The Rogue River (Tolowa: yan-shuu-chit’ taa-ghii~-li~’,[8] Takelma: tak-elam[9]) in southwestern Oregon in the United States flows about 215 miles (346 km) in a generally westward direction from the Cascade Range to the Pacific Ocean. Known for its salmon runs, whitewater rafting, and rugged scenery, it was one of the original eight rivers named in the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968. Beginning near Crater Lake, which occupies the caldera left by the explosive volcanic eruption and collapse of Mount Mazama, the river flows through the geologically young High Cascades and the older Western Cascades, another volcanic province. Further west, the river passes through multiple exotic terranes of the more ancient Klamath Mountains. In the Kalmiopsis Wilderness section of the Rogue basin are some of the world's best examples of rocks that form the Earth's mantle. Near the mouth of the river, the only dinosaur fragments ever discovered in Oregon were found in the Otter Point Formation, along the coast of Curry County.

| Rogue River | |

|---|---|

Rogue River from Hellgate Canyon | |

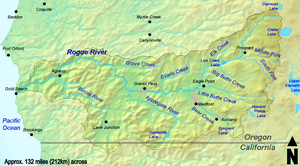

Map of the Rogue River watershed | |

| Etymology | Coquins (rogues), used by early French visitors to the region to describe the local Native Americans (Indians)[2] |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Oregon |

| County | Klamath, Douglas, Jackson, Josephine, and Curry |

| City | Grants Pass |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Boundary Springs in Crater Lake National Park |

| • location | Cascade Range, Klamath County, Oregon |

| • coordinates | 43°3′57″N 122°13′56″W / 43.06583°N 122.23222°W[1] |

| • elevation | 5,320 ft (1,620 m)[3] |

| Mouth | Pacific Ocean |

• location | Gold Beach, Curry County, Oregon |

• coordinates | 42°25′21″N 124°25′45″W / 42.42250°N 124.42917°W[1] |

• elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Length | 215 mi (346 km)[4] |

| Basin size | 5,156 sq mi (13,350 km2)[5] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | near Agness, 29.7 miles (47.8 km) from the mouth[6] |

| • average | 6,622 cu ft/s (187.5 m3/s)[6] |

| • minimum | 608 cu ft/s (17.2 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 290,000 cu ft/s (8,200 m3/s) |

| Type | Wild 131.1 miles (211.0 km) Scenic 67.4 miles (108.5 km) Recreational 45.3 miles (72.9 km) |

| Designated | October 2, 1968[7] |

People have lived along the Rogue River and its tributaries for at least 8,500 years. European explorers made first contact with Native Americans (Indians) toward the end of the 18th century and began beaver trapping and other activities in the region. Clashes, sometimes deadly, occurred between the natives and the trappers and later between the natives and European-American miners and settlers. These struggles culminated with the Rogue River Wars of 1855–56 and removal of most of the natives to reservations outside the basin. After the war, settlers expanded into remote areas of the watershed and established small farms along the river between Grave Creek and the mouth of the Illinois River. They were relatively isolated from the outside world until 1895, when the Post Office Department added mail boat service along the lower Rogue. As of 2010, the Rogue has one of the two remaining rural mail-boat routes in the United States.

Dam building and removal along the Rogue has generated controversy for more than a century; an early fish-blocking dam (Ament) was dynamited by vigilantes, mostly disgruntled salmon fishermen. By 2010, all of the main-stem dams downstream of a huge flood-control structure 157 miles (253 km) from the river mouth had been removed. Aside from dams, threats to salmon include high water temperatures. Although sometimes too warm for salmonids, the main stem Rogue is relatively clean, ranking between 85 and 97 (on a scale of 0 to 100) on the Oregon Water Quality Index (OWQI).

Although the Rogue Valley near Medford is partly urban, the average population density of the Rogue watershed is only about 32 people per square mile (12 per km2). Several historic bridges cross the river near the more populated areas. Many public parks, hiking trails, and campgrounds are near the river, which flows largely through forests, including national forests. Biodiversity in many parts of the basin is high; the Klamath-Siskiyou temperate coniferous forests, which extend into the southwestern Rogue basin, are among the four most diverse of this kind in the world.

Course

editThe Rogue River begins at Boundary Springs on the border between Klamath and Douglas counties near the northern edge of Crater Lake National Park. Although it changes direction many times, it flows generally west for 215 miles (346 km) from the Cascade Range through the Rogue River – Siskiyou National Forest and the Klamath Mountains to the Pacific Ocean at Gold Beach. Communities along its course include Union Creek, Prospect, Trail, Shady Cove, Gold Hill and Rogue River, all in Jackson County; Grants Pass and Galice in Josephine County; and Agness, Wedderburn and Gold Beach in Curry County. Significant tributaries include the South Fork Rogue River, Elk Creek, Larson Creek, Bear Creek, the Applegate River, and the Illinois River.[10] Arising at 5,320 feet (1,622 m) above sea level, the river loses more than 1 mile (1.6 km) in elevation by the time it reaches the Pacific.[3][1] It was one of the original eight rivers named in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968, which included 84 miles (135 km) of the Rogue, from 7 miles (11.3 km) west of Grants Pass to 11 miles (18 km) east of the mouth at Gold Beach.[11] In 1988, an additional 40 miles (64 km) of the Rogue between Crater Lake National Park and the unincorporated community of Prospect was named Wild and Scenic.[12] Of the river's total length, 124 miles (200 km), about 58 percent is Wild and Scenic.[11][12] The Rogue is one of only three rivers that start in or east of the Cascade Range in Oregon and reach the Pacific Ocean.[13] The others are the Umpqua River and Klamath River. These three Southern Oregon rivers drain mountains south of the Willamette Valley; the Willamette River and its tributaries drain north along the Willamette Valley into the Columbia River,[13] which starts in British Columbia rather than Oregon.

Discharge

editThe United States Geological Survey (USGS) operates five stream gauges along the Rogue River. They are located, from uppermost to lowermost, near Prospect,[14] Eagle Point,[15] Central Point,[16] Grants Pass,[17] and Agness. Between 1960 and 2007, the average discharge recorded by the Agness gauge at river mile (RM) 29.7 or river kilometer (RK) 47.8 was 6,622 cubic feet per second (188 m3/s). The maximum discharge during this period was 290,000 cubic feet per second (8,200 m3/s) on December 23, 1964, and the minimum discharge was 608 cubic feet per second (17 m3/s) on July 9 and 10, 1968. This was from a drainage basin of 3,939 square miles (10,202 km2), or about 76 percent of the entire Rogue watershed.[6] The maximum flow occurred between December 1964 and January 1965 during the Christmas flood of 1964, which was rated by the National Weather Service as one of Oregon's top 10 weather events of the 20th century.[18]

Watershed

editDraining 5,156 square miles (13,350 km2), the Rogue River watershed covers parts of Jackson, Josephine, Curry, Douglas, and Klamath counties in southwestern Oregon and Siskiyou and Del Norte counties in northern California.[5] The steep, rugged basin, stretching from the western flank of the Cascade Range to the northeastern flank of the Siskiyou Mountains, varies in elevation from 9,485 feet (2,891 m) at the summit of Mount McLoughlin in the Cascades to 0 feet (0 m), where the basin meets the ocean.[19] The basin borders the watersheds of the Williamson River, Upper Klamath Lake, and the upper Klamath River on the east; the lower Klamath, Smith, and Chetco rivers on the south; the North Umpqua, South Umpqua, Coquille, and Sixes rivers on the north, and the Pacific Ocean on the west.[20]

In 2000, Jackson County had a population of about 181,300, most of them living in the Rogue River Valley cities of Ashland (19,500), Talent (5,600), Phoenix (4,100), Medford (63,200), Central Point (12,500), and Jacksonville (2,200).[21] Others in Jackson County lived in the cities of Shady Cove (2,300), Eagle Point (4,800), Butte Falls (400) and Rogue River (1,800). Josephine County had a population of 75,700, including the cities of Grants Pass (23,000) and Cave Junction (1,400).[21] Gold Beach (1,900) is the only city in Curry County (21,100) in the Rogue River basin. Only small, sparsely inhabited parts of the watershed are in Klamath and Douglas counties in Oregon[21] and Siskiyou and Del Norte counties in California.[22] The watershed's average population density is about 32 people per square mile (12.4/km2).[23]

Many overlapping entities including city, county, state, and federal governments share jurisdiction for parts of the watershed. About 60 percent of the basin is publicly owned and is managed by the United States Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), and the United States Bureau of Reclamation. Under provisions of the federal Clean Water Act, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), assisted by the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) and other agencies in both states, is charged with controlling water pollution in the basin.[19] United States National Forests and other forests cover about 83 percent of the basin; another 6 percent is grassland, 3 percent shrub, and only 0.2 percent wetland.[24] Urban areas account for slightly less than 1 percent and farms for about 6 percent.[24]

Precipitation in the Rogue basin varies greatly from place to place and season to season. At Gold Beach on the Pacific Coast it averages about 80 inches (2,000 mm) a year, whereas at Ashland, which is inland, it averages about 20 inches (510 mm).[24] The average annual precipitation for the entire basin is about 38 inches (970 mm).[24] Most of this falls in winter and spring, and summers are dry.[24] At high elevations in the Cascades, much of the precipitation arrives as snow and infiltrates permeable volcanic soils; snowmelt contributes to stream flows in the upper basin during the dry months.[21] Along the Illinois River in the lower basin, most of the precipitation falls as rain on shallow soils; rapid runoff leads to high flows during winter storms and low flows during the dry summer.[21] Average monthly temperatures for the whole basin range from about 68 °F (20 °C) in July and August to about 40 °F (4 °C) in December.[24] Within the basin, local temperatures vary with elevation.[24]

Geology

editHigh and Western Cascades

editArising near Crater Lake, the Rogue River flows from the geologically young High Cascades through the somewhat older Western Cascades and then through the more ancient Klamath Mountains.[24] The High Cascades are composed of volcanic rock produced at intervals from about 7.6 million years ago through geologically recent events such as the catastrophic eruption of Mount Mazama in about 5700 BCE. The volcano hurled 12 to 15 cubic miles (50 to 63 km3) of ash into the air, covering much of the western U.S. and Canada with airfall deposits. The volcano's subsequent collapse formed the caldera of Crater Lake.[25]

Older and more deeply eroded, the Western Cascades are a range of volcanoes lying west of and merging with the High Cascades. They consist of partly altered volcanic rock from vents in both volcanic provinces, including varied lavas and ash tuffs ranging in age from 0 to 40 million years.[26] As the Cascades rose, the Rogue maintained its flow to the ocean by down-cutting, which created steep narrow gorges and rapids in many places. Bear Creek, a Rogue tributary that flows south to north, marks the boundary between the Western Cascades to the east and the Klamath Mountains to the west.[24]

Klamath Mountains

editMuch more ancient than the upstream mountains are the exotic terranes of the Klamath Mountains to the west. Not until plate tectonics separated North America from Europe and North Africa and pushed it westward did the continent acquire, bit by bit, what became the Pacific Northwest, including Oregon. The Klamath Mountains consist of multiple terranes—former volcanic islands and coral reefs and bits of subduction zones, mantle, and seafloor—that merged offshore over vast stretches of time before colliding with North America as a single block about 150 to 130 million years ago. Much of the Rogue River watershed, including the Rogue River canyon, the Kalmiopsis Wilderness, the Illinois River basin, and Mount Ashland, are composed of exotic terranes.[27]

Among the oldest rocks in Oregon, some of the formations in these terranes date to the Triassic, nearly 250 million years ago.[28] Between 165 and 170 million years ago, in the Jurassic, faulting consolidated the Klamath terranes offshore during what geologists call the Siskiyou orogeny. This three- to five-million-year episode of intense tectonic activity pushed sedimentary rocks deep enough into the mantle to melt them and then forced them to the surface as granitic plutons. Belts of plutons, which contain gold and other precious metals, run through the Klamaths and include the Ashland pluton, the Grayback batholith east of Oregon Caves National Monument, the Grants Pass pluton, the Gold Hill pluton, the Jacksonville pluton, and others.[27] Miners have worked rich deposits of gold, silver, copper, nickel, and other metals in several districts of the Klamaths. Placer mining in the mid-19th century soon led to lode mining for gold. Aside from a mine in eastern Oregon, the Greenback Mine along Grave Creek, a Rogue tributary, was the most productive gold mine in Oregon.[28]

In Curry County, the lower Rogue passes through the Galice Formation, metamorphosed shale, and other rocks formed when a small oceanic basin in the merging Klamath terranes was thrust over other Klamath rocks about 155 million years ago. The lowest part of the seafloor of the Josephine Basin, as this ancient sea came to be called, rests on top of the Kalmiopsis Wilderness, where it is known as the Josephine ophiolite. Some of its rocks are peridotite, reddish-brown when exposed to oxygen but very dark green inside. According to geologist Ellen Morris Bishop, "These odd tawny peridotites in the Kalmiopsis Wilderness are among the world’s best examples of rocks that form the mantle."[27] Metamorphosed peridotite appears as serpentine along the west side of the Illinois River.[27] Chemically unsuited for growing plants, widespread serpentinite in the Klamaths supports sparse vegetation in parts of the watershed.[24] The Josephine peridotite was a source of valuable chromium ore, mined in the region between 1917 and 1960.[27]

At the mouth of the Rogue River, along the coast of Curry County, is the Otter Point Formation, a mélange of metamorphosed sedimentary rocks such as shales, sandstones, and chert. Although the rocks formed in the Jurassic, evidence suggests that they faulted north as part of the Gold Beach Terrane after the Klamaths merged with North America. Oregon's only dinosaur fragments, those of a hadrosaur or duck-billed dinosaur, were found here. In the mid-1960s, a geologist also discovered the beak and teeth of an ichthyosaur in the Otter Point Formation.[27] In 2018, a geologist from the University of Oregon found a toe bone of a plant-eating dinosaur near Mitchell in the east-central part of the state where the coast lay 100 million years ago. This discovery has also been billed as the first dinosaur fossil find in Oregon.[29]

History

editFirst peoples

editArchaeologists believe that the first humans to inhabit the Rogue River region were nomadic hunters and gatherers.[30] Radiocarbon dating suggests that they arrived in southwestern Oregon at least 8,500 years ago, and that at least 1,500 years before the first contact with whites, the natives established permanent villages along streams.[30] The home villages of various groups shared many cultural elements, such as food, clothing, and shelter types.[31] Intermarriage was common, and many people understood dialects of more than one of the three language groups spoken in the region.[31] The Native Americans (Indians) included Tututni people near the coast and, further upstream, groups of Shasta Costa, Upper Rogue River Athabaskan tribes (Dakubetede and Tal-tvsh-dan-ni), Shasta, Takelma, and Latgawa.[32] Houses in the villages varied somewhat, but were often about 12 feet (3.7 m) wide and 15 to 20 feet (4.6 to 6.1 m) long, framed with posts sunk into the ground, and covered with split sugar pine or red cedar planks.[33] People left the villages during about half of the year to gather camas bulbs, sugar-pine bark, acorns, and berries, and hunted deer and elk to supplement their main food, salmon.[34] The total early-1850s native population of southern Oregon, including the Umpqua, Coos, Coquille, and Chetco watersheds as well as the Rogue, is estimated to have been about 3,800.[30] The population before the arrival of explorers and European diseases is thought to have been at least one-third larger, but "there is insufficient evidence to estimate aboriginal populations prior to the time of first white contact... ".[30]

Culture clash

editThe first recorded encounter between whites and coastal southwestern Oregon Indians occurred in 1792 when British explorer George Vancouver anchored off Cape Blanco, about 30 miles (48 km) north of the mouth of the Rogue River, and Indians visited the ship in canoes.[35] In 1826, Alexander Roderick McLeod of the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) led an overland expedition from HBC's regional headquarters in Fort Vancouver to as far south as the Rogue [35] (4 miles inland) along with botanist David Douglas.[36]

In 1827, an HBC expedition led by Peter Skene Ogden made the first direct contact between whites and the inland Rogue River natives when he crossed the Siskiyou Mountains to look for beaver.[37] Friction between Indians and whites was relatively minor during these early encounters; however, in 1834, an HBC expedition led by Michel Laframboise was reported to have killed 11 Rogue River natives, and shortly thereafter a party led by an American trapper, Ewing Young, shot and killed at least two more.[35] The name Rogue River apparently began with French fur trappers who called the river La Riviere aux Coquins because they regarded the natives as rogues (coquins).[2][n 1] In 1835, Rogue River people killed four whites in a party of eight who were traveling from Oregon to California. Two years later, two of the survivors and others on a cattle drive organized by Young killed the first two Indians they met north of the Klamath River.[35]

The number of whites entering the Rogue River watershed greatly increased after 1846, when a party of 15 men led by Jesse Applegate developed a southern alternative to the Oregon Trail; the new trail was used by emigrants headed for the Willamette Valley.[39] Later called the Applegate Trail, it passed through the Rogue and Bear Creek valleys and crossed the Cascade Range between Ashland and south of Upper Klamath Lake.[40] From 90 to 100 wagons and 450 to 500 emigrants used the new trail later in 1846, passing through Rogue Indian homelands between the headwaters of Bear Creek and the future site of Grants Pass and crossing the Rogue about 4.5 miles (7.2 km) downstream of it.[41] Despite fears on both sides, violence in the watershed in the 1830s and 1840s was limited; "Indians seemed interested in speeding whites on their way, and whites were happy to get through the region without being attacked."[42]

In 1847, the Whitman massacre and the Cayuse War in what became southeastern Washington raised fears among white settlers throughout the region and led to the formation of large volunteer militias organized to fight Indians, though no whites were yet living in the Rogue River drainage.[43] Along the Rogue, tensions intensified in 1848 at the start of the California Gold Rush, when hundreds of men from the Oregon Territory passed through the Rogue Valley on their way to the Sacramento River basin.[44] After Indians attacked a group of returning miners along the Rogue in 1850, former territorial governor Joseph Lane negotiated a peace treaty with Apserkahar, a leader of the Takelma Indians. It promised protection of Indian rights and safe passage through the Rogue Valley for white miners and settlers.[45]

The peace did not last. Miners began prospecting for gold in the watershed, including a Bear Creek tributary called Jackson Creek, where they established a mining camp in 1852 at the site of what later became Jacksonville.[46] Indian attacks on miners that year led to U.S. Army intervention and fighting near Table Rock between Indians and the combined forces of professional soldiers and volunteer miner militias.[47] John P. Gaines, the new territorial governor, negotiated a new treaty with some but not all of the Indian bands, removing them from Bear Creek and other tributaries on the south side of the main stem.[47] At about the same time, more white emigrants, including women and children, were settling in the region. By 1852, about 28 donation land claims had been filed in the Rogue Valley.[48] Further clashes in 1853 led to the Treaty with the Rogue River (1853) that established the Table Rock Indian Reservation across the river from the federal Fort Lane.[49] As the white population increased and Indian losses of land, food sources, and personal safety mounted, bouts of violence upstream and down continued through 1854–55, culminating in the Rogue River War of 1855–56.[50]

Suffering from cold, hunger, and disease on the Table Rock Reservation, a group of Takelma returned to their old village at the mouth of Little Butte Creek in October 1855. After a volunteer militia attacked them, killing 23 men, women, and children, they fled downriver, attacking whites from Gold Hill to Galice Creek.[51] Confronted by volunteers and regular army troops, the Indians at first repulsed them; however, after nearly 200 volunteers launched an all-day assault on the remaining natives, the war ended at Big Bend (at RM 35 or RK 56) on the lower river.[51] By then, fighting had also ended near the coast, where, before retreating upstream, a separate group of natives had killed about 30 whites and burned their cabins near what later became Gold Beach.[52]

Most of the Rogue River Indians were removed in 1856 to reservations further north. About 1,400 were sent to the Coast Reservation, later renamed the Siletz Reservation.[53][54] To protect 400 natives still in danger of attack at Table Rock, Joel Palmer, the Oregon Superintendent of Indian Affairs, ordered their removal, involving a forced march of 33 days, to the newly established Grande Ronde Reservation in Yamhill County, Oregon.[55]

Mail boats

editAfter the Rogue River War, a small number of newcomers began to settle along or near the Rogue River Canyon. These pioneers, some of whom were white gold miners married to native Karok women from the Klamath River basin, established gardens and orchards, kept horses, cows, and other livestock, and received occasional shipments of goods sent by pack mule over the mountains.[56] Until the 1890s, these settlers remained relatively isolated from the outside world. In 1883, one of the settlers, Elijah H. Price, proposed a permanent mail route by boat up the Rogue River from Ellensburg (later renamed Gold Beach) to Big Bend, about 40 miles (64 km) upstream. The route, Price told the government, would serve perhaps 11 families and no towns.[57] Although the Post Office Department resisted the idea for many years, in early 1895 it agreed to a one-year trial of the water route, established a post office at Price's log cabin at Big Bend, and named Price postmaster. Price's job, for which he received no pay during the trial year, included running the post office and making sure that the mail boat made one round trip a week. He named the new post office Illahe.[58] The name derives from the Chinook Jargon word ilahekh, meaning "land" or "earth".[59]

Propelled by rowing, poling, pushing, pulling, and sometimes by sail, the mail boat delivered letters and small packages, including groceries from Wedderburn, where a post office was established later in 1895.[60] In 1897, the department established a post office near the confluence of the Rogue and the Illinois rivers, 8 miles (13 km) downriver from Illahe. The postmaster named the office Agnes after his daughter, but a transcription error added an extra "s" and the name became Agness.[60] Upriver, a third post office, established in 1903, was named Marial after another postmaster's daughter. Marial, at (RM) 48 (RK 77), is about 13 miles (21 km) upriver from Illahe and 21 miles (34 km) from Agness.[61] To avoid difficult rapids, carriers delivered the mail by mule between Illahe and Marial, and after 1908 most mail traveling beyond Agness went by mule. The Illahe post office closed in 1943,[62] and when the Marial post office closed in 1954, "it was the last postal facility in the United States to still be served only by mule pack trains."[63]

The first mail boat was an 18-foot (5.5 m), double-ended craft made of cedar.[60] By 1930, the mail-boat fleet consisted of three 26-foot (7.9 m) boats, equipped with 60-horsepower Model A Ford engines and designed to carry 10 passengers.[64] By the 1960s, rudderless jetboats powered by twin or triple 280-horsepower engines, began to replace propeller-driven boats. The jetboats could safely negotiate shallow riffles, and the largest could carry nearly 50 passengers.[65] Rogue mail-boat excursions, which had been growing more popular for several decades, began in the 1970s to include trips to as far upriver as Blossom Bar, 20 miles (32 km) above Agness.[66] As of 2010, jet boats, functioning mainly as excursion craft, still deliver mail between Gold Beach and Agness.[67] The Rogue River mail boat company is "one of only two mail carriers delivering the mail by boat in the United States";[68] the other is along the Snake River in eastern Oregon.[68][69]

Commercial fishing

editFor thousands of years, salmon was a reliable food source for Native Americans living along the Rogue. Salmon migrations were so huge that early settlers claimed they could hear the fish moving upstream. These large runs continued into the 20th century despite damage to spawning beds caused by gold mining in the 1850s and large-scale commercial fishing that began shortly thereafter. The fishing industry fed demands for salmon in the growing cities of Portland and San Francisco and for canned salmon in England.[38]

By the 1880s, Robert Deniston Hume of Astoria had bought land on both sides of the lower Rogue River and established such a big fishing business that he became known as the Salmon King of Oregon.[38][n 2] His fleet of gillnetting boats, controlling most of the anadromous fish population of the river, plied its lower 12 miles (19 km).[38] During his 32-year tenure, Hume's company caught, processed, and shipped hundreds of tons of salmon from the Rogue.[38] Upriver commercial fishermen also captured large quantities of fish. On a single day in 1913, Grants Pass crews using five drift boats equipped with gill nets caught 5,000 pounds (2,300 kg) of salmon.[38]

In 1877, in connection with his commercial fishery, Hume built a hatchery at Ellensburg (Gold Beach), which released fish into the river. In its first year of operation, Hume collected 215,000 salmon eggs and released about 100,000 fry.[72] After the first hatchery was destroyed by fire in 1893, Hume built a new hatchery in 1895, and in 1897 he co-operated with the United States Fish Commission in building and operating an egg-collecting station at the mouth of Elk Creek on the upper Rogue. In 1899, he built a hatchery near Wedderburn, across the river from Gold Beach, and until the time of his death in 1908 he had salmon eggs shipped to it from the Elk Creek station.[73][n 3]

Based on variations in the size of the yearly catch, Hume and others believed his methods of fish-propagation to be successful.[75][76] However, as salmon runs declined over time despite the hatcheries, recreational fishing interests began to oppose large-scale operations. In 1910, a state referendum banned commercial fishing on the Rogue, but this decision was reversed in 1913. As fish runs continued to dwindle, the state legislature finally closed the river to commercial fishing in 1935.[77]

As of 2010, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) operates the Cole M. Rivers Hatchery near the base of the dam at Lost Creek Lake, slightly upstream of the former Rogue–Elk Hatchery built by Hume. It raises rainbow trout (steelhead), Coho salmon, spring and fall Chinook salmon, and summer and winter steelhead.[78] The United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) built the hatchery in 1973 to offset the loss of fish habitat and spawning grounds in areas blocked by construction of the Lost Creek Dam on the main stem and the Applegate and Elk Creek dams on Rogue tributaries.[79] It is the third-largest salmon and steelhead hatchery in the United States.[80]

Celebrities

editIn 1926, author Zane Grey bought a miner's cabin at Winkle Bar, near the river.[81] He wrote Western books at this location,[81] including his 1929 novel Rogue River Feud.[82] Another of his books, Tales of Fresh Water Fishing (1928), included a chapter based on a drift-boat trip he took down the lower Rogue in 1925. The Trust for Public Land bought the property at Winkle Bar and transferred it in 2008 to the BLM, which made it accessible to the public.[83]

In the 1930s and 1940s, many other celebrities, attracted by the scenery, fishing, rustic lodges, and boat trips, visited the lower Rogue. Famous visitors included actors Clark Gable, Tyrone Power and Myrna Loy, singer Bing Crosby, author William Faulkner, journalist Ernie Pyle, radio comedians Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll, circus performer Emmett Kelly, and football star Norm van Brocklin.[84] Bobby Doerr, a Hall of Fame baseball player, married a teacher from Illahe, and made his home along the Rogue.[84] From 1940 to 1990, actress and dancer Ginger Rogers owned the 1,000-acre (400 ha) Rogue River Ranch, operated for many years as a dairy farm, near Eagle Point.[85] The historic Craterian Ginger Rogers Theater in Medford was named after her.[85] Actress Kim Novak and her veterinarian husband bought a home and 43 acres (17 ha) of land in 1997 near the Rogue River in Sams Valley, where they raise horses and llamas.[86]

Dams

editCurrent dams

editSince the removal of the Gold Ray Dam in 2010, there remain two dams on the main stem of the Rogue River.

William L. Jess Dam

editThe William L. Jess Dam, a huge flood-control and hydroelectric structure, blocks the Rogue River 157 miles (253 km) from its mouth.[87] Built by the USACE between 1972 and 1976, it impounds Lost Creek Lake.[88] The dam, which is 345 feet (105 m) high and 3,600 feet (1,100 m) long,[88] prevents salmon migration above this point.[79] When the lake is full, it covers 3,428 acres (1,387 ha) and has an average depth of 136 feet (41 m).[88] Ranked by storage capacity, its reservoir is the seventh-largest in Oregon.[89]

Prospect Nos. 1, 2, and 4 Hydroelectric Project

editThe only artificial barrier on the main stem of the Rogue upstream of Lost Creek Lake is a diversion dam at Prospect at RM 172 (RK 277). The concrete dam, 50 feet (15 m) high and 384 feet (117 m) wide, impounds water from the Rogue and nearby streams and diverts it to power plants, which return the water to the river further downstream. PacifiCorp operates this system, called The Prospect Nos. 1, 2, and 4 Hydroelectric Project. Built in pieces between 1911 and 1944, it includes separate diversion dams on the Middle Fork Rogue River and Red Blanket Creek, and a 9.25-mile (14.89 km) water-transport system of canals, flumes, pipes, and penstocks.[90]

Removed dams

editSeveral dams along the river's middle reaches were removed or destroyed during the first half of the 20th century.

After decades of controversy about water rights, costs, migratory fish, and environmental impacts, removal or modification of remaining middle-reach dams as well as a partly finished dam on Elk Creek, a major tributary of the Rogue, began in 2008. The de-construction projects were all meant to improve salmon runs by allowing more fish to reach suitable spawning grounds.[91]

Gold Ray Dam

editIn 1904, brothers C.R. and Frank Ray built the Gold Ray Dam, a log structure, to generate electricity near Gold Hill.[92] They installed a fish ladder.[92] The California-Oregon Power Company, which later became Pacific Power, acquired the dam in 1921.[92] Replacing the log dam in 1941 with a concrete structure 35 feet (11 m) high, it added a new fish ladder and a fish-counting station.[92] The company closed the hydroelectric plant in 1972, although the fish ladder remained, and biologists from the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife used the station to count migrating salmon and steelhead.[92] Jackson County, which owned the dam, had it removed with the help of a $5 million federal grant approved in June 2009.[93] The dam was demolished in the summer of 2010.[94]

Gold Hill Dam

editIn 2008, the city of Gold Hill removed the last of the Gold Hill Dam, a diversion dam slightly downstream of the Gold Ray Dam. Originally built to provide power for a cement company, it was 3 to 14 feet (0.91 to 4.27 m) high and 900 feet (270 m) long. The dam and a diversion canal later delivered municipal water to the city until Gold Hill installed a pumping station to supply its water.[95]

Savage Rapids Dam

editSavage Rapids Dam was 5 miles (8 km) upstream from Grants Pass. Built in 1921 to divert river flows for irrigation, the dam was 39 feet (12 m) tall and created a reservoir that seasonally extended up to 2.5 miles (4.0 km) upstream.[96] Its removal began in April 2009,[97] and was completed in October 2009.[98] Twelve newly installed pumps provide river water to the irrigation canals serving 7,500 acres (3,000 ha) of the Grants Pass Irrigation District (GPID).[97]

Ament Dam

editThe Ament Dam, built in 1902 by the Golden Drift Mining Company to provide water for mining equipment, was slightly upriver of Grants Pass. After the company failed to keep promises to provide irrigation and electric power to the vicinity and because the dam was a "massive fish killer", vigilantes destroyed part of the dam with dynamite in 1912. The damaged dam was completely removed before construction of the Savage Rapids Dam in 1921.[99]

Dam at Grants Pass

editIn 1890, the Grants Pass Power Supply Company had built a log dam 12 feet (3.7 m) high, across the river near the city. Salmon could pass the dam during high water, but most were blocked: "For half a mile below the dam, the river was crowded with fish throughout the summer."[100] After a flood destroyed this dam in 1905, it was replaced by a 6-foot (1.8 m) dam that, like its predecessor, lacked a fish ladder. By 1940, the dam had deteriorated to the point that it no longer blocked migratory fish.[100]

Dams on tributaries

editIn addition to the dams on the Rogue main stem, at one time or another "several hundred dams were built on tributaries within the range of salmon migration",[100] most of which supplied water for mining or irrigation. Before 1920, many of these dams made no provision for fish passage; public pressure as well as efforts by turn-of-the-century cannery owner R.D. Hume led to the installation of fish ladders on the most destructive dams.[100] As of 2005, there were about 80 non-hydroelectric dams, mostly small irrigation structures, in the Rogue basin.[101] In addition to Lost Creek Lake on the main stem, large reservoirs in the basin include Applegate Lake, Emigrant Lake, and Fish Lake.[101]

In 2008, USACE removed part of the Elk Creek Dam and restored Elk Creek to its original channel.[102] Construction on the dam had been halted by a court injunction in the 1980s after about 80 feet (24 m) of the proposed height of 240 feet (73 m) was reached.[102] Further controversy delayed the notching for two decades.[102] Elk Creek enters the Rogue River 5 miles (8.0 km) downstream from Lost Creek Lake.[103]

Bridges

editAmong the many bridges that cross the Rogue River is the Isaac Lee Patterson Bridge, which carries U.S. Route 101 over the river at Gold Beach. Designed by Conde B. McCullough and built in 1931, it is "one of the most notable bridges in the Pacific Northwest".[104] Named a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 1982 by the American Society of Civil Engineers, the 1,898-foot (579 m) structure was the first in the U.S. to use the Freyssinet method of stress control in concrete bridges. It features 7 open-spandrel 230-foot (70 m) arch spans, 18 deck-girder approach spans, and many ornate decorative features such as Art Deco entrance pylons.[104]

Several historic bridges cross the Rogue between Gold Hill and Grants Pass. The Gold Hill Bridge, designed by McCullough and built in 1927, is the only open-spandrel, barrel-arch bridge in Oregon. Its main arch is 143 feet (44 m) long.[105] Also designed by McCullough, the Rock Point Bridge carries U.S. Route 99 and Oregon Route 234 over the river near the unincorporated community of Rock Point. The 505-foot (154 m) structure has a single arch. Built in 1920 for $48,400, it replaced a wooden bridge at the same site.[106][107] The bridge was closed in September 2009 for repairs to its deck and railings. The project is expected to cost $3.9 million.[108]

Caveman Bridge in Grants Pass is a 550-foot (170 m), three-arch concrete structure. Designed by McCullough and built in 1931, it replaced the Robertson Bridge. The city calls the structure Caveman because the Redwood Highway (U.S. Route 199) that crosses the bridge passes near Oregon Caves National Monument,[109] about 50 miles (80 km) south of Grants Pass.

Slightly downstream of Grants Pass, the Robertson Bridge, built around 1909, is a 583-foot (178 m) three-span, steel, through-truss structure moved downriver in 1929 to make way for the Caveman Bridge. It carries the Rogue River Loop Highway (Oregon Route 260) over the river west of the city. The bridge was named for pioneers who settled in the area in the 1870s.[110]

Pollution

editTo comply with section 303(d) of the federal Clean Water Act, the EPA or its state delegates must develop a list of the surface waters in each state that do not meet approved water-quality criteria. To meet the criteria, the DEQ and others have developed Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) limits for pollutants entering streams and other surface waters.[111][n 4] The Oregon 303(d) list of pollutants for 2004–06 indicated that some reaches of the surface waters in the Rogue River basin did not meet the standards for temperature, bacteria, dissolved oxygen, sedimentation, pH and nuisance weeds and algae.[113] All of the listed stream reaches were in Oregon; none in the California part of the basin was listed as impaired on that state's 303(d) list in 2008.[114]

The EPA approved temperature TMDLs for three Rogue River tributaries: Upper Sucker Creek in 1999, Lower Sucker Creek in 2002, and Lobster Creek in 2002.[115] It approved temperature, sedimentation, and biological criteria TMDLs for the Applegate River basin in 2004, and temperature, sedimentation, fecal coliform, and Escherichia coli (E. coli) TMDLs for the Bear Creek watershed in 2007.[115] In 1992 it had approved pH, aquatic weeds and algae, and dissolved oxygen TMDLs for the Bear Creek watershed.[115] In December 2008, DEQ developed two TMDLs for the Rogue River basin (except the tributaries with their own TMDLs); a temperature TMDL was meant to protect salmon and trout from elevated water temperatures, and a fecal contamination TMDL was intended to safeguard people using surface waters for recreation.[116]

The DEQ has collected water-quality data in the Rogue basin since the mid-1980s and has used it to generate scores on the Oregon Water Quality Index (OWQI). The index is meant to provide an assessment of water quality for general recreational uses; OWQI scores can vary from 10 (worst) to 100 (ideal). Of the eight Rogue basin sites tested during the water years 1997–2006, five were ranked good, one was excellent, and two—Little Butte Creek and Bear Creek, in the most populated part of the Rogue basin—were poor.[115] On the Rogue River itself, scores varied from 92 at RM 138.4 (RK 222.7) declining to 85 at RM 117.2 (RK 188.6) but improving to 97 at RM 11.0 (RK 17.7).[115] By comparison, the average OWQI score for the Willamette River in downtown Portland, the state's largest city, was 74 between 1986 and 1995.[117]

Flora and fauna

editMost of the Rogue River watershed is in the Klamath Mountains ecoregion designated by the EPA, although part of the upper basin is in the Cascades ecoregion, and part of the lower basin is in the Coast Range ecoregion.[118] Temperate coniferous forests dominate much of the basin.[24] The upper basin, in the High Cascades and Western Cascades, is in places "identified as containing extremely high species richness within many groups of plants and animals".[24] Common tree species in the forests along the upper Rogue include incense cedar, white fir, and Shasta red fir.[118]

Further downstream a diverse mix of conifers, broadleaf evergreens, and deciduous trees and shrubs grow in parts of the basin. In more populated areas, orchards, cropland, and pastureland have largely replaced the original vegetation, although remnants of oak savanna, prairie vegetation, and seasonal ponds survive at Table Rocks north of Medford. Oak woodlands, grassland savanna, ponderosa pine, and Douglas-fir thrive in the relatively dry foothills east of Medford; areas in the foothills of the Illinois Valley support Douglas-fir, madrone, and incense cedar. Parts of the Illinois River watershed have sparse vegetation including Jeffrey pine and oak and ceanothus species that grow in serpentine soils.[118] The Klamath-Siskiyou region of northern California and southwestern Oregon, including parts of the southwestern Rogue basin, is among the four most diverse temperate coniferous forests in the world.[24] Considered one of the global centers of biodiversity, it contains about 3,500 different plant species.[24] The Klamath-Siskiyou region is one of seven International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) areas of global botanical significance in North America and has been proposed as a World Heritage Site and UNESCO Biosphere Reserve.[119]

The lower Rogue passes through the Southern Oregon Coast Range, where forests include Douglas-fir, western hemlock, tanoak, Port Orford cedar, and western redcedar, and at lower elevations Sitka spruce.[118] Coastal forests extending from British Columbia in the north to Oregon (and the Rogue) in the south are "some of the most productive in the world".[24] The coastal region, where it has not been altered by humans, abounds with ferns, lichens, mosses, and herbs, as well as conifers.[24]

The Rogue River contains "extremely high-quality salmonid habitat and has one of the finest salmonid fisheries in the west. However, most stocks are less abundant than they were historically... ".[120] Salmonids found in the Rogue River downstream of Lost Creek Lake include Coho salmon, spring and fall Chinook salmon, and summer and winter steelhead. Other native species of freshwater fish found in the watershed include coastal cutthroat trout, Pacific lamprey, green sturgeon, white sturgeon, Klamath smallscale sucker, speckled dace, prickly sculpin, and riffle sculpin. Nonnative species include redside shiner, largemouth bass, smallmouth bass, black crappie, bluegill, catfish, brown bullhead, yellow perch, carp, goldfish, American shad, Umpqua pikeminnow, and species of trout.[121] Coho salmon in the watershed belong to an Evolutionarily Significant Unit (ESU) that was listed by the National Marine Fisheries Service as a threatened species in 1997 and reaffirmed as threatened in 2005.[121] The state of Oregon in 2005 listed Rogue spring Chinook salmon as potentially at risk.[121]

Trees and shrubs growing in the riparian zones along the Rogue River include willows, red alder, white alder, black cottonwood, and Oregon ash.[24] A few of the common animal and bird species seen along the river are American black bear, North American river otter, black-tailed deer, bald eagle, osprey, great blue heron, water ouzel, and Canada goose.[11]

Recreation

editBoating

editSoggy Sneakers: A Paddler's Guide to Oregon's Rivers lists several whitewater runs of varying difficulty along the upper, middle, and lower Rogue River and its tributaries. The longest run, on the main stem of the river downstream of Grants Pass, is "one of the best-known whitewater runs in the United States".[82] Popular among kayakers and rafters, the 35-mile (56 km) run consists of class 3+ rapids separated by more gentle stretches and deep pools. Its entire length is classified Wild and Scenic.[82]

The Wild section of the lower Rogue River runs for 33.8 miles (54.4 km) between Grave Creek and Watson Creek. To protect the river from overuse, a maximum of 120 commercial and noncommercial users a day are allowed to run this section. To enter it, boaters must obtain a special-use permit allocated through a random-selection process and pick it up at the Smullin Visitor Center, about 20 miles (32 km) west of Interstate 5 on the Merlin–Galice Road, at the Rand Ranger Station downstream of Galice.[122] Other sections of the river are open to jetboats. A Gold Beach company offers commercial jetboat trips of up to 104 miles (167 km) round-trip on the lower Rogue River.[67] Another company offers jetboat excursions on the Hellgate section of the river below Grants Pass.[123]

Hiking

editThe Upper Rogue River Trail, a National Recreation Trail, closely follows the river for about 40 miles (64 km) from its headwaters at the edge of Crater Lake National Park to the boundary of the Rogue River National Forest at the mountain community of Prospect. Highlights along the trail include a river canyon cut through pumice deposited by the explosion of Mount Mazama about 8,000 years ago; the Rogue Gorge, lined with black lava, and Natural Bridge, where the river flows through a 250-foot (76 m) lava tube. Between Farewell Bend and Natural Bridge, the trail passes through the Union Creek Historic District, a site with early 20th-century resort buildings and a former ranger station that are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[12]

The Lower Rogue River Trail, a National Recreation Trail of 40 miles (64 km), runs parallel to the river from Grave Creek to Illahe, in the Wild Rogue Wilderness, 27 miles (43 km) northwest of Grants Pass. The roadless area through which the trail runs is managed by the Siskiyou National Forest and the Medford District of the federal Bureau of Land Management and covers 224 square miles (580 km2) including 56 square miles (150 km2) of designated federal wilderness. Backpackers use the trail for multiple-day trips, while day hikers take shorter trips. In addition to scenery and wildlife, features include views of rapids and "frantic boaters",[81] lodges at Illahe, Clay Hill Rapids, Paradise Creek, and Marial, and the Rogue River Ranch and museum. Hikers can take jet boats from Gold Beach to some of the lodges between May and November. The trail connects to many shorter side trails as well as to the 27-mile (43 km) Illinois River Trail south of Agness.[81] Hikers can also take trips along the Rogue that combine backpacking and rafting.[124]

Rogue River Trail 1168 continues west 12 miles (19 km) along the north side of the river from Agness to the Morey Meadow Trailhead. Forest Road 3533 provides a hiking route between the trailhead and the Lobster Creek Bridge, 5.8 miles (9 km) further west. The Rogue River Walk is about a 6-mile (10 km) trail along the south side of the river continues west to a trailhead about 4.7 miles (8 km) east of Gold Beach.[125][126]

Fishing

editSport fishing on the Rogue River varies greatly depending on the location. In many places, fishing is good from stream banks and gravel bars, and much of the river is also fished from boats. Upstream of Lost Creek Lake, the main stem, sometimes called the North Fork, supports varieties of trout. Between Lost Creek Lake and Grants Pass there are major fisheries for spring and fall Chinook salmon, and Coho salmon from hatcheries, summer and winter steelhead, and large resident rainbow trout. The river between Grants Pass and Grave Creek has productive runs of summer and winter steelhead and Chinook, as well as good places to fish for trout. From Grave Creek to Foster Bar, all but the lower 15 miles (24 km) of which is closed to jetboats, anglers fish for summer and winter steelhead, spring and fall Chinook, and Coho. Near Agness, the river produces large catches of immature steelhead known as "half-pounders" that return from the ocean to the river in August in large schools. The lower river has spring and fall Chinook, as well as perch, lingcod, and crab near the ocean.[127]

Parks

editParks along the Rogue River, which begins in the northwest corner of Crater Lake National Park, include Prospect State Scenic Viewpoint, a forested area 1 mile (1.6 km) south of Prospect with a hiking trail leading to waterfalls and the Rogue River.[128] The Joseph H. Stewart State Recreation Area has campsites overlooking Lost Creek Lake.[129] Casey State Recreation Site offers boating, fishing, and picnic areas along the river 29 miles (47 km) northeast of Medford.[130] TouVelle State Recreation Site is a day-use park along the river at the base of Table Rocks and adjacent to the Denman Wildlife Area, about 9 miles (14 km) north of Medford.[131] Valley of the Rogue State Park, 12 miles (19 km) east of Grants Pass, is built around 3 miles (4.8 km) of river shoreline.[132]

Between Grants Pass and the Hellgate Recreation Area, Josephine County manages two parks, Tom Pearce and Schroeder, along the river.[133] Hellgate, 27 miles (43 km) long, begins at the confluence of the Rogue and Applegate rivers about 7 miles (11 km) west of Grants Pass. This stretch of the Rogue, featuring class I and II rapids, 11 access points for boats, 4 parks and campgrounds managed by Josephine County, ends at Grave Creek, where the Wild Rogue Wilderness begins.[134] Indian Mary Park, part of the Josephine County park system, has tent sites, yurts, and spaces for camping vehicles on 61 acres (25 ha) along the Merlin–Galice road at Merlin.[135] The other three Josephine County parks in the Hellgate Recreation Area are Whitehorse, across from the mouth of the Applegate River; Griffin, slightly downstream of Whitehorse, and Almeda, downstream of Indian Mary.[133]

See also

editNotes and references

editNotes

- ^ The Oregon Territorial Legislature changed the name to Gold River in 1854, but in response to opposition from Rogue River settlers changed it back to Rogue River a year later.[38]

- ^ An economic study and biography, The Salmon King of Oregon: R.D. Hume and the Pacific Fisheries, in a chapter titled "The Curry County Domain", describes Hume's involvement in shipping, retail merchandising, real-estate transactions, the Wedderburn post office, the hotel and saloon business, a race track, and other Curry County enterprises as well as business directly related to propagating, catching, and canning fish.[70] Hume referred to himself as a "pygmy monopolist" in his autobiography, published in the Wedderburn Radium newspaper (which he owned) between February 1904 and June 1906.[71]

- ^ To protect the eggs from hatching en route, they were packed in crates of wet moss, and the crates were packed in boxes filled with ice and sawdust. The boxes were shipped by horse-drawn wagon to Medford, then by train to Portland or San Francisco, then by steamer to Hume's hatchery 150 miles (240 km) downstream from the egg-collecting station.[38] The eggs could not be shipped via the Rogue itself because parts of it were largely unnavigable.[74]

- ^ The TMDL limits for the Rogue River depend on a combination of biological, natural, and human-use criteria that vary from place to place. For example, the Rogue basin temperature standard approved by the EPA in 2004 says in part that "The seven-day-average maximum temperature of a stream identified as having salmon and steelhead spawning use on subbasin maps and tables set out in [government documents] may not exceed 13.0 degrees Celsius (55.4 degrees Fahrenheit) at the times indicated on these [documents]".[112] Different criteria and temperature limits apply to parts of the river that are not used by these particular fish for spawning, and other variables affect the TMDLs as well.[112]

References

- ^ a b c "Rogue River". Geographic Names Information System (GNIS). United States Geological Survey. November 28, 1980. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ a b McArthur & McArthur 2003, p. 822.

- ^ a b Google Earth elevation for GNIS coordinates

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Hamaker Butte, Oregon quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved April 15, 2009. The map includes a river mile (RM) marker for RM 211 (river kilometer 346) near the confluence of the Rogue River with Mazama Creek.

- ^ a b Crown et al. 2008, p. i, summary.

- ^ a b c "Water-data report 2007: 14372300 Rogue River near Agness, OR" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ^ "National Wild and Scenic Rivers System" (PDF). rivers.gov. National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2023-01-06. Retrieved 2023-01-05.

- ^ Confederated Tribes of Siletz (2007). "Siletz Talking Dictionary". Swarthmore College. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ Fattig, Paul (August 16, 1998). "Bits of Lost Takelma Language Preserved". Mail Tribune. Medford, Oregon: Local Media Group. Archived from the original on 2016-03-09. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ^ Oregon Atlas and Gazetteer (Map) (1991 ed.). DeLorme Mapping. § 17, 18, 20, 25–29, 37. ISBN 0-89933-235-8.

- ^ a b c "The Rogue River". U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved April 15, 2009.

- ^ a b c "Recreation: Wild and Scenic Rogue River (Upper)". United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service, Rogue River–Siskiyou National Forest. 2006. Archived from the original on September 5, 2010. Retrieved April 29, 2009.

- ^ a b Allan, Buckley & Meacham 2001, pp. 162–63.

- ^ "Water-data report 2007: 14330000 Rogue River below Prospect, OR" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved April 25, 2009.

- ^ "Water-data report 2007: 14339000 Rogue River at Dodge Bridge, near Eagle Point, OR" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved April 24, 2009.

- ^ "Water-data report 2007: 14359000 Rogue River at Raygold, near Central Point, OR" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved April 24, 2009.

- ^ "Water-data report 2007: 14361500 Rogue River at Grants Pass, OR" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved April 24, 2009.

- ^ "Oregon's Top 10 Weather Events of 1900s". National Weather Service. Archived from the original on May 6, 2017. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ a b Crown et al. 2008, pp. ii, summary.

- ^ Allan, Buckley & Meacham 2001, p. 168.

- ^ a b c d e Crown et al. 2008, pp. 2–3, chapter 1.

- ^ California Atlas & Gazetteer (Map) (2008 ed.). DeLorme. § 23–24. ISBN 0-89933-383-4.

- ^ Carter & Resh 2005, p. 584.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Carter & Resh 2005, pp. 568–73.

- ^ "Geomorphic Provinces: Cascades Province – High Cascades". United States Forest Service. 2005. Archived from the original on April 9, 2005. Retrieved August 14, 2009.

- ^ "Geomorphic Provinces: Cascade Range – Western Cascades". United States Forest Service. Archived from the original on April 9, 2005. Retrieved August 14, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Bishop 2003, pp. 52–56.

- ^ a b Orr & Orr 1999, pp. 51–78.

- ^ Ross, Erin (November 20, 2018). "Meet The 'Mitchell Ornithopod': Oregon's 1st Dinosaur Fossil Find". Oregon Public Broadcasting. Archived from the original on November 22, 2018. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Douthit 2002, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b Schwartz 1997, p. 5.

- ^ Schwartz 1997, p. 7.

- ^ Schwartz 1997, p. 13.

- ^ Schwartz 1997, pp. 15–17.

- ^ a b c d Schwartz 1997, pp. 20–25.

- ^ "ORWW Coquelle Trails: History: McLeod 1826-1827".

- ^ Douthit 2002, pp. 11–19.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dorband 2006, pp. 58–63.

- ^ Douthit 2002, p. 58.

- ^ Allan, Buckley & Meacham 2001, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Douthit 2002, p. 60.

- ^ Douthit 2002, p. 63.

- ^ Douthit 2002, pp. 66–68.

- ^ Schwartz 1997, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Douthit 2002, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Douthit 2002, pp. 78–80.

- ^ a b Douthit 2002, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Douthit 2002, p. 80.

- ^ Douthit 2002, p. 106.

- ^ Douthit 2002, pp. 124–32.

- ^ a b Atwood, Kay; Gray, Dennis J. (2003). "Where Living Waters Flow: Place & People: War & Removal". Oregon Historical Society. Archived from the original on February 13, 2015. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

- ^ Douthit 2002, pp. 150–153.

- ^ Schwartz 1997, pp. 146–49.

- ^ Douthit 2002, pp. 157–58.

- ^ Douthit 2002, pp. 147, 163.

- ^ Meier & Meier 1995, p. 9.

- ^ Meier & Meier 1995, p. 13.

- ^ Meier & Meier 1995, pp. 18–19.

- ^ McArthur & McArthur 2003, p. 495.

- ^ a b c Meier & Meier 1995, pp. 20–25.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Marial, Oregon quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- ^ Meier & Meier 1995, p. 80.

- ^ Meier & Meier 1995, p. 28.

- ^ Meier & Meier 1995, p. 58.

- ^ Meier & Meier 1995, pp. 103–08.

- ^ Meier & Meier 1995, pp. 121–23.

- ^ a b "Gold Beach Jet Boat Rivalry Ends with Sale of Mail Boats". Curry County Pilot. Western Communications. March 3, 2010.

- ^ a b Meier & Meier 1995, p. 150.

- ^ "On Snake River, Residents Get Mail by Rapid Delivery". The Seattle Times. The Seattle Times Company. Associated Press. December 27, 2007. Archived from the original on March 16, 2016. Retrieved June 1, 2009.

- ^ Dodds 1959, pp. 44–70.

- ^ Dodds 1959, p. 3.

- ^ Taylor 1999, p. 206.

- ^ Dodds 1959, p. 132.

- ^ Dodds 1959, p. 155.

- ^ "Pacific Coast Fisheries, Interesting Facts about the Methods of Work" (PDF). The New York Times. May 22, 1892. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- ^ Dodds 1959, pp. 239–40.

- ^ Cain, Allen (2002). "News Editorial, Nets vs. Development (Curry County Reporter, August 15, 1935)". Oregon Historical Society. Archived from the original on October 7, 2015. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- ^ "The ODFW Visitors' Guide, Southwest Region: Cole M. Rivers Hatchery". Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. 2010. Archived from the original on July 1, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- ^ a b "Cole Rivers Hatchery Operations Plan 2009" (PDF). Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-04. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

- ^ Bannan 2002, pp. 152–53.

- ^ a b c d Sullivan 2002, pp. 187–93.

- ^ a b c Giordano 2004, pp. 120–22.

- ^ LaLande, Jeff (2009). "Zane Grey (1872–1939)". The Oregon Encyclopedia. Portland State University. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- ^ a b Meier, pp. 73–79

- ^ a b "Notable Oregonians: Ginger Rogers – Actress, Dancer". Oregon State Archives. 2009. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ^ "Notable Oregonians: Kim Novak – Actress". Oregon State Archives. 2009. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: McLeod, Oregon, quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ a b c Johnson et al. 1985, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Johnson et al. 1985, p. 171.

- ^ United States Department of Energy, Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (April 8, 2008). "Order Issuing New License: PacifiCorp Project No. 2630-004" (PDF). Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- ^ Preusch, Matthew (June 8, 2008). "Epic Rogue River Near Reversal of Fortune". The Oregonian. Portland, Oregon: Oregon Live LLC. Retrieved April 26, 2009 – via NewsBank.

- ^ a b c d e Freeman, Mark (March 22, 2009). "Stimulus Spurs County on Gold Ray Dam Removal". Mail Tribune. Medford, Oregon: Southern Oregon Media Group. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved April 26, 2009.

- ^ Fattig, Paul (June 30, 2009). "Stimulus Money Pays for Rogue River Dam Removal". Mail Tribune. Medford, Oregon: Southern Oregon Media Group.

- ^ Brown, Lisa (September 13, 2010). "Gold Ray Dam Comes Down". Waterwatch. Archived from the original on November 16, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2012.

- ^ "Gold Hill Dam Removal". River Design Group. 2008. Archived from the original on October 8, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ Bureau of Reclamation. "Savage Rapids Dam, Rogue River Near Grants Pass, Oregon". United States Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on June 17, 2015. Retrieved April 26, 2009.

- ^ a b Associated Press (April 7, 2009). "Rogue River Dam to Be Removed". The Seattle Times. Seattle: The Seattle Times Company. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- ^ "River Runs Wilder Now That Dam Is Gone". NBC News. Associated Press. October 10, 2009. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ^ Dorband 2006, p. 62.

- ^ a b c d Lichatowich 1999, p. 77.

- ^ a b Carter & Resh 2005, p. 571.

- ^ a b c McKechnie, Ralph (October 20, 2008). "Corps Complete Notching of Elk Creek Dam". Upper Rogue Independent. Eagle Point, Oregon: Upper Rogue Independent. Archived from the original on 2011-07-17. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Trail, Oregon, quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ a b Smith, Norman & Dykman 1989, p. 106.

- ^ Smith, Norman & Dykman 1989, p. 103.

- ^ Smith, Norman & Dykman 1989, p. 93.

- ^ Miller, Bill (April 13, 2008). "Rock Point Bridge Over Rogue River". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ Specht, Sanne (April 14, 2010). "One Lane of Historic Bridge Will Open by Memorial Day". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ Smith, Norman & Dykman 1989, p. 105.

- ^ Smith, Norman & Dykman 1989, p. 270.

- ^ Crown et al. 2008, pp. i–ii, summary.

- ^ a b Crown et al. 2008, pp. 1–12, chapter 1.

- ^ Crown et al. 2008, p. 9, chapter 1.

- ^ Crown et al. 2008, p. 1, chapter 1.

- ^ a b c d e Crown et al. 2008, pp. 10–11, chapter 1.

- ^ Crown et al. 2008, p. 2, chapter 1.

- ^ Wade, Curtis. "Tualatin Subbasin". Oregon Water Quality Index Report for Lower Willamette, Sandy, and Lower Columbia Basins: Water Years 1986–1995. Oregon Department of Environmental Quality. Archived from the original on April 30, 2015. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Thorson, T.D.; Bryce, S.A.; Lammers, D.A.; et al. (2003). "Ecoregions of Oregon (front side of color poster with map, descriptive text, summary tables, and photographs)" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved April 5, 2010.[permanent dead link] Reverse side here [1][permanent dead link]

- ^ "Klamath–Siskiyou". World Wildlife Fund. Archived from the original on March 3, 2014. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ Carter & Resh 2005, p. 572.

- ^ a b c Crown et al. 2008, pp. 6–7, chapter 1.

- ^ "Rogue River Boater's Guide: 50th Anniversary Edition" (PDF). United States Bureau of Land Management and United States Forest Service. 2004. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ^ Dorband 2006, pp. 105–06.

- ^ "National Geographic Adventure: Orange Torpedo Trips". National Geographic Society. 2010. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ "Discover the Rogue River Walk" (PDF). Oregon Chapter of the Sierra Club. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ "Rogue River Trail - Oregon California Coast". Oregon California Coast. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ Sheehan 2005, pp. 82–93.

- ^ "Prospect State Scenic Viewpoint". Oregon Parks and Recreation Department. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ "Joseph H. Stewart State Recreation Area". Oregon Parks and Recreation Department. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ^ "Casey State Recreation Site". Oregon Parks and Recreation Department. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ^ "TouVelle State Recreation Site". Oregon Parks and Recreation Department. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ "Valley of the Rogue State Park". Oregon Parks and Recreation Department. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ a b "Josephine County Parks map". Josephine County Parks. Archived from the original on November 7, 2007. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ "Hellgate Recreation Area". Bureau of Land Management. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ "Indian Mary: The Centerpiece of the Josephine County Park System". Josephine County Parks. Archived from the original on April 3, 2016. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

Sources

edit- Allan, Stuart; Buckley, Aileen R.; Meacham, James E. (2001) [1976]. Loy, William G. (ed.). Atlas of Oregon (2nd ed.). Eugene, Oregon: University of Oregon Press. ISBN 0-87114-101-9.

- Bannan, Jan (2002) [1993]. Oregon State Parks (2nd ed.). Seattle: The Mountaineers Books. ISBN 0-89886-794-0.

- Bishop, Ellen Morris (2003). In Search of Ancient Oregon: A Geological and Natural History. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. ISBN 978-0-88192-789-4.

- Carter, James L.; Resh, Vincent H. (2005). "Chapter 12: Pacific Coast Rivers of the Coterminous United States". In Benke, Arthur C.; Cushing, Colbert E. (eds.). Rivers of North America. Burlington, Massachusetts: Elsevier Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-088253-1.

- Crown, Julia; Meyers, Bill; Tugaw, Heather; Turner, Daniel (2008). "Rogue River Basin TMDL: Chapter 1 and Executive Summary" (PDF). Salem, Oregon: Oregon Department of Environmental Quality. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 26, 2014. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

- Dodds, Gordon B. (1959). The Salmon King of Oregon: R.D. Hume and the Pacific Fisheries. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. OCLC 469312613.

- Dorband, Roger (2006). The Rogue: Portrait of a River. Portland, Oregon: Raven Studios. ISBN 0-9728609-3-2.

- Douthit, Nathan (2002). Uncertain Encounters: Indians and Whites at Peace and War in Southern Oregon. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press. ISBN 0-87071-549-6.

- Giordano, Pete (2004). Soggy Sneakers: A Paddler's Guide to Oregon's Rivers (4th ed.). Seattle: The Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-0-89886-815-9.

- Johnson, Daniel M.; Petersen, Richard R.; Lycan, D. Richard; Sweet, James W.; Neuhaus, Mark E. (1985). Atlas of Oregon Lakes. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press. ISBN 0-87071-343-4.

- Lichatowich, James A. (1999). Salmon Without Rivers: A History of the Pacific Salmon Crisis. Washington, D.C.: Island Press. ISBN 1-55963-361-1.

- McArthur, Lewis A.; McArthur, Lewis L. (2003) [1928]. Oregon Geographic Names (7th ed.). Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-87595-277-1.

- Meier, Gary; Meier, Gloria (1995). Whitewater Mailmen: The Story of the Rogue River Mail Boats. Bend, Oregon: Maverick Publications. ISBN 0-89288-216-6.

- Orr, Elizabeth L.; Orr, William N. (1999). Geology of Oregon (5th ed.). Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. ISBN 0-7872-6608-6.

- Schwartz, E. A. (1997). The Rogue River Indian War and Its Aftermath, 1850–1980. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2906-9.

- Sheehan, Madelynne Diness (2005). Fishing in Oregon: The Complete Oregon Fishing Guide (10th ed.). Scappoose, Oregon: Flying Pencil Publications. ISBN 0-916473-15-5.

- Smith, Dwight A.; Norman, James B.; Dykman, Pieter T. (1989) [1986]. Historic Highway Bridges of Oregon (2nd ed.). Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-87595-205-4.

- Sullivan, William L. (2002). Exploring Oregon's Wild Areas (3rd ed.). Seattle: The Mountaineers Press. ISBN 0-89886-793-2.

- Taylor, Joseph E. III (1999). Making Salmon: An Environmental History of the Northwest Fisheries Crisis. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-98114-8.

External links

edit- Bureau of Land Management: "Guide to Floating the Rogue"

- Bureau of Land Management: Rogue National Wild and Scenic River

- Esri.com: Map of the Prospect Hydroelectric Project

- The Oregon Encyclopedia: Robert Deniston Hume bio

- River of the Rogues Archived 2019-07-11 at the Wayback Machine — documentary produced by Oregon Field Guide.

- Rogue Basin Partnership

- Rogue National Wild and Scenic River - BLM page