The Raid on Dunkirk of 7 July 1800 was an attack by a British Royal Navy force on the well-defended French anchorage of Dunkirk in the English Channel during the French Revolutionary Wars. French naval forces had been blockaded in their harbours during the conflict, and often the only method of attacking them was through fireships or "cutting-out" expeditions, in which boats would carry boarding parties into the harbour at night, seize ships at anchor and bring them out. The attack on Dunkirk was a combination of both of these types of operation, aimed at a powerful French frigate squadron at anchor in Dunkirk harbour. The assault made use of a variety of experimental weaponry, some of which was tested in combat for the first time with mixed success.

| Raid on Dunkirk | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the naval operations during the War of the Second Coalition | |||||||

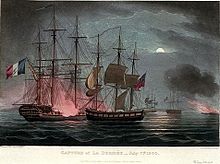

Capture of La Desirée, Thomas Whitcombe | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

2 frigates 1 sloop 4 fireships | 4 frigates | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

18 killed and wounded 4 fireships destroyed |

100 killed and wounded 1 frigate captured | ||||||

Although assault by the heavily armed sloop HMS Dart proved successful, the fireships achieved little and various other British craft involved in the operation had little effect on the eventual outcome. The French response was disorganised and ineffectual, losing one frigate captured. Three others were almost destroyed, only escaping by cutting their anchor cables and fleeing into the coastal shoals where they ran aground. Although all three frigates were refloated and returned to service, the operation had cost the French heavy casualties. The British force suffered minimal losses, although the exact totals are uncertain. Many of the British officers involved were highly praised and rewarded with promotions and prize money.

Background

editBy the late French Revolutionary Wars (1793–1802), a string of victories at sea ensured that the Royal Navy was dominant. The French Navy in particular had suffered heavy losses, and in Northern European waters had been forced back into its own harbours by British blockade squadrons.[1] Although large ports were watched by fleets of ships of the line, small ports had their own blockade squadrons too, including the shallow French ports on the English Channel. These harbours could not accommodate ships of the line but were well situated for frigates that attacked shipping in British waters whenever they could escape the blockade. One such port was Dunkirk in French Flanders, which contained a squadron of four French frigates: the 44-gun Poursuivante under Commodore Jean-Joseph Castagnier, the 40-gun Carmagnole and the 36-gun Désirée and Incorruptible. Dunkirk was well defended, with gun batteries and gunboats overlooking the harbour. In addition, the port was surrounded by complicated coastal shoals into which the frigates could retreat if attacked.[2]

The port was closely watched, it was determined that an attack by a squadron of smaller vessels on the frigates stood a chance of success and a number of ships were instructed to gather off the coast. Captain Henry Inman of the frigate HMS Andromeda, had overall command; the force included HMS Nemesis under Captain Thomas Baker and 15 smaller vessels.[3] The small craft included four fireships, small brigs designed to operate as minor warships until such time as they were deemed expendable in an attack on an anchored target, and the sloop HMS Dart under Commander Patrick Campbell. Dart was a highly unusual ship: her size meant that she was unrated even though her armament included thirty 32-pounder carronades. The carronades were mounted to a new design that minimised recoil and made them faster and easier to load.[4]

The squadron had assembled by 17 June 1800, but for ten days the winds and tides prevented the operation.[5] The French prepared for any attack by anchoring their frigates in a line running across the harbour from east to west, supported by gunboats that patrolled the harbour. The westernmost ships were positioned so that they could make their escape into the channels of the Braak Sands if they came under concerted attack.[6] Inman knew that his largest ships, Andromeda and Nemesis, would prove liabilities in the narrow harbour. Both remained offshore, their crews dispersed into the smaller ships that would lead the attack, including the fireships HMS Wasp, HMS Falcon, HMS Comet, and HMS Rosario, and the brigs HMS Biter and HMS Boxer, and the hired ships Kent, Ann and Vigilant (on which Inman sailed). The entire squadron was led by Dart, under Campbell, whose target was the eastern end of the French line, the frigate Désirée.[4]

Battle

editInman's squadron entered Dunkirk harbour on the late evening of 7 July 1800, Dart slowly leading the way and the rest of the squadron sailing in a line behind the heavily armed sloop. Inman had crewed the hired ships Vigilant and Nile with men impressed from smugglers ships, and these men acted as guides for the British force.[7] At midnight the shapes of the French frigates appeared from the darkness ahead and Dart gradually passed down their line, until a hail from one of the frigates demanded to know where Dart had come from. A French-speaking officer replied "De Bordeaux" ("from Bordeaux") and was then asked what the little ships behind Dart were, to which the officer replied "Je ne sais pas" ("I do not know"). Apparently satisfied with this reply, there were no more questions from the frigate and Dart continued its passage until it came alongside the last French frigate but one.[4] Lookouts on this ship recognised the shape of the strange vessel that had appeared out of the night and immediately opened fire, to which Dart swiftly responded. Campbell knew that his heavy carronades were devastating at close range, and had ordered them to be double-shotted, meaning that each carronade carried twice the ordinary number of missiles. The effect was immediate, with heavy casualties and severe damage inflicted on the French vessel. The fast loading abilities of the carronades allowed the sloop's 15 guns to keep up a steady fire as Dart swept on to the last ship in line, Désirée.[3]

Using an anchor to steady his ship, Campbell placed Dart alongside the French frigate, with his bows between the French ship's masts. This allowed a boarding party led by Lieutenant James M'Dermeit to leap aboard Désirée and drive the French off the frigate's deck in hand-to-hand combat. M'Dermeit was wounded in the fighting, and called across for reinforcements as the French regrouped in the stern of the ship. Campbell used his anchors to swing Dart alongside the French frigate and a second boarding party under Lieutenant William Isaac Pearce charged aboard, routing the French reinforcements that were emerging from below decks.[7] With the upper deck secure, Pearce severed the anchor cables, steered Désirée out of the harbour and over the sandbars that were rapidly being exposed by the receding tide. With his target captured, Campbell turned Dart towards the second British attack, against the head of the French line.[4]

As Dart and Désirée fought at the southern end of the line, the British fireships attacked the van. The fireships had been stripped of all useful materials and been converted into their original role. Small crews of volunteers set alight to the vessels and all four bore down on the three northern French ships with supporting fire coming from Dart and the brigs. The smaller vessels, accompanied by a number of ship's boats from the British frigates outside the harbour, attended the fireships and removed their crews once they were alight.[7] Although all four fireships were well-handled, the French were prepared for the tactic and the squadron severed its anchor cables and sailed into the channels around the Braak Sands. This manoeuvre took them past Biter and Boxer and also exposed them to continued fire from Dart, but, despite the damage, all three made the safety of the channel, into which the British could not follow without fear of grounding.[7] One of the French ships did become stuck at low tide, but out of the range of the British ships and it suffered no serious damage. The fireships drifted aimlessly before exploding uselessly, succeeding only in wounding two British sailors whose boat was too close to Comet.[8] While the frigates and fireships fought, a host of small French gunboats emerged from Dunkirk and were met by the hired ships, armed as brigs. In a sharp engagement the hired ships lost four wounded but successfully held back the gunboats during the battle.[9]

Aftermath

editWith his principal targets out of reach, Inman called off the attack during the early morning and withdrew his ships. He had lost one man killed and 17 wounded, all but six of the latter coming from Dart (some sources only record the men wounded on Dart in the total).[3] French casualties were far more severe, with more than 100 men killed or wounded, mostly on Désirée, which had taken the brunt of Dart's attack. Recognising that he had no room for prisoners and that many of the French wounded required urgent treatment, Inman ordered the wounded men to be sent back to Dunkirk, although it appears this amnesty was subsequently extended to all the prisoners.[8] By midday on 8 July 1800 the British squadron had returned to its position off the coast while Désirée was sent to Britain, later commissioned in the Royal Navy as HMS Desiree under the command of Captain Inman. Prize money was paid for the captured frigate,[10] but head money, an award made for enemy servicemen killed, wounded or captured, was not paid, probably due to the return of the prisoners. For their services, Commander Campbell and Lieutenant M'Dermeit were promoted, the former transferring from Dart into the much smaller sixth rate HMS Ariadne. The French ships returned from the Braak Sand during the morning and repairs were conducted in Dunkirk.[8] In 1847 the Admiralty awarded the Naval General Service Medal with clasp "Capture of the Desiree" to all surviving claimants from the action.[11]

Notes

edit- ^ Gardiner, p. 136

- ^ Clowes, p. 531

- ^ a b c Gardiner, p. 137

- ^ a b c d James, p. 42

- ^ James, p. 41

- ^ "No. 15274". The London Gazette. 8 July 1800. p. 782.

- ^ a b c d "No. 15274". The London Gazette. 8 July 1800. p. 783.

- ^ a b c James, p. 43

- ^ Clowes, p. 532

- ^ "No. 15298". The London Gazette. 30 September 1800. p. 1135.

- ^ "No. 20939". The London Gazette. 26 January 1849. p. 238.

Bibliography

edit- Clowes, William Laird (1997) [1900]. The Royal Navy, A History from the Earliest Times to 1900, Volume IV. Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-013-2.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (2001) [1996]. Nelson Against Napoleon. Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-86176-026-4.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume 3, 1800–1805. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-907-7.