Rat-baiting is a blood sport that involves releasing captured rats in an enclosed space with spectators betting on how long a dog, usually a terrier and sometimes referred to as a ratter, takes to kill the rats. Often, two dogs competed, with the winner receiving a cash prize. It is now illegal in most countries.

History

editIn 1835, the Parliament of the United Kingdom implemented an act called the Cruelty to Animals Act 1835, which prohibited the baiting of some animals, such as the bull, bear, and other large mammals. However, the law was not enforced for rat baiting and competitions came to the forefront as a gambling sport. It was very popular in Ireland even before 1835, because of the limited space in larger cities, Dublin and Belfast especially. Some families sought to profit from the large numbers of vermin plaguing the cities and countryside. Many countries adopted this sport after 1835, with England having one of the largest participation rates.[citation needed] At one time, London even had at least 70 rat pits.[1]

Atmosphere

editJames Wentworth Day, a follower of the sport of rat baiting, described his experience and the atmosphere at one of the last old rat pits in London during those times.

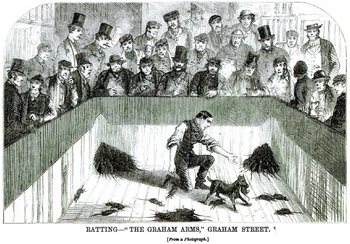

This was a rather dirty, small place, in the middle of the Cambridge Circus, London. You went down a rotten wooden stair and entered a large, underground cellar, which was created by combining the cellars of two houses. The cellar was full of smoke, stench of rats, dogs, and dirty human beings, as well. The stale smell of flat beer was almost overpowering. Gas lights illuminated the centre of the cellar, a ring enclosed by wood barriers similar to a small Roman circus arena, and wooden bleachers, arranged one over the other, rose stepwise above it nearly to the ceiling. This was the pit for dog fights, cockfights, and rat killing. A hundred rats were put in it; large wagers went back and forth on whose dog could kill the most rats within a minute. The dogs worked in exemplary fashion, a grip, a toss, and it was all over for the rat. With especially skillful dogs, two dead rats flew through the air at the same time ...

Rules

editThe officials included a referee and timekeeper. Pits were sometimes covered above with wire mesh or had additional security devices installed on the walls to prevent the rats from escaping. Rules varied from match to match.

In one variation, a weight handicap was set for each dog. The competing dog had to kill as many rats as the number of pounds the dog weighed, within a specific, preset time.[3] The prescribed number of rats was released and the dog was put in the ring. The clock started the moment the dog touched the ground. When the dog seized the last rat, his owner grabbed it and the clock stopped.

Rats that were thought still to be alive were laid out on the table in a circle before the referee. The referee then struck the animal three times on the tail with a stick. If a rat managed to crawl out of the circle, it was considered to be alive.[3] Depending on the particular rules for that match, the dog may be disqualified or have to go back in the ring with these rats and kill them. The new time was added to the original time.

A combination of the quickest time, the number of rats, and the dog's weight decided the victory. A rate of five seconds per rat killed was considered quite satisfactory; 15 rats in a minute was an excellent result.

Cornered rats will attack and can deliver a very painful bite. Not uncommonly, a ratter (rat-killing dog) was left with only one eye in its retirement.

Rat-catcher

editBefore the contest could begin, the capture of potentially thousands of rats was required. The rat catcher would be called upon to fulfill this requirement. Jack Black, a rat catcher from Victorian England[4] supplied live rats for baiting.

Technique

editFaster dogs were preferred. They would bite once. The process was described as "rather like a sheepdog keeping a flock bunched to be brought out singly for dipping," where the dog would herd the rats together, and kill any rats that left the pack with a quick bite.[3]

Breeds

editThe ratting dogs were typically working terrier breeds, which included the bull and terrier, Bull Terrier, Bedlington Terrier, Fox Terrier, Jack Russell Terrier, Rat Terrier, Black and Tan Terrier,[5][6] Manchester Terrier, Yorkshire Terrier, and Staffordshire Bull Terrier.[7] The degree of care used in breeding these ratters is clear in their pedigrees, with good breeding leading to increased business opportunities. Successful breeders were highly regarded in those times. In modern times, the Plummer Terrier is considered a premiere breed for rat-catching.

Billy

editA celebrated bull and terrier named "Billy"[8][9] weighing about 12 kg (26 lb), had a proud fighting history and his pedigree reflects the build-up over the years. The dog was owned by Charles Dew and was bred by a breeder James Yardington. On the paternal side is "Old Billy" from the kennel of John Tattersal from Wotton-under-Edge, Gloucestershire, and was descended from the best line of all Old English Bulldogs. On the maternal side is "Yardington's Sal" descended from the Curley line. The pedigree of all these dogs can be traced back more than 40 years and numerous old accounts exist about them.[citation needed]

The October 1822, edition of The Sporting Magazine provided descriptions of two rat pit matches with Billy, quoted as:

Thursday night, Oct. 24, at a quarter before eight o'clock, the lovers of rat killing enjoyed a feast of delight in a prodigious raticide at the Cockpit, Westminster. The place was crowded. The famous dog Billy, of rat-killing notoriety, 26 lb. weight, was wagered, for 20 sovereigns, to kill 100 rats in 12 minutes. The rats were turned out loose at once in a 12-foot square, and the floor whitened so that the rats might be visible to all. The set-to began, and Billy exerted himself to the utmost. At four minutes and three-quarters, as the hero's head was covered with gore, he was removed from the pit, and his chaps being washed, he lapped some water to cool his throat. Again he entered the arena, and in vain did the unfortunate victims labour to obtain security by climbing against the sides of the pit, or by crouching beneath the hero. By twos and threes, they were caught, and soon their mangled corpses proved the valour of the victor. Some of the flying enemy, more valiant than the rest, endeavoured by seizing this Quinhus Flestrum of heroic dogs by the ears, to procure a respite, or to sell their life as dearly as possible; but his grand paw soon swept off the buzzers, and consigned them to their fate. At seven minutes and a quarter, or according to another watch, for there were two umpires and two watches, at seven minutes and seventeen seconds, the victor relinquished the glorious pursuit, for all his foes lay slaughtered on the ensanguined plain. Billy was then caressed and fondled by many; the dog is estimated by amateurs as a most dextrous animal; he is, unfortunately, what the French Monsieurs call borg-ne, that is, blind of an eye.-This precious organ was lost to him some time since by the intrepidity of an inimical rat, which as he had not seized it in a proper place, turned round on its murderer, and reprived him by one bite of the privilege of seeing with two eyes in future. The dog BILLY, of rat-killing notoriety, on the evening of the 13th instant, again exhibited his surprising dexterity; he was wagered to kill one hundred rats within twelve minutes; but six minutes and 25 seconds only elapsed, when every rat lay stretched on the gory plain, without the least symptom of life appearing.' Billy was decorated with a silver collar, and a number of ribband bows, and was led off amidst the applauses of the persons assembled.

Billy's best competition results are:

| Date | Rats killed | Time | Time per rat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1820–??-?? | 20 | 1 minute, 11 seconds | 3.6 seconds | |

| 1822-09-03 | 100 | 8 minutes, 45 seconds | 5.2 seconds | |

| 1822-10-24 | 100 | 7 minutes, 17 seconds | 4.4 seconds | |

| 1822-11-13 | 100 | 6 minutes, 25 seconds | 3.8 seconds | |

| 1823-04-22 | 100 | 5 minutes, 30 seconds | 3.3 seconds | * Record |

| 1823-08-05 | 120 | 8 minutes, 20 seconds | 4.1 seconds |

Billy's career was crowned on 22 April 1823, when a world record was set with 100 rats killed in five and a half minutes. This record stood until 1862 when it was claimed by another ratter named "Jacko". Billy continued in the rat pit until old age, reportedly with only one eye and two teeth remaining.[8][9]

Jacko

editAccording to the Sporting Chronicle Annual, the world record in rat killing is held by a black and tan bull and terrier named "Jacko", weighing about 13 lb and owned by Jemmy Shaw.[10][8][9] Jacko had these contest results:

| Date | Rats killed | Time | Time per rat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1861-08-08 | 25 | 1 minute, 28 seconds | 3.5 seconds | |

| 1862-07-29 | 60 | 2 minutes, 42 seconds | 2.7 seconds | * Record |

| 1862-05-01 | 100 | 5 minutes, 28 seconds | 3.3 seconds | * Record |

| 1862-06-10 | 200 | 14 minutes, 37 seconds | 4.4 seconds | |

| 1862-05-01 | 1000 | in less than 100 minutes | 6.0 seconds |

Jacko set two world records, the first on 29 July 1862, with a killing time of 2.7 seconds per rat and the second on 1 May 1862, with his fight against 100 rats, where Jacko worked two seconds faster than the previous world record holder "Billy". The feat of killing 1,000 rats took place over ten weeks, with 100 rats being killed each week ending on 1 May 1862.

Tiny the Wonder

editTiny the Wonder was a famous mid-19th century English Toy Terrier (Black & Tan) that could kill 200 rats in an hour,[11][12] which he achieved twice, on 28 March 1848 and 27 March 1849, with time to spare.[13] For a period of time Tiny maintained the record for killing 300 rats in under 55 minutes.[14] Tiny only weighed five and a half pounds with a neck so small, a woman's bracelet could be used as a dog collar. From 1848 to 1849, Tiny was owned by Jemmy Shaw, the landlord of the Blue Anchor Tavern at 102 Bunhill Row, St. Luke's, London Borough of Islington; the pub is now named the Artillery Arms.[15] Tiny was a star attraction at the Blue Anchor Tavern, with crowds gathering to watch the action in the rat pit. Shaw preferred to acquire the rats from Essex as opposed to sewer rats to decrease potential health risks to Tiny. Shaw was able to keep up to 2,000 rats at his establishment.[13] This is a commentary about Tiny from a poster published from those times:[16]

- "The 5 1/2 pounds of black and tan fury! This extraordinary Black and Tan has won 50 interesting events, including the following matches: 2 matches of 6 rats when he weighed 4 1/2 pounds, 20 matches of 12 rats at 5 pounds of weight, 15 matches of 20 rats at 5-pound weight, 1 match of 50 rats and 1 match of 100 rats in 34 minutes 40 seconds on Tuesday, March 30, 1847. Tiny beat Summertown bitch "Crack" of 8 pounds, 12 Rats each, September 14th. Beat the dog "Twig" at 6 1/2 pounds on November 7th. On Tuesday, March 28, 1848, he was matched to kill 300 rats in 3 hours. He accomplished the unprecedented test in 54 minutes 50 seconds, which took place in the presence of a crowded audience at the Blue Anchor, Bonhill Row, St. Lukes. May 2, killed 20 rats in 8 minutes; May 23 won a match of 50 rats against Mr. Batty's bitch "Fun," 8 pounds. August 15, won a match against "Jim," 50 rats; September 5 won a match of 12 rats, 2 minutes 30 seconds. November 4 won a match of 100 rats, 30 minutes 5 seconds; January 31, 1849, won a match of 100 rats, 20 minutes 5 seconds; March 27 killed 200 rats 59 minutes 58 seconds."

Jack

editJack was a Black and Tan Terrier owned by Kit Burns in New York City in the mid- to late 19th century.[17] Jack was a prized ratter, and Burns claimed that Jack killed 100 rats in 5 minutes and 40 seconds.[17] Burns had Jack taxidermied and mounted him, alongside other prized dogs, on the bar of his tavern called the Sportsmen's Hall, located at 273 Water Street.[17] Burns' first-floor amphitheatre could hold 100 spectators who were charged an admission of $1.50 to $5.00 depending on the dogs' quality, nearly a skilled labourer's daily wages. These shows were quite expensive as back in the day 1.00 was equal to 100 dollars today with that said these people were very wealthy and rich being able to buy a ticket to these shows. [18] The rat pit was about 8 ft square with 4-ft-high walls.[18] On the New York City waterfront rat baiting was quite lucrative with a purse of $125 not uncommon.[19] This created a high demand for rats with some rat catchers earning $0.05 to $0.12 per rat.[19]

Kit Burns' rat-pit activities are described by author James Dabney McCabe in his book Secrets of the Great City, published in 1868, at page 388,[20] as follows:

- "Rats are plentiful along the East River and Burns has no difficulty in procuring as many as he desires. These and his dogs furnish the entertainment in which he delights. The principal room of the house is arranged as an amphitheatre. The seats are rough wooden benches and in the centre is a ring or pit enclosed by a circular wooden fence several feet high. A number of rats are turned into this pit and a dog of the best ferret stock is thrown in amongst them. The little creature at once falls to work to kill the rats, bets being made that she will destroy, so many rats in a given time. The time is generally made by the little animal who is well known to and a great favorite with the yelling blasphemous wretches who line the benches. The performance is greeted with shouts oaths and other frantic demonstrations of delight. Some of the men will catch up the dog in their arms and press it to their bosom in a frenzy of joy or kiss it as if it were a human being unmindful or careless of the fact that all this while the animal is smeared with the blood of its victims. The scene is disgusting beyond description."

On 31 November 1870, Henry Bergh the founder of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals raided the Sportsman's Hall and arrested Burns under an anti-cruelty to animals law passed by the New York state legislature four years prior.[21] The Sportsman Hall stayed permanently closed after the raid.

Although little of the original structure remains, Sportsman's Hall occupied the land where the Joseph Rose House and Shop, a four-unit luxury apartment house, now lies and is the third oldest house in Manhattan after St. Paul's Chapel and the Morris-Jumel Mansion.[22][23]

Decline

editToward the latter half of Queen Victoria's reign, criticism of the practice mounted. The animal welfare movement opposed the practice much like they did other forms of animal baiting. More favourable ideas of rats as living animals rather than vermin arose, alongside a new interest in their positive role in the maintenance of an urban ecosystem.[24] (It was only after the decline of rat baiting that rats became associated with the spread of disease.[24]) Additionally, when ratting moved from being a countryside pastime to the betting arenas of inner London, it became associated with the base vices of lower-class citizens.[24] Baiting sports diminished in popularity and the dog exhibition shows brought by the gentry slowly replaced the attraction as a more enlightened form of animal entertainment.[25]

The last public competition in the United Kingdom took place in Leicester in 1912. The owner was prosecuted and fined, and had to give a promise to the court that he would never again promote such entertainment.[1]

Rat hunting in modern times

editRat hunting and rat-baiting are not the same activities. Rat hunting is the legal use of dogs, often referred to as ratters, for pest control of non-captured rats in an unconfined space, such as a barn or field.[26][27][28] In the United Kingdom the hunting of rats with dogs is legal under the Hunting Act 2004.[29] Due to rat infestations,[30] terriers are now being used for ratting to hunt and kill rats in major cities around the world, including the United Kingdom,[31] the United States[32][33][34][35][36] and Vietnam.[37] The use of ratting dogs is considered to be the most environmentally friendly, humane and efficient method of exterminating rats.[38][39] The article Rats in New York City provides some background about the problem with urban rats in the modern era.

In popular culture

edit- A rat-baiting scene is included in the 1979 film The First Great Train Robbery.[citation needed]

- In the movie Gangs of New York (2002), a scene involves rat baiting.[40][41]

- In the book Let Loose the Dogs (2003) by Maureen Jennings, as well as its TV adaptation, the main storyline is that a murder occurred following a rat-baiting contest.[citation needed]

- In Season 1, Episode 4 of The Knick (2014), there is a scene depicting rat baiting. A human, rather than a dog, is the one in the pit with the rats.[42][43]

Gallery

edit-

Die Gartenlaube, c.1858 (The Garden Arbour)

-

Rat-baiting c.1873

-

Combat de Chiens ratier et de rats a l'exposition canine. --- Champs-Élysées c.1865

-

The Great 100 Rat Match, c.1858

-

Rat fighting, recreation of King Louis XI of France, 1461-1483, c.1883

See also

edit- Earthdog trial

- Huddersfield Ben, ratting dog.

- Hatch, earliest scientifically confirmed ratting dog.

- Ryders Alley Trencher-fed Society (R.A.T.S.) is a New York City group that does ratting with dogs.

References

edit- ^ a b C & G's Crazy Critters Rattery. "Ratting History: A Night at the Rat Pit". Archived from the original on 23 March 2006. Retrieved 14 July 2006.

- ^ Turnspit Quakers Alley

- ^ a b c Phil Drabble (1948). "Staffords and baiting sports". In Brian Vesey-Fitzgerald (ed.). The book of the dog. Los Angeles: Borden Publishing.

- ^ Henry Mayhew (1851). "Jack Black". London Labor and the London Poor. Vol. 3. London: Griffen, Bohn and Company.

- ^ "Ratting Terriers". Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ "The Evolution of the English Toy Terrier (Black & Tan)". Archived from the original on 16 July 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ Stoutheart Staffordshire Bull Terriers – Staffords and Baiting Sports

- ^ a b c Fleig, D. (1996). History of Fighting Dogs. pp. 105–112 T.F.H. Publications. ISBN 0-7938-0498-1

- ^ a b c Homan, M. (2000). A Complete History of Fighting Dogs. pp. 121–131 Howell Book House Inc. ISBN 1-58245-128-1

- ^ Mayhew, H. (1851). London Labour and the London Poor, Volume 3, Chp 1, Jimmy Shaw. London: Griffen, Bohn and Company, Stationer's Hall Court.

- ^ Thorpe, Vanessa (31 March 2019). "Small wonder: tiny Victorian dog that killed 200 rats an hour". The Observer. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- ^ "Ratting Terriers". Amalek English Toy Terriers. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- ^ a b Museum of London

- ^ Peter Brown (27 November 2012). Toy Manchester Terrier: A Comprehensive Owner's Guide. CompanionHouse Books. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-62187-078-4.

- ^ Artillery Arms – homepage

- ^ Do You Know Who Jimmy Shaw was?

- ^ a b c "Kit Burns' Rat Pit". Infamous New York. WordPress. 22 October 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ a b Brynk, William (16 August 2005). "The Home of the Rat Pit". New York Sun. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ a b Madeja, Steve (1 June 2017). "Kit Burns' Rat Pit at 273 Water Street". Secrets of Manhattan. WordPress. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ McCabe, James Dabney (1868). Secrets of the Great City. Jones Brothers & Co. p. 388.

- ^ Lane, Marion S; Zawistowski, Stephen (2008). Heritage of Care: The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-275-99021-3.

- ^ Bunyan, Patrick. All Around the Town: Amazing Manhattan Facts and Curiosities. New York: Fordham University Press, 1999. (pg. 57) ISBN 0-8232-1941-0

- ^ Wolfe, Gerard R. New York, 15 Walking Tours: An Architectural Guide to the Metropolis. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional, 2003. (pg. 49) ISBN 0-07-141185-2

- ^ a b c Pemberton, Neil (1 December 2014). "The Rat-Catcher's Prank: Interspecies Cunningness and Scavenging in Henry Mayhew's London". Journal of Victorian Culture. 19 (4): 520–535. doi:10.1080/13555502.2014.967548. ISSN 1355-5502.

- ^ Olmert, Meg Daley (16 October 2018). "Genes unleashed: how the Victorians engineered our dogs". Nature. 562 (7727): 336–337. Bibcode:2018Natur.562..336O. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-07039-z.

- ^ Ratting with Terriers. Cornwall: Matthew Noall. 2016.

- ^ Ratting with terriers. Which terrier is top?

- ^ A Rat Hunter Takes Bushwick A vintage way to tackle a newly pressing problem

- ^ Hunting Act 2004 - Schedule 1, Section 2, Subsection 3 - Rats

- ^ Why Chicago is Losing the War on Rats

- ^ "Jess Ratting". 20 June 2009. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2015 – via YouTube.

- ^ WP: Washington is full of rats. These dogs are happy to help with that

- ^ [https://www.curbed.com/2023/04/rat-hunting-dogs-bushwick-nyc.html A Rat Hunter Takes Bushwick A vintage way to tackle a newly pressing problem.}

- ^ "In Manhattan Alleys, Dogs on Rat Hunts Find Bags of Fun". The New York Times. 22 November 2013.

- ^ "The Rat-Hunting Dogs of New York City". NBC New York. 10 October 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ "The Rat Hunters of New York – Roads & Kingdoms". Roads & Kingdoms. 23 October 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ "Vietnam". Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ "Rat Hunting Dogs: The History Of Rat Terriers and Ratcatchers". A Life of Dogs. 24 February 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ "Barn Hunt Association". www.barnhunt.com. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ Ward, Geoffrey C. (6 October 2002). "Gangs of New York". NY Times. The New York Times Company. p. 11. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ Video: Gangs of New York Rat Baiting Scene

- ^ Macfarlane, Steve (6 September 2014). "The Knick Recap: Season 1, Episode 4, "Where's the Dignity?"". Slant Magazine. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ "The Knick". Retrieved 21 June 2021 – via Twitter.

Bibliography

edit- Barnett, A. (2002). The Story of Rats: Their Impact on Us, and Our Impact on Them. Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW. ISBN 1-86508-519-7

- Fleig, D. (1996). History of Fighting Dogs. pp. 105–112 T.F.H. Publications. ISBN 0-7938-0498-1

- Hendrickson, R. (1984). More Cunning Than Man: A Social History of Rats and Man. Stein & Day Pub. ISBN 0-8128-2894-1

- Homan, M. (2000). A Complete History of Fighting Dogs. pp. 121–131 Howell Book House Inc. ISBN 1-58245-128-1

- Matthews, I. (1898). Full Revelations of a Professional Rat-Catcher. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-104-13023-7

- Mayhew, H. (1851). London Labour and the London Poor, Volume 3, Chp 1, Jimmy Shaw. London: Griffen, Bohn and Company, Stationer's Hall Court. London: Griffen, Bohn and Company, Stationer's Hall Court.

- Plummer, D. (1979). Tales of a Rat-hunting Man. ISBN 0-86072-025-X

- Rodwell, J. (1858). The Rat: Its History & Destructive Character. G. Routledge & Co. London. ISBN 978-1354531174

- Rodwell, J. (1850). The Rat! and Its Cruel Cost to the Nation. Palala Press. ISBN 978-1347118931

- Sullivan, R. (2004). Rats: A Year with New York's Most Unwanted Inhabitants. Granta Books, London. ISBN 978-0756966409

- Sullivan, R. (2005). Rats : Observations on the History and Habitat of the City's Most Unwanted Inhabitants. Chapter 9 Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 1-58234-385-3

- Zinsser, H. (1935). Rats, Lice and History. Blue Ribbon Books, Inc. ISBN 978-1412806725

External links

edit- Terriers at rat pits

- Turnspit Public House, Quakers Alley

- Terrier Man – Rat Dogs

- Scientific American, "Monkey, Dog, and Rats", 20 November 1880, p. 326 (report of a competition to kill twelve rats between a monkey and fox terrier)