Sibutramine, formerly sold under the brand name Meridia among others, is an appetite suppressant which has been discontinued in many countries. It works as a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) similar to certain antidepressants. Until 2010, it was widely marketed and prescribed as an adjunct in the treatment of obesity along with diet and exercise. It has been associated with increased cardiovascular diseases and strokes and has been withdrawn from the market in 2010 in several countries and regions including Australia,[2] Canada,[3] China,[4] the European Union,[5] Hong Kong,[6] India,[7] Mexico, New Zealand,[8] the Philippines,[9] Thailand,[10] the United Kingdom,[11] and the United States.[12] However, the drug remains available in some countries.[13]

| |

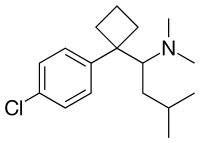

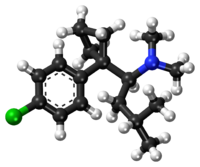

Sibutramine (top), (S)-(−)-sibutramine (bottom) | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Meridia, others |

| Other names | BTS-54524 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a601110 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; Anoretic |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Absorption 77%, considerable first-pass metabolism |

| Protein binding | 97%, (94% for its desmethyl metabolites, M1 & M2) |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (CYP3A4-mediated) |

| Elimination half-life | 1 hour (sibutramine), 14 hours (M1) & 16 hours (M2) |

| Excretion | Urine (77%), feces (8%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.130.097 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H26ClN |

| Molar mass | 279.85 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Sibutramine was originally developed in 1988 by Boots in Nottingham, UK,[14] and manufactured and marketed by Abbott Laboratories and sold under a variety of brand names including Reductil, Meridia, Siredia, and Sibutrex before its withdrawal 2010 from most markets. It was classified as a Schedule IV controlled substance in the United States.

As of 2018, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) still found sibutramine in over 700 diet supplements marketed as "natural", "traditional", or "herbal remedies".

Medical uses

editSibutramine has been used to produce appetite suppression for the purpose of attaining weight loss in the treatment of patients with obesity.

Contraindications

editSibutramine is contraindicated in patients with:

- Psychiatric conditions as bulimia nervosa, anorexia nervosa, severe depression, or pre-existing mania

- Patients with a history of or a predisposition to drug or alcohol abuse

- Hypersensitivity to the drug or any of the inactive ingredients

- Patients below 18 and above 65 years of age[15]

- Concomitant treatment with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI), antidepressant, or other centrally active drugs, particularly other anoretics

- History of peripheral artery disease

- Hypertension that is not sufficiently controlled (e.g., >145/90 mmHg), caution in controlled hypertension

- Existing pulmonary hypertension

- Existing damage on heart valves, congestive heart failure, previous myocardial infarction (heart attack), tachycardia, arrhythmia, or cerebrovascular disease (e.g., stroke or transient ischemic attack [TIA])[15]

- Hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid gland)

- Closed-angle glaucoma

- Epilepsy

- Enlargement of the prostate gland with urinary retention (relative contraindication)

- Pheochromocytoma

- Pregnant and lactating women (relative contraindication)

Side effects

editA higher number of cardiovascular events has been observed in people taking sibutramine versus control (11.4% vs. 10.0%).[16] In 2010, the FDA noted the concerns that sibutramine increases the risk of heart attacks and strokes in patients with a history of cardiovascular disease.[16]

Frequently encountered side effects include dry mouth, paradoxically increased appetite, nausea, strange taste in the mouth, abdominal pain, constipation, insomnia, dizziness, drowsiness, menstrual cramps, headache, flushing, or joint/muscle pain.

In a 2016 Cochrane review, sibutramine was found to substantially increase blood pressure and heart rate in some patients, in the updated review in 2021 sibutramine was not included since the drug had been withdrawn from the market.[17] When used, regular blood pressure monitoring needed to be performed.

The following side effects are infrequent but serious and require immediate medical attention: cardiac arrhythmias, paresthesia, mental changes (e.g., excitement, restlessness, confusion, depression, rare thoughts of suicide).

Symptoms that require urgent medical attention are seizures, problems urinating, abnormal bruising or bleeding, melena, hematemesis, jaundice, fever and rigors, chest pain, hemiplegia, abnormal vision, dyspnea and edema.

Currently, no case of pulmonary hypertension has been noted. (Fenfluramine, of the 1990s "Fen-Phen" combo, forced excess release of neurotransmitters—a different action. Phentermine was uninvolved in the rare—but clinically significant—heart issues of fenfluramine.)

Interactions

editSibutramine has a number of clinically significant interactions. The concomitant use of sibutramine and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs, such as selegiline) is not indicated, as it may increase the risk of serotonin syndrome, a somewhat rare but serious adverse drug reaction.[18] Sibutramine should not be taken within two weeks of stopping or starting an MAOI. Taking both sibutramine and certain medications used in the treatment of migraines—such as ergolines and triptans—as well as opioids, may also increase the risk for serotonin syndrome, as may the use of more than one serotonin reuptake inhibitor at the same time.[18]

The concomitant use of sibutramine and drugs which inhibit CYP3A4, such as ketoconazole and erythromycin, may increase plasma levels of sibutramine.[19] Sibutramine does not affect the efficacy of hormonal contraception.[18]

Pharmacology

editPharmacodynamics

edit| Compound | SERT | NET | DAT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sibutramine | 298–2,800 | 350–5,451 | 943–1,200 |

| Desmethylsibutramine | 15 | 20 | 49 |

| (R)-Desmethylsibutramine | 44 | 4 | 12 |

| (S)-Desmethylsibutramine | 9,200 | 870 | 180 |

| Didesmethylsibutramine | 20 | 15 | 45 |

| (R)-Didesmethylsibutramine | 140 | 13 | 8.9 |

| (S)-Didesmethylsibutramine | 4,300 | 62 | 12 |

| Values are Ki (nM). | |||

Sibutramine is a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) that, in humans, reduces the reuptake of norepinephrine (by ~73%), serotonin (by ~54%), and dopamine (by ~16%),[22] thereby increasing the levels of these substances in synaptic clefts and helping enhance satiety; the serotonergic action, in particular, is thought to influence appetite. Older anorectic agents such as amphetamine and fenfluramine force the release of these neurotransmitters rather than affecting their reuptake.[23]

Sibutramine's mechanism of action is similar to tricyclic antidepressants, and it has demonstrated antidepressant effects in animal models of depression.[14] It was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in November 1997[24] for the treatment of obesity.

Sibutramine is reported to be a prodrug to two active metabolites, desmethylsibutramine (M1; BTS-54354) and didesmethylsibutramine (M2; BTS-54505), with much greater potency as monoamine reuptake inhibitors.[25][26] Further studies have indicated that the (R)-enantiomers of each metabolite exert significantly stronger anorectic effects than the (S)-enantiomers.[27]

Unlike other serotonergic appetite suppressants like fenfluramine, sibutramine and its metabolites have only low and likely inconsequential affinity for the 5-HT2B receptor.[22]

Pharmacokinetics

editSibutramine is well absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract (77%), but undergoes considerable first-pass metabolism, reducing its bioavailability. The drug itself reaches its peak plasma level after 1 hour and has also a half-life of 1 hour. Sibutramine is metabolized by cytochrome P450 isozyme CYP3A4 into two pharmacologically active primary and secondary amines (called active metabolites 1 and 2) with half-lives of 14 and 16 hours, respectively. Peak plasma concentrations of active metabolites 1 and 2 are reached after three to four hours. The following metabolic pathway mainly results in two inactive conjugated and hydroxylated metabolites (called metabolites 5 and 6). Metabolites 5 and 6 are mainly excreted in the urine.

Chemistry

editSibutramine has usually been used in the form of the hydrochloride monohydrate salt.

Detection in body fluids

editSibutramine and its two active N-demethylated metabolites may be measured in biofluids by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Plasma levels of these three species are usually in the 1–10 μg/L range in persons undergoing therapy with the drug. The parent compound and norsibutramine are often not detectable in urine, but dinorsibutramine is generally present at concentrations of >200 μg/L.[28][29][30]

Society and culture

editRegulatory approval, 1997–2010

editSibutramine was originally developed in 1988 by Boots in Nottingham, UK,[14]/ and marketed by Knoll Pharmaceuticals after BASF/Knoll AG purchased the Boots Research Division in 1995. It was classified as a Schedule IV controlled substance in the United States.

In 1997, the US FDA approved it for weight loss and maintenance of weight loss in people with a BMI greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2 or for people with a BMI ≥27 kg/m2 who have other cardiovascular risk factors. It was manufactured and marketed by Abbott Laboratoriess.[31] It was sold under a variety of brand names including Reductil, Meridia, Siredia, and Sibutrex.

In 2002, studies looked into reports of sudden death, heart failure, renal failure and gastrointestinal problems. Despite a 2002 petition by Ralph Nader-founded NGO Public Citizen,[32] the FDA made no attempts to withdraw the drug, but was part of a Senate hearing in 2005.[33] Similarly, in 2004, David Graham, FDA "whistleblower", testified before a Senate Finance Committee hearing that sibutramine may be more dangerous than the conditions it is used for.[34]

Between January 2003 and November 2005, a large randomized-controlled "Sibutramine Cardiovascular OUTcomes" (SCOUT) study with 10,742 patients examined whether or not sibutramine administered within a weight management program reduces the risk for cardiovascular complications in people at high risk for heart disease and concluded that use of silbutramine had a RR 1.16 for the primary outcome (composit of nonfatal MI, nonfatal CVA, cardiac arrest, and CV death).[35]

In April 2010 David Haslam (chairman of the National Obesity Forum) said in a dissenting article, "Sibutramine: gone, but not forgotten", that the SCOUT study was flawed as it only covered high-risk patients and did not consider obese patients who did not have cardiovascular complications or similar contraindications.[36]

On January 21, 2010, the European Medicines Agency recommended suspension of marketing authorizations for sibutramine based on the SCOUT study results.[37]

In August 2010 the FDA added a new contraindication for patients over 65 years of age because clinical studies of sibutramine did not include sufficient numbers of such patients.[15]

On October 8, 2010, the FDA recommended against continued prescribing because of unnecessary cardiovascular risks to patients, asking Abbott Laboratories to voluntarily withdraw.[31] Abbott announced the same day that it was withdrawing sibutramine from the US market, citing concerns over minimal efficacy coupled with increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events.[38]

Counterfeit weight-loss products, 2008–present

editOn December 22, 2008, the United States Food and Drug Administration issued an alert to consumers naming 27 different products marketed as “dietary supplements” for weight loss, that illegally contain undisclosed amounts of sibutramine.[39][40] In March 2009, Dieter Müller et al. published a study of sibutramine poisoning cases from similar Chinese "herbal supplements" sold in Europe, containing as much as twice the dosage of the legally licensed drug.[41]

An additional 34 products were recalled by the FDA on April 22, 2009, further underscoring the risks associated with unregulated "herbal supplements" to unsuspecting persons. This concern is especially relevant to those with underlying medical conditions incompatible with undeclared pharmaceutical adulterants.[42] In January 2010, a similar alert was issued for counterfeit versions of the over-the-counter weight loss drug Alli sold over the Internet. Instead of the active ingredient orlistat, the counterfeit drugs contain sibutramine, and at concentrations at least twice the amount recommended for weight loss.[43]

In March 2010 Health Canada advised the public that illegal "Herbal Diet Natural" had been found on the market, containing sibutramine, which is a prescription drug in Canada, without listing sibutramine as an ingredient.[44] In October 2010 FDA notified consumers that "Slimming Beauty Bitter Orange Slimming Capsules contain the active pharmaceutical ingredient sibutramine, a prescription-only drug which is a stimulant. Sibutramine is not listed on the product label."[45]

In October 2010 the MHRA in the UK issued a warning regarding "Payouji tea" and "Pai You Guo Slim Capsules" which were found to contain undeclared quantities of sibutramine.[46]

On December 30, 2010, the FDA released a warning regarding "Fruta Planta" dietary products, which were found to contain undeclared amounts of sibutramine. The recall stated that "there is NO SAFE formula on the US market and that all versions of Fruta Planta contain sibutramine. All versions of the formula are UNSAFE and should not be purchased from any source."[47]

In 2011, some illegal weight loss products imported into Ireland have been found to contain sibutramine.[48][49] In 2012, similar concerns were raised in Australia, where illegal imported supplements have been found to contain sibutramine, resulting in public alerts from Australia's Therapeutic Goods Administration.[50]

In October 2011, the FDA warned that 20 brands of dietary supplements were tainted with sibutramine.[51]

In a 2018 study the FDA found synthetic additives including sibutramine in over 700 diet supplements marketed as "natural", "traditional" or "herbal remedies".[52]

References

edit- ^ Anvisa (2023-03-31). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-04-04). Archived from the original on 2023-08-03. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- ^ "Sibutramine (Reductil) - withdrawal in Australia". Therapeutic Goods Administration (Tga). Therapeutic Goods Administration, Department of Health, Australian Government. 2010. Archived from the original on 2014-07-03. Retrieved 2014-10-06.

- ^ Health Canada Endorsed Important Safety Information on MERIDIA (Sibutramine Hydrochloride Monohydrate) Archived 2013-01-11 at the Wayback Machine: Subject: Voluntary withdrawal of Meridia (sibutramine) capsules from the Canadian market.

- ^ "Notification of Termination of Production, Sale, and Usage of Sibutramine Preparations and Their Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient". sda.gov in People's Republic of China. October 30, 2010. Archived from the original on 2011-10-07. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- ^ (in German) Sibutramin-Vertrieb in der Europäischen Union ausgesetzt [1] Archived 2012-07-19 at archive.today. Abbott Laboratories in Germany. Press Release 2010-01-21. Retrieved 2010-01-27

- ^ "De-registration of pharmaceutical products containing sibutramine" (Press release). info.gov in Hong Kong. November 2, 2010. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- ^ "Banned Medicines" (Press release). Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. February 10, 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

- ^ "Withdrawal of Sibutramine (Reductil) in New Zealand" (Press release). MedSafe in New Zealand. October 11, 2010. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- ^ "FDA warns online sellers of banned slimming pills". January 12, 2014. Archived from the original on January 15, 2014. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ^ "Thai FDA reveals voluntary withdrawal of sibutramine from the Thai market" (PDF) (Press release). Food and Drug Administration of Thailand. October 20, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-11. Retrieved 2010-12-22.

- ^ "Top obesity drug sibutramine being suspended". BBC News. 2010-01-22. Archived from the original on 2010-01-25. Retrieved 2010-01-22.

- ^ Rockoff JD, Dooren JC (October 8, 2010). "Abbott Pulls Diet Drug Meridia Off US Shelves". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 11 October 2010. Retrieved 8 October 2010.

- ^ "Sibutramine - Drugs.com". drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2017-10-08. Retrieved 2017-10-08.

- ^ a b c Buckett WR, Thomas PC, Luscombe GP (1988). "The pharmacology of sibutramine hydrochloride (BTS 54 524), a new antidepressant which induces rapid noradrenergic down-regulation". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 12 (5): 575–584. doi:10.1016/0278-5846(88)90003-6. PMID 2851857. S2CID 24787523.

- ^ a b c "The FDA August 2010 drug safety update". fda.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-01-12. Retrieved 2019-12-16.

- ^ a b "Meridia (sibutramine hydrochloride): Follow-Up to an Early Communication about an Ongoing Safety Review". United States Food and Drug Administration. 1 February 2010. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012.

- ^ Siebenhofer A, Winterholer S, Jeitler K, Horvath K, Berghold A, Krenn C, Semlitsch T (January 2021). "Long-term effects of weight-reducing drugs in people with hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD007654. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007654.pub5. PMC 8094237. PMID 33454957.

- ^ a b c "Meridia Side Effects, and Drug Interactions". RxList.com. 2007. Archived from the original on 2008-08-09. Retrieved 2007-04-29.

- ^ (in Portuguese) Cloridrato de sibutramina monoidratado. Bula. [Sibutramine hydrochloride monohydrate—label information]. Medley (2007).

- ^ Nisoli E, Carruba MO (October 2000). "An assessment of the safety and efficacy of sibutramine, an anti-obesity drug with a novel mechanism of action". Obesity Reviews. 1 (2): 127–139. doi:10.1046/j.1467-789x.2000.00020.x. PMID 12119986. S2CID 20553857.

- ^ Rothman RB, Baumann MH (May 2009). "Serotonergic drugs and valvular heart disease". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 8 (3): 317–329. doi:10.1517/14740330902931524. PMC 2695569. PMID 19505264.

- ^ a b "Meridia (sibutramine hydrochloride monohydrate) Capsules CIV. Full Prescribing Information" (PDF). Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL 60064, U.S.A. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ Heal DJ, Aspley S, Prow MR, Jackson HC, Martin KF, Cheetham SC (August 1998). "Sibutramine: a novel anti-obesity drug. A review of the pharmacological evidence to differentiate it from d-amphetamine and d-fenfluramine". International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 22 (Suppl 1): S18-28, discussion S29. PMID 9758240.

- ^ "FDA APPROVES SIBUTRAMINE TO TREAT OBESITY" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. November 24, 1997. Retrieved 2007-04-29.

- ^ Kim KA, Song WK, Park JY (November 2009). "Association of CYP2B6, CYP3A5, and CYP2C19 genetic polymorphisms with sibutramine pharmacokinetics in healthy Korean subjects". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 86 (5): 511–518. doi:10.1038/clpt.2009.145. PMID 19693007. S2CID 24789264.

- ^ Hofbauer K (2004). Pharmacotherapy of obesity : options and alternatives. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-415-30321-7.

- ^ Glick SD, Haskew RE, Maisonneuve IM, Carlson JN, Jerussi TP (May 2000). "Enantioselective behavioral effects of sibutramine metabolites". European Journal of Pharmacology. 397 (1): 93–102. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00216-8. PMID 10844103.

- ^ Jain DS, Subbaiah G, Sanyal M, Shrivastav PS, Pal U, Ghataliya S, et al. (2006). "Liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry validated method for the simultaneous quantification of sibutramine and its primary and secondary amine metabolites in human plasma and its application to a bioequivalence study". Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 20 (23): 3509–3521. Bibcode:2006RCMS...20.3509J. doi:10.1002/rcm.2760. PMID 17072906.

- ^ Thevis M, Sigmund G, Schiffer AK, Schänzer W (2006). "Determination of N-desmethyl- and N-bisdesmethyl metabolites of Sibutramine in doping control analysis using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry". European Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 12 (2). Chichester, England: 129–36. doi:10.1255/ejms.797. PMID 16723754. S2CID 23359461.

- ^ Baselt R (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 1426–1427.

- ^ a b Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (2019-06-28). "FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA Recommends Against the Continued Use of Meridia (sibutramine)". FDA. Archived from the original on 2022-12-12. Retrieved 2022-12-12.

- ^ Wolfe SM, Sasich LD, Barbehenn E (March 19, 2002). "Petition to FDA to ban the diet drug sibutramine (MERIDIA) (HRG Publication #1613)". Public Citizen. Archived from the original on 2006-12-19. Retrieved 2007-04-29.

- ^ Japsen B (13 March 2005). "FDA weighs decision on Meridia; Health advisory likely for Abbott obesity drug". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois. p. 1.

- ^ Hearing of 17 November 2004. "Insider: FDA Won't Protect Public". CBS News. 19 November 2004. Archived from the original on 19 May 2006.

- ^ James WP, Caterson ID, Coutinho W, Finer N, Van Gaal LF, Maggioni AP, et al. (September 2010). "Effect of sibutramine on cardiovascular outcomes in overweight and obese subjects" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 363 (10): 905–917. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1003114. hdl:2437/111825. PMID 20818901.

- ^ Haslam D (April 2010). "Sibutramine: gone, but not forgotten" (PDF). Pract Diab Int. 27 (3): 96–97. doi:10.1002/pdi.1453. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2015.

- ^ "European Medicines Agency recommends suspension of marketing authorisations for sibutramine" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. January 21, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-04-01.

- ^ Andrew Pollack (October 8, 2010). "Abbott Labs Withdraws Meridia From Market". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 28, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- ^ "FDA warns consumers about tainted weight loss pills" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 22 December 2008.

- ^ "Consumer directed questions and answers about FDA's initiative against contaminated weight loss products". U.S. Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. 22 December 2008. Archived from the original on 17 March 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ Müller D, Weinmann W, Hermanns-Clausen M (March 2009). "Chinese slimming capsules containing sibutramine sold over the Internet: a case series". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 106 (13): 218–222. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2009.0218. PMC 2680571. PMID 19471631.

- ^ 34 weight loss products recalled Archived 2009-04-26 at the Wayback Machine, WebMD, 22 April 2009.

- ^ "Fake Alli diet pills can pose health risks". CNN.com. January 23, 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-01-25. Retrieved 2010-01-24.

- ^ "Herbal diet product poses heart risk". CBC News. March 26, 2010. Archived from the original on March 28, 2010. Retrieved March 26, 2010.

- ^ "FDA Alert: Slimming Beauty Bitter Orange Slimming Capsules: Undeclared Drug Ingredient". drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2018-08-25. Retrieved 2018-01-23.

- ^ "Press release: Warning over unlicensed herbal Payouji tea and Pai You Guo Slim Capsules". United Kingdom Medicines & Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. 20 October 2010. Archived from the original on 9 February 2012.

- ^ "PRock Marketing, LLC Issues a Voluntary Nationwide Recall of All weight loss formulas and variation of formulas of Reduce Weight Fruta Planta/Reduce Weight Dietary Supplement". United States Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012.

- ^ Pope C. "Seizures of illegal medicines rise". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 2012-10-24. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- ^ "FDA Alert: Slim Xtreme Herbal Slimming Capsule: Undeclared Drug Ingredient". drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2018-08-25. Retrieved 2018-01-23.

- ^ "Majestic slimming capsules: Safety advisory". Therapeutic Goods Administration. Australian Government. 9 November 2012. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ Carroll L (19 October 2011). "'Natural' diet pills tainted with banned prescription drug". MSNBC. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012.

- ^ Cohen R (12 October 2018). "No Wonder It Works So Well: There May Be Viagra In That Herbal Supplement". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 2018-10-13. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

External links

edit- Abbott Press Release on Meridia Withdrawal Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Sibutramine drug information from Merck Manual. Includes dosage information and a comprehensive list of international brand names

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) product safety website