Rufus Does Judy at Carnegie Hall is the sixth album (and first live album) by the Canadian-American singer-songwriter Rufus Wainwright, released through Geffen Records in December 2007. The album consists of live recordings from his sold-out June 14–15, 2006, tribute concerts at Carnegie Hall to the American actress and singer Judy Garland.[1] Backed by a 36-piece orchestra conducted by Stephen Oremus, Wainwright recreated Garland's April 23, 1961, concert, often considered "the greatest night in show business history".[2] Garland's 1961 double album, Judy at Carnegie Hall, a comeback performance with more than 25 American pop and jazz standards, was highly successful, initially spending 95 weeks on the Billboard charts and garnering five Grammy Awards (including Album of the Year, Best Album Cover, Best Solo Vocal Performance – Female and Best Engineering Contribution – Popular Recording).[3][4]

| Rufus Does Judy at Carnegie Hall | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Live album by | ||||

| Released | December 4, 2007 (US) | |||

| Recorded | June 14–15, 2006 | |||

| Venue | Stern Auditorium/Perelman Stage, Carnegie Hall, New York City | |||

| Label | Geffen | |||

| Producer | Phil Ramone | |||

| Rufus Wainwright chronology | ||||

| ||||

For his album, Wainwright was also recognized by the Grammy Awards, earning a 2009 nomination for Best Traditional Pop Vocal Album.[5] While the tribute concerts were popular and the album was well received by critics, album sales were limited. Rufus Does Judy at Carnegie Hall managed to chart in three nations, peaking at number 84 in Belgium, number 88 in the Netherlands and number 171 on the United States' Billboard 200.[6][7][8]

Guests on the album include Wainwright's sister Martha Wainwright ("Stormy Weather"), his mother Kate McGarrigle (piano, "Over the Rainbow"), along with one of Garland's daughters, Lorna Luft ("After You've Gone"). Related to the album, the February 25, 2007 tribute concert filmed at the London Palladium was released on DVD as Rufus! Rufus! Rufus! Does Judy! Judy! Judy!: Live from the London Palladium on December 4, 2007.

Conception and development

editAccording to Pitchfork, Wainwright "started listening to the Carnegie Hall album in the weeks and months after September 11, craving some cheap showbiz cheer, but wound up discovering something deeper".[9] The subsequent War on Terrorism and invasion of Iraq caused Wainwright to become "traumatized and disillusioned with anything American".[10] Claiming he was reminded of how great "the US used to be",[10] Wainwright said the following of his appreciation for the album during that turbulent time in American history:

Somehow that album, no matter how dark things seemed, made everything brighten. She had this capacity to lighten the world through the innocence of her sound. Her anchor to the material was obviously through her devotion to music. You never feel that she didn't believe every word of every song she ever sang.[11]

I find the political and socioeconomic environment we live in very oppressive and very worrying, but every time I put on that live album, I was immediately put in a better mood. I was given a sense of hope and a sense of escape, only because so much of modern-day culture and radio—and what's prized by our society—is so empty. And then of course I would sing along.[12]

Wainwright observed while driving in his car that "it [would] be funny to redo this as a song cycle".[10] Soon afterwards, he took the idea to New York-based theatrical producer Jared Geller (who would later co-produce the tribute concert with David Foster), hoping to turn a dream into a reality.[13] Geller initially thought the idea was "insane", but he and Wainwright continued discussing options. Eventually, Geller agreed to assist with the production and the two found space in Wainwright's schedule to book Carnegie Hall a year in advance.[13] Once the venue was booked, staging elements such as lighting, microphone location and amplification were discussed. Stephen Oremus signed on as the conductor of the 36-piece orchestra and Phil Ramone took charge of the recording.[14][15] Rehearsals began in April 2006, and while it would have been easier to practice in rehearsal rooms, large theaters such as the Lynch at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice and the Museum of Jewish Heritage were utilized because "Rufus wanted a feel for performing this material on a stage".[13] As a result of financial restrictions, full orchestra rehearsals took place only two days before the show and the day of each performance (practice with smaller groups of instruments began a few months before the concerts).[14]

Tribute concerts

editDue to popular demand, Wainwright's tribute was performed a total of six times. After tickets for the first show (June 14, 2006 at Carnegie Hall in New York City) sold out, a second show was added at the same venue for the following night (June 15). Increased demand resulted in three concerts in Europe: February 18, 2007 at the London Palladium in London, February 20 at L'Olympia in Paris and February 25 once again at the London Palladium.[16][17] The final performance was on September 23, 2007 at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles, California.[18]

Promotion, celebrity participation

editPart of the success of the tribute concerts can be attributed to the amount of press attention received and the eagerness of other artists to participate in the event. As written by Gaby Wood of The Guardian, Wainwright "sparkled on the cover of Time Out New York" and was "adored in the pages of The New York Times" following the Carnegie Hall shows.[19]

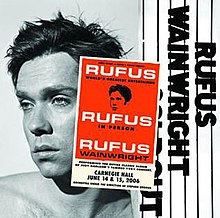

In fashion designer Marc Jacobs' menswear boutique in Greenwich Village, "virtually nothing was for sale except T-shirts advertising the show" (the bright orange shirts contained the text "RUFUS RUFUS RUFUS" and "world's greatest entertainer", mimicking promotional material used for Garland 45 years earlier).[19] Film director Sam Mendes planned to create a documentary about Wainwright's re-creation and the work leading up to it, though the project fell through.[20]

Dutch designers Viktor & Rolf outfitted Wainwright and his family members for the concerts.[21] To return the favor Wainwright wrote the song "Ode to Antidote" and allowed its use in the promotion of the design duo's cologne, "Antidote".[22] He also helped premiere the cologne at the after-party for his first Garland tribute and later performed "Over the Rainbow" at the premiere of their Spring 2007 fashion line.[23] Wainwright wore clothing by Tom Ford at the Hollywood Bowl concert.[24]

To promote the album, Wainwright's website linked to an online store where fans could purchase merchandise, including several shirt designs, concert posters, programs and other collectibles.[25][26] Like the shirts sold by Marc Jacobs, much of the promotional material mimicked posters used for Garland's concert years before.

Celebrities attending the Carnegie Hall shows included Justin Bond ("Kiki" of Kiki and Herb), Patricia Field, Gina Gershon, Joel Grey, Marc Jacobs, Michael Kors, Tony Kushner, Ann Magnuson, Sarah Jessica Parker, Kate Pierson, Fred Schneider, the Proenza Schouler boys, Chloë Sevigny, John Waters and Viktor & Rolf.[27][28] Famous faces turned out at the concerts in Europe as well, including Julian Barratt, Keane frontman Tom Chaplin, Julia Davis, David Furnish, Mark Gatiss, Richard E. Grant, Jeremy Irons, Lulu, Paul Morley, Siân Phillips, Imogen Stubbs and Teddy Thompson. Celebrities at the Hollywood Bowl show included Jamie Lee Curtis, Jimmy Fallon, Jake Gyllenhaal, Debbie Reynolds and Rod Stewart.[29]

Music

editSongs

editThe songs on the album are identical to those performed on Garland's 1961 album, Judy at Carnegie Hall, except Wainwright's album included "Get Happy" as a bonus track in the UK and on iTunes in the US.[30] "Hail[ing] from a golden era dotted with trolley cars, Cadillacs, and glitzy jazz clubs",[1] the set list included more than 25 American swing tunes, jazz and pop standards, including two Rodgers and Hart classics ("This Can't Be Love", "You're Nearer"), three from brothers George and Ira Gershwin ("Who Cares? (As Long as You Care for Me)", "How Long Has This Been Going On?" and "A Foggy Day"), two from duo Howard Dietz and Arthur Schwartz ("Alone Together", "That's Entertainment!"), Harold Arlen, Irving Berlin, Noël Coward and more. Wainwright performed the songs nearly identically to Garland, even "flubb[ing]" the lyrics purposely on "You Go to My Head" to mimic the mistake made by Garland years before.[9]

Orchestrations

editStephen Oremus, musical director for the tribute concerts, faced the task of resurrecting Mort Lindsey's original concert arrangements written for a 36-piece orchestra.[14] Although it is no longer common to have orchestras so large (Oremus acknowledged that even Wicked on Broadway only had 22 pieces), Wainwright and Oremus insisted the full 36-piece ensemble should be utilized to create "as exact a replica as [they could] muster".[14] Some of the well-known arrangements by orchestrators like Nelson Riddle and Conrad Salinger had to be reconstructed, since their music charts were not available, and most of the songs had to be transposed, since Wainwright was performing them in a different key.[14]

Gay elements

editGarland was a gay icon,[31] even before Wainwright was born. Gay identification with Garland was being discussed in the mainstream as early as 1967. Time magazine, in reviewing Garland's 1967 Palace Theatre engagement, disparagingly noted that a "disproportionate part of her nightly claque seems to be homosexual". It goes on to say that "[t]he boys in the tight trousers"[32] would "roll their eyes, tear at their hair and practically levitate from their seats" during Garland's performances. Time then attempted to explain Garland's appeal to the homosexual, consulting psychiatrists who opined that "the attraction [to Garland] might be made considerably stronger by the fact that she has survived so many problems; homosexuals identify with that kind of hysteria" and that "Judy was beaten up by life, embattled, and ultimately had to become more masculine. She has the power that homosexuals would like to have, and they attempt to attain it by idolizing her."[32]

Garland always had a large base of fans in the gay community, which includes Wainwright, who identifies as gay and came out to his parents at the age of 14.[33] A connection is frequently drawn between the timing of Garland's death and funeral, in June 1969, and the Stonewall riots, the flashpoint of the modern Gay Liberation movement.[34] Coincidental or not, the proximity of Garland's death to Stonewall has become a part of LGBT history and lore.[11] Wainwright, having been called the "first post-liberation era gay pop star", was obsessed with The Wizard of Oz (1939) as a child and would dress in his mother's gown, "pretend[ing] to be either the Wicked Witch – melting for hours on end – or the Good Witch, depending on his mood".[11][35] Wainwright also claims his mother (Canadian folk musician Kate McGarrigle) forced him to perform "Over the Rainbow" for guests while growing up, a song he often included in his concert repertoire as an adult.[21]

Wainwright never intended to impersonate Garland or create a drag act, but rather to inhabit the songs and expose them to a new generation.[12] However, there was a certain camp style present, of which Wainwright stated the following: "I think that any gay person in the world would be seduced at one point by a certain kind of camp. For certain people it's kind of a saving grace."[11] Regarding the tribute concerts and homosexuality, Wainwright admitted:

I don't think it would have been possible for anyone other than a gay male to do this concert. In a weird way, a gay man has some sort of perspective on it, I believe.[36]

While Wainwright did not dress in drag at any of the tribute shows in New York or Europe, he did return to the stage in "Judy drag" for an encore at the Hollywood Bowl performance, "bedecked in a double-breasted tuxedo jacket sans pants, black stockings, high heels, earrings, lipstick and a tilted fedora".[24] He also took "Get Happy" from the set and performed the tune "Summer Stock"-style during part of his Release the Stars tour to mimic the look of Garland during her performance (pictured on right).[37]

Critical reception

edit| Aggregate scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 69[38] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [1] |

| Blender | [38][39] |

| Entertainment Weekly | B−[40] |

| The Guardian | [41] |

| Mojo | [42] |

| Pitchfork | 7.5/10[9] |

| Rolling Stone | [43] |

| Slant | [44] |

| The Times | [45] |

| Uncut | [10] |

Overall, reception of the album was positive. Stephen Holden of Blender called Wainwright's tribute "a fabulous stunt in which a gay singer channeled the spirit of the ultimate gay icon", and declared the album was "as good an introduction to the great American songbook as any".[39] Pitchfork Media's Stephen Troussé wrote that Wainwright "elegantly outdoes [Garland] on a couple of the ballads" and also compliments guest performer Martha Wainwright, "who turns in a stunning, showstopping 'Stormy Weather' in an appropriately brazen bid to steal the show".[9] In his review for Rolling Stone, Robert Christgau stated it was "a relief to hear him essay the show tunes and Tin Pan Alley chestnuts of this tribute album". Furthermore, he wrote that the songs "expand [Wainwright's] melodic compass", allowing him to "bring something new to them too – namely, sexuality in the sensuality as opposed to gender-preference sense".[43] Dave Hughes of Slant Magazine had positive comments about the album: "That Wainwright has the temerity to cover such a bona fide classic—and the chops to pull it off without breaking a limb or his brain—speaks both to his ambition and to his prodigious abilities."[44]

The album did receive some criticism. After noting Garland's lifelong attempt to master pitch and articulation, Christgau claimed Wainwright's habit of "slid[ing] past notes and draw[ing] out the final syllables of lines are signatures indistinguishable from tics".[43] Entertainment Weekly's Chris Willman wrote that Wainwright's "delicate upper range is nicely attuned to some of the ballads, but anything that requires belting is pretty much a loss".[40] Mark Edwards of The Times called Wainwright's performance an acquired taste, stating his "trademark delivery" is "lazy and somewhat slurred".[45] Dave Hughes' review pointed out Wainwright's "problem with the brassy high notes in an otherwise energetic take on 'That's Entertainment'", but admits it would be unfair to hold this against him since Garland's live performance was not perfect either. Hughes appropriately notes, "Ain't nobody perfect".[44]

Chart performance and recognition

editDespite the popularity of Wainwright's tribute concerts, an abundance of press regarding the album, and generally favorable critical reception, album sales were limited. However, Rufus Does Judy at Carnegie Hall reached a peak position of number 84 in Belgium, number 88 in the Netherlands and number 171 on the United States' Billboard 200.[6][7][8] The album was nominated for a 2009 Grammy Award for Best Traditional Pop Vocal Album, but lost to Natalie Cole's Still Unforgettable.[46] In 2012, AfterElton.com included the album on its list of "10 Great Pop Culture Moments from Famous Canadians".[47]

| Chart (2007) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Belgian Albums Chart (Flanders) | 84 |

| Netherlands Albums Chart | 88 |

| U.S. Billboard 200 | 171 |

Track listing

editDisc 1

- Overture: "The Trolley Song" / "Over the Rainbow" / "The Man That Got Away"

(Ralph Blane, Hugh Martin) / (Harold Arlen, Yip Harburg) / (Arlen, Ira Gershwin) – 4:15 - "When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With You)" (Mark Fisher, Joe Goodwin, Larry Shay) – 3:44

- Medley: "Almost Like Being in Love" / "This Can't Be Love" (Alan Jay Lerner, Frederick Loewe) / (Richard Rodgers, Lorenz Hart) – 6:10

- "Do It Again" (George Gershwin, Buddy DeSylva) – 5:15

- "You Go to My Head" (J. Fred Coots, Haven Gillespie) – 2:40

- "Alone Together" (Howard Dietz, Arthur Schwartz) – 3:21

- "Who Cares? (As Long as You Care for Me)" (G. Gershwin, I. Gershwin) – 2:08

- "Puttin' On the Ritz" (Irving Berlin) – 1:56

- "How Long Has This Been Going On?" (G. Gershwin, I. Gershwin) – 5:46

- "Just You, Just Me" (Jesse Greer, Raymond Klages) – 2:03

- "The Man That Got Away" (Arlen, I. Gershwin) – 4:59

- "San Francisco" (Walter Jurmann, Gus Kahn, Bronisław Kaper) – 4:53

Disc 2

- "That's Entertainment!" (Dietz, Schwartz) – 2:27

- "I Can't Give You Anything But Love" (Dorothy Fields, Jimmy McHugh) – 8:11

- "Come Rain or Come Shine" (Arlen, Johnny Mercer) – 3:56

- "You're Nearer" (Rodgers, Hart) – 1:58

- "A Foggy Day" (G. Gershwin, I. Gershwin) – 2:55

- "If Love Were All" (Noël Coward) – 2:33

- "Zing! Went the Strings of My Heart" – (James F. Hanley) – 3:48

- "Stormy Weather" (Arlen, Ted Koehler) – 6:45 (performed by Martha Wainwright)

- Medley: "You Made Me Love You" / "For Me and My Gal" / "The Trolley Song" (Joseph McCarthy, James V. Monaco, Roger Edens) / (George W. Meyer, Edgar Leslie, E. Ray Goetz) / (Blane, Martin) – 4:37

- "Rock-a-Bye Your Baby with a Dixie Melody" (Sam M. Lewis, Fred Schwartz, Joe Young) – 5:45

- "Over the Rainbow" (Arlen, Harburg) – 4:47 (featuring Kate McGarrigle)

- "Swanee" (Irving Caesar, G. Gershwin) – 1:54

- "After You've Gone" (Henry Creamer, Turner Layton) – 2:57 (featuring Lorna Luft)

- "Chicago" (Fred Fisher) – 4:30

Bonus track

Track listing adapted from AllMusic.[1]

Personnel

edit- John Engstead – photography

- Frank Filipetti – engineer

- Peter Gary – digital editing

- John Mark Harris – engineer

- Christian Hebel – concert master

- Alex Lake – photography

- John Loengard – photography

- Kate McGarrigle – performer, liner notes

- John Oddo – piano

- Stephen Oremus – conductor, director, performer, musical direction

- Jack Pierson – art direction, photography, cover photo

- Bucky Pizzarelli – guitar

- Kevin Porter – assistant engineer

- B.J. Ramone – assistant engineer

- Phil Ramone – producer

- Vincent Della Rocca – saxophone

- Jim Saporito – drums

- Richard Sarpola – bass

- Ryan Smith – mastering

- Jeanne Venton – A&R

- Martha Wainwright – performer

- Rufus Wainwright – executive producer

- Missy Webb – assistant engineer

Credits adapted from AllMusic.[1]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e "Rufus Does Judy at Carnegie Hall". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ Cox, Gordon (May 28, 2006). "Rufus over the rainbow". Variety. Reed Elsevier. ISSN 0042-2738. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ "Judy at Carnegie Hall". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ "Past Winners Search: Judy at Carnegie Hall". National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on September 25, 2012. Retrieved June 14, 2011.

- ^ "Nominations for the 51st Grammy Awards". USA Today. Gannett Company. December 3, 2008. ISSN 0734-7456. Archived from the original on June 24, 2011. Retrieved June 14, 2011.

- ^ a b "Belgium Charting" (in Dutch). UltraTop.be. Archived from the original on October 2, 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- ^ a b "Rufus Wainwright Dutch Charting". DutchCharts.nl. Archived from the original on February 13, 2009. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- ^ a b "Rufus Does Judy at Carnegie Hall ..." Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Trouss, Stephen (January 7, 2008). "Rufus Wainwright: Rufus Does Judy Live at Carnegie Hall". Pitchfork Media. Archived from the original on March 18, 2009. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Robinson, John (February 2008). "Rufus Does Judy at Carnegie Hall Review". Uncut. IPC Media. ISSN 1368-0722. Archived from the original on July 19, 2008. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Trebay, Guy (June 4, 2006). "Rufus Wainwright Plays Judy Garland". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on May 6, 2014. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ a b Vincentelli, Elisabeth (April 20–26, 2006). "Countdown to Judy – Week 1: Rufus Wainwright". Time Out. Retrieved February 14, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ a b c Vincentelli, Elisabeth (May 4–10, 2006). "Countdown to Judy – Week 3: Jared Geller". Time Out. Archived from the original on February 7, 2008. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Vincentelli, Elisabeth (April 27 – May 3, 2006). "Countdown to Judy – Week 2: Stephen Oremus". Time Out. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ Vincentelli, Elisabeth (May 25–31, 2006). "Countdown to Judy – Week 6: Phil Ramone". Time Out. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ "Rufus! London! Paris! Judy! Let's DO IT AGAIN!". rufuswainwright.com. October 23, 2006. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ "Rufus! London! Judy! One more time!". rufuswainwright.com. November 2, 2006. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ "Rufus to perform at Hollywood Bowl". rufuswainwright.com. January 19, 2007. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ a b Wood, Gaby (June 18, 2006). "Somewhere over the top". The Guardian. London, United Kingdom. ISSN 0261-3077. OCLC 60623878. Archived from the original on September 23, 2014. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ Johnson, Beth (July 7, 2006). "Wish You Were There?". Entertainment Weekly. Time Inc. ISSN 1049-0434. Archived from the original on February 13, 2009. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ a b Empire, Kitty (February 25, 2007). "Rufus Wainwright, London Palladium, W1". The Observer. London, United Kingdom: Guardian Media Group. ISSN 0029-7712. OCLC 50230244. Archived from the original on October 2, 2014. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ "Ode to Antidote – Rufus Wainwright – Viktor & Rolf – Antidote". Viktor & Rolf. August 14, 2006. Archived from the original on November 10, 2009. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ Mower, Sarah (October 2, 2006). "Viktor & Rolf Spring 2007 Ready-to-Wear Collection". Vogue. Condé Nast Publications. ISSN 0042-8000. Archived from the original on February 20, 2009. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ a b Brother, Job (September 26, 2007). "Rufus Hearts Judy". The Advocate. Here Media. ISSN 0001-8996. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ "Rufus at Carnegie Hall Official Posters and T-shirts!". rufuswainwright.com. June 16, 2006. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ "Rufus Wainwright Online Store". Hi Fidelity Entertainment. Archived from the original on January 27, 2009. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ Michaud, Chris (June 16, 2006). "Rufus Wainwright re-creates legendary Judy Garland concert". The Advocate. Here Media. ISSN 0001-8996. Retrieved February 16, 2009.

- ^ "Rufus Wainwright Concert & After-Party". Hint. June 15, 2006. Archived from the original on October 1, 2011. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ Casablanca, Ted (September 25, 2007). "Staged 'n' Engaged". E! Online. Archived from the original on March 5, 2011. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ a b "Rufus Does Judy at Carnegie Hall (UK Bonus Track)". Allmusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ Haggerty, George E. (2000). Gay Histories and Cultures. Garland Publishing, Inc. p. 230. ISBN 0-8153-1880-4.

Gay Histories and Cultures George Haggerty.

- ^ a b "Singers: Seance at the Palace". Time. Time Inc. August 18, 1967. ISSN 0040-781X. Archived from the original on December 15, 2008. Retrieved December 26, 2007.

- ^ Shulman, Randy (March 11, 2009). "The Wainwright Stuff". Metro Weekly. Washington, D.C.: Isosceles Publications. Archived from the original on October 11, 2008. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ Miller, Neil (1995). Out of the Past: Gay and Lesbian History from 1869 to the Present. Vintage UK. p. 367. ISBN 9780099576914.

- ^ Wigney, James (January 7, 2008). "Rufus Wainwright delights in Judy Garland revival". Herald Sun. Melbourne, Australia: The Herald and Weekly Times. Archived from the original on September 9, 2012. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ "Wainwright to Channel Judy Garland, Live". National Public Radio. June 10, 2006. Archived from the original on January 2, 2009. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ "Rufus Wainwright duets with Martha Wainwright at Glastonbury". NME. United Kingdom: IPC Media. June 22, 2007. ISSN 0028-6362. Archived from the original on August 9, 2007. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ a b "Rufus Does Judy at Carnegie Hall – Rufus Wainwright". Metacritic, CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on April 24, 2012. Retrieved June 14, 2011.

- ^ a b Holden, Stephen. "Rufus Wainwright : Rufus Does Judy at Carnegie Hall". Blender. Alpha Media Group Inc. Archived from the original on May 10, 2008. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ^ a b Willman, Chris (November 23, 2007). "Music Review – Rufus Does Judy at Carnegie Hall". Entertainment Weekly. Time Inc. ISSN 1049-0434. Archived from the original on January 7, 2009. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ^ Petridis, Alexis (May 11, 2007). "Rufus Wainwright, Release the Stars". The Guardian. London, United Kingdom. ISSN 0261-3077. OCLC 60623878. Archived from the original on October 3, 2014. Retrieved August 5, 2009.

- ^ Mojo. Bauer Media Group: 98. February 2008. ISSN 1351-0193.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b c Christgau, Robert (February 13, 2007). "Rufus Does Judy at Carnegie Hall". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 22, 2008. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ^ a b c Hughes, Dave (December 4, 2007). "Rufus Does Judy at Carnegie Hall". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on August 23, 2009. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ^ a b Edwards, Mark (January 20, 2008). "Rufus Wainwright: Rufus Does Judy at Carnegie Hall". The Times. London, United Kingdom: News Corporation. ISSN 0140-0460. Archived from the original on June 16, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ^ "The 51st annual Grammy Awards winners list". USA Today. Gannett Company. February 8, 2009. ISSN 0734-7456. Archived from the original on May 22, 2010. Retrieved June 14, 2011.

- ^ Virtel, Louis (July 2, 2012). "10 Great Pop Culture Moments from Famous Canadians". AfterElton.com. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 20, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2012.

External links

edit