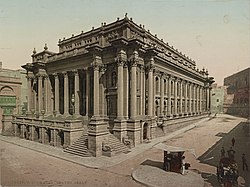

The Royal Opera House, also known as the Royal Theatre (Maltese: It-Teatru Rjal, Italian: Teatro Reale), was an opera house and performing arts venue in Valletta, Malta. It was designed by the English architect Edward Middleton Barry and was erected in 1866. In 1873 its interior was extensively damaged by fire but was eventually restored by 1877. The theatre received a direct hit from aerial bombing in 1942 during World War II. Prior to its destruction, it was one of the most beautiful and iconic buildings in Valletta.[1] After several abandoned plans to rebuild the theatre, the ruins were redesigned by the Italian architect Renzo Piano and in 2013 it once again started functioning as a performance venue, called Pjazza Teatru Rjal.[2]

Royal Opera House in 1911 | |

| |

| Address | Republic Street Valletta Malta |

|---|---|

| Type | Opera House |

| Capacity | 1295 |

| Construction | |

| Opened | 1866 |

| Rebuilt | Reopened as open-air theatre in 2013 |

| Years active | 1866–1873 1877–1942 |

| Architect | Edward Middleton Barry |

History

editThe design of the building was entrusted to Edward Middleton Barry, the architect of Covent Garden Theatre, and the classic design plan was completed by 1861.[3][4][5] The original plans had to be altered because the sloping streets on the sides of the theatre had not been taken into consideration. This resulted in a terrace being added on the side of Strada Reale (nowadays Republic Street) designed by Maltese architects.[6]

The building of the 206 feet (63 m) by 112 feet (34 m) site[citation needed] started in 1862, after what was the Casa della Giornata was demolished. After four years, the Opera House, with a seating capacity of 1,095 and 200 standing, was ready for the official opening on 9 October 1866.[7]

The theatre was not to last long; on 25 May 1873,[8] a mere six years after its opening, it was brought to a premature end by a fire.[9] The exterior of the theatre was undamaged but the interior stonework was calcified by the intense heat.

It was decided to rebuild the theatre, and after the issuing of tenders for the work and a lot of arguing whether the front had to be changed or not, the theatre was ready. On 11 October 1877, nearly four and a half years after the fire, the theatre reopened with a performance of Verdi's Aida.

Some 65 years later, tragedy struck the Royal Opera House again:

On the evening of Tuesday, April 7, 1942, the theatre was devastated by Luftwaffe bombers. The next morning a people hardened by aerial bombing inspected the remains of their national theatre.... The portico and the auditorium were a heap of stones, the roof a gaping hole of twisted girders. The rear end starting half way from the colonnade was however intact.[10]

The remaining structures were razed in the late 1950s as a safety precaution. There is a claim that German prisoners-of-war in Malta offered to rebuild the theatre in 1946 with the Government declining due to Union pressure; the more likely reason might be that few of these prisoners of war could be expected to be qualified masons.[citation needed]

All that remained of the Opera House were the terrace and parts of the columns.

Site ruins and reconstruction plans

editAlthough the bombed site was cleared of much of the rubble and all of the remaining decorative sculpture, rebuilding was repeatedly postponed by successive post-War governments, in favour of reconstruction projects that were deemed to be more pressing.

In 1953 six renowned architects submitted designs for the new theatre. The Committee chose Zavellani-Rossi's project and recommended its acceptance by Government subject to certain alterations. The project ground to a halt on Labour's re-election, contending that it was not in a position to spend so much money on a theatre when so many other projects needed attention. Although a provision of £280,000 for the reconstruction of the theatre had been made in the 1955-56 budget, these were never used. By 1957 the project had been shelved and after 1961 all references to the theatre in the country's development plans were omitted.

In the 1980s contact was made with the architect Renzo Piano to design a building to be constructed on site and to rehabilitate the entrance of the city. Piano submitted the plans which were approved by the Government in 1990 but work never started. In 1996 the incoming Labour Government announced that reconstruction of the site into a commercial and cultural complex together with an underground car park would be Malta's millennium project. In the late 1990s the Maltese architect Richard England was also commissioned to come up with plans for a cultural centre. Each time, controversies killed off all initiatives.

Pjazza Teatru Rjal

edit| Pjazza Teatru Rjal, illuminated at night | |

| Address | Republic Street Valletta Malta |

|---|---|

| Type | Theatre |

| Construction | |

| Opened | 2013 |

| Years active | 2013–present |

| Architect | Renzo Piano |

| Website | |

| pjazzateatrurjal.mt | |

In 2006 the government announced a proposal to redevelop the site for a dedicated House of Parliament, which by then was located in the former Armoury of the Grandmaster's Palace in Valletta. The proposal was not well received since it had always been assumed that the site would eventually be developed into something that would house a cultural institution; however, Renzo Piano was again approached and started to work on new designs. The proposal was ostensibly shelved until after the general elections of 2008 and, on 1 December 2008, Prime Minister Lawrence Gonzi revived the proposal with a budget of €80 million. Piano dissuaded the Government from building a Parliament on site of the Opera House, instead planning a House of Parliament on present-day Freedom Square and a re-modelling of the city gate. Piano proposed an open-air theatre for the site.

The development of the theatre by Piano is the most controversial in its time.[11] The government still went ahead with the plans and the open-air theatre was officially inaugurated on 8 August 2013. The theatre was named Pjazza Teatru Rjal after the original structure.[12] The name translates to Royal Theatre Square, but the venue is always referred to by its Maltese name, even when written about in English.[13]

Further reading

edit- Badger, George Percy (1869). Historical Guide to Malta and Gozo. Calleja. pp. 218–219.

- Gauci, M. (2009). "New Light On Webster Paulson and his Architectural Idiosyncrasies" (PDF). Proceedings of History Week (PHW). 12 (9): 137–150. ISBN 978-99932-7-400-1.

References

edit- ^ "Valletta's Royal Opera House, from glamour to rubble". The Man Who Went To Malta. 12 December 2011. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014.

- ^ "Pjazza Teatru Rjal". Malta Ministry of Culture. Archived from the original on April 10, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ Borg, Malcolm (2001). British Colonial Architecture: Malta, 1800-1900. Publishers Enterprises Group. p. 138. ISBN 978-9990903003.

- ^ Squires, Nick (8 May 2010). "Maltese anger at plans to rebuild Valletta". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Rix, Juliet (2015). Malta and Gozo. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 118. ISBN 978-1784770259.

- ^ "Sir Adrian Dingli". Journal of the Maltese Historical Society. 1955. Archived from the original on 21 February 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Denaro, Victor F. (1959). Houses in Kingsway and Old Bakery Street, Valletta Archived 2015-11-17 at the Wayback Machine. Melita historica. Journal of the Malta Historical Society. 2 (4). p. 202.

- ^ Denaro, Victor F. (1959). Houses in Kingsway and Old Bakery Street, Valletta Archived 2015-11-17 at the Wayback Machine. Melita historica. Journal of the Malta Historical Society. 2 (4). p. 202.

- ^ Architect Andrea Vassallo Archived 2014-04-21 at the Wayback Machine. p. 228.

- ^ Bonnici, Joseph; Cassar, Michael (1990). The Royal Opera House – Malta. Gutenberg Press. p. 79.

- ^ Mallia, Nicholas. David Felice (ed.). "Chalet" (PDF). The Architect. Media Today: 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 January 2018.

- ^ "Valletta's open theatre officially inaugurated". Times of Malta. 8 August 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ Ameen, Juan (29 June 2013). "Pjazza Teatru Rjal to host arts festival". Times of Malta. Retrieved 15 April 2016.