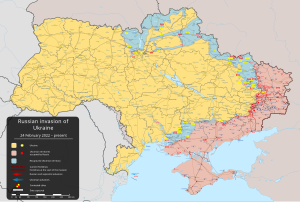

The Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine are areas of southern and eastern Ukraine that are controlled by Russia as a result of the Russo-Ukrainian War and the ongoing invasion. In Ukrainian law, they are defined as the "temporarily occupied territories". As of 2024, Russia occupies almost 20% of Ukraine and about 3 to 3.5 million Ukrainians are estimated to be living under occupation;[1][2] since the invasion, the occupied territories lost roughly half of their population. The United Nations Human Rights Office reports that Russia is committing severe human rights violations in occupied Ukraine, including arbitrary detentions, enforced disappearances, torture, crackdown on peaceful protest and freedom of speech, enforced Russification, passportization, indoctrination of children, and suppression of Ukrainian language and culture.[3]

- In Moldova: Transnistria (1), since 1992

- In Georgia: Abkhazia (2) and South Ossetia (3), since 2008

- In Ukraine: Crimea (4) and parts of Luhansk Oblast (5) and Donetsk Oblast (6) since 2014, and parts of Zaporizhzhia Oblast (7) and Kherson Oblast (8) since 2022

The occupation began in 2014 with Russia's invasion and annexation of Crimea, and its de facto takeover of Ukraine's Donbas[4] during a war in eastern Ukraine.[5] In 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion. However, due to fierce Ukrainian resistance and logistical challenges[6] (e.g. the stalled Russian Kyiv convoy), the Russian Armed Forces retreated from northern Ukraine in early April.[7] In September 2022, Ukrainian forces launched the Kharkiv counteroffensive and liberated most of that province.[8] Another southern counteroffensive resulted in the liberation of Kherson that November.

On 30 September 2022, Russia announced the annexation of Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson provinces, despite only occupying part of the claimed territory. The UN General Assembly passed a resolution rejecting this annexation as illegal and upholding Ukraine's right to territorial integrity.[9]

As of 2024, Ukraine's peace terms call for Russian forces to leave the occupied territories. Russia's terms call for it to keep all the land it occupies, and be given all of the provinces that it claims but does not fully control.[10] Several Western-based analysts say that allowing Russia to keep the land it seized would "reward the aggressor while punishing the victim" and encourage further Russian expansionism.[11][12]

Background

With the Euromaidan and Revolution of Dignity since November 2013, popular protests across Ukraine led to the dismissal of pro-Russian Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych by the Verkhovna Rada (Ukraine's parliament), as he fled to Russia.[13] The growing pro-European sentiment at the center of this period of upheaval caused unease in the Kremlin, and Russian president Vladimir Putin immediately mobilized Russian army and airborne forces to invade Crimea, and they swiftly took control of major government buildings and blockaded the Ukrainian military in their bases across the peninsula.[14] Soon after, Russian-installed officials announced and carried out a referendum for the region to join Russia, which western and independent organizations labeled as illegitimate.[15] The Kremlin rejected these claims and soon officially annexed Crimea into Russia, with western nations issuing sanctions against Russia in response.[16] In addition, with pro-Russian counter-protests across Eastern and Southern Ukraine in response to the ousting of Yanukovych,[17] Russia allegedly supported Russian and pro-Russian militant separatists in the Donbas region in taking control of major government buildings.[18] These separatists eventually created the Donetsk and Luhansk People's Republics,[19] and have since been at conflict with the now-pro-European Ukrainian government, known as the war in Donbas (Russia announced their "annexation" after the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine).

In response to Russian military intervention, the Parliament of Ukraine adopted government laws (with further updates and extensions) to qualify the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and parts of Donetsk and Luhansk regions as temporarily occupied and uncontrolled territories:

- Autonomous Republic of Crimea:

- Law of Ukraine No. 1207-VII (15 April 2014) "Assurance of Citizens' Rights and Freedom, and Legal Regulations on Temporarily Occupied Territory of Ukraine".[20]

- Separate Raions of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts:

- Order of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine No. 1085-р (7 November 2014) "A List of Settlements on Territory Temporarily Uncontrolled by Government Authorities, and a List of Landmarks Located at the Contact Line".[21]

- Law of Ukraine No. 254-19-VIII (17 March 2015) "On Recognition of Separate Raions, Cities, Towns and Villages in Donetsk and Luhansk Regions as Temporarily Occupied Territories".[22]

Petro Poroshenko, one of the opposition leaders during Euromaidan, won a landslide victory in the election to succeed interim president Turchynov, three months after the ousting of Yanukovych.[23]

Timeline

The following chart summarizes some estimates of the total area of Ukrainian territory under Russian control, presented by various publishers at different instances during the conflict. Note that some of the estimates from the end of 2022 were conflicting.

| Date | Percentage of Ukrainian territory (%) |

Area | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 February 2019 | 44,000 km2 (17,000 sq mi) | Petro Poroshenko, U.N.[24] | |

| 29 December 2021 | 43,133 km2 (16,654 sq mi) | CIA World Factbook[25] | |

| 22 February 2022 | 42,000 km2 (16,000 sq mi) | CNN[26] | |

| 28 February 2022 | 119,000 km2 (46,000 sq mi) | CNN[26] | |

| 22 March 2022 | 163,000 km2 (63,000 sq mi) | CNN[26] | |

| 8 April 2022 | 114,000 km2 (44,000 sq mi) | CNN[26] | |

| 2 June 2022 | 119,000 km2 (46,000 sq mi) | Volodymyr Zelenskyy[27] | |

| 31 August 2022 | 125,000 km2 (48,000 sq mi) | CNN[26] | |

| 11 September 2022 | 116,000 km2 (45,000 sq mi) | CNN[26] | |

| 26 September 2022 | 116,000 km2 (45,000 sq mi) | CNN[26] | |

| 11 November 2022 | 119,000 km2 (46,000 sq mi) | CNN[28] | |

| 14 November 2022 | 109,000 km2 (42,000 sq mi) | NY Times[29] | |

| 23 February 2023 | 109,000 km2 (42,000 sq mi) | Belfer center[30] | |

| 25 September 2023 | (0.1% points more than in December 2022) |

~109,000 km2 (42,000 sq mi) (518 km2 more than in December 2022) |

NY Times[31] |

| 20 May 2024 | ~109,000 km2 (42,000 sq mi) | Center for Preventive Action[32] |

Before February 2022

Since Russia annexed Crimea in March 2014, it administers the peninsula under two federal subjects: the Republic of Crimea and the federal city of Sevastopol. Ukraine continues to claim the peninsula as an integral part of its territory, which is supported by most foreign governments through the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 68/262,[33] even though Russia and some other UN member states have expressed support for the 2014 Crimean referendum, implying recognition of Crimea as part of the Russian Federation. In 2015, the Ukrainian parliament officially set 20 February 2014 as the date of "the beginning of the temporary occupation of Crimea and Sevastopol by Russia".[34]

The uncontrolled portions of the Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts are commonly abbreviated as "ORDLO" from Ukrainian, especially among Ukrainian news media. ("certain areas of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts", Ukrainian: Окремі райони Донецької та Луганської областей, romanized: Okremi raiony Donetskoi ta Luhanskoi oblastei)[35] The term first appeared in Law of Ukraine No.1680-VII (October 2014).[36] Documents of the Minsk Protocol and the OSCE refer to them as "certain areas of Donetsk and Luhansk regions" (CADLR) of Ukraine.[37]

The Ministry of Reintegration of Temporarily Occupied Territories is the Ukrainian government ministry that oversees government policy towards the regions.[38] As of 2019[update], the government considered 7% of Ukraine's territory to be under occupation.[39] The United Nations General Assembly resolution 73/194, adopted on 17 December 2018, designated Crimea as under "temporary occupation".[40]

The Ukrainian army was concerned in 2019 about the deployment of 3M-54 Kalibr cruise missiles on Russian naval and coast guard vessels operating in the Sea of Azov, which is adjacent to the temporarily occupied territories. As a result, Mariupol and Berdiansk, two main Pryazovian seaports, suffer from an increase in insecurity[41] (both cities were captured in 2022).

Temryuk and Taganrog, two other ports on the Sea of Azov, have allegedly been used to disguise the provenance of anthracite coal and liquefied natural gas (LNG) from the temporarily occupied territories.[41]

Territories affected

Since the start of the Russo-Ukrainian War in 2014, the Government of Ukraine is issuing (as extension to government order no. 1085-р and law no. 254-VIII) up-to-date "List of Temporarily Occupied Regions and Settlements" and a "List of Landmarks Bordering the Anti-Terrorist Operation Zone".[43] As of 16 September 2020, the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine has made four updates to order no. 1085-р and law no. 254-VIII:

- Addendum No. 128-р as of 18 February 2015[44]

- Addendum No. 428-р as of 5 May 2015[45]

- Addendum No. 1276-р as of 2 December 2015[46]

- Addendum No. 79-р as of 7 February 2018[47]

- Addendum No. 410-р as of 13 June 2018[48]

- Addendum No. 505-р as of 5 July 2019[49]

- Addendum No. 1125-р as of 16 September 2020[50]

Some settlements' names are the result of 2016 Decommunization in Ukraine.[51][52]

The list below is based on the extension as of 7 February 2018. The borders of some raions have changed since 2015.

- Autonomous Republic of Crimea (entire region)

- Donetsk Oblast

- Cities of regional importance and nearby settlements:

- Donetsk

- Horlivka

- Debaltseve

- Dokuchaievsk

- Yenakiieve

- Zhdanivka

- Khrestivka

- Makiivka

- Snizhne

- Chystiakove

- Khartsyzk

- Shakhtarsk

- Yasynuvata

- Amvrosiivka Raion (all settlements)

- Bakhmut Raion:

- Bulavynske

- Vuhlehirsk

- Oleksandrivske

- Olenivka

- Vesela Dolyna

- Danylove

- Illinka

- Kamianka

- Bulavyne

- Hrozne

- Kaiutyne

- Vozdvyzhenka

- Stupakove

- Savelivka

- Debaltsivske

- Kalynivka

- Lohvynove

- Novohryhorivka

- Nyzhnie Lozove

- Sanzharivka

- Olkhovatka

- Pryberezhne

- Dolomitne

- Travneve

- Lozove

- Volnovakha Raion:

- Andriivka

- Dolia

- Liubivka

- Malynove

- Molodizhne

- Novomykolaivka

- Nova Olenivka

- Petrivske

- Chervone

- Pikuzy

- Mariinka Raion:

- Kreminets

- Luhanske

- Oleksandrivka

- Staromykhailivka

- Syhnalne

- Novoazovsk Raion (all settlements)

- Starobesheve Raion (all settlements)

- Boikivske Raion (all settlements)

- Shakhtarsk Raion (all settlements)

- Yasynuvata Raion:

- Vesele

- Bétmanove

- Mineralne

- Spartak

- Yakovlivka

- Kruta Balka

- Kashtanove

- Lozove

- Vasylivka

- Cities of regional importance and nearby settlements:

- Luhansk Oblast

- Cities of regional importance and nearby settlements:

- Luhansk

- Alchevsk

- Antratsyt

- Brianka

- Holubivka

- Khrustalnyi

- Sorokyne

- Pervomaisk (known as Oleksandrivka)

- Rovenky

- Dovzhansk

- Kadiivka

- Antratsyt Raion (all settlements)

- Sorokyne Raion (all settlements)

- Lutuhyne Raion (all settlements)

- Novoaidar Raion:

- Sokilnyky

- Perevalsk Raion (all settlements)

- Popasna Raion:

- Berezivske

- Holubivske

- Zholobok

- Kalynove

- Kalynove-Borshchuvate

- Kruhlyk

- Molodizhne

- Mius

- Novooleksandrivka

- Chornukhyne

- Zolote (except Zolote-1,2,3,4)

- Dovzhánsk Raion (all settlements)

- Slovianoserbsk Raion (all settlements)

- Stanytsia Luhanska Raion:

- Burchak-Mykhailivka

- Lobacheve

- Mykolaivka

- Sukhodil

- Cities of regional importance and nearby settlements:

- Sevastopol (entire city)

Since the 2022 invasion

After Russia's full-scale invasion in February 2022, the Russian military and Russian proxy forces further occupied additional Ukrainian territory. By early April, Russian forces withdrew from Northern Ukraine, including the capital Kyiv,[53] after stagnating progress amid fierce Ukrainian resistance in order to focus on consolidating control over Eastern and Southern Ukraine. On June 2, 2022, Zelenskyy announced that Russia occupied approximately 20% of Ukrainian territory.[27]

Before 2022, Russia occupied 42,000 km2 (16,000 sq mi) of Ukrainian territory (Crimea, and parts of Donetsk and Luhansk), and occupied a further 119,000 km2 (46,000 sq mi) after its full-scale invasion by March 2022, a total of 161,000 km2 (62,000 sq mi) or almost 27% of Ukraine.[26] By 11 November 2022, the Institute for the Study of War calculated that Ukrainian forces had liberated an area of 74,443 km2 (28,743 sq mi) from Russian occupation,[54] leaving Russia with control of about 18% of Ukraine.[55] During the whole of 2023, Russian forces only captured 518 km2 (200 sq mi) of Ukrainian territory, despite huge losses on the battlefield.[31]

As of 2024, Ukraine's peace terms include Russia withdrawing its troops from the occupied territories. Russia's terms include Russia keeping all the land it occupies, and being given all of the provinces that it claims but does not fully control.[10]

Several Western-based analysts say that allowing Russia to keep the land it seized would "reward the aggressor while punishing the victim" and set a dangerous precedent.[11] They predict that this would encourage Russia "to continue its imperialist campaign of expansionism" against Ukraine and its other neighbors, and embolden other expansionist regimes.[11][56][57][58][59] Zelenskyy commented: "It's the same thing Hitler did, when he said 'give me a part of Czechoslovakia and it'll end here'."[60] Leo Litra of the European Council on Foreign Relations pointed out that allowing Russia to annex Crimea in 2014 did not stop further Russian aggression. Opinion polls show that the majority of Ukrainians oppose giving up any of their country for peace.[61]

Kharkiv Oblast

The occupation began on February 24, 2022, immediately after Russian troops invaded Ukraine and began seizing parts of the Kharkiv Oblast. Since April, Russian forces tried to consolidate control in the region and capture the major city of Kharkiv after their withdrawal from Northern Ukraine. However, by mid-May, the Ukrainian forces pushed the Russians back towards the periphery of the Russian border,[62] indicating that Ukrainians continue to garner stiff resistance against Russian advances. In early September 2022, Ukrainian forces began a major counteroffensive and by 11 September 2022, Russia had retreated from most of the settlements it previously occupied in the oblast,[63] and the Russian Ministry of Defense announced a formal withdrawal of Russian forces from nearly all of Kharkiv Oblast stating that an "operation to curtail and transfer troops" was underway."[64][65]

Kherson Oblast

On February 24, 2022, Russian troops from Crimea invaded Henichesk and Skadovsk Raions. During the first days of the offensive, the Russians surrounded most of the cities and towns in the oblast, blocking the entrances to them with roadblocks, but not entering the cities themselves. Significant battles were fought for the Antonivskyi Bridge, which crosses the Dnipro River between Russian positions on the South bank and the Ukrainian city of Kherson on the North bank. The Russian military's overwhelming firepower forced the Ukrainian forces to retreat, and the city fell to Russian control on March 2.[67] On June 29, the Russian occupation authorities in Kherson Oblast announced preparations for holding a referendum of annexation.[68] On July 9, the Ukrainian government announced preparations for an imminent counteroffensive in the South, and urged the residents of occupied parts of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia Oblasts to shelter or evacuate to minimize civilian casualties in the operation.[69] Following the destruction of the Antonivskyi Bridge and the advance of Ukrainian troops from the west, the lack of sustainable supply lines amid heavy Ukrainian shelling compelled the Russian forces to retreat. They eventually retreated from all areas on the North bank of the Dnipro River, including the city of Kherson, which the Ukrainian forces recaptured soon after, known as the liberation of Kherson.

Raions of Kherson Oblast that are occupied:

Zaporizhzhia Oblast

On February 26, 2022, the city of Berdiansk came under Russian control, followed by Melitopol on March 1 after fierce fighting between Russian and Ukrainian forces. Russian troops also besieged and captured the city of Enerhodar, where the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant is located, which came under Russian control on March 4. Since July, there have been increased tensions around the power plant as both Russia and Ukraine accuse each other of missile strikes around the plant,[70] causing fears of a potential repeat of the Chernobyl Disaster.

Raions of Zaporizhzhia Oblast that are occupied:

- Melitopol Raion

- Berdiansk Raion

- Most of Vasylivka Raion

- Most of Polohy Raion

Donetsk Oblast

Since the invasion, the Russian military, along with the Russian-backed Donetsk People's Republic, built on territorial gains they have made during the war in Donbas and captured additional territory, most significantly the port of Mariupol after a prolonged siege.

By February 24, 2022, the following raions of Donetsk Oblast were occupied:

After February 24, 2022, the following raions of Donetsk Oblast were captured:

- Mariupol Raion

- Half of Volnovakha Raion

- Portions of Bakhmut Raion, Kramatorsk Raion, and Pokrovsk Raion

Luhansk Oblast

By February 24, 2022, the following raions of Luhansk Oblast were occupied:

After February 24, 2022, the following raions of Luhansk Oblast were captured:

- Shchastia Raion

- Staroblisk Raion

- Most of Svatove Raion

- Most of Sievierodonetsk Raion

On July 3, 2022, the Russian military claimed that the entire Luhansk Oblast has been "liberated",[73] suggesting that Russian forces has succeeded in occupying the entire oblast and marked a major milestone for their goal of capturing the Donbas in Eastern Ukraine.

However, by September 19, Ukraine recaptured Bilohorivka.[74] By early October, Ukrainian forces liberated several more settlements as their counteroffensive operations shifted focus into the main territory of the oblast,[75] specifically the half north of the Siverskyi Donets in the Battle of the Svatove–Kreminna line. By May 2024, Ukraine had again lost control of Bilohorivka.[76]

Mykolaiv Oblast

The occupation of Mykolaiv Oblast began on February 26, 2022, with Russian troops crossing into the oblast through the Kherson Oblast from Crimea. In March, Russia attempted to advance towards Voznesensk, Mykolaiv and Nova Odesa, but were met with stiff resistance and failed. By May, Russia occupied Snihurivka, Tsentralne, Novopetrivka and numerous other small villages within the oblast. All these were retaken on 10–11 November 2022 during the Ukrainian counteroffensive, which followed the withdrawal of Russian troops from the right bank of the Dnieper.

Raions of Mykolaiv Oblast that are occupied:

- Extreme southern portion of Mykolaiv Raion (Kinburn Peninsula)

Formerly occupied territories

Chernihiv Oblast

Russia started the occupation as part of the northern campaign in the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The occupying forces occupied a large part of the oblast, and eventually laid siege to the oblast capital, but failed to capture the city. Eventually, their stagnant progress led to their complete withdrawal from the oblast by early April, ending the occupation.

Dnipropetrovsk Oblast

By April 2022, Russian troops began to secure towns north of Mariupol, most notably the Battle of Volnovakha, and completed the encirclement of Mariupol.[77] They then began to attack towns to the north, including starting the Battle of Velyka Novosilka.[78] As the Russians advanced, there were reports of clashes[by whom?] near Ternove, Novomykolaivka, Kalynivske, Berezove, Stepove and Maliivka, all in Synelnykove Raion, bordering Zaporizhzhia and Donetsk Oblasts, partially occupied by Russian forces. Ukrainian forces reported small battles near the Ternove area on 1 March.[79][citation not found] Ukrainian forces claimed to have cleared out Russian troops from the area on 14 March.[80][failed verification] These areas alongside Nikopol and Apostolove are still regularly shelled.[81][82][83] On 16 March, Russian forces spilled over from Kherson Oblast into Hannivka, reportedly occupying it.[84][better source needed] It was later liberated on 11 May.[85]

Kyiv Oblast

Russia started the occupation as part of the northern offensive in the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Russian troops occupied a large part of the oblast, even approaching the borders of Kyiv city proper. However, the invaders' stagnant progress led to their failure to capture the Ukrainian capital, and eventually led to a complete withdrawal from the oblast by early April, ending the occupation.

Odesa Oblast

From 24 February to 30 June 2022, Russian forces occupied Snake Island in Odesa Oblast, but later withdrew after suffering heavy missile, artillery and drone strikes from the Ukrainian forces.[86]

Poltava Oblast

During the battles of Lebedyn and Okhtyrka, Sumy Oblast, Russian forces spilled over and attacked Hadiach on 4 March 2022,[87][88][better source needed] and captured small areas around it, and advanced near Zinkiv and occupied Pirky on 3 March, but were repelled.[89][90] They were soon afterwards repelled which was known as the "Hadiach Safari", since people used shotguns and rifles to hunt for Russian soldiers.[91] Some notable areas captured were Pirky and Bobryk.[92]

Sumy Oblast

Russia started the occupation as part of the northern offensive in the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The Russian military occupied a large part of the oblast, but failed to take the oblast capital. Eventually, the stagnant progress of the Russian Ground Forces led to their complete withdrawal from the oblast by early April, ending the occupation.

Zhytomyr Oblast

Russia started the occupation as part of the Northern offensive in the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The Russians occupied a small portion of the oblast, and never attempted to capture the oblast capital. Eventually, the culmination of the drive on Kyiv led to their complete withdrawal from the oblast by early April, ending the occupation.

Russian occupation governments

| Occupied Ukrainian regions | Existing Russian-established entities and regimes | Date of unilateral annexation by Russia |

|---|---|---|

| Autonomous Republic of Crimea | Republic of Crimea | 18 March 2014 |

| Donetsk Oblast | Donetsk People's Republic | 30 September 2022 |

| Kharkiv Oblast | Kharkov Military-Civil Administration | Not annexed |

| Kherson Oblast | Kherson Oblast | 30 September 2022 |

| Luhansk Oblast | Lugansk People's Republic | 30 September 2022 |

| Zaporizhzhia Oblast | Zaporozhye Oblast | 30 September 2022 |

Violations and war crimes

The United Nations Human Rights Office reports that Russia is committing severe human rights violations in occupied Ukraine. These include arbitrary detentions, torture, looting, and enforced disappearances by Russian soldiers acting with "impunity". Peaceful protests and freedom of speech have been suppressed, while freedom of movement is severely restricted.[3] Anyone suspected of opposing the occupation has been targeted, while people have been "encouraged to inform on one another, leaving them afraid even of their own friends and neighbours".[3]

Ukrainians have been coerced into taking Russian passports and becoming Russian citizens. Those who refuse are denied healthcare, freedom of movement, public sector employment and social security benefits.[3] From July 2024, anyone in occupied Ukraine who does not have a Russian passport can be imprisoned as a "foreign citizen". Ukrainian men who take a Russian passport are then drafted to fight against the Ukrainian army.[93]

The UN reports that Ukrainian children are the worst affected. Schools are forced to teach the Russian curriculum, with textbooks that seek to justify the invasion.[3] Children are also enlisted into youth groups that indoctrinate them with Russian nationalism.[3] There are reports of parents who refuse Russian passports having their children taken away from them.[94] The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe recognized Russia's abduction and deportation of Ukrainian children as genocidal.[95]

Ukrainian language and media has been replaced by Russian language and media.[3]

Russia has been accused of neo-colonialism and colonization in Crimea by enforced Russification, passportization, and by settling Russian citizens on the peninsula and forcing out Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars.[96]

Suppression of Ukrainian culture

United Nations special rapporteurs have condemned the Russian occupation authorities for attempting "to erase local [Ukrainian] culture, history, and language" and to forcibly replace it with Russian language and culture. Monuments and places of worship have been razed, while Ukrainian history books and literature deemed to be "extremist" have been seized from public libraries and destroyed. Civil servants and teachers have been detained for their refusal to implement Russian policy.[97] The International Court of Justice ruled that Russia had broken the Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination by restricting school classes in the Ukrainian language in occupied Crimea.[98]

Resistance

Collaboration

Following the liberation of occupied territories, thousands of civilians were accused of collaboration. They are tried by a single judge without a jury. The offense is punished by up to ten years of prison, with some of those convicted getting three or five years of prison. The accused include people who worked as volunteers and held administrative positions during the occupation.[99]

International reactions

On 20 April 2016 Ukraine officially established government Ministry of Temporarily Occupied Territories and Internally Displaced Persons.[38] It was subsequently renamed the Temporarily Occupied Territories, IDPs and veterans and then the Ministry of Reintegration of Temporarily Occupied Territories. The current minister is Iryna Vereshchuk, appointed on 4 November 2021.[100]

In March 2014, in a vote at the United Nations, 100 member states out of 193[101] did not recognize the annexation of the Crimea by Russia, with only Armenia, Belarus, Bolivia, Cuba, Nicaragua, North Korea, Russia, Sudan, Syria, Venezuela, Zimbabwe voting against the resolution[102] (see United Nations General Assembly Resolution 68/262).

The United Nations passed three resolutions regarding the issue of "human rights in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol", first in December 2016,[103] then again a year later in December 2017,[104] and lastly yet another in December 2018.

The UN's position according to the resolution adopted in 2018:

Condemning the ongoing temporary occupation of part of the territory of Ukraine, namely, the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol (hereinafter referred to as "Crimea"), by the Russian Federation, and reaffirming the non-recognition of its annexation[40]

In April 2018, PACE's emergency assembly recognized occupied regions of Ukraine as "territories under effective control by the Russian Federation".[105][106] Chairman of the Ukrainian delegation to PACE, MP Volodymyr Aryev mentioned that recognition of the fact that part of the occupied Donbas is under Russia's control is so important for Ukraine. "The responsibility for all the crimes committed in the uncontrolled territories is removed from Ukraine. Russia becomes responsible", Aryev wrote on Facebook.[107]

In early March 2022, in response to Russia's invasion, the United Nations General Assembly convened an emergency special session to discuss the latest developments regarding the peace situation in Ukraine, and adopted the United Nations General Assembly Resolution ES-11/1 to condemn Russia's invasion and Belarus's involvement.[108]

See also

- 2022 protests in Russian-occupied Ukraine

- List of military occupations

- Joint Forces Operation (Ukraine)

- Malaysia Airlines Flight 17

- Russian military presence in Transnistria

- Russian-occupied territories

- Russian-occupied territories in Georgia

- Russian temporary administrative agencies in Occupied Ukraine

- Territorial control during the Russo-Ukrainian War

- Ukrainian occupation of Kursk Oblast

References

- ^ Fredrik Wesslau (24 February 2024). "There Must Be a Reckoning for Russian War Crimes". Foreign Policy.

- ^ Nikolay Petrov (5 September 2024). "Russia in the Occupied Territories of Ukraine: Policies, Strategies and Their Implementation". Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik.

- ^ a b c d e f g "UN report details 'climate of fear' in Russian occupied areas of Ukraine". UN News. 20 March 2024.

- ^ Plokhy, Serhii (2023). The Russo-Ukrainian war: the return of history. New York, NY: WW Norton. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-324-05119-0.

- ^ Migacheva, Katya; Oberholtzer, Jenny; Nichiporuk, Brian; Radin, Andrew; Kofman, Michael; Tkacheva, Olesya (2017). Lessons from Russia's Operations in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation. p. 44. ISBN 978-0833096067.

- ^ "Why the Russian military is bogged down by logistics in Ukraine". The Washington Post. 30 March 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ Hunder, Max (4 April 2022). "Ukraine's northern regions say Russian troops have mostly withdrawn". Reuters. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ "Russian troops retreat as Ukrainian counteroffensive makes rapid progress". CBS News. 11 September 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ "So-called referenda in Russian-controlled Ukraine 'cannot be regarded as legal': UN political affairs chief". UN News. 27 September 2022. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Putin lays out his terms for ceasefire in Ukraine". BBC News. 14 June 2024. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

"Vladimir Putin issues fresh demands to Ukraine to end war". The Guardian. 14 June 2024. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

"Putin states Ukrainian Armed Forces must withdraw from 4 Ukrainian oblasts to begin peace talks". Ukrainska Pravda. 14 June 2024. Retrieved 14 June 2024. - ^ a b c "How to end Russia's war on Ukraine". Chatham House. 3 October 2023.

- ^ "Global Perspectives on Ending the Russia-Ukraine War". Council of Councils. Council on Foreign Relations. 21 February 2024.

- ^ Frizell, Sam (22 February 2014). "Ukraine Protestors Seize Kiev As President Flees". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ Higgins, Andrew; Erlanger, Steven (27 February 2014). "Gunmen Seize Government Buildings in Crimea". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ "Crimea Overwhelmingly Supports Split From Ukraine To Join Russia". NPR.org. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ Myers, Steven Lee; Baker, Peter (17 March 2014). "Putin Recognizes Crimea Secession, Defying the West". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ "Pro-Russia protests in Ukraine". BBC News. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine: Pro-Russians storm offices in Donetsk, Luhansk, Kharkiv". BBC News. 6 April 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine's rebel 'people's republics' begin work of building new states". the Guardian. 6 November 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ "Про забезпечення прав і свобод громадян та правовий режим на тимчасово окупованій території України" [On ensuring the rights and freedoms of citizens and the legal regime in the temporarily occupied territory of Ukraine]. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ^ "Про затвердження переліку населених пунктів, на території ... – від 07.11.2014 № 1085-р". zakon4.rada.gov.ua. Archived from the original on 23 February 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ "Про визнання окремих районів, міст, селищ і сіл Донецької та Луганської областей тимчасово окупованими територіями" [About recognition of separate areas, cities, settlements and villages of Donetsk and Luhansk areas as temporarily occupied territories]. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ^ "Petro Poroshenko claims Ukraine presidency". BBC News. 25 May 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ "Speakers Urge Peaceful Settlement to Conflict in Ukraine, Underline Support for Sovereignty, Territorial Integrity of Crimea, Donbas Region". U.N. Meetings Coverage and Press Releases. 20 February 2019.

- ^ "Ukraine - The World Factbook". www.cia.gov. 29 December 2021.

approximately 43,133 sq km, or about 7.1% of Ukraine's area, is Russian occupied; the seized area includes all of Crimea and about one-third of both Luhans'k and Donets'k oblasts.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Croker, Natalie; Manley, Byron; Lister, Tim (30 September 2022). "The turning points in Russia's invasion of Ukraine". CNN.

Territory under assessed Russian control or advances

- ^ a b "Zelenskiy: Russia occupies over 20% of Ukraine's territory". Reuters. 2 June 2022.

- ^ Hansley, Jennifer (16 November 2022). "Top US general: Ukraine "kicking the Russians physically out" of country not likely to happen soon". CNN.

- ^ Scott Reinhard (14 November 2022). "Maps: Tracking the Russian Invasion of Ukraine - Ukraine has reclaimed more than half the territory Russia has taken this year". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022.

- ^ "Russia-Ukraine Report Card | Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs". www.belfercenter.org. 23 February 2023.

- ^ a b Josh Holder (28 September 2023). "Who's Gaining Ground in Ukraine? This Year, No One". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ Center for Preventive Action, at the Council on Foreign Relations (20 May 2024). "War in Ukraine". Global Conflict Tracker. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ "Kremlin: Crimea and Sevastopol are now part of Russia, not Ukraine". CNN. 18 March 2014. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ^ ""Няша" Поклонська обіцяє бійцям "Беркута" покарати учасників Майдану". www.segodnya.ua (in Ukrainian). 11 July 2022. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ "Poroshenko signs law extending ORDLO special status". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 7 October 2017. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ^ Про особливий порядок місцевого самоврядування в окремих районах Донецької та Луганської областей [On the special order of local self-governance in separate raions of the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts] (in Ukrainian). Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, Legislation of Ukraine. 10 October 2017. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ "Press Statement of Special Representative Grau after the regular Meeting of Trilateral Contact Group on 22 July 2020". osce.org. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ^ a b У Гройсмана створили нове міністерство [The Cabinet decided to create the Ministry of temporarily occupied territories and internally displaced persons], Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian), 20 April 2016, archived from the original on 28 March 2019, retrieved 26 January 2017

- ^ "Speakers Urge Peaceful Settlement to Conflict in Ukraine, Underline Support for Sovereignty, Territorial Integrity of Crimea, Donbas Region". United Nations. 20 February 2019. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ a b "General Assembly Adopts Resolution Urging Russian Federation to Withdraw Its Armed Forces from Crimea, Expressing Grave Concern about Rising Military Presence". United Nations. 17 December 2018. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ a b Hurska, Alla (12 February 2019). "Russia's Hybrid Strategy in the Sea of Azov: Divide and Antagonize (Part Two)". Vol. 16, no. 18. The Jamestown Foundation. Eurasia Daily Monitor. Archived from the original on 13 February 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ "In the Donbas region, 20 years of Russian propaganda led to war". Le Monde. 23 April 2022.

- ^ "Про затвердження переліку населених пунктів, на території яких органи державної влади тимчасово не здійснюють свої повноваження, та переліку населених пунктів, що розташовані на лінії розмежування" [List of Temporarily Occupied Regions and Settlements]. Офіційний вебпортал парламенту України (in Ukrainian).

- ^ "Про внесення змін у додаток до розпорядження Кабінету Міні... – від 18.02.2015 № 128-р" [On amendments to the appendix to the order of the Cabinet of Ministers ... – dated 18.02.2015 № 128-r]. Офіційний Вебпортал Парламенту України. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ "Про внесення змін до розпорядження Кабінету Міністрів Укра... – від 05.05.2015 № 428-р" [On amendments to the order of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine ... – dated 05.05.2015 № 428-r]. zakon4.rada.gov.ua. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ "Про внесення змін у додатки 1 і 2 до розпорядження Кабінет... – від 02.12.2015 № 1276-р" [On amendments to Annexes 1 and 2 to the order of the Cabinet ... – from 02.12.2015 № 1276-r]. zakon4.rada.gov.ua. Archived from the original on 9 April 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ "Про внесення змін у додатки 1 і 2 до розпорядження Кабінету Міністрів України від 7 листопада 2014 р. № 1085 від від 7 лютого 2018 р. № 79-р" [On Amendments to Annexes 1 and 2 to the Order of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine of November 7, 2014 № 1085 of February 7, 2018 № 79-r]. zakon4.rada.gov.ua. Archived from the original on 25 April 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ^ "Про внесення змін у додатки 1 і 2 до розпорядження Кабінету Міністрів України від 7 листопада 2014 р. № 1085 (410–2018)" [On Amendments to Annexes 1 and 2 to the Order of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine of November 7, 2014 № 1085 (410–2018)]. zakon.rada.gov.ua. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ^ "Про внесення змін у додатки 1 і 2 до розпорядження Кабінету Міністрів України від 7 листопада 2014 р. № 1085 (505–2019)" [On Amendments to Annexes 1 and 2 to the Order of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine of November 7, 2014 № 1085 (505–2019)]. Офіційний Вебпортал Парламенту України. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ^ "Про внесення змін у додатки 1 і 2 до розпорядження Кабінету Міністрів України від 7 листопада 2014 р. № 1085 (1125–2020)" [On Amendments to Annexes 1 and 2 to the Order of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine of November 7, 2014 № 1085 (1125–2020)]. zakon.rada.gov.ua. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ^ "Офіційний портал Верховної Ради України (Донецька область)" [Official portal of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (Donetsk region)]. w1.c1.rada.gov.ua. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ "Офіційний портал Верховної Ради України (Луганська область)" [Official portal of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (Luhansk region)]. w1.c1.rada.gov.ua. Archived from the original on 9 April 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ "Russian Forces Pull Back From Kyiv and Chernihiv". WSJ. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ "Ukrajina od února osvobodila území o velikosti Česka". DenikN (in Czech). 13 November 2022.

- ^ "Maps: Tracking the Russian Invasion of Ukraine". The New York Times. 14 February 2022. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ "Global Perspectives on Ending the Russia-Ukraine War". Council of Councils. Council on Foreign Relations. 21 February 2024.

- ^ Karatnycky, Adrian (19 December 2023). "What a Russian Victory Would Mean for Ukraine". Foreign Policy.

- ^ Danylyuk, Oleksandr (24 January 2024). "What Ukraine's Defeat Would Mean for the US, Europe and the World". Royal United Services Institute.

- ^ Beketova, Elena (20 October 2023). "Russian Victory Would Bring Darkness to the Heart of Europe". Center for European Policy Analysis.

- ^ "Putin lays out his terms for ceasefire in Ukraine". BBC News. 14 June 2024. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ Litra, Leo (5 November 2024). "The US election, Ukraine, and the meaning of peace". European Council on Foreign Relations.

- ^ "Troops defending Kharkiv reached Russian border, Ukraine says". Reuters. 16 May 2022. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine recaptures territory from Russian forces in Kharkiv". NBC News. 11 September 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "Russian defense ministry shows retreat from most of Kharkiv region". Meduza. 11 September 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ Russian Defence Ministry Showed Map Of New Frontline In Kharkiv Region, Хартии'97, 11 September 2022.

- ^ Bershidsky, Leonid (15 June 2022). "Putin Prepares to Declare Himself a Conqueror". Bloomberg.

- ^ Schwirtz, Michael; Pérez-Peña, Richard (2 March 2022). "First Ukraine City Falls as Russia Strikes More Civilian Targets". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ "Moscow-administered Kherson prepares referendum on joining Russia". Reuters. 29 June 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ "Residents of Kherson Oblast are urged to prepare shelters to "survive the counteroffensive of the Armed Forces of Ukraine"". Ukrainska Pravda. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ "Moscow, Kyiv exchange accusations after Ukrainian nuclear plant shelled". Reuters. 5 August 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ "Vladimir Putin's false war claims". Deutsche Welle. 25 February 2022.

- ^ "'Smells of genocide': How Putin justifies Russia's war in Ukraine". Al Jazeera. 9 March 2022.

- ^ "Russia says its forces now have full control of east Ukraine region". CNBC. 3 July 2022. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ "Governor: Ukraine liberates Bilohorivka village in Luhansk Oblast". The Kyiv Independent. 19 September 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ Lester, Tim (5 October 2022). "Ukrainian forces advance into Luhansk region for first time since conflict began, social media images show". CNN. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ Lowe, Yohannes; Bayer, Lili (20 May 2024). "Russia-Ukraine war: Russia to make further bid to carve out 'buffer zone' in coming weeks, warns US defence secretary – as it happened". the Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Chazan, Guy; Reed, John (5 March 2022). "'They are trying to exterminate us': Mariupol comes under Russian onslaught". Financial Times.

- ^ Walsh, Joe. "Most Russian Troops Have Left Mariupol, U.S. Believes". Forbes. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ "dev-isw.bivings.com".

- ^ "Держспецзв'язку". Telegram. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ "Russian troops shell Dnipropetrovsk Oblast with heavy artillery". Yahoo News. 28 January 2023. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ "Russia fires about 100 shells in Nikopol district in a day: dozens of houses damaged". Yahoo News. 3 March 2023.

- ^ "Eight private houses damaged as enemy shells Nikopol district". www.ukrinform.net. 27 February 2023.

- ^ "Assessed Control of Terrain in Ukraine and Main Russian Maneuver Axes as of March 16, 2022, 3:00 PM ET". www.understandingwar.org.

- ^ "Assessed Control of Terrain Around Kherson and Mykolaiv as of May 11, 2022, 3:00 PM ET". www.understandingwar.org.

- ^ "Snake Island: Why Russia couldn't hold on to strategic Black Sea outcrop". BBC News. 30 June 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ Schlottman, Henry [@HN_Schlottman] (27 February 2022). "This is also making the rounds on social media: a Russian armored vehicle reportedly fell into a river near Hadyach (Гадяч). https://t.co/SyMIPkJMq5 https://t.co/KAcrFEN8Hn" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Вражескую колонну остановил старый мост: под.. | Victor Yarmoshuk | VK". vk.com. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ "The Battle of Ukraine, Special Issue 3, 1 March 2022, 18:00 Kyiv Time".

- ^ "The Battle of Ukraine, Special Issue 4, 3 March 2022, 18:00 Kyiv Time".

- ^ ""Hadiach Safari": in the north of Poltava region, hunters took away 10 tanks and other equipment from the enemy – Rubryka". 18 March 2022.

- ^ "DeepStateMAP | Мапа війни в Україні". DeepStateMap.Live (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ "Takeaways into AP investigation into Russian system to force its passports on occupied Ukraine". Associated Press. 15 March 2024.

- ^ "Ukraine war: Locals forced to take Russian passports, report says". BBC News. 16 November 2023.

- ^ "Ombudsman says Putin's 'deportation' decree an attempt to 'intimidate' in people in occupied territories". Yahoo News. New Voice of Ukraine. 28 April 2023.

- ^ Yermakova, Olena (August 2021). "The silent Russian colonisation of Crimea". New Eastern Europe.

- ^ "Targeted destruction of Ukraine's culture must stop: UN experts". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 22 February 2023.

- ^ "Russia Ukraine war: ICJ finds Moscow violated terrorism and anti-discrimination treaties". BBC News. 31 January 2024.

- ^ "I was jailed by Ukraine for 'collaborating with Russia' for keeping my town's lights on". The Times. 30 September 2023. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ "Vereshchuk appointed Ukraine's deputy prime minister". www.ukrinform.net. 4 November 2021. Archived from the original on 30 November 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ^ General Assembly Sixty-eighth session, 80th plenary meeting Thursday, 27 March 2014, 10 a.m., United Nations, 27 March 2014, p. 17, A/68/PV.80 and 14-27868, archived from the original on 28 July 2018, retrieved 22 October 2018

- ^ United Nations General Assembly, Sixty-eighth session, Agenda item 33 (b), Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 27 March 2014 [without reference to a Main Committee (A/68/L.39 and Add.1)] 68/262. Territorial integrity of Ukraine, United Nations, 1 April 2014, A/RES/68/262, archived from the original on 6 October 2019, retrieved 22 October 2018 Alternative URL Archived 2018-10-23 at the Wayback Machine

General Assembly Adopts Resolution Calling upon States Not to Recognize Changes in Status of Crimea Region, United Nations, 27 March 2014, GA/11493, archived from the original on 14 September 2019, retrieved 22 October 2018 - ^ Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 19 December 2016, on the report of the Third Committee (A/71/484/Add.3), 71/205. Situation of human rights in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol (Ukraine), United Nations, 1 February 2017, A/RES/71/205, archived from the original on 25 October 2018, retrieved 22 October 2018

United Nations General Assembly, Seventy-first session, 65th plenary meeting, Monday, 19 December 2016, 10 a.m. New York, United Nations, 18 December 2016, pp. 34–43, A/RES/71/205, archived from the original on 24 October 2018, retrieved 22 October 2018

General Assembly Adopts 50 Third Committee Resolutions, as Diverging Views on Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity Animate Voting, United Nations, 19 December 2016, GA/11879, archived from the original on 19 December 2017, retrieved 22 October 2018 - ^ Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 19 December 2017 [on the report of the Third Committee (A/72/439/Add.3)] 2/190. Situation of human rights in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol, Ukraine, United Nations, 19 January 2018, A/RES/72/190, archived from the original on 25 July 2018, retrieved 22 October 2018 Alternative URL (pdf) Archived 2018-10-23 at the Wayback Machine

United Nations General Assembly, Seventy-second session, Agenda item 72 (c), Promotion and protection of human rights: human rights situations and reports of special rapporteurs and representatives, 6 December 2017, pp. 22–25, A/72/439/Add.3, archived from the original on 23 October 2018, retrieved 22 October 2018 - ^ "Doc. 14506 (Report) State of emergency: proportionality issues concerning derogations under Article 15 of the European Convention on Human Rights – PACE resolution". assembly.coe.int. Archived from the original on 28 April 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ^ "PACE urges Russia to stop supplying arms to Donbas". www.ukrinform.net. 26 April 2018. Archived from the original on 30 April 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ^ "Aryev explains why PACE resolution is important for Ukraine". www.ukrinform.net. 25 April 2018. Archived from the original on 30 April 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ^ "General Assembly resolution demands end to Russian offensive in Ukraine". UN News. 2 March 2022. Retrieved 26 August 2022.