Ronald Shannon Jackson (January 12, 1940 – October 19, 2013) was an American jazz drummer from Fort Worth, Texas.[1] A pioneer of avant-garde jazz, free funk, and jazz fusion, he appeared on over 50 albums as a bandleader, sideman, arranger, and producer. Jackson and bassist Sirone are the only musicians to have performed and recorded with the three prime shapers of free jazz: pianist Cecil Taylor, and saxophonists Ornette Coleman and Albert Ayler.[2]

Ronald Shannon Jackson | |

|---|---|

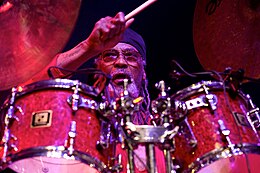

Jackson at the 2011 Moers Festival | |

| Background information | |

| Born | January 12, 1940 Fort Worth, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | October 19, 2013 (aged 73) Fort Worth, Texas, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupation | Percussionist |

| Years active | 1958–2013 |

| Labels | Antilles, DIW, Moers |

| Formerly of | The Decoding Society, Last Exit |

| Website | ronaldshannonjackson |

Musician, Player and Listener magazine writers David Breskin and Rafi Zabor called him "the most stately free-jazz drummer in the history of the idiom, a regal and thundering presence."[3] Gary Giddins wrote "Jackson is an astounding drummer, as everyone agrees...he has emerged as a kind of all-purpose new-music connoisseur who brings a profound and unshakably individual approach to every playing situation."[4]

In 1979, he founded his own group, the Decoding Society,[1] playing what has been dubbed free funk: a blend of funk rhythm and free jazz improvisation.

Early life and career

editJackson was born in Fort Worth, Texas.[1] As a child, he was immersed in music. His father monopolized the local jukebox business and established the only African American-owned record store in the Fort Worth area. His mother played piano and organ at their local church. Between the ages of five and nine he took piano lessons.[5] In the third grade, he studied music with John Carter.[6]

Jackson graduated from I.M. Terrell High School,[7][8] where he played with the marching band and learned about symphonic percussion.[9][10] During lunch breaks, students would conduct jam sessions in the band room.[5]

Around the same time, Jackson's mother bought him his first drum set to encourage him to graduate from high school. By the age of 15, he was playing professionally. His first paid gig was with tenor saxophonist James Clay, who went on to join Ray Charles as a sideman.[5]

Jackson recalled that "we were playing four nights a week, with two gigs each on Saturday and Sunday, anything from Ray Charles to bebop. People were dancing, and when it was time to listen, they'd listen. But I was brainwashed into thinking you couldn't make a living playing music."[5]

After graduation, Jackson attended Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Missouri. He chose Lincoln because of its proximity to St. Louis and accessibility to great musicians touring the Midwest. His roommate was pianist John Hicks. As undergraduates, they "spent as much time performing together as studying."[11] The Lincoln University band included Jackson, Hicks, trumpeter Lester Bowie, and Julius Hemphill on saxophone.[12]

Jackson then transferred to Texas Southern University, and from there went to Prairie View A & M. He decided to study history and sociology at the University of Bridgeport in Connecticut. Jackson intended not to play music at all, but after exposure to various artists and styles, he concluded that "the beat is in your body" and "the music you play comes from your life."[13] By 1966, Jackson received a full music scholarship to New York University through trumpeter Kenny Dorham.[14]

New York and the Avant-Garde (1966–1978)

editOnce in New York, Jackson performed with many jazz musicians, including Charles Mingus, Betty Carter, Jackie McLean, Joe Henderson, Kenny Dorham, McCoy Tyner, Stanley Turrentine, and others.[15] Whenever he would ask Charles Mingus to consider him for his group, Mingus used to push him "rudely out of his way". After Jackson sat in with pianist Toshiko Akiyoshi, he heard loud clapping behind him. It was Mingus, who asked him to play with his band.[16]

In 1966 Jackson recorded drums for saxophonist Charles Tyler's release, Charles Tyler Ensemble. Between 1966 and 1967, he played with saxophonist Albert Ayler and is featured on At Slug's Saloon, Vol. 1 & 2. He is also on disks 3 and 4 of Ayler's Holy Ghost: Rare & Unissued Recordings (1962–70). Jackson said Ayler was "the first (leader) that really opened me up. He let me play the drums the way I did in Fort Worth when I wasn't playing for other people."[5] John Coltrane's death in July 1967 devastated Jackson. He spent the next few years addicted to heroin. He said, "I couldn't play drums then, spiritually.... I just didn't feel right."[5] From 1970–74, he did not perform, but continued to practice.[15]

In 1974, pianist Onaje Allan Gumbs introduced Jackson to Nichiren Buddhism and chanting. Although initially reluctant, Jackson decided to try it for three weeks. "Then three months had passed. It pulled me together and pulled me out and I was able to focus. I was a Buddhist and a vegetarian for 17 years."[5]

By 1975 he joined saxophonist Ornette Coleman's electric free funk band, Prime Time.[15] During his stint in Prime Time, Coleman taught Jackson composition and harmolodics. Jackson says that Coleman told him he was hearing music "in that piccolo range," and encouraged him to compose on the flute. Jackson went to Paris with Prime Time in 1976 to perform concerts and record Dancing in Your Head and Body Meta.[5]

In 1978, Jackson played on four albums with pianist Cecil Taylor: Cecil Taylor Unit, 3 Phasis, Live in the Black Forest, and One Too Many Salty Swift and Not Goodbye.[17]

The Decoding Society and Other Projects (1979–1999)

editJackson formed his band, The Decoding Society, in 1979, as a showcase for his blend of avant-garde jazz, rock, funk, and ethnic music. The instrumentation and arrangements, along with Jackson's compositions and drum style, brought The Decoding Society critical acclaim.[18] Although considered to be part of the "new fusion" movement that emerged from Ornette Coleman's harmolodic concepts, Jackson was able to implement a voice of his own.[19]

The Decoding Society's music can be hot, savage, and danceable, or cool, gentle, and contemplative. American, Eastern, and African sounds are distilled under Jackson's guidance. Meters, feels, tempos, and stylistic references are heard throughout different compositions; many times within a single piece of music.[19]

Unlike many of Jackson's contemporaries, The Decoding Society incorporates pop music elements into its avant-garde approach. Guitarist Vernon Reid has said of Shannon that he "wasn't an ideological avant-gardist. He made the music he made from an outsider's view, but not to the exclusion of rock and pop – he wasn't mad at pop music for being popular the way some of his generation are. He synthesized blues shuffles with African syncopations through the lens of someone who gave vent to all manner of emotions...the collision of values in his music really represents American culture."[5]

Common characteristics among the incarnations of The Decoding Society include doubled instrumentation (basses, saxophones, or guitars). Polyphony often predominates harmony; compositions are not focused on one key. Polyphonic textures equalize harmony, rhythm, and melody, dispensing with traditional ideas of key and pitch. Each instrument can play a rhythmic, harmonic, or melodic role, or any combination of the three. The lines between solos, lead instruments, and accompaniment are blurred. Looseness in pitch and rhythm create heterophony within unison-based parts, which also adds to the tonal ambiguity.[19]

Melodies can alternate from busy, frenetic, multiple themes to simple, lazy, lyrical phrases. They often function as both heads and melodic material to accompany one or more soloist. Sometimes the melodies are diatonic, other times they are bluesy; occasionally they sound "Eastern". Although The Decoding Society is more of a composer's band rather than a vehicle for soloing or drumming, free-blowing solos abound, and Jackson's thunderous playing is heavily featured.[19]

Throughout the years, the Decoding Society has featured the performances of Akbar Ali, Bern Nix, Billy Bang, Byrad Lancaster, Cary Denigris, Charles Brackeen, David Fiuczynski, David Gordon, Tomchess, Dominic Richards, Eric Person, Henry Scott, Jef Lee Johnson, John Moody, Khan Jamal, Lee Rozie, Masujaa, Melvin Gibbs, Onaje Allan Gumbs, Reggie Washington, Reverend Bruce Johnson, Robin Eubanks, Vernon Reid, and Zane Massey.[20]

In addition to leading Decoding Society lineups, Jackson was involved in other projects. Guitarist and fellow Coleman alumnus James Blood Ulmer recruited Jackson for another group that intended to push harmolodics to a new level [18]

In 1986 Jackson, Sonny Sharrock, Peter Brötzmann, and Bill Laswell formed the free jazz supergroup, Last Exit, which performed and released five live albums and one studio album, before Sharrock's death in 1994 saw the end of the band.[21]

In the late 1980s, Jackson teamed up with Laswell on two other projects: SXL, with violinist L. Shankar, Senegalese drummer Aiyb Dieng, and Korean percussion group SamulNori,[22] and the free jazz trio, Mooko, with Japanese saxophonist Akira Sakata.[23]

With the help of some grants, Jackson took a three-month trip to West Africa and visited nine countries.[5] The trip, both a personal and artistic milestone, inspired music for the Decoding Society's When Colors Play, recorded live at the Caravan of Dreams in September 1986.[19] Author Norman C. Weinstein detailed the excursion in a chapter of his book, A Night in Tunisia: Imaginings of Africa in Jazz, titled "Ronald Shannon Jackson: Journey to Africa Without End."[24]

In 1987, Jackson formed an avant-garde power trio with bassist Melvin Gibbs and guitarist Bill Frisell called Power Tools. They released and toured behind an album titled Strange Meeting.[25] Writer Greg Tate referred to the project as "that awesome and under-sung Power Tools album...in my humble opinion, the most paradigm-shifting power trio record since Band of Gypsys."[26]

Later career (2000–2013)

editHis output slowed in the early 2000s due to nerve damage in his left arm. After consulting with a neurologist, Jackson declined surgery and was able to regain his strength through years of physical therapy. Physical limitations did not diminish his output as a composer, and he unveiled new material on YouTube in 2012.[27]

Jackson joined trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith's Golden Quartet with pianist Vijay Iyer and double-bassist John Lindberg in 2005. Their collaboration is documented on the Tabligh CD[28] and the Eclipse DVD.[29]

He played with the Punk Funk All Stars in 2006, which included Melvin Gibbs, Joseph Bowie, Vernon Reid, and James Blood Ulmer.[30] In 2008 Jackson and Jamaaladeen Tacuma toured Europe with The Last Poets; this collaboration was documented in the film "The Last Poets / Made in Amerikkka" directed by Claude Santiago.[31]

In 2011 Jackson, Vernon Reid and Melvin Gibbs formed a power trio called Encryption. During their trip to the Moers Festival in Germany, Jackson suffered a heart attack and underwent an angioplasty.[32] The next day, he checked himself out of the hospital to play with Reid and Gibbs at the festival. Afterwards, Jackson checked himself back in for medical observation.[33]

On July 7, 2012, Jackson performed at the Kessler Theater in Dallas with the latest version of the Decoding Society, which includes violinist Leonard Hayward, trumpeter John Weir, guitarist Gregg Prickett, and bassist Melvin Gibbs. The new compositions were described as being as strong as the best of his recorded work.[34] The performance was voted as one of the Ten Best Concerts of 2012 in the Dallas Observer.[35]

Death

editJackson died of leukemia on October 19, 2013, aged 73.[36]

Discography

editAs leader

edit- Eye on You (About Time, 1980)

- Nasty (Moers Music, 1981)

- Street Priest (Moers, 1981)

- Mandance (Antilles, 1982)

- Barbeque Dog (Antilles, 1983)

- Montreux Jazz Festival (Knit Classics, 1983)

- Pulse (Celluloid, 1984)

- Decode Yourself (Island, 1985)

- Earned Dream (Knit Classics, 1984)

- Live at Greenwich House (Knit Classics, 1986)

- Live at the Caravan of Dreams (Caravan of Dreams, 1986) AKA Beast in the Spider Bush

- When Colors Play (Caravan of Dreams, 1986)

- Texas (Caravan of Dreams, 1987)

- Red Warrior (Axiom, 1990)

- Taboo (Venture/Virgin, 1990)

- Raven Roc (DIW, 1992)

- Live in Warsaw (Knit Classics, 1994)

- What Spirit Say (DIW, 1994)

- Shannon's House (Koch, 1996)

(dates are recording, not release)

With Last Exit

- Last Exit (Enemy, 1986)

- The Noise of Trouble (Enemy, 1986) with guests Akira Sakata and Herbie Hancock

- Cassette Recordings '87 (Celluloid, 1987)

- Iron Path (Virgin, 1988)

- Köln (ITM, 1990)

- Headfirst into the Flames (Muworks, 1993)

As sideman

edit|

With Albert Ayler

With Ornette Coleman

With Music Revelation Ensemble

With SXL

With Cecil Taylor

With James Blood Ulmer

|

with others

|

References

edit- ^ a b c Yanow, Scott. Ronald Shannon Jackson at AllMusic

- ^ Jackson and Sirone are cited as having recorded with these artists in discographies of Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, and Albert Ayler.

- ^ Zabor, Rafi; David Breskin (June 1981). "Ronald Shannon Jackson: The Future of Jazz Drumming". Musician, Player and Listener: 64.

- ^ Giddins, Gary (2004): Weather Bird: Jazz at the Dawn of Its Second Century. Oxford; Oxford University Press, p. 14; ISBN 0195156072

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Shimamoto, Ken (January 2, 2003). "Legend Shadows". Fort Worth Weekly.

- ^ Oliphant, Dave (1996): Texan Jazz. Austin; University of Texas Press, p. 336; ISBN 0292760450

- ^ Collier, Caroline (February 27, 2008). "Jazz jumps back onto the Cowtown scene". Fort Worth Weekly. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- ^ Patoski, Joe Nick (2008). Willie Nelson: An Epic Life. Little, Brown. p. 50. ISBN 9780316017787. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- ^ Ken Shimamoto, Legend Shadows, January 2, 2003.

- ^ "Fort Worth Flashback: I.M. Terrell music program produced jazz greats". Fort Worth City News. November 20, 2012.

- ^ Berliner, Paul F. (1994): "Thinking in Jazz: The Infinite Art of Improvisation". Chicago; University of Chicago Press, pp. 56-57; ISBN 0226043819

- ^ Ian Carr, Brian Priestley, and Digby Fairweather (2004): "The Rough Guide to Jazz", New York/London; Rough Guides, page 360, ISBN 1843532565

- ^ Oliphant, Dave (1996): Texan Jazz. Austin; University of Texas Press, pages 336-37, ISBN 0292760450

- ^ Jung, Fred (March 31, 1999). "Fireside Chat With: Ronald Shannon Jackson". Jazz Weekly.

- ^ a b c Feather, Leonard; Gitler, Ira (1999): "The Biographical Encyclopedia of Jazz". New York; Oxford University Press, page 347, ISBN 019532000X

- ^ Berliner, Paul F. (1994): "Thinking in Jazz: The Infinite Art of Improvisation". Chicago; University of Chicago Press, pp. 52-53; ISBN 0226043819

- ^ Cecil Taylor at AllMusic

- ^ a b Jenkins, Todd S. (2004): "Free Jazz and Free Improvisation: An Encyclopedia, Volume 2". Westport, Connecticut; Greenwood Press, p. 188; ISBN 0313298815

- ^ a b c d e Eldredge, Jeff (Spring 2001). "Knitting Factory Reissue Series of Ronald Shannon Jackson and the Decoding Society". Echo: A Music-Centered Journal. 3 (1).

- ^ Ronald Shannon Jackson discography at Discogs

- ^ Last Exit details, AllMusic.com; accessed March 3, 2016.

- ^ Into the Outlands – Bill Laswell details, AllMusic.com; accessed March 3, 2016.

- ^ Mooko profile, AllMusic.com; accessed March 3, 2016.

- ^ Weinstein, Norman (1992): A Night in Tunisia" Imaginings of Africa in Jazz. Metuchen, New Jersey; Scarecrow Press, pp. 166-175;ISBN 0879101679

- ^ Ronald Shannon Jackson And The Decoding Society details, Discogs.com; accessed March 3, 2016.

- ^ Greg Tate, "Burning Ambulance 5: Winter 2011", December 12, 2011.

- ^ Preston Jones, "Fort Worth's Ronald Shannon Jackson Doesn't Miss a Beat", dfw.com, July 3, 2012.

- ^ "Wadada Leo Smith's Golden Quartet: Tabligh (2008)" by Kurt Gottschalk, All About Jazz, July 19, 2008.

- ^ Profile, worldcat.org; accessed March 3, 2016.

- ^ "Bohemia Jazz Fest 2006" by Bill Milkowski, JazzTimes, July 17, 2006

- ^ "The Last Poets / Made in Amerikkka". La Huit Production. Archived from the original on October 24, 2011.

- ^ "Fort Worth's Ronald Shannon Jackson doesn't miss a beat" by Preston Jones, dfw.com, July 3, 2012

- ^ Ken Waxman, "Festival Report: Moers Festival June 10 to 12, 2011", Jazzword.com; accessed March 3, 2016.

- ^ Ken Shimamoto, "Ronald Shannon Jackson – The Kessler Theater – 7/7/12". The Dallas Observer, Monday, July 9, 2012

- ^ Audra Shroeder "Ten of the Best Concerts of 2012", The Dallas Observer, December 11, 2012.

- ^ Tamarkin, Jeff. "Drummer & Composer Ronald Shannon Jackson Dies at 73". JazzTimes.

Further reading

edit- Blumenthal, Bob (November 16, 1982). "Decoding jazz: Ronald Shannon Jackson's high society". The Boston Phoenix. Retrieved October 2, 2024.