The Doric order is one of the three orders of ancient Greek and later Roman architecture; the other two canonical orders were the Ionic and the Corinthian. The Doric is most easily recognized by the simple circular capitals at the top of the columns. Originating in the western Doric region of Greece, it is the earliest and, in its essence, the simplest of the orders, though still with complex details in the entablature above.

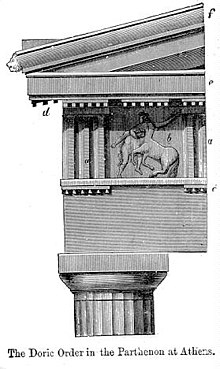

The Greek Doric column was fluted,[1] and had no base, dropping straight into the stylobate or platform on which the temple or other building stood. The capital was a simple circular form, with some mouldings, under a square cushion that is very wide in early versions, but later more restrained. Above a plain architrave, the complexity comes in the frieze, where the two features originally unique to the Doric, the triglyph and gutta, are skeuomorphic memories of the beams and retaining pegs of the wooden constructions that preceded stone Doric temples.[2] In stone they are purely ornamental.

The relatively uncommon Roman and Renaissance Doric retained these, and often introduced thin layers of moulding or further ornament, as well as often using plain columns. More often they used versions of the Tuscan order, elaborated for nationalistic reasons by Italian Renaissance writers, which is in effect a simplified Doric, with un-fluted columns and a simpler entablature with no triglyphs or guttae. The Doric order was much used in Greek Revival architecture from the 18th century onwards; often earlier Greek versions were used, with wider columns and no bases to them.

The ancient architect and architectural historian Vitruvius associates the Doric with masculine proportions (the Ionic representing the feminine).[3][4] It is also normally the cheapest of the orders to use. When the three orders are superposed, it is usual for the Doric to be at the bottom, with the Ionic and then the Corinthian above, and the Doric, as "strongest", is often used on the ground floor below another order in the storey above.[5]

History

editGreek

editIn their original Greek version, Doric columns stood directly on the flat pavement (the stylobate) of a temple without a base. With a height only four to eight times their diameter, the columns were the most squat of all the classical orders; their vertical shafts were fluted with 20 parallel concave grooves, each rising to a sharp edge called an arris. They were topped by a smooth capital that flared from the column to meet a square abacus at the intersection with the horizontal beam (architrave) that they carried.

The Parthenon has the Doric design columns. It was most popular in the Archaic Period (750–480 BC) in mainland Greece, and also found in Magna Graecia (southern Italy), as in the three temples at Paestum. These are in the Archaic Doric, where the capitals spread wide from the column compared to later Classical forms, as exemplified in the Parthenon.

Pronounced features of both Greek and Roman versions of the Doric order are the alternating triglyphs and metopes. The triglyphs are decoratively grooved with two vertical grooves ("tri-glyph") and represent the original wooden end-beams, which rest on the plain architrave that occupies the lower half of the entablature. Under each triglyph are peglike "stagons" or "guttae" (literally: drops) that appear as if they were hammered in from below to stabilize the post-and-beam (trabeated) construction. They also served to "organize" rainwater runoff from above. The spaces between the triglyphs are the "metopes". They may be left plain, or they may be carved in low relief.[6]

Spacing the triglyphs

editThe spacing of the triglyphs caused problems which took some time to resolve. A triglyph is centered above every column, with another (or sometimes two) between columns, though the Greeks felt that the corner triglyph should form the corner of the entablature, creating an inharmonious mismatch with the supporting column.

The architecture followed rules of harmony. Since the original design probably came from wooden temples and the triglyphs were real heads of wooden beams, every column had to bear a beam which lay across the centre of the column. Triglyphs were arranged regularly; the last triglyph was centred upon the last column (illustration, right: I.). This was regarded as the ideal solution which had to be reached.

Changing to stone cubes instead of wooden beams required full support of the architrave load at the last column. At the first temples the final triglyph was moved (illustration, right: II.), still terminating the sequence, but leaving a gap disturbing the regular order. Even worse, the last triglyph was not centered with the corresponding column. That "archaic" manner was not regarded as a harmonious design. The resulting problem is called the doric corner conflict. Another approach was to apply a broader corner triglyph (III.) but was not really satisfying.

Because the metopes are somewhat flexible in their proportions, the modular space between columns ("intercolumniation") can be adjusted by the architect. Often the last two columns were set slightly closer together (corner contraction), to give a subtle visual strengthening to the corners. That is called the "classic" solution of the corner conflict (IV.). Triglyphs could be arranged in a harmonic manner again, and the corner was terminated with a triglyph, though the final triglyph and column were often not centered. Roman aesthetics did not demand that a triglyph form the corner, and filled it with a half (demi-) metope, allowing triglyphs centered over columns (illustration, right, V.).

Temples

editThere are many theories as to the origins of the Doric order in temples. The term Doric is believed to have originated from the Greek-speaking Dorian tribes.[7] One belief is that the Doric order is the result of early wood prototypes of previous temples.[8] With no hard proof and the sudden appearance of stone temples from one period after the other, this becomes mostly speculation. Another belief is that the Doric was inspired by the architecture of Egypt.[9] With the Greeks being present in Ancient Egypt as soon the 7th-century BC, it is possible that Greek traders were inspired by the structures they saw in what they would consider foreign land. Finally, another theory states that the inspiration for the Doric came from Mycenae. At the ruins of this civilization lies architecture very similar to the Doric order. It is also in Greece, which would make it very accessible.

Right image: Doric anta capital at the Athenian Treasury (c. 500 BC).

Some of the earliest examples of the Doric order come from the 7th-century BC. These examples include the Temple of Apollo at Corinth and the Temple of Zeus at Nemea.[10] Other examples of the Doric order include the three 6th-century BC temples at Paestum in southern Italy, a region called Magna Graecia, which was settled by Greek colonists. Compared to later versions, the columns are much more massive, with a strong entasis or swelling, and wider capitals.

The Temple of the Delians is a "peripteral" Doric order temple, the largest of three dedicated to Apollo on the island of Delos. It was begun in 478 BC and never completely finished. During their period of independence from Athens, the Delians reassigned the temple to the island of Poros. It is "hexastyle", with six columns across the pedimented end and thirteen along each long face. All the columns are centered under a triglyph in the frieze, except for the corner columns. The plain, unfluted shafts on the columns stand directly on the platform (the stylobate), without bases. The recessed "necking" in the nature of fluting at the top of the shafts and the wide cushionlike echinus may be interpreted as slightly self-conscious archaising features, for Delos is Apollo's ancient birthplace. However, the similar fluting at the base of the shafts might indicate an intention for the plain shafts to be capable of wrapping in drapery.

A classic statement of the Greek Doric order is the Temple of Hephaestus in Athens, built about 447 BC. The contemporary Parthenon, the largest temple in classical Athens, is also in the Doric order, although the sculptural enrichment is more familiar in the Ionic order: the Greeks were never as doctrinaire in the use of the Classical vocabulary as Renaissance theorists or Neoclassical architects. The detail, part of the basic vocabulary of trained architects from the later 18th century onwards, shows how the width of the metopes was flexible: here they bear the famous sculptures including the battle of Lapiths and Centaurs.

Roman

editIn the Roman Doric version, the height of the entablature has been reduced. The endmost triglyph is centered over the column rather than occupying the corner of the architrave. The columns are slightly less robust in their proportions. Below their caps, an astragal molding encircles the column like a ring. Crown moldings soften transitions between frieze and cornice and emphasize the upper edge of the abacus, which is the upper part of the capital.

Roman Doric columns also have moldings at their bases and stand on low square pads or are even raised on plinths. In the Roman Doric mode, columns are not usually fluted; indeed, fluting is rare. Since the Romans did not insist on a triglyph covered corner, now both columns and triglyphs could be arranged equidistantly again and centered together. The architrave corner needed to be left "blank", which is sometimes referred to as a half, or demi-, metope (illustration, V., in Spacing the Columns above).

The Roman architect Vitruvius, following contemporary practice, outlined in his treatise the procedure for laying out constructions based on a module, which he took to be one half a column's diameter, taken at the base. An illustration of Andrea Palladio's Doric order, as it was laid out, with modules identified, by Isaac Ware, in The Four Books of Palladio's Architecture (London, 1738) is illustrated at Vitruvian module.

According to Vitruvius, the height of Doric columns is six or seven times the diameter at the base.[11] This gives the Doric columns a shorter, thicker look than Ionic columns, which have 8:1 proportions. It is suggested that these proportions give the Doric columns a masculine appearance, whereas the more slender Ionic columns appear to represent a more feminine look. This sense of masculinity and femininity was often used to determine which type of column would be used for a particular structure.

Later periods reviving classical architecture used the Roman Doric until Neoclassical architecture arrived in the later 18th century. This followed the first good illustrations and measured descriptions of Greek Doric buildings. The most influential, and perhaps the earliest, use of the Doric in Renaissance architecture was in the circular Tempietto by Donato Bramante (1502 or later), in the courtyard of San Pietro in Montorio, Rome.[12]

Graphics of ancient forms

edit-

Original Doric polychromy

-

Upper parts, labelled

-

Three Greek Doric columns

-

The Five Orders, originally illustrated by Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola, 1640

Modern

editBefore Greek Revival architecture grew, initially in England, in the 18th century, the Greek or elaborated Roman Doric order had not been very widely used, though "Tuscan" types of round capitals were always popular, especially in less formal buildings. It was sometimes used in military contexts, for example the Royal Hospital Chelsea (1682 onwards, by Christopher Wren). The first engraved illustrations of the Greek Doric order dated to the mid-18th century. Its appearance in the new phase of Classicism brought with it new connotations of high-minded primitive simplicity, seriousness of purpose, noble sobriety.

In Germany it suggested a contrast with the French, and in the United States republican virtues. In a customs house, Greek Doric suggested incorruptibility; in a Protestant church a Greek Doric porch promised a return to an untainted early church; it was equally appropriate for a library, a bank or a trustworthy public utility. The revived Doric did not return to Sicily until 1789, when a French architect researching the ancient Greek temples designed an entrance to the Botanical Gardens in Palermo.

Examples

edit- Ancient Greek, Archaic

- Temple of Artemis, Corfu, the earliest known stone Doric temple

- Temple of Hera, Olympia

- Delphi, temple of Apollo

- The three temples at Paestum, Italy

- Valle dei Templi, Agrigento, Temple of Juno, Agrigento and others

- Temple of Aphaea

- Ancient Greek, Classical

- Temple of Zeus, Olympia

- Temple of Hephaestus

- Bassae, Temple of Apollo

- Parthenon, Athens

- Sounion, Temple of Poseidon

- Renaissance and Baroque

- The Tempietto by Donato Bramante, in the courtyard of San Pietro in Montorio, Rome

- Palace of Charles V, Granada, 1527, circular arcade in the courtyard, under Ionic in the upper storey

- Basilica Palladiana, in Vicenza, Andrea Palladio, 1546 on, arcade under Ionic above

- Valladolid Cathedral, Juan de Herrera, begun 1589

- Neoclassical and Greek Revival

- Brandenburg Gate, Berlin, 1788

- The Grange, Northington, 1804

- Lord Hill's Column, Shrewsbury, England, 1814, 133 feet 6 inches (40.69 m) high

- Neue Wache, Berlin, 1816

- Royal High School, Edinburgh, completed 1829

- Walhalla, Regensburg, Bavaria, 1842

- Propylaea, Munich, 1854

- United States

- Second Bank of the United States, Philadelphia, 1824

- Naval Medical Center Portsmouth, 1827, pedimented temple front with ten columns

- Perry's Victory and International Peace Memorial in Put-in-Bay, Ohio, is the world's tallest and most massive Doric column at 352 feet (107 m).

- Harding Tomb in Marion, Ohio, is a circular Greek temple design with Doric columns.

Gallery

edit-

Possible inspiration for the Doric order: Ancient Egyptian columns of the shrine of Anubis at the Temple of Hatshepsut, Deir el-Bahari, Egypt, c.1470 BC[13]

-

19th century illustration of the main façade of the Ancient Greek Temple T at Selinunte, Sicily, Italy, showing how all the ancient Doric buildings were polychromatic, by Jacques Ignace Hittorff, before 1859

-

Illustration of a peristyle with Doric columns the home of a rich Athenian woman, showing the polychromy Doric columns had in antiquity, from Wonders - Images of the Ancient World, 1907

-

Ancient Greek Doric capital of the Temple of Hera I, Paestum, Italy, with a band of compressed leafs just under the echine, 425 BC

-

Ancient Greek Doric columns of the Temple of Hera I, with their usually large entasis on the shafts

-

Ancient Greek Doric columns of the Temple of the Delians, Delos, Greece, fluted only at the top and bottom of the shaft, 5th century BC

-

Ancient Greek Doric temple depicted stylized on an amphora shard, c.400-385 BC, ceramic, Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

-

Ancient Greek Doric columns of the Tholos of Delphi, Greece, c.375 BC[17]

-

Ancient Greek Doric columns of the Temple of Zeus, Nemea, Greece, c.330 BC

-

Ancient Greek Doric pilasters and entablature of the Tomb III, Agios Athanasios, Greece, 325-300 BC

-

Roman Doric frieze on the Sarcophagus of Lucius Cornelius Scipio Barbatus, Vatican Museums, Rome, c.270 BC

-

Roman Doric order of the Theatre of Marcellus, Rome, 1st century BC

-

Renaissance Doric columns and entablature of The Tempietto, San Pietro in Montorio, Rome, by Donato Bramante, 1502[19]

-

Renaissance Doric altar enframement, probably from Tuscany, Italy, c.1530–1550, marble, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

-

Renaissance Doric columns and entablature of the entrance gateway of the Château d'Anet, near Dreux, France, by Philibert de l'Orme, 1547–1552[20]

-

Renaissance Doric capital at Hôtel d'Assézat designed according to a model published by Sebastiano Serlio, France, 1555–1556

-

Renaissance combination of Doric pilasters and corbels of the Château du Pailly, Le Pailly, France, 1563–1573

-

Baroque columns and entablature of the Château de Maisons, France, by François Mansart, 1630–1651[21]

-

Baroque Doric pilasters and entablature on the facade of the Hôtel de Castries (Rue Saint-Guilhem no. 31), Montpellier, France, by Simon Levesville, 1647[22]

-

Chinoiserie reinterpretation of the Doric frieze on a fireplace in the oval room inside the Oratorio dei Filippini, Rome, by Francesco Borromini, 1637–1650

-

Rococo Doric columns and pilasters on the facade of the abbey church of Ottobeuren, Germany, by Johann Michael Fischer, 1748–1754[23]

-

Neoclassical columns and entablature of the Casino at the Marino House, near Dublin, Ireland, by William Chambers, 1758–1776[24]

-

Neoclassical Doric frieze with circular motifs in the metopes that alternate with mascarons, in the Marble Saloon of the Stowe House, Stowe, Buckinghamshire, UK, probably by Vincenzo Valdrè, 1775–1788

-

Greek Revival columns of the Johannes Kepler Monuments, Regensburg, Germany, inspired by those of the Temple of the Delians in Delos, designed by Emanuel Herigoyen and sculpted by Philipp Jakob Scheffauer and Johann Heinrich Dannecker, 1808

-

Greek Revival columns of the Neue Wache, Berlin, where the triglyphs were replaced by Nike figures, by Karl Friedrich Schinkel and Salomo Sachs, 1816[25]

-

Neoclassical Doric pilasters with arches on the entrance front façade of the Sainte-Geneviève Library, Paris, designed by Henri Labrouste in 1838–1839, built in 1834–1850[26]

-

Neoclassical Doric pilasters on the Grave of Casimir Pierre Perier, Père-Lachaise Cemetery, Paris, designed by Achille Leclère, and sculpted by François-Joseph Bosio and Jean-Pierre Cortot, 1837

-

Beaux Arts Doric pilasters in the avant-foyer of the Palais Garnier, Paris, by Charles Garnier, 1861–1874[27]

-

Renaissance Revival Doric pilasters with bossages on them, of the Deutsche Bank (Mauerstraße no. 29), Berlin, by W. Martens, 1882

-

Eclectic façade with triglyphs and metopes of the Suriname Embassy (Rue du Ranelagh no. 94), Paris, unknown architect, 1885

-

Vienna Secession Doric columns on the frame of Die Sünde, painted by Franz Stuck, 1893, gilt wood and oil on canvas

-

Greek Revival columns at the entrance of the House of the New York City Bar Association, New York City, inspired by the one from the Temple of Hera I at Paestum, but decorated with meanders on the abacuses and bands of compressed leafs that are a little more complex and bases you would never see on Ancient Greek Doric columns (not visible in this photo), by Cyrus Eidlitz, 1895

-

Beaux Arts Doric pilasters on the façade of the Gare d'Orsay, Paris, designed by Victor Laloux in c.1896–1897, and built in 1898–1900[28]

-

Vienna Secession Doric columns on a dresser, by Leopold Bauer, 1900–1902, various types of wood, in a temporary exhibition called Il Liberty e la rivoluzione europea delle arti at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague

-

Art Nouveau Doric columns and entablature of The Greek Theatre in the Park Güell, Barcelona, Spain, by Antoni Gaudí, 1900–1914[29]

-

Beaux Arts Doric pilasters of the Pont de Bir-Hakeim, Paris, by Jean Camille Formigé and Louis Biette, 1903–1905

-

Art Deco reinterpretation of the Doric pilasters on the facade of Avenue du Président-Wilson no. 18, Paris, by Henri Tauzin, 1913[30]

-

Art Deco reinterpretation of the Doric columns, with no flutings and with little or no entasis, on the Westmorland House (Regent Street no. 117–131), London, by Burnet & Tait, 1920-1925[31]

-

Art Deco reinterpretation of the Doric columns, with no capitals or bases, on the Gustave Simon Grave, Préville Cemetery, Nancy, France, unknown architect, after 1926

-

Neoclassical and Art Deco Doric columns of the Vasile I. Prodanof family tomb, Bellu Cemetery, Bucharest, unknown architect, c. 1930

-

Postmodern reinterpretation of the Doric columns in the Harold Washington Library, Chicago, by Hammond, Beeby & Babka, 1991[33]

-

Postmodern Doric columns of the Judge Business School, University of Cambridge, England, by John Outram, 1995[34]

-

Postmodern Doric pilasters and columns of the Duncan Hall, Rice University, US, by John Outram, 1996[35]

-

New Classical Doric columns of the Queen's Gallery, Buckingham Palace, London, inspired by the one from the Temple of Hera I at Paestum, by John Simpson, 2000-2002[36]

-

New Classical Doric columns of the Federal Building and Courthouse, Tuscaloosa, Alabama, US, inspired by those of the Temple of Zeus in Nemea, by the Chicago architectural firm Hammond Beeby Rupert Ainge, 2011

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Art a Brief History 6th Edition

- ^ Summerson, 13–14

- ^ Vitruvius. De architectura. p. 4.1. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ Summerson, 14–15

- ^ Palladio, First Book, Chapter 12

- ^ Summerson, 13–15, 126

- ^ Ian Jenkins, Greek Architecture And Its Sculpture (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2006), 15.

- ^ Jenkins, 16.

- ^ Jenkins, 16–17.

- ^ Robin F. Rhodes, "Early Corinthian Architecture and the Origins of the Doric Order" in the American Journal of Archaeology 91, no. 3 (1987), 478.

- ^ "... they measured a man's foot, and finding its length the sixth part of his height, they gave the column a similar proportion, that is, they made its height, including the capital, six times the thickness of the shaft, measured at the base. Thus the Doric order obtained its proportion, its strength, and its beauty, from the human figure." (Vitruvius, iv.6) "The successors of these people, improving in taste, and preferring a more slender proportion, assigned seven diameters to the height of the Doric column." (Vitruvius, iv.8)

- ^ Summerson, 41–43

- ^ Watkin, David (2022). A History of Western Architecture. Laurence King. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

- ^ Watkin, David (2022). A History of Western Architecture. Laurence King. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

- ^ Watkin, David (2022). A History of Western Architecture. Laurence King. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

- ^ Watkin, David (2022). A History of Western Architecture. Laurence King. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

- ^ Watkin, David (2022). A History of Western Architecture. Laurence King. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

- ^ Fullerton, Mark D. (2020). Art & Archaeology of The Roman World. Thames & Hudson. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-500-051931.

- ^ Watkin, David (2022). A History of Western Architecture. Laurence King. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

- ^ Watkin, David (2022). A History of Western Architecture. Laurence King. ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

- ^ Hopkins 2014, p. 85.

- ^ "Ancien Hôtel de Castries à Montpellier". monumentum.fr. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- ^ Watkin, David (2022). A History of Western Architecture. Laurence King. p. 333. ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

- ^ Watkin, David (2022). A History of Western Architecture. Laurence King. p. 383. ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

- ^ Hall, William (2019). Stone. Phaidon. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-7148-7925-3.

- ^ Watkin, David (2022). A History of Western Architecture. Laurence King. p. 447. ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

- ^ Robertson, Hutton (2022). The History of Art - From Prehistory to Presentday - A Global View. Thames & Hudson. p. 989. ISBN 978-0-500-02236-8.

- ^ Watkin, David (2022). A History of Western Architecture. Laurence King. p. 457. ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

- ^ Watkin, David (2022). A History of Western Architecture. Laurence King. p. 560. ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

- ^ Les Arts Decoratifs Modernes - France (in French). Larousse. 1925. p. 17.

- ^ "History Above Your Eyeline on Regent Street". lookup.london. 23 June 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2024.

- ^ Hall, William (2019). Stone. Phaidon. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-7148-7925-3.

- ^ Gura, Judith (2017). Postmodern Design Complete. Thames & Hudson. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-500-51914-1.

- ^ Gura, Judith (2017). Postmodern Design Complete. Thames & Hudson. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-500-51914-1.

- ^ Lizzie Crook (February 14, 2020). "Less is a Bore book celebrates "postmodern architecture in all its forms"". dezeen.com. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ Watkin, David (2022). A History of Western Architecture. Laurence King. p. 673. ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

References

edit- Summerson, John, The Classical Language of Architecture, 1980 edition, Thames and Hudson World of Art series, ISBN 0500201773

- James Stevens Curl, Classical Architecture: An Introduction to Its Vocabulary and Essentials, with a Select Glossary of Terms

- Georges Gromort, The Elements of Classical Architecture

- Hopkins, Owen (2014). Architectural Styles: A Visual Guide. Laurence King. ISBN 978-178067-163-5.

- Lawrence, A. W., Greek Architecture, 1957, Penguin, Pelican history of art

- Alexander Tzonis, Classical Architecture: The Poetics of Order (Alexander Tzonis website)

- Zuchtriegel, Gabriel (2023). The Making of the Doric Temple: Architecture, Religion, and Social Change in Archaic Greece. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781009260107. google books

- Watkin, David, A History of Western Architecture, 1986, Barrie & Jenkins, ISBN 0712612793

- Yarwood, Doreen, The Architecture of Europe, 1987 (first edn. 1974), Spring Books, ISBN 0600554309

External links

editMedia related to Doric columns at Wikimedia Commons