The Red Hills salamander (Phaeognathus hubrichti) is a fairly large, terrestrial salamander growing to about 255 millimetres (10.0 in). Its body color is gray to brownish without markings, and its limbs are relatively short. It is the official state amphibian of Alabama,[5] the state it is endemic to.[1][4] It is the only species in the genus Phaeognathus.[6]

| Red Hills salamander | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Urodela |

| Family: | Plethodontidae |

| Subfamily: | Plethodontinae |

| Genus: | Phaeognathus Highton, 1961 |

| Species: | P. hubrichti

|

| Binomial name | |

| Phaeognathus hubrichti Highton, 1961[4]

| |

Habitat

editThe range of the Red Hills salamander is restricted to a narrow belt of two geological formations, approximately 60 miles (97 km) long (east to west) and between 10 and 25 miles (40 km) wide (north to south), in southern Alabama. These formations are included within the Red Hills physiographic province of the Coastal Plain. The range is limited on the east by the Conecuh River and on the west by the Alabama River (Jordan and Mount 1975). Currently, there are eight published locality records from Butler, Conecuh, Covington, Crenshaw, and Monroe Counties (Brandon 1965; Schwaner and Mount 1970).

This species inhabits burrows located on the slopes of moist, cool mesic ravines shaded by an overstory of predominately hardwood trees. These areas are underlain by a subsurface siltstone stratum containing many crevices, root tracings, and solution channels which are utilized by the Salamander. The topsoil in typical habitat is sandy loam.

Data for comparison of habitat changes are available from two studies; one by French (1976) and one by Dodd (1989). Ninety-one of the same sites were surveyed in both studies (each study also surveyed additional sites not visited by the other study). Of these 91 sites, 54 appeared similar to earlier descriptions, 19 had improved habitat conditions, and 18 were adversely affected by timber cutting since 1976. Of the 19 sites judged to have improved, 18 had been cleared of trees or had been selectively cut prior to French's survey but have since regrown a full tree canopy. (None of these improved sites had been mechanically prepared for replanting.) In addition to these 91 sites, 14 others examined in the latest survey were damaged by timber cutting; their status in 1976, however, was unknown.

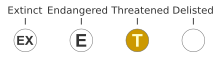

Conservation status

editP. hubrichti is considered a threatened species. Primary threats to this species include its restricted range, loss of habitat, a low reproductive rate, and a limited capability of dispersal. Of the approximately 63,000 acres (250 km2) of remaining habitat, about 60 percent is currently owned or leased by paper companies which primarily use a clear-cut system of forest management. This technique, coupled with mechanical site preparation for replanting, appears to completely destroy the habitat for the Red Hills salamander. However, as noted above, the Red Hills salamander prefers hardwood sites which are not managed using a clear-cut system. The clear-cut system is used primarily in pine management. Pine sites are not conducive as Red Hills salamander habitat. NatureServe considers the species Imperiled.[7]

In 2010, The Nature Conservancy acquired 1,786 acres (7.23 km2) of land in southwest Alabama in an effort to provide sufficient habitat to support the survival of the species. The land will eventually be transferred for recreational use to the state of Alabama.[8] Following acquisitions in 2020, the amount of protected habitat in the Red Hills physiographic province within Alabama reached over 11,000 acres (45 km2).[9]

Threats

editThe Red Hills salamander (Phaeognathus hubrichti), a unique and critically endangered amphibian species, faces a myriad of challenges that endanger its habitat and future existence. The species have suffered from overcollection as well.[10]

Habitat degradation

editThe Red Hills salamander confronts habitat reduction due to activities such as timber harvesting, conversion of mesic ravines into pine monocultures, and the clearing of ridge tops above ravines. These activities either destroy or degrade the available habitat. While overcollection was a concern in the past, it is no longer considered a significant threat. The majority of Red Hills salamander habitats are situated on privately owned timber company lands, where detrimental forestry practices persist, despite some improvements through management agreements. Additionally, feral pigs pose a threat in specific areas.[10]

Infectious disease

editAn emerging disease threat looms over the Red Hills salamander in the form of the salamander chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans, or "Bsal"). This pathogen has caused dramatic declines in European fire salamanders since its apparent arrival in 2008, possibly introduced through the international pet trade. While Bsal's presence has not been confirmed in the Americas, its rapid spread in Europe raises concerns about potential introduction. The impact on salamander populations in the US could be severe if Bsal is introduced, necessitating immediate mitigation measures to safeguard the Red Hills salamander's future.[10]

References

edit- This article is based on a (public domain) account in Endangered and Threatened Species of the Southeastern United States (The Red Book) FWS Region 4 -- As of 2/91 [1].

- ^ a b IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group (2022). "Phaeognathus hubrichti". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T16801A118974152. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "Red Hills salamander (Phaeognathus hubrichti)". Environmental Conservation Online System. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ 41 FR 53032

- ^ a b Frost, Darrel R. (2021). "Phaeognathus hubrichti Highton, 1961". Amphibian Species of the World: An Online Reference. Version 6.1. American Museum of Natural History. doi:10.5531/db.vz.0001. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ "Official Alabama State Amphibian". Alabama Emblems, Symbols and Honors. Alabama Department of Archives & History. 2003-11-06. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ^ Frost, Darrel R. (2021). "Phaeognathus Highton, 1961". Amphibian Species of the World: An Online Reference. Version 6.1. American Museum of Natural History. doi:10.5531/db.vz.0001. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ "NatureServe Explorer 2.0". explorer.natureserve.org. Retrieved 2023-04-17.

- ^ "Nature Conservancy Buys Key Red Hills Priority Forest Site, Protects Rare Species". The Nature Conservancy (Press release). 16 April 2010. Archived from the original on 5 October 2010.

- ^ Rainer, David (17 December 2020). "Monroe County Acquisition Protects Red Hills Salamander Habitat". Outdoor Alabama. Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ a b c "Redlist - Red Hills Salamander".

- Brandon, R. A. 1965. Morphological Variation and Ecology of the Salamander, Phaeognathus hubrichti. Copeia, 1965(1):67-71. doi:10.2307/1441241. JSTOR 1441241.

- Dodd, C.K., Jr. 1989. Status of the Red Hills Salamander is Reassessed. Endangered Species Technical Bulletin 14(1-2):10-11.

- French, T.W. 1976. Report on the Status and Future of the Red Hills Salamander, Phaeognathus hubrichti. Rep. to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Jackson, MS. 9pp + maps.

- Jordan, J. R., Jr., and R. H. Mount. 1975. The Status of the Red Hills Salamander, Phaeognathus hubrichti, Highton. Jour. Herpetol. 9(2):211-215.

- Schwaner, T. D., and R. H. Mount. 1970. Notes on the Distribution, Habits, and Ecology of the Salamander Phaeognathus hubrichti Highton. Copeia, 1970(3):571–573. doi:10.2307/1442289. JSTOR 1442289.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1983. Red Hills Salamander Recovery Plan. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Atlanta, Georgia. 23 pp.

External links

edit- Data related to Phaeognathus hubrichti at Wikispecies

- Media related to Phaeognathus hubrichti at Wikimedia Commons