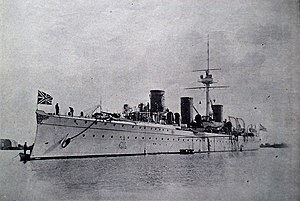

Novík (Russian: Новик) was a protected cruiser in the Imperial Russian Navy, built by Schichau shipyards in Elbing near Danzig, Germany.

Novik

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Novik |

| Ordered | 1898 |

| Builder | Schichau shipyards, Germany |

| Laid down | February 1900 |

| Launched | 2 August 1900 |

| Commissioned | 3 May 1901 |

| Fate | Scuttled, 20 August 1904 |

| Name | Suzuya |

| Acquired | by Japan as prize of war, 1904 |

| Fate | Sold for scrap, 1 April 1913 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Protected cruiser |

| Displacement | 3,080 long tons (3,129 t) |

| Length | 110 m (360 ft 11 in) w/l |

| Beam | 12.2 m (40 ft) |

| Draught | 5 m (16 ft 5 in) |

| Installed power | 12 boilers; 18,000 ihp (13,000 kW) |

| Propulsion | 3 shafts; 3 triple-expansion steam engines |

| Speed | 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph) |

| Range |

|

| Complement | 340 |

| Armament | As built:

As Suzuya:

|

| Armour |

|

Background

editNovik was ordered as a part of a program to bolster the Russian Pacific Fleet with a 3000-ton class reconnaissance cruiser. Shipbuilders from several countries offered designs, and eventually the German shipbuilders Schichau-Werke, better known for its torpedo boats was selected. The new cruiser was launched on 2 August 1900 and her trials began on 2 May 1901. Some initial vibration problems were experienced with her screws, but testing was completed on 23 April 1902 with five test runs at an average speed of 25.08 knots. This made Novik one of the fastest cruisers in the world at the time,[1] which so impressed the Russian naval leadership that a near copy was made in the Russian Izumrud class. On 15 May 1902, Novik was assigned to the Russian naval base at Kronstadt.

Service life (Russia)

editEarly career

editOn 14 September 1902, Novik departed Kronstadt for the Pacific, via the Kiel Canal, stopping at Brest (5 October), Cadiz, Naples and Piraeus, where she rendezvoused with the battleship Imperator Nikolai I.[2] She departed Greece for Port Said on 11 December, but was forced to turn back due to severe weather, only transiting the Suez Canal on 20–21 December. Afterwards, she called on Jeddah, Djibouti, Aden, Colombo and Sabang, reaching Singapore on 28 February 1903, Manila, Shanghai and finally arriving at Port Arthur on 2 April 1903.

She was assigned to accompany the cruiser Askold to Japan from 26 to 29 May 1903 on a diplomatic mission, conveying Russian Minister of War Aleksey Kuropatkin to Kobe and Nagasaki, returning to Port Arthur from 12 to 13 June. She was then sent to Vladivostok over overhaul and dry-dock inspection from 23 July. As with other ships in the Pacific Fleet, she received a new dark olive paint scheme. She returned to Port Arthur in early September.

Russo-Japanese War

editNovik suffered minor damage from an 8-inch shell, after she single-handedly pursued the attacking Japanese destroyers for nearly 30 miles on 9 February 1904, during the Battle of Port Arthur.[3][4] Novik's commander, Captain Nikolai von Essen was one of the few ships in the Russian fleet to offer combat, and the only one to pursue the enemy, closing to within 3,000 yards of the Japanese squadron to deliver a torpedo, without effect. Novik's damage required nine days to repair.[5]

On 10 March 1904, Admiral Makarov sortied in Novik as his flagship, from Port Arthur, along with the cruiser Bayan to rescue one his destroyers, then in hot combat with a Japanese destroyer, just outside of shore battery range. After three attempts, withdrawing each time to within shore battery protection, coupled with the arrival of Japanese Armored Cruisers, the Russian destroyer finally sank, and Makarov and Novik returned to Port Arthur.[6][7]

On 13 April 1904, a similar incident occurred, the Torpedo Boat Destroyer Strashni was fighting Japanese Torpedo Boat Destroyers, and was in sinking condition, when the Russian cruiser Bayan showed up, which quickly caused the enemy destroyers to leave the area. But the Bayan also knew that the retreating Japanese destroyers were headed to their own Armored Cruisers. Bayan picked up some survivors, then just outside of Port Arthur met with Admiral Makarov aboard his flagship Petropavlovsk, along with the cruisers Novik, Askold, Diana, and the battleship Poltava just coming out of Port Arthur.[8] Several minutes later the flagship struck three mines just outside the entrance to Port Arthur, and sank with great loss of life (including Admiral Makarov). The fleet then returned to the safe confines of Port Arthur.

On 23 June, Novik was again part of an unsuccessful attempted sortie from Port Arthur, this time under Makarov's successor, Admiral Wilgelm Vitgeft.

On 10 August, the Russian fleet once more attempted to run the Japanese blockade of Port Arthur. In the resulting Battle of the Yellow Sea, most of the Russian ships returned to port but several managed to escape to be interned in various neutral ports. Novik was slightly damaged by three hits and two crewmen were killed. Novik reached the neutral German port of Qingdao ; however, choosing to avoid internment, Commander Mikhail Fedorovich von Schultz chose to outrace its Japanese pursuers around the Japanese home islands towards Vladivostok, hoping to join with the Russian cruiser squadron based there. Novik was pursued by the Japanese cruiser Tsushima, which was later joined by Chitose. Spotted by a Japanese transport ship while coaling at Sakhalin, Novik was trapped in Aniva Bay, and forced into the Battle of Korsakov by Tsushima. Realizing that he was hopelessly outgunned and after sustaining five hits, three of them under the water line, von Schultz ordered Novik scuttled, intending to make salvage impossible.

Service life (Japan)

editThe Imperial Japanese Navy had been impressed with the speed of Novik, and despite the considerable damage inflicted during the Battle of Korsakov (and the damage created by its own crew in attempting to scuttle the vessel), sent an engineering crew to salvage the vessel as a prize of war in August 1905. The operation took almost a year to accomplish. The wreck was repaired at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal, and commissioned in the Imperial Japanese Navy as Suzuya on 20 August 1906. Her new name came from the Suzuya River in Karafuto, near where Novik was captured.

During the repair work, her original boilers were replaced by eight Miyabara boilers, her three smokestacks were reduced to two, her lateral engines were removed and power output was reduced to 6,000HP. Suzuya's bow and stern main guns were replaced with 120-mm guns and her four 120-mm guns amidships were replaced by 76-mm guns. She also retained her six 47mm Hotchkiss guns and two 37mm guns. All repairs were complete by December 1908, and she was officially designated as an aviso rather than as a cruiser. Indeed, she served with the IJN primarily for high speed reconnaissance and as a dispatch vessel; however, due to her battle damage and fewer boilers, the repaired vessel could only attain a maximum speed of 19 knots (35 km/h), as opposed to 25 knots (46 km/h) in her original configuration. Furthermore, the development of wireless communications quickly made such dispatch vessels obsolete. Suzuya was re-classified as a second-class coastal defense vessel on 28 August 1912, and was declared obsolete and sold for scrap on 1 April 1913.

Notes

edit- ^ Article 21 July 1901 New York Times

- ^ French newspaper Patrie, quoted in "Naval & Military intelligence". The Times. No. 36896. London. 11 October 1902. p. 12.

- ^ Steer (1913) p. 16, 17

- ^ Corbett (2015) Vol. 1, p. 98

- ^ [1] Article New York Times

- ^ Steer (1913) p. 50

- ^ Corbett (2015) Vol. 1, p. 150

- ^ Corbett (2015) Vol. 1, p.180-183

References

edit- Campbell, N. J. M. (1979). "Russia". In Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M. (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. New York: Mayflower Books. pp. 170–217. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.

- Corbett, Sir Julian. (2015) Maritime Operations In The Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905. Vol. 1 originally published Jan 1914. Naval Institute Press ISBN 978-1-59114-197-6

- Corbett, Sir Julian. (2015) Maritime Operations In The Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905. Vol. 2 originally published Oct 1915. Naval Institute Press ISBN 978-1-59114-198-3

- Howarth, Stephen. The Fighting Ships of the Rising Sun: The Drama of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1895–1945. Atheneum; (1983) ISBN 0-689-11402-8

- Jentsura, Hansgeorg. Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. Naval Institute Press (1976). ISBN 0-87021-893-X

- Steer, A. P., Lieutenant, Imperial Russian Navy. (1913) The "Novik" And The Part She Played In The Russo-Japanese War, 1904. Translated by L.A.B., translator and editor of "Rasplata." N.Y., E. P. Dutton and Company.