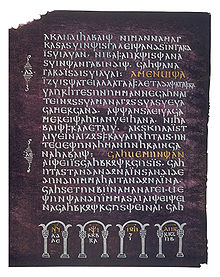

Purple parchment or purple vellum refers to parchment dyed purple; codex purpureus refers to manuscripts written entirely or mostly on such parchment. The lettering may be in gold or silver. Later[when?] the practice was revived for some especially grand illuminated manuscripts produced for the emperors in Carolingian art and Ottonian art, in Anglo-Saxon England and elsewhere. Some just use purple parchment for sections of the work; the 8th-century Anglo-Saxon Stockholm Codex Aureus alternates dyed and un-dyed pages.

It was at one point supposedly restricted for the use of Roman or Byzantine emperors, although in a letter of Saint Jerome of 384, he "writes scornfully of the wealthy Christian women whose books are written in gold on purple vellum, and clothed with gems".[1]

Examples

editThe Purple Uncials or the Purple Codices is a well-known group of these manuscripts, all 6th-century New Testament Greek manuscripts:

- Codex Purpureus Petropolitanus N (022)

- Sinope Gospels O (023) (illuminated)

- Rossano Gospels Σ (042) (illuminated)

- Codex Beratinus Φ (043) (illuminated)

- Uncial 080

Two other purple New Testament Greek manuscripts are minuscules:

- Minuscule 565 known as the Empress Theodora's Codex

- Minuscule 1143 known as Beratinus 2

There is a 9th-century lectionary:

- Codex Neapolitanus, former Codex Vindobonensis 2

Another six New Testament purple manuscripts are in Latin (with corresponding sigla a, b, e, f, i, j). Besides some scattered fragments, they are held mainly in: Brescia, Naples, Sarezzano, Trent and Vienna. Three of these use Vetus Latina texts:

- Codex Vercellensis

- Codex Veronensis

- Codex Palatinus

- Codex Brixianus

- Codex Purpureus Sarzanensis

- Codex Vindobonensis Lat. 1235

There is also one Gothic purple codex – the Codex Argenteus (illuminated).

There is a purple manuscript of part of the Septuagint:

- Vienna Genesis (illuminated)

Other illuminated manuscripts include the Godescalc Evangelistary of 781–3, the Vienna Coronation Gospels (early 9th century) and a few pages of the 9th-century La Cava Bible from the Kingdom of Asturias. Anglo-Saxon examples include a lost 7th-century Gospels commissioned by Saint Wilfrid.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Needham, 21

References

edit- Needham, Paul (1979). Twelve Centuries of Bookbindings 400–1600. Pierpont Morgan Library/Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-192-11580-5.

External links

edit- Media related to Purple parchments at Wikimedia Commons

- The World of Bede

- at the Encyclopedia of Textual Criticism