolittle. Her flowers drop into the mud of Covent Garden, the flowers she needs to survive in her poverty-stricken world.

They are soon joined by a gentleman, Colonel Pickering. While Eliza tries to sell flowers to the Colonel, a bystander informs her that another man is writing down everything she says. That man is Henry Higgins, a linguist and phonetician. Eliza worries that Higgins is a police officer and will not calm down until Higgins introduces himself.

It soon becomes apparent that he and Colonel Pickering have a shared interest in phonetics and an intense mutual admiration; indeed, Pickering has come from India specifically to meet Higgins, and Higgins was planning to go to India to meet Pickering. Higgins tells Pickering that he could pass off the flower girl as a duchess merely by teaching her to speak properly.

These words of bravado spark an interest in Eliza, who would love to make changes in her life and become more mannerly, even though to her it only means working in a flower shop. At the end of the act, Freddy returns after finding a taxi, only to find that his mother and sister have gone and left him with the cab. The streetwise Eliza takes the cab from him, using the money that Higgins tossed to her, leaving him on his own.

Act Two

editHiggins's house – the next day

As Higgins demonstrates his phonetics to Pickering, the housekeeper Mrs Pearce tells him that a young girl wants to see him. Eliza has shown up because she wants to talk like a lady in a flower shop. She tells Higgins that she will pay for lessons. He shows no interest, but she reminds him of his boast the previous day: he had claimed that he could pass her off as a duchess.

Pickering makes a bet with him on his claim and says that he will pay for her lessons if Higgins succeeds. She is sent off to have a bath. Mrs Pearce tells Higgins that he must behave himself in the young girl's presence, meaning he must stop swearing and improve his table manners, but he is at a loss to understand why she should find fault with him.

Alfred Doolittle, Eliza's father, appears, with the sole purpose of getting money out of Higgins, having no paternal interest in his daughter's welfare. He requests and received five pounds in compensation for the loss of Eliza, although Higgins, much amused by Doolittle's approach to morality, is tempted to pay ten.

Doolittle refuses; he sees himself as a member of the undeserving poor and means to go on being undeserving. With his intelligent mind untamed by education, he has an eccentric view of life. He is also aggressive, and Eliza, on her return, sticks her tongue out at him. He goes to hit her, but Pickering prevents him. The scene ends with Higgins telling Pickering that they really have a difficult job on their hands.

Act Three

editMrs Higgins's drawing room

editHiggins bursts in and tells his mother he has picked up a "common flower girl" whom he has been teaching. Mrs Higgins is unimpressed with her son's attempts to win her approval, because it is her 'at home' day and she is entertaining visitors. The visitors are the Eynsford-Hills. When they arrive, Higgins is rude to them.

Eliza enters and soon falls into talking about the weather and her family. While she is now able to speak in beautifully modulated tones, the substance of what she says remains unchanged from the gutter. She confides her suspicions that her aunt was killed by relatives, mentions that gin had been "mother's milk" to her aunt, and that Eliza's own father was "always more agreeable when he had a drop in".

Higgins passes off her remarks as "the new small talk", and Freddy is enraptured by Eliza. When she is leaving, he asks her if she is going to walk across the park, to which she replies, "Walk? Not bloody likely!" (This is the most famous line from the play and, for many years after the play's debut, use of the word 'bloody' was known as a pygmalion; Mrs Campbell was considered to have risked her career by speaking the line on stage.)[9]

After Eliza and the Eynsford-Hills leave, Higgins asks for his mother's opinion. She says the girl is not presentable and she is concerned about what will happen to her, but neither Higgins nor Pickering understands her concerns about Eliza's future. They leave feeling confident and excited about how Eliza will get on. This leaves Mrs Higgins feeling exasperated, and exclaiming, "Men! Men!! Men!!!"

Act Four

editHiggins's house – midnight

editHiggins, Pickering, and Eliza have returned from a ball. A tired Eliza sits unnoticed, brooding and silent, while Pickering congratulates Higgins on winning the bet. Higgins scoffs and declares the evening a "silly tomfoolery", thanking God it's over, and saying that he had been sick of the whole thing for the last two months. Still barely acknowledging Eliza, beyond asking her to leave a note for Mrs Pearce regarding coffee, the two retire to bed.

Higgins soon returns to the room, looking for his slippers, and Eliza throws them at him. Higgins is taken aback, and is at first completely unable to understand Eliza's preoccupation, which, aside from being ignored after her triumph, is the question of what she is to do now. When Higgins finally understands, he makes light of it, saying she could get married, but Eliza interprets this as selling herself like a prostitute. "We were above that at the corner of Tottenham Court Road."

Finally she returns her jewellery to Higgins, including the ring he had given her, which he throws into the fireplace with a violence that scares Eliza. Furious with himself for losing his temper, he damns Mrs Pearce, the coffee, Eliza, and finally himself, for "lavishing" his knowledge and his "regard and intimacy" on a "heartless guttersnipe", and retires in great dudgeon. Eliza roots around in the fireplace and retrieves the ring.

Act Five

editMrs Higgins's drawing room

The next morning Higgins and Pickering, perturbed by discovering that Eliza has walked out on them, call on Mrs Higgins to phone the police. Higgins is particularly distracted, since Eliza had assumed the responsibility of maintaining his diary and keeping track of his possessions, which causes Mrs Higgins to decry their calling the police as though Eliza were "a lost umbrella".

Doolittle is announced; he emerges dressed in splendid wedding attire and is furious with Higgins, who after their previous encounter had been so taken with Doolittle's unorthodox ethics that he had recommended him as the "most original moralist in England" to a rich American, a founder of Moral Reform Societies; the American had subsequently left Doolittle a pension worth three thousand pounds a year, as a consequence of which Doolittle feels intimidated into joining the middle class and marrying his missus.

Mrs Higgins observes that this at least settles the problem of who shall provide for Eliza, to which Higgins objects – after all, he paid Doolittle five pounds for her. Mrs Higgins informs her son that Eliza is upstairs, and explains the circumstances of her arrival, alluding to how marginalized and overlooked Eliza had felt the previous night. Higgins is unable to appreciate this, and sulks when told that he must behave if Eliza is to join them. Doolittle is asked to wait outside.

Eliza enters, at ease and self-possessed. Higgins blusters but Eliza is unshaken and speaks exclusively to Pickering. Throwing Higgins's previous insults back at him ("Oh, I'm only a squashed cabbage leaf"), Eliza remarks that it was only by Pickering's example that she learned to be a lady, which renders Higgins speechless.

Eliza goes on to say that she has completely left behind the flower girl she was, and that she couldn't utter any of her old sounds if she tried – at which point Doolittle emerges from the balcony, causing Eliza to emit her old sounds. Higgins is jubilant, jumping up and crowing over what he calls his victory. Doolittle explains his situation and asks if Eliza will come with him to his wedding. Pickering and Mrs Higgins also agree to go, and they leave, with Doolittle and Eliza to follow.

The scene ends with another confrontation between Higgins and Eliza. Higgins asks if Eliza is satisfied with the revenge she has brought thus far and if she will now come back, but she refuses. Higgins defends himself from Eliza's earlier accusation by arguing that he treats everyone the same, so she shouldn't feel singled out. Eliza replies that she just wants a little kindness, and that since he will never stoop to show her this, she will not come back, but will marry Freddy.

Higgins scolds her for such low ambitions: he has made her "a consort for a king." When she threatens to teach phonetics and offer herself as an assistant to Higgins's academic rival Nepommuck, Higgins again loses his temper and vows to wring her neck if she does so. Eliza realises that this last threat strikes Higgins at the very core and that it gives her power over him.

Higgins, for his part, is delighted to see a spark of fight in Eliza, rather than her erstwhile fretting and worrying. He remarks "I like you like this", and calls her a "pillar of strength". Mrs Higgins returns and she and Eliza depart for the wedding. As they leave, Higgins incorrigibly gives Eliza a list of errands to run, as though their recent conversation had not taken place. Eliza disdainfully tells him to do the errands himself. Mrs Higgins says that she'll get the items, but Higgins cheerfully tells her that Eliza will do it after all. Higgins laughs to himself at the idea of Eliza marrying Freddy as the play ends.

Critical reception

editThe play was well received by critics in major cities following its premières in Vienna, London, and New York. The initial release in Vienna garnered several reviews describing the show as a positive departure from Shaw's usual dry and didactic style.[10] The Broadway première in New York was praised in terms of both plot and acting, and the play was described as "a love story with brusque diffidence and a wealth of humour."[11] Reviews of the production in London were slightly less positive. The Telegraph noted that the play was deeply diverting, with interesting mechanical staging, although the critic ultimately found the production somewhat shallow and overly lengthy.[12] The Times, however, praised both the characters and the actors (especially Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree as Higgins and Mrs Patrick Campbell as Eliza) and the "unconventional" ending.[13][14]

Ending

editPygmalion was the most broadly appealing of all Shaw's plays. But popular audiences, looking for pleasant entertainment with big stars in a West End venue, wanted a "happy ending" for the characters they liked so well, as did some critics.[15] During the 1914 run, Tree sought to sweeten Shaw's ending to please himself and his record houses.[16] Shaw remained sufficiently irritated to add a postscript essay to the 1916 print edition, "'What Happened Afterwards",[17] for inclusion with subsequent editions, in which he explained precisely why it was impossible for the story to end with Higgins and Eliza getting married.

He continued to protect what he saw as the play's, and Eliza's, integrity by protecting the last scene. For at least some performances during the 1920 revival, Shaw adjusted the ending in a way that underscored the Shavian message. In an undated note to Mrs Campbell he wrote,

When Eliza emancipates herself – when Galatea comes to life – she must not relapse. She must retain her pride and triumph to the end. When Higgins takes your arm on 'consort battleship' you must instantly throw him off with implacable pride; and this is the note until the final 'Buy them yourself.' He will go out on the balcony to watch your departure; come back triumphantly into the room; exclaim 'Galatea!' (meaning that the statue has come to life at last); and – curtain. Thus he gets the last word; and you get it too.[18]

(This ending, however, is not included in any print version of the play.)

Shaw fought against a Higgins-Eliza happy-end pairing as late as 1938. He sent the 1938 film version's producer, Gabriel Pascal, a concluding sequence that he felt offered a fair compromise: a tender farewell scene between Higgins and Eliza, followed by one showing Freddy and Eliza happy in their greengrocery-cum-flower shop. Only at the sneak preview did he learn that Pascal had finessed the question of Eliza's future with a slightly ambiguous final scene in which Eliza returns to the house of a sadly musing Higgins and self-mockingly quotes her previous self announcing, "I washed my face and hands before I come, I did".

Different versions

editThere are two main versions of the play in circulation. One is based on the earlier version, first published in 1914; the other is a later version that includes several sequences revised by Shaw, first published in 1941. Therefore, different editions of the play omit or add certain lines. For instance, the Project Gutenberg version published online, which is transcribed from an early version, does not include Eliza's exchange with Mrs Pearce in Act II, the scene with Nepommuck in Act III, or Higgins' famous declaration to Eliza, "Yes, you squashed cabbage-leaf, you disgrace to the noble architecture of these columns, you incarnate insult to the English language! I could pass you off as the Queen of Sheba!" – a line so famous that it is now retained in nearly all productions of the play, including the 1938 film version of Pygmalion as well as in the stage and film versions of My Fair Lady.[19]

The co-director of the 1938 film, Anthony Asquith, had seen Mrs Campbell in the 1920 revival of Pygmalion and noticed that she spoke the line, "It's my belief as how they done the old woman in." He knew "as how" was not in Shaw's text, but he felt it added color and rhythm to Eliza's speech, and liked to think that Mrs Campbell had ad libbed it herself. Eighteen years later he added it to Wendy Hiller's line in the film.[8]

In the original play Eliza's test is met at an ambassador's garden party, offstage. For the 1938 film Shaw and co-writers replaced that exposition with a scene at an embassy ball; Nepommuck, the blackmailing translator spoken about in the play, is finally seen, but his name is updated to Aristid Karpathy – named so by Gabriel Pascal, the film's Hungarian producer, who also made sure that Karpathy mistakes Eliza for a Hungarian princess. In My Fair Lady he became Zoltan Karpathy. (The change of name was likely to avoid offending the sensibilities of Roman Catholics, as St. John Nepomuk was, ironically, a Catholic martyr who refused to divulge the secrets of the confessional.)

The 1938 film also introduced the famous pronunciation exercises "the rain in Spain stays mainly in the plain" and "In Hertford, Hereford, and Hampshire, hurricanes hardly ever happen".[20] Neither of these appears in the original play. Shaw's screen version of the play as well as a new print version incorporating the new sequences he had added for the film script were published in 1941. Many of the scenes that were written for the films were separated by asterisks, and explained in a "Note for Technicians" section.

Influence

editPygmalion remains Shaw's most popular play. The play's widest audiences know it as the inspiration for the highly romanticized 1956 musical and 1964 film My Fair Lady.

Pygmalion has transcended cultural and language barriers since its first production. The British Library contains "images of the Polish production...; a series of shots of a wonderfully Gallicised Higgins and Eliza in the first French production in Paris in 1923; a fascinating set for a Russian production of the 1930s. There was no country which didn't have its own 'take' on the subjects of class division and social mobility, and it's as enjoyable to view these subtle differences in settings and costumes as it is to imagine translators wracking their brains for their own equivalent of 'Not bloody likely'."[21]

Joseph Weizenbaum named his chatterbot computer program ELIZA after the character Eliza Doolittle.[22]

Notable productions

edit- 1914: Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree and Mrs Patrick Campbell at His Majesty's Theatre

- 1914: Philip Merivale and Mrs Patrick Campbell at three Broadway theatres [Park, Liberty, and Wallack's]

- 1920: C. Aubrey Smith and Mrs Patrick Campbell at the Aldwych Theatre

- 1926: Reginald Mason and Lynn Fontanne at the Guild Theatre (USA)

- 1936: Ernest Thesiger and Wendy Hiller at the Festival Theatre, Malvern

- 1937: Robert Morley and Diana Wynyard at the Old Vic Theatre

- 1945: Raymond Massey and Gertrude Lawrence at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre (USA)

- 1947: Alec Clunes and Brenda Bruce at the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith

- 1953: John Clements and Kay Hammond at the St James's Theatre, London

- 1965: Ian White and Jane Asher at the Watford Palace Theatre

- 1974: Alec McCowen and Diana Rigg at the Albery Theatre, London

- 1984: Peter O'Toole and Jackie Smith-Wood at the Shaftesbury Theatre, London

- 1987: Peter O'Toole and Amanda Plummer at the Plymouth Theatre (USA)

- 1992: Alan Howard and Frances Barber at the Royal National Theatre, London

- 1997: Roy Marsden and Carli Norris (who replaced Emily Lloyd early in rehearsals) at the Albery Theatre, London[23]

- 2007: Tim Pigott-Smith and Michelle Dockery at the Old Vic Theatre, London

- 2007: Jefferson Mays and Claire Danes at American Airlines Theatre (USA)

- 2010: Simon Robson and Cush Jumbo at the Royal Exchange Theatre, Manchester

- 2011: Rupert Everett (later Alistair McGowan) and Kara Tointon at the Garrick Theatre, London[24]

- 2011: Risteárd Cooper and Charlie Murphy at the Abbey Theatre, Dublin

- 2023 Bertie Carvel and Patsy Ferran at The Old Vic Theatre, London[25]

Adaptations

editStage

edit- My Fair Lady (1956), the Broadway musical by Lerner and Loewe (based on the 1938 film), starring Rex Harrison as Higgins and Julie Andrews as Eliza.

- Pygmalion (2024), a new stage adaption from Award Winning Writer/Director Chris Hawley, for Blackbox Theatre Company. The show toured the South of England during Summer 2024.

Film

edit- Pygmalion (1935), a German film adaptation by Shaw and others, starring Gustaf Gründgens as Higgins and Jenny Jugo as Eliza. Directed by Erich Engel.

- Hoi Polloi (1935), a short feature starring The Three Stooges comedy team. To win a bet, a professor attempts to transform the Stooges into gentlemen.

- Pygmalion (1937), a Dutch film adaptation, starring Johan De Meester as Higgins and Lily Bouwmeester as Elisa. Directed by Ludwig Berger.

- Pygmalion (1938), a British film adaptation by Shaw and others, starring Leslie Howard as Higgins and Wendy Hiller as Eliza.

- Kitty (1945), a film based on the novel of the same name by Rosamond Marshall (published in 1943). A broad interpretation of the Pygmalion story line, the film tells the rags-to-riches story of a young guttersnipe Cockney girl.

- My Fair Lady (1964), a film version of the musical starring Audrey Hepburn as Eliza and Rex Harrison as Higgins.

- The Opening of Misty Beethoven (1976), an American hardcore pornography film take-off starring Constance Money and Jamie Gillis.

- Educating Rita (1983): British comedy-drama film starring Michael Caine and Julie Walters

- Can't Buy Me Love (1987): a teenage romantic comedy reversing gender roles starring Patrick Dempsey and Amanda Peterson.

- She's All That (1999): a modern, teenage take on Pygmalion.

- Love Don't Cost a Thing (2003) a remake of the 1987 Can't Buy Me Love which is also an adaptation.

- The Duff (2015): based on the novel of the same name by Kody Keplinger, which in turn is a modern teenage adaption of Pygmalion.

- He's All That (2021): a Netflix Original movie that's a gender-swap retelling of the 1999 teen comedy; featuring Addison Rae and Rachael Leigh Cook .

Television

edit- A 1948 BBC TV version starring Margaret Lockwood as Eliza and Ralph Michael as Higgins.

- A 1963 Hallmark Hall of Fame production of Pygmalion, starring Julie Harris as Eliza and James Donald as Higgins.

- Pigmalião 70, a 1970 Brazilian telenovela, starring Sérgio Cardoso and Tônia Carrero.

- Pygmalion (1973), a BBC Play of the Month version starring James Villiers as Higgins and Lynn Redgrave as Eliza.

- Pygmalion (1981), a film version starring Twiggy as Eliza and Robert Powell as Higgins.

- Pygmalion (1983), an adaptation starring Peter O'Toole as Higgins and Margot Kidder as Eliza.

- The Makeover, a 2013 Hallmark Hall of Fame modern adaptation of Pygmalion, starring Julia Stiles and David Walton and directed by John Gray.[26][27]

- Selfie, a 2014 television sitcom on ABC, starring Karen Gillan and John Cho.

- Classic Alice, a webseries, aired a 10-episode adaptation on YouTube, starring Kate Hackett and Tony Noto in 2014.

- Totalmente Demais, a 2015 Brazilian telenovela, starring Juliana Paes, Marina Ruy Barbosa, and Fábio Assunção.

The BBC has broadcast radio adaptations at least twice, in 1986 directed by John Tydeman and in 2021 directed by Emma Harding.

Non–English language

- Pigmalió, an adaptation by Joan Oliver into Catalan. Set in 1950s Barcelona, it was first staged in Sabadell in 1957 and has had other stagings since.

- Ti Phulrani, an adaptation by Pu La Deshpande in Marathi. The plot follows Pygmalion closely but the language features are based on Marathi.

- Santu Rangeeli, an adaptation by Madhu Rye and Pravin Joshi in Gujarati.

- سيدتي الجميلة (Sayydati El-Gameela, My Fair Lady), a 1969 Egyptian stage adaptation of My Fair Lady starring the comedy duo and then married couple, Fouad el-Mohandes and Shwikar. It was performed and filmed for television at the Alexandria Opera House.[28]

- A 1996 television play in Polish, translated by Kazimierz Piotrowski, directed by Maciej Wojtyszko and performed at Teatr Telewizji (Polish Television studio in Warsaw) by some of the top Polish actors at the time. It has been aired on national TV numerous times since its TV premiere in 1998.

- A 2007 adaptation by Aka Morchiladze and Levan Tsuladze in Georgian performed at the Marjanishvili Theatre in Tbilisi.

- Man Pasand, a 1980 Hindi movie directed by Basu Chatterjee.

- Ogo Bodhu Shundori, a 1981 Bengali comedy film starring Uttam Kumar directed by Salil Dutta.

- My Young Auntie, a 1981 Hong Kong action film directed by Lau Kar-Leung.

- Laiza Porko Sushi, a Papiamentu adaptation from writer and artist May Henriquez.

- Gönülcelen, a Turkish series starring Tuba Büyüküstün and Cansel Elcin.

- Δύο Ξένοι, a Greek series starring Nikos Sergianopoulos and Evelina Papoulia.

- Pigumarion (in Japanese), starring Tomohiro Ichikawa as Henry Higgins and Shiho Takano as Eliza Doolittle was performed in 2011 at the Owlspot Theater in Tokyo.

- Pigumarion (in Japanese), starring Takahiro Hira as Henry Higgins and Satomi Ishihara as Eliza Doolittle was performed in 2013 at the New National Theater in Tokyo.

In popular culture

editFilms

edit- The First Night of Pygmalion (1972), a play depicting the backstage tensions during the first British production.

- Willy Russell's 1980 stage comedy Educating Rita and the subsequent film adaptation are similar in plot to Pygmalion.[29]

- Trading Places (1983), a film starring Eddie Murphy and Dan Aykroyd.[30]

- Pretty Woman (1990), a film starring Julia Roberts and Richard Gere.[31]

- Mighty Aphrodite (1995), a film directed by Woody Allen.[32]

- She's All That (1999), a film starring Rachael Leigh Cook and Freddie Prinze Jr.[33]

- Confessions of a Teenage Drama Queen (2004), a film starring Lindsay Lohan where she auditions for a modernized musical version of Pygmalion called "Eliza Rocks".[34]

- Ruby Sparks (2012), a film written by and starring Zoe Kazan explores a writer (played by Paul Dano) who falls in love with his own fictional character who becomes real.[35]

Television

edit- Moonlighting's second-season episode "My Fair David" (1985) is inspired by the movie My Fair Lady, in a plot where Maddie Hayes makes a bet with David Addison consisting in making him softer and more serious with work. She is her Henry Higgins, while he is put in the Eliza Doolittle position, as the funny, clumsy, bad-mannered part of the relationship.

- The Man from U.N.C.L.E.'s third-season episode "The Galatea Affair" (1966) is a spoof of My Fair Lady. A crude barroom entertainer (Joan Collins) is taught to behave like a lady. Noel Harrison, son of Rex Harrison, star of the My Fair Lady film, is the guest star.

- In The Beverly Hillbillies episode "Pygmalion and Elly", Sonny resumes his high-class courtship of Elly May by playing Julius Caesar and Pygmalion.

- In The Andy Griffith Show season 4 episode "My Fair Ernest T. Bass", Andy and Barney attempt to turn the mannerless Ernest T. Bass into a presentable gentleman. References to Pygmalion abound: Bass' manners are tested at a social gathering, where he is assumed by the hostess to be a man from Boston. Several characters comment "if you wrote this into a play nobody'd believe it."

- In Doctor Who, the character of Leela is loosely based on Eliza Doolittle. She was a regular in the programme from 1977 to 1978, and later reprised in audio dramas from 2003 to present. In Ghost Light, the character of Control is heavily based upon Eliza Doolittle, with Redvers Fenn-Cooper in a similar role as Henry Higgins; the story also features reference to the "Rain in Spain" rhyme and the Doctor referring to companion Ace as "Eliza".

- In the Remington Steele season 2 episode "My Fair Steele", Laura and Steele transform a truck stop waitress into a socialite to flush out a kidnapper. Steele references the 1938 movie Pygmalion and My Fair Lady, and references the way in which Laura has "molded" him into her fictional creation.

- In the Magnum, P.I. episode "Professor Jonathan Higgins" of Season 5, Jonathan Higgins tries to turn his punk rocker cousin into a high society socialite. Higgins references Pygmalion in the episode.

- The Simpsons episode titled "Pygmoelian" is inspired by Pygmalion, in which ugly barman Moe Szyslak has a facelift. It was also parodied to a heavier extent in the episode "My Fair Laddy", where the character being changed is uncouth Scotsman Groundskeeper Willie, with Lisa Simpson taking the Henry Higgins role.

- The Family Guy episode "One If By Clam, Two If By Sea" involves a subplot with Stewie trying to refine Eliza Pinchley, his new Cockney-accented neighbor, into a proper young lady. He makes a bet with Brian that he can improve Eliza's vocabulary and get her to speak without her accent before her birthday party. Includes "The Life of the Wife", a parody of the song "The Rain in Spain" (from My Fair Lady). The voice of Stewie was in fact originally based on that of Rex Harrison.

- The plot of the Star Trek: Voyager episode "Someone to Watch Over Me" is loosely based on Pygmalion, with the ship's holographic doctor playing the role of Higgins to the ex-Borg Seven of Nine.

- In the Boy Meets World episode "Turnaround", Cory and Shawn learn about Pygmalion in class, paralleling their attempt with Cory's uncool date to the dance.

- The iCarly episode "iMake Sam Girlier" is loosely based on Pygmalion.[citation needed]

- The Season 7 King of the Hill episode "Pigmalion" describes an unhinged local pig magnate who attempts to transform Luanne into the idealized woman of his company's old advertisements.

- In The King of Queens episode "Gambling N'Diction", Carrie tries to lose her accent for a job promotion by being taught by Spence. The episode was renamed to "Carrie Doolittle" in Germany.

- In 2014, ABC debuted a romantic situational comedy titled Selfie, starring Karen Gillan and John Cho. It is a modern-day adaptation that revolves around an image-obsessed woman named Eliza Dooley (Gillan) who comes under the social guidance of marketing image guru Henry Higgs (Cho).

- In the Malaysian drama Nur, Pygmalion themes are evident. The lives of a pious, upstanding man and a sex worker are considered within the context of Islam, societal expectations and norms.

- In Will & Grace season 5, a 4-episode arc entitled "Fagmalion" has Will and Jack take on the project of turning unkempt Barry, a newly out gay man, into a proper member of gay society.

References

edit- ^ "Drury Lane: Eliza Moves Away", Newsweek, Oct. 13, 1958

- ^ George Bernard Shaw, Androcles and the Lion: Overruled : Pygmalion (New York City: Brentano's, 1918), page 109. Archived 14 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine (Note: Alexander M. Bell's first wife was named Eliza.)

- ^ Robinson, Victor, M.D. (1921). The Life of Jacob Henle. New York: Medical Life Co.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Theses & Conference Papers". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- ^ Shaw, Bernard, edited by Samuel A. Weiss (1986). Bernard Shaw's Letters to Siegfried Trebitsch. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1257-3, p.164.

- ^ "Herr G.B. Shaw at the Irving Place." Archived 26 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times Archived 23 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine 25 March 1914. In late 1914 Mrs Campbell took the London company to tour the United States, opening in New York at the Belasco Theatre.

- ^ Laurence, Dan, ed. (1985). Bernard Shaw: Collected Letters, 1911–1925. New York: Viking. p. 228. ISBN 0-670-80545-9.

- ^ a b Dent, Alan (1961). Mrs. Patrick Campbell. London: Museum Press Limited.

- ^ The Truth About Pygmalion by Richard Huggett, 1969 Random House, pp. 127–128

- ^ "The Modest Shaw Again: Explains in His Shrinking Way Why "Pygmalion" Was First Done in Berlin;- Critics Like It". The New York Times. 23 November 1913. ProQuest 97430789.

- ^ "Shaw's 'Pygmalion' Has Come to Town: With Mrs. Campbell Delightful as a Galatea from Tottenham Court Road – A Mildly Romantic G. B. S. – His Latest Play Tells a Love Story with Brusque Diffidence and a Wealth of Humor". The New York Times. 13 October 1914. ProQuest 97538713.

- ^ "Pygmalion, His Majesty's Theatre, 1914, review". The Telegraph. 11 April 2014. Archived from the original on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ^ "The Story Of "Pygmalion."". The Times. 19 March 1914. Archived from the original on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2016 – via Gale.

- ^ "Viewing 1914/3/19 Page 11 - The Story Of "Pygmalion."". www.thetimes.co.uk. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ Evans, T.F. (ed.) (1997). George Bernard Shaw (The Critical Heritage Series). ISBN 0-415-15953-9, pp. 223–30.

- ^ "From the Point of View of A Playwright," by Bernard Shaw, collected in Herbert Beerbohm Tree, Some Memories of Him and His Art, Collected by Max Beerbohm (1919). London: Hutchinson, p. 246. Versions at Text Archive Internet Archive

- ^ Shaw, G.B. (1916). Pygmalion. New York: Brentano. Sequel: What Happened Afterwards. Archived 16 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine Bartleby: Great Books Online. Archived 30 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Instinct of An Artist: Shaw and the Theatre." Archived 8 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine Catalog for "An Exhibition from The Bernard F. Burgunder Collection," 1997. Cornell University Library Archived 26 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Project Gutenberg E-text of Pygmalion, by George Bernard Shaw". Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ Pascal, Valerie, The Disciple and His Devil, McGraw-Hill, 1970. p. 83."

- ^ Summers, Anne (2 July 2001). "The lesson of a Polish production of 'Pygmalion'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 18 March 2017.

- ^ Markoff, John (13 March 2008), "Joseph Weizenbaum, Famed Programmer, Is Dead at 85", The New York Times, archived from the original on 1 April 2011, retrieved 7 January 2009

- ^ British Theatre Guide (1997)

- ^ Tointon's indisposition on 25 August 2011 enabled understudy Rebecca Birch to make her West End début in a leading role (insert to Garrick Theatre programme for Pygmalion).

- ^ Cashell, Eleni (12 April 2023). "PYGMALION revival to star Bertie Carvel and Patsy Ferran". London Box Office. London, UK.

- ^ "Julia Stiles Stars in The Makeover". Archived from the original on 1 January 2013. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ^ "IMDb: The Makeover". IMDb. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ "مسرحية سيدتي الجميلة | فؤاد المهندس - شويكار - حسن مصطفي | كاملة". YouTube. 5 September 2023.

- ^ "Willy Russell: Welcome". Archived from the original on 15 July 2007. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

- ^ "Is 'Trading Places' the ultimate New Year's Eve movie of the '80s?". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved 20 June 2021.[dead link]

- ^ "Pretty Woman vs. Pygmalion Essay - 1024 Words | Bartleby". www.bartleby.com. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ "Mira Sorvino: 'I'm not sure I'd take the Mighty Aphrodite role now'". The Guardian. 30 October 2014. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "She's All That movie review & film summary (1999) | Roger Ebert". rogerebert.com. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ Kehr, Dave (20 February 2004). "FILM REVIEW; A Teenager Struggles to Star in Her New Town". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ "Pygmalion was muse behind 'Ruby Sparks'". Los Angeles Times. 14 July 2012. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

External links

edit- Pygmalion at Standard Ebooks

- Pygmalion at the Internet Broadway Database

- Pygmalion stories & art: "successive retellings of the Pygmalion story after Ovid's Metamorphoses

- Pygmalion at Project Gutenberg

- Pygmalion public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Shaw's Pygmalion was in a different class 2014 Irish Examiner article by Dr. R. Hume

- "Bernard Shaw Snubs England and Amuses Germany." The New York Times, 30 November 1913. This article quotes the original script at length ("translated into the vilest American": Letters to Trebitsch, p. 170), including its final lines. Its author, too, hopes for a "happy ending": that after the curtain Eliza will return bearing the gloves and tie.