The United States Southern Command (USSOUTHCOM), located in Doral in Greater Miami, Florida, is one of the eleven unified combatant commands in the United States Department of Defense. It is responsible for providing contingency planning, operations, and security cooperation for Central and South America, the Caribbean (except U.S. commonwealths, territories, and possessions), their territorial waters, and for the force protection of U.S. military resources at these locations. USSOUTHCOM is also responsible for ensuring the defense of the Panama Canal and the canal area.[8]

| United States Southern Command | |

|---|---|

| |

| Founded | 11 June 1963 (61 years, 5 months ago) |

| Country | |

| Type | Unified combatant command |

| Role | Geographic combatant command |

| Size | 1,200 personnel[1] |

| Part of | United States Department of Defense |

| Headquarters | Doral, Florida, U.S. |

| Engagements | United States invasion of Grenada Invasion of Panama Operation Uphold Democracy Operation Secure Tomorrow Operation New Horizons Operation Unified Response Operation Continuing Promise |

| Decorations | |

| Website | www.southcom.mil |

| Commanders | |

| Commander | Admiral Alvin Holsey, USN[3] |

| Military Deputy Commander | Lieutenant General Evan L. Pettus, USAF[4] |

| Civilian Deputy to the Commander | Ambassador Sarah-Ann Lynch, DOS[5] |

| Insignia | |

| Distinctive Unit Insignia |  |

| NATO Map Symbol[6][7] |  |

| Unit Flag |  |

Under the leadership of a four-star Commander, USSOUTHCOM is organized into a headquarters with six main directorates, component commands and military groups that represent SOUTHCOM in the region. USSOUTHCOM is a joint command[9] of more than 1,201 military and civilian personnel representing the United States Army, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, Marine Corps, Coast Guard, and several other federal agencies. Civilians working at USSOUTHCOM are, for the most part, civilian employees of the Army, as the Army is USSOUTHCOM's Combatant Command Support Agent. The Services provide USSOUTHCOM with component commands which, along with their Joint Special Operations component, two Joint Task Forces, one Joint Interagency Task Force, and Security Cooperation Offices, perform USSOUTHCOM missions and security cooperation activities. USSOUTHCOM exercises its authority through the commanders of its components, Joint Task Forces/Joint Interagency Task Force, and Security Cooperation Organizations.

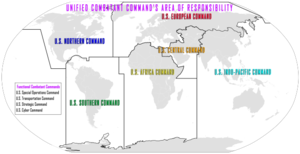

Area of Responsibility

editThe USSOUTHCOM Area of Responsibility (AOR) encompasses 32 nations (19 in Central and South America and 13 in the Caribbean), of which 31 are democracies, and 14 U.S. and European territories. As of October 2002, the area of focus covered 14.5 million square miles (23.2 million square kilometers.)[10]

The United States Southern Command area of interest includes:

- The land mass of Latin America south of Mexico

- The waters adjacent to Central and South America

- The Caribbean Sea, its 12 island nations and European territories

- A portion of the Atlantic Ocean

Components

editUSSOUTHCOM accomplishes much of its mission through its service components, four representing each service, one specializing in Special Operations missions, and three additional joint task forces:[11]

U.S. Army South (Sixth Army)

editUnited States Army South (ARSOUTH) forces include aviation, intelligence, communication, and logistics units. Located at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, it supports regional disaster relief and counter-drug efforts. ARSOUTH also exercises oversight, planning, and logistical support for humanitarian and civic assistance projects throughout the region in support of the USSOUTHCOM Theater Security Cooperation Strategy. ARSOUTH provides Title 10 and Executive Agent responsibilities throughout the Latin American and Caribbean region. In 2013, around four thousand troops were deployed in Latin America.[12]

Air Forces Southern (Twelfth Air Force)

editLocated at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, Arizona, AFSOUTH consists of a staff; a Falconer Combined Air and Space Operations Center for command and control of air activity in the USSOUTHCOM area and an Air Force operations group responsible for Air Force forces in the area. AFSOUTH serves as the executive agent for forward operating locations; provides joint/combined radar surveillance architecture oversight; provides intra-theater airlift; and supports USSOUTHCOM's Theater Security Cooperation Strategy through regional disaster relief exercises and counter-drug operations. AFSOUTH also provides oversight, planning, execution, and logistical support for humanitarians and civic assistance projects and hosts a number of Airmen-to-Airmen conferences. Twelfth Air Force is also leading the way in bringing the Chief of Staff of the Air Force's Warfighting Headquarters (WFHQ) concept to life. The WFHQ is composed of a command and control element, an Air Force forces staff and an Air Operations Center. Operating as a WFHQ since June 2004, Twelfth Air Force has served as the Air Force model for the future of Combined Air and Space Operations Centers and WFHQ Air Force forces.

U.S. Naval Forces Southern Command & U.S. Fourth Fleet

editLocated at Naval Station Mayport, Florida, USNAVSO exercises command and control over all U.S. naval operations in the USSOUTHCOM area including naval exercises, maritime operations, and port visits. USNAVSO is also the executive agent for the operation of the cooperative security location at Comalapa, El Salvador, which provides basing in support of aerial counter-narcoterrorism operations.

On 24 April 2008, Admiral Gary Roughead, the Chief of Naval Operations, announced that the United States Fourth Fleet would be re-established, effective 1 July, responsible for U.S. Navy ships, aircraft and submarines operating in the Caribbean Sea, as well as Central and South America. Rear Admiral Joseph D. Kernan was named as the fleet commander and Commander, U.S. Naval Forces Southern Command.[13] Up to four ships are deployed in the waters in and around Latin American, at any given time.[12]

U.S. Marine Corps Forces, South

editLocated in Doral, Florida, USMARFORSOUTH commands all United States Marine Corps Forces (MARFORs) assigned to USSOUTHCOM; advises USSOUTHCOM on the proper employment and support of MARFORs; conducts deployment/redeployment planning and execution of assigned/attached MARFORs; and accomplishes other operational missions as assigned.

Special Operations Command South

editLocated at Homestead Air Reserve Base near Miami, Florida, Special Operations Command South (SOCSOUTH) provides the primary theater contingency response force and plans, prepares for, and conducts special operations in support of USSOUTHCOM. USSOCSOUTH controls all Special Operations Forces in the region and also establishes and operates a Joint Special Operations Task Force when required. As a Theater Special Operations Command (TSOC), USSOCSOUTH is a sub-unified command of USSOUTHCOM.

SOCSOUTH has five assigned or attached subordinate commands including "Charlie" Company, 3rd Battalion, 7th Special Forces Group (Airborne) (7th SFG(A)); "Charlie" Company, 3rd Battalion, 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (Airborne); Naval Special Warfare Unit FOUR; 112th Signal Detachment SOCSOUTH; and Joint Special Operations Air Component-South.

There are also three task forces with specific missions in the region that report to U.S. Southern Command:

Joint Task Force Bravo

editLocated at Soto Cano Air Base, Honduras, Joint Task Force (JTF) -Bravo operates a forward, all-weather day/night C-5-capable airbase. JTF – Bravo organizes multilateral exercises and supports, in cooperation with partner nations, humanitarian and civic assistance, counter-drug, contingency and disaster relief operations in Central America.

Joint Task Force Guantanamo

editLocated at U.S. Naval Station Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, JTF – Guantanamo conducts detention and interrogation operations in support of the War on Terrorism, coordinates and implements detainee screening operations, and supports law enforcement and war crimes investigations as well as Military Commissions for Detained Enemy Combatants. JTF – Guantanamo is also prepared to support mass migration operations at Naval Station GTMO.

Joint Interagency Task Force South

editLocated in Key West, Florida, JIATF South is an interagency task force that serves as the catalyst for integrated and synchronized interagency counter-drug operations and is responsible for the detection and monitoring of suspect air and maritime drug activity in the Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico, and the eastern Pacific. JIATF- South also collects, processes, and disseminates counter-drug information for interagency operations. Manta Air Base was one of JIATF-South's bases, in Ecuador until 19 September 2009.[14]

Humanitarian assistance and disaster relief

editUSSOUTHCOM's overseas humanitarian assistance and disaster relief programs build the capacity of host nations to respond to disasters and build their self-sufficiency while also empowering regional organizations.

These programs provide valuable training to U.S. military units in responding effectively to assist the victims of storms, earthquakes, and other natural disasters through the provision of medical, surgical, dental, and veterinary services, as well as civil construction projects.

The Humanitarian Assistance Program funds projects that enhance the capacity of host nations to respond when disasters strike and better prepare them to mitigate acts of terrorism. Humanitarian Assistance Program projects such as technical aid and the construction of disaster relief warehouses, emergency operation centers, shelters, and schools promote peace and stability, support the development of the civilian infrastructure necessary for economic and social reforms, and improve the living conditions of impoverished regions in the AOR.

Humanitarian assistance exercises such as Exercise Nuevos Horizontes (New Horizons) involve the construction of schools, clinics, and water wells in countries throughout the region. At the same time, medical readiness exercises involving teams consisting of doctors, nurses and dentists also provide general and specialized health services to host nation citizens requiring care. These humanitarian assistance exercises, which last several months each, provide much-needed services and infrastructure, while providing critical training for deployed U.S. military forces. These exercises generally take place in rural, underprivileged areas. USSOUTHCOM attempts to combine these efforts with those of host-nation doctors, either military or civilian, to make them even more beneficial.

In 2006, USSOUTHCOM sponsored 69 Medical Readiness Training Exercises in 15 nations, providing medical services to more than 270,000 citizens from the region. During 2007, USSOUTHCOM is scheduled to conduct 61 additional medical exercises in 14 partner nations.

USSOUTHCOM sponsors disaster preparedness exercises, seminars and conferences to improve the collective ability of the U.S. and its partner nations to respond effectively and expeditiously to disasters. USSOUTHCOM has also supported the construction or improvement of three Emergency Operations Centers, 13 Disaster Relief Warehouses and prepositioned relief supplies across the region. Construction of eight additional Emergency Operation Centers and seven additional warehouses is ongoing.

This type of multinational disaster preparedness has proven to increase the ability of USSOUTHCOM to work with America's partner nations. For example, following the 2005 Hurricane Stan in Guatemala, USSOUTHCOM deployed 11 military helicopters and 125 personnel to assist with relief efforts. In conjunction with their Guatemalan counterparts, they evacuated 48 victims and delivered nearly 200 tons of food, medical supplies and communications equipment. Following Tropical Storm Gamma in Honduras, JTF-Bravo deployed nine helicopters and more than 40 personnel to assist with relief efforts. They airlifted more than 100,000 pounds of emergency food, water and medical supplies. USSOUTHCOM was deployed to Haiti following the 2010 Haiti earthquake to lead the humanitarian effort.[15]

USSOUTHCOM also conducts counter-narcotics and counter-narcoterrorism programs.

History

editThe United States Southern Command (USSOUTHCOM) traces its origins to 1903 when the first U.S. Marines arrived in Panama to ensure U.S. control of the Panama Railroad connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans across the narrow waist of the Panamanian Isthmus.[16][17]

The Marines protected the Panamanian civilian uprising against the government of Colombia led by former Panama Canal Company general manager Philippe-Jean Bunau-Varilla, thereby guaranteeing the separation of Panama from Colombia and his creation of the Panamanian state. Following the signing of the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty granting control of the Panama Canal Zone to the United States, the Marines remained to provide security during the early construction days of the Panama Canal.[16]

In 1904, Army Colonel William C. Gorgas was sent to the Canal Zone (as it was then called) as chief sanitary officer to fight yellow fever and malaria. In two years, yellow fever was eliminated from the Canal Zone. Soon after, malaria was also brought under control. With the appointment of Army Lieutenant Colonel George W. Goethals to the post of chief engineer of the Isthmian Canal Commission by then President Theodore Roosevelt in 1907, the construction changed from a civilian to a military project.[16]

In 1911, the first troops of the U.S. Army's 10th Infantry Regiment arrived at Camp E. S. Otis, on the Pacific side of the Isthmus. They assumed primary responsibility for Canal defense. In 1914, the Marine Battalion left the Isthmus to participate in operations against Pancho Villa in Mexico. On 14 August 1914, seven years after Goethals' arrival, the Panama Canal opened to world commerce.[16]

The first company of coast artillery troops arrived in 1914 and later established fortifications at each end (Atlantic and Pacific) of the Canal as the Harbor Defenses (HD) of Cristobal and HD Balboa, respectively, with mobile forces of infantry and light artillery centrally located to support either end. By 1915, a consolidated command was designated as Headquarters, U.S. Troops, Panama Canal Zone. The command reported directly to the Army's Eastern Department headquartered at Fort Jay, Governors Island, New York. The headquarters of this newly created command was first located in the Isthmian Canal Commission building in the town of Ancon, adjacent to Panama City. It relocated in 1916 to the nearby newly designated military post of Quarry Heights, which had begun construction in 1911.[16]

On 1 July 1917, almost three months after the American entry into World War I, the Panama Canal Department was activated as a geographic command of the U.S. Army. It remained as the senior Army headquarters in the region until activation of the Caribbean Defense Command (CDC) on 10 February 1941. The CDC, co-located at Quarry Heights, was commanded by Lieutenant General Daniel Van Voorhis, who continued to command the Panama Canal Department.[16]

The new command eventually assumed operational responsibility over air and naval forces assigned in its area of operations during World War II, which included all U.S. forces and bases in the Caribbean basin outside the continental United States. By early 1942, a Joint Operations Center had been established at Quarry Heights. Meanwhile, 960 jungle-trained officers and enlisted men from the CDC deployed to New Caledonia in the southwest Pacific to help form the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional), codenamed 'Galahad' and later nicknamed Merrill's Marauders for its famous exploits in Burma.[18] In the meantime, military strength in the area was gradually rising and reached its peak in January 1943, when 68,000 personnel were defending the Panama Canal. Military strength was sharply reduced with the termination of World War II. Between 1946 and 1974, total military strength in Panama fluctuated between 6,600 and 20,300 (with the lowest force strength in 1959).

In December 1946, President Harry S. Truman approved recommendations of the Joint Chiefs of Staff for a comprehensive system of military commands to put responsibility for conducting military operations of all military forces in various geographical areas, in the hands of a single commander. Although the Caribbean Command was designated by the Defense Department on 1 November 1947, it did not become fully operational until 10 March 1948, when the old Caribbean Defense Command was inactivated.[16]

On 6 June 1963, reflecting the fact that the command had a responsibility for U.S. military operations primarily in Central and South America, rather than in the Caribbean, President John F. Kennedy and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara formally redesignated it as the United States Southern Command.[16] The command's mission began to shift with the expansion of the Cold War to Latin America. Kennedy and his successor Lyndon B. Johnson expanded the division in the aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis and reoriented it towards irregular warfare against the establishment of another Communist state in the Western Hemisphere.[19] From 1975 until late 1994 total military strength in Panama remained at about 10,000 personnel.[16]

In January 1996 and June 1997, two phases of changes to the Department of Defense Unified Command Plan (UCP) were completed. Each phase of the UCP change added territory to SOUTHCOM's area of responsibility. The impact of the changes is significant. The new AOR includes the Caribbean, its 13 island nations and several U.S. and European territories, the Gulf of Mexico, as well as significant portions of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The 1999 update to the UCP also transferred responsibility of an additional portion of the Atlantic Ocean to SOUTHCOM. On 1 October 2000, Southern Command assumed responsibility of the adjacent waters in the upper quadrant above Brazil, which was presently under the responsibility of U.S. Joint Forces Command.[16]

The new AOR encompasses 32 nations (19 in Central and South America and 13 in the Caribbean), of which 31 are democracies, and 14 U.S. and European territories covering more than 15,600,000 square miles (40,000,000 km2).[16]

With the creation of the United States Department of Homeland Security, USSOUTHCOM Area of Responsibility (October 2002) experienced minor upper boundary redistribution or changes decreasing its total boundary by 1.1 square miles. (14.5 million square miles (23.2 million square kilometers.)

With the implementation of the Panama Canal Treaties (the Panama Canal Treaty of 1977 and the Treaty concerning the Permanent Neutrality and Operations of the Panama Canal), the U.S. Southern Command was relocated in Miami, Florida, on 26 September 1997.[16]

A new headquarters building was constructed and opened in 2010 adjacent to the old rented building in the Doral area of Miami-Dade County. The complex features state-of-the-art planning and conference facilities. This capability is showcased in the 45,000-square-foot Conference Center of the Americas, which can support meetings of differing classification levels and multiple translations, information sources and video conferencing.

In 2012, as many as a dozen SouthCom service members, together with a number of Secret Service officers, were disciplined after they were found to have brought prostitutes to their rooms shortly before President Obama arrived for a summit in Cartagena, Colombia. According to the Associated Press seven Army soldiers and two Marines received administrative punishments for what an official report cited by the wire service said was misconduct consisting "almost exclusively of patronizing prostitutes and adultery." Hiring prostitutes, the report added, "is a violation of the U.S. military code of justice."[20] In 2014, SouthCom commander Kelly testified that while border security was an 'Existential' threat to the country, due to Budget sequestration in 2013 his forces were unable to respond to 75% of illicit trafficking events.[21]

USSOUTHCOM's 2017-2027 Theater Strategy states that potential challenges in the future include transregional and transnational threat networks (T3Ns) which include traditional criminal organizations, as well as the expanding potential of extremist organizations such as ISIL and Hezbollah operating in the region by taking advantage of weak Caribbean and Latin American institutions. USSOUTHCOM also notes that the region is "extremely vulnerable to natural disasters and the outbreak of infectious diseases" due to issues with governance and inequality. Finally, the report recognizes the growing presence of China, Iran and Russia in the region, and that the intentions of these nations bring "a challenge to every nation that values nonaggression, rule of law, and respect for human rights". These challenges have been used to promote relationships between the United States and other governments in the region.[22]

State Partnership Program

editUS SOUTHCOM currently has 22 state partnerships under the state partnership program (SPP). SPP creates a partnership between a state of the U.S. and a foreign nation by linking the host nation military or security forces with the National Guard. SOUTHCOM is equaled only by EUCOM in its number of partnerships.

Commanders

editThe U.S. Southern Command was activated in 1963, emerging from the U.S. Caribbean Command, established in 1947. Last commander of the U.S. Caribbean Command from January 1961 to June 1963 and first commander of the U.S. Southern Command since June 1963 was Lieutenant General–later General–Andrew P. O'Meara.[23]

| No. | Commander | Term | Service branch | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portrait | Name | Took office | Left office | Term length | ||

| 1 | Lieutenant General Willis D. Crittenberger (1890–1980) | November 1947 | June 1948 | ~ 213 days | U.S. Army | |

| 2 | Lieutenant General Matthew B. Ridgway (1895–1993) | June 1948 | October 1949 | ~ 1 year, 122 days | U.S. Army | |

| 3 | Lieutenant General William H. H. Morris Jr. (1890–1971) | October 1949 | April 1952 | ~ 2 years, 183 days | U.S. Army | |

| 4 | Lieutenant General Horace L. McBride (1894–1962) | April 1952 | June 1954 | ~ 2 years, 61 days | U.S. Army | |

| 5 | Lieutenant General William K. Harrison Jr. (1895–1987) | June 1954 | January 1957 | ~ 2 years, 214 days | U.S. Army | |

| 6 | Lieutenant General Robert M. Montague (1899–1958) | January 1957 | February 1958 | ~ 1 year, 31 days | U.S. Army | |

| 7 | Lieutenant General Ridgely Gaither (1903–1992) | April 1958 | July 1960 | ~ 2 years, 91 days | U.S. Army | |

| 8 | Lieutenant General Robert F. Sink (1905–1965) | July 1960 | January 1961 | ~ 184 days | U.S. Army | |

| 9 | General Andrew P. O'Meara (1907–2005) | 6 January 1961 | 22 February 1965 | 4 years, 47 days | U.S. Army | |

| 10 | General Robert W. Porter Jr. (1908–2000) | 22 February 1965 | 18 February 1969 | 3 years, 362 days | U.S. Army | |

| 11 | General George R. Mather (1911–1993) | 18 February 1969 | 20 September 1971 | 2 years, 214 days | U.S. Army | |

| 12 | General George V. Underwood Jr. (1913–1984) | 20 September 1971 | 17 January 1973 | 1 year, 119 days | U.S. Army | |

| 13 | General William B. Rosson (1918–2004) | 17 January 1973 | 1 August 1975 | 2 years, 196 days | U.S. Army | |

| 14 | Lieutenant General Dennis P. McAuliffe | 1 August 1975 | 1 October 1979 | 4 years, 61 days | U.S. Army | |

| 15 | Lieutenant General Wallace H. Nutting (1928–2023) | 1 October 1979 | 24 May 1983 | 3 years, 235 days | U.S. Army | |

| 16 | General Paul F. Gorman (born 1927) | 24 May 1983 | 1 March 1985 | 1 year, 281 days | U.S. Army | |

| 17 | General John R. Galvin (1929–2015) | 1 March 1985 | 6 June 1987 | 2 years, 97 days | U.S. Army | |

| 18 | General Frederick F. Woerner Jr. (1933–2023) | 6 June 1987 | 1 October 1989 | 2 years, 117 days | U.S. Army | |

| 19 | General Maxwell R. Thurman (1931–1995) | 1 October 1989 | 21 November 1990 | 1 year, 51 days | U.S. Army | |

| 20 | General George A. Joulwan (born 1939) | 21 November 1990 | October 1993 | ~ 2 years, 314 days | U.S. Army | |

| - | Major General Walter T. Worthington Acting | October 1993 | 17 February 1994 | ~ 139 days | U.S. Air Force | |

| 21 | General Barry McCaffrey (born 1942) | 17 February 1994 | 1 March 1996 | 2 years, 13 days | U.S. Army | |

| - | Rear Admiral James Perkins Acting | 1 March 1996 | 26 June 1996 | 117 days | U.S. Navy | |

| 22 | General Wesley Clark (born 1944) | 26 June 1996 | 13 July 1997 | 1 year, 17 days | U.S. Army | |

| - | Rear Admiral Walter F. Doran (born 1945) Acting | 13 July 1997 | 25 September 1997 | 74 days | U.S. Navy | |

| 23 | General Charles E. Wilhelm (born 1941) | 25 September 1997 | 8 September 2000 | 2 years, 349 days | U.S. Marine Corps | |

| 24 | General Peter Pace (born 1945) | 8 September 2000 | 30 September 2001 | 1 year, 22 days | U.S. Marine Corps | |

| - | Major General Gary D. Speer Acting | 30 September 2001 | 18 August 2002 | 322 days | U.S. Army | |

| 25 | General James T. Hill (born 1946) | 18 August 2002 | 9 November 2004 | 2 years, 83 days | U.S. Army | |

| 26 | General Bantz J. Craddock (born 1949) | 9 November 2004 | 19 October 2006 | 1 year, 344 days | U.S. Army | |

| 27 | Admiral James G. Stavridis (born 1955) | 19 October 2006 | 25 June 2009 | 2 years, 249 days | U.S. Navy | |

| 28 | General Douglas M. Fraser (born 1953) | 25 June 2009 | 19 November 2012 | 3 years, 147 days | U.S. Air Force | |

| 29 | General John F. Kelly (born 1950) | 19 November 2012 | 14 January 2016 | 3 years, 56 days | U.S. Marine Corps | |

| 30 | Admiral Kurt W. Tidd (born 1956) | 14 January 2016 | 26 November 2018 | 2 years, 316 days | U.S. Navy | |

| 31 | Admiral Craig S. Faller (born 1961) | 26 November 2018 | 29 October 2021 | 2 years, 337 days | U.S. Navy | |

| 32 | General Laura J. Richardson (born 1963) | 29 October 2021 | 7 November 2024 | 3 years, 9 days | U.S. Army | |

| 33 | Admiral Alvin Holsey (born 1965) | 7 November 2024 | Incumbent | 15 days | U.S. Navy | |

See also

edit- Caribbean Regional Maritime Agreement

- Manta Air Base

- Operation Coronet Nighthawk

- Operation Enduring Freedom - Caribbean and Central America

- Partnership for Prosperity and Security in the Caribbean

- Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (formerly School of the Americas)

- Naval Base Panama Canal Zone

References

edit- ^ "About USSOUTHCOM". U.S. Southern Command. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ Colombian President Visits, Thanks Southcom for its Support, DoD, dated 2018, last accessed 25 April 2018

- ^ "Adm. Alvin Holsey". U.S. Southern Command. Retrieved 8 November 2024.

- ^ "Lt. Gen. Evan L. Pettus". U.S. Southern Command. Retrieved 8 November 2024.

- ^ "Amb. Sarah-Ann Lynch". U.S. Southern Command. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ FM 1-02 Operational Terms and Graphics (PDF). US Army. 21 September 2004. pp. 5–36.

- ^ ADP 1-02 Terms and Military Symbols (PDF). US Army. 14 August 2018. pp. 4–8.

- ^ "About Us". U.S. Southern Command. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ See TITLE 10 > Subtitle A > PART I > CHAPTER 6 > § 164 for assignment, powers and duties.

- ^ [1] Archived 14 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "SOUTHCOM Component Commands & Units". U.S. Southern Command. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ a b martha Mendoza (3 February 2013). "Military expands its drug war in Latin America". Army Times. Associated Press. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ^ "News Release View - Navy Re-Establishes U.S. Fourth Fleet – DOD New Release No. 338-07 – 24 April 2008". Defenselink.mil. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ "Last US forces abandon Manta military base in Ecuador". DEn.mercopress.com. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ [2] Archived 17 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "U.S. Southern Command History". USSOUTHCOM. 11 September 2006. Archived from the original on 17 October 2008. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ U.S. Army South – A Brief History

- ^ "MERRILL'S MARAUDERS ASSOCIATION WELCOME PAGE". www.marauder.org.

- ^ Collins, N.W. (2021). Grey wars : a contemporary history of U.S. special operations. New Haven. ISBN 978-0-300-25834-9. OCLC 1255527666.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Report: Colombian prostitute scandal involved military". Content.usatoday.com. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ O'Toole, Molly (5 July 2014). "Top General Says Mexico Border Security Now 'Existential' Threat to U.S." Defenseone.com. National Journal Group, Inc. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ "2017-2027 Theater Strategy" (PDF). USSOUTHCOM. 4 April 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 June 2017. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- ^ "A Half-Century of Service SOUTHCOM" (PDF). USSOUTHCOM. 2013. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

Further reading

edit- Conn, Stetson; Engelman, Rose C.; Fairchild, Byron (2000) [1964], Guarding the United States and its Outposts, United States Army in World War II, Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army

- Vasquez, Cesar A. "A History of the United States Caribbean Defense Command (1941-1947)." Florida International University, doctoral thesis (2016).

External links

edit- Official website

- Latin, Caribbean allies hail new U.S. Southern Command chief by John Yearwood, Miami Herald, 26 June 2009