Super Smash Bros.[a] is a 1999 crossover fighting game developed by HAL Laboratory and published by Nintendo for the Nintendo 64. It is first game in the Super Smash Bros. series and was released in Japan on January 21, 1999; in North America on April 26, 1999;[1][2] and in Europe on November 19, 1999.

| Super Smash Bros. | |

|---|---|

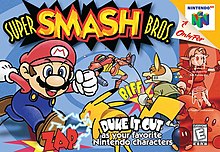

North American box art | |

| Developer(s) | HAL Laboratory |

| Publisher(s) | Nintendo |

| Director(s) | Masahiro Sakurai |

| Producer(s) |

|

| Programmer(s) | Yoshiki Suzuki |

| Artist(s) | Tsuyoshi Wakayama |

| Composer(s) | Hirokazu Ando |

| Series | Super Smash Bros. |

| Platform(s) | Nintendo 64, iQue Player |

| Release | Nintendo 64iQue Player

|

| Genre(s) | Fighting |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, multiplayer |

The game is a crossover among different Nintendo franchises, including Mario, The Legend of Zelda, Star Fox, Yoshi, Donkey Kong, Metroid, F-Zero, Mother, Kirby, and Pokémon. It presents a cast of characters and locations from these franchises and allows players to use each character's unique skills and the stage's hazards to inflict damage, recover health, and ultimately knock opponents off the stage.

Super Smash Bros. received generally positive reviews upon its release. It was a commercial success, selling over five million copies worldwide by 2001,[3] with 2.93 million sold in the United States and 1.97 million sold in Japan.[4][5] It was given an Editors' Choice award from IGN for the "Best Fighting Game",[6] and also became a Nintendo 64 Player's Choice title. The game spawned a series of sequels for each successive Nintendo console, starting with Super Smash Bros. Melee, which was released for the GameCube in 2001.

Gameplay

editThe Super Smash Bros. series is a departure from the general genre of fighting games; instead of depleting an opponent's life bar, Smash Bros. players seek to knock opposing characters off a stage.[7] Each player has a damage total, represented by a percentage, which rises as the damage is taken.[8] As this percentage rises, the character is knocked progressively farther by attacks.[6] To knock out (KO) an opponent, the player must send that character flying off the edge of the stage, which is not an enclosed arena but rather an area with open boundaries.[9] When knocked off the stage, a character may use jumping moves in an attempt to return; some characters have longer-ranged jumps and may have an easier time "recovering" than others.[10]

While games such as Street Fighter and Tekken require players to memorize complicated button-input combinations, Super Smash Bros. uses the same control combinations to access all moves for all characters.[6] Characters are additionally not limited to only facing opponents, instead being allowed to move freely. The game focuses more on aerial and platforming skills than other fighting games, with larger, more dynamic stages rather than a simple flat platform. Smash Bros. also implements blocking and dodging mechanics. Grabbing and throwing other characters is also possible. Support for the Nintendo 64 Rumble Pak is included.[11]

Various weapons and power-ups can be used in battle to inflict damage, recover health, or dispense additional items.[6] They fall randomly onto the stage in the form of items from Nintendo franchises, such as Koopa shells, hammers, and Poké Balls.[12] The nine multiplayer stages are locations taken from or in the style of Nintendo franchises, such as Planet Zebes from Metroid and Sector Z from Star Fox.[11] Although stages are rendered in three dimensions, players move within a two-dimensional plane. Stages are dynamic, ranging from simple moving platforms to dramatic alterations of the entire stage. Each stage offers unique gameplay and strategic motives, making the chosen stage an additional factor in the fight.

In the game's single-player mode, the player battles a series of computer-controlled opponents in a specific order, attempting to defeat them with a limited number of lives in a limited amount of time. While the player can determine the difficulty level and the number of lives, the series of opponents never changes. If the player loses all of their lives or runs out of time, they can continue at the cost of a loss of overall points. This mode is referred to as Classic Mode in later games.[13] The single-player mode also includes two minigames, "Break the Targets" and "Board the Platforms", in which the objective is to break each target or board multiple special platforms, respectively. A "Training Mode" is also available in which players can manipulate the environment and experiment against computer opponents without the restrictions of a standard match.

Up to four people can play in multiplayer mode, which has specific rules predetermined by the players. Stock and timed matches are two of the multiplayer modes of play.[7] This gives each player a certain number of lives or a selected time limit, before beginning the match with a countdown. Free-for-all or team battles are also a choice during matches using stock or time. A winner is declared once time runs out, or if all players except one or a team have lost all of their lives. A multiplayer game may also end in a tie if two or more players have the same score when the timer expires, which causes the match to end in sudden death. During sudden death, all fighters are given 300% damage and the last fighter standing will win the match.

Characters

editThe game includes twelve playable characters from popular Nintendo franchises.[14] Characters have a symbol appearing behind their damage meter corresponding to the series to which they belong, such as a Triforce behind Link's and a Poké Ball behind Pikachu's. Furthermore, characters have recognizable moves derived from their original series, such as Samus's charged blasters and Link's arsenal of weapons.[15] Eight characters are initially playable, and four additional characters can be unlocked by meeting specific criteria.

The character art featured on the game's box art and instruction manual is in the style of a comic book, and the characters are portrayed as toy dolls that come to life to fight. This style has since been omitted in later games, which feature trophies instead of dolls and in-game models rather than hand-drawn art.[16]

Development

editSuper Smash Bros. was developed by HAL Laboratory, a Nintendo second-party developer, during 1998. Masahiro Sakurai was interested in making a fighting game for four players. He made a presentation of what was then called Dragon King: The Fighting Game (格闘ゲーム竜王, Kakutō Gēmu Ryūō)[17][18] to co-worker Satoru Iwata, who joined to help on the project. At this stage in development, the game was still using placeholder character models. Sakurai understood that many fighting games did not sell well and that he had to think of a way to make his game original.[17]

His first idea was to include famous Nintendo characters and put them in a fight.[17] Knowing that he would not get permission if he asked ahead of time, Sakurai made a prototype of the game without informing Nintendo, and did not show anyone until it was well-balanced.[17] The prototype he presented featured Mario, Donkey Kong, Samus and Fox as playable characters.[19] The idea was later approved.[17][20] Although never acknowledged by Nintendo or any developers behind Super Smash Bros., third-party sources have identified Namco's 1995 fighting game The Outfoxies as a possible inspiration,[21][22][23] with Sakurai also crediting the idea of making a beginner-friendly fighting game to an experience in which he handily defeated a couple of casual gamers on The King of Fighters '95 in an arcade.[24] According to Sakurai, the title came from Satoru Iwata when they were considering different names for the title; Iwata suggested the use of "brothers" (shorten to "Bros."), as, according to Sakurai, "his reasoning was that, even though the characters weren't brothers at all, using the word added the nuance that they weren't simply fighting – they were friends who were settling a little disagreement."[25]

On October 20, 2022, Sakurai, who still had the prototype of Dragon King: The Fighting Game, demonstrated its gameplay and its differences from the final product of Super Smash Bros.[26] Multiple planned characters were cut during development, including Marth, King Dedede, Bowser, and Mewtwo; all four of these characters were added to later games.[27]

Music

editSuper Smash Bros. features music from some of Nintendo's popular gaming franchises. While many are newly arranged for the game, some pieces are taken directly from their sources. The music for Super Smash Bros. was composed by Hirokazu Ando, who later returned as sound and music director for Super Smash Bros. Melee. A complete soundtrack was released on CD in Japan through Teichiku Records in 2000.[28]

Release

editThe game was revealed as early as November 1998[29][30][31] and plans for a North American release were revealed in February 1999.[32] To promote the game's launch, Nintendo of America staged an event called Slamfest '99, held at the MGM Grand Adventures theme park in Las Vegas, Nevada, on April 24, 1999.[33] The event featured a real-life wrestling match between costumed performers dressed as Mario, Yoshi, Pikachu, and Donkey Kong, as well as stations set up for attendees to preview the game.[33] The costumes were re-used from the game's television commercial, which featured the four mascot costumes fighting each other set to "Happy Together" by The Turtles.[34][35] The wrestling match was live-streamed on the web via RealPlayer, and was available to be re-watched for several months afterward via a downloadable file from the event's official website.[36] Despite this, no video footage of Slamfest '99 is known to survive, and the broadcast is currently considered lost media.

Reception

edit| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| GameRankings | 79%[37] |

| Metacritic | 79/100[38] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| AllGame | [11] |

| Electronic Gaming Monthly | 8.625/10[b] |

| EP Daily | 2/10[40] |

| Famitsu | 31/40[41][42] |

| Game Informer | 8.5/10[43] |

| GameRevolution | B[44] |

| GameSpot | 7.5/10[7] |

| IGN | 8.5/10[6] |

| Jeuxvideo.com | 16/20[45] |

| N64 Magazine | 90%[46] |

| Next Generation | [47] |

| Nintendo Power | 7.7/10[48] |

| Publication | Award |

|---|---|

| IGN | Best Fighting Game |

Upon its initial Nintendo 64 release, Super Smash Bros. received "generally favorable" reviews according to review aggregator site Metacritic, based on 11 reviews.[38] Its score on Metacritic matches that of GameRankings at 79%.[37] Critical praise was directed towards its multiplayer mode,[7][6][11][8] music,[7] "original" fighting game style,[8] and simple learning curve.[7][11] IGN highlighted the game's multiplayer mode, calling it, "an excellent choice for gamers looking for a worthy multiplayer smash 'em-up."[6] GameSpot expressed that the game is "extremely simple to learn and easy to master" and stated that "the game's real charm comes out in four-player mode."[7] Japanese gaming magazine Famitsu rated it a 31 out of 40.[41][42] Comparing it to previous attempts at four-player fighting games, Game Informer remarked that Super Smash Bros. "does a fine job of proving that the more characters onscreen, the better."[43]

IGN criticized the game's battle stage and character offerings as "much too limited" and "routine" in the single-player experience.[6] Despite acclaiming the game's graphical and audio quality, GameCritics.com noted that the fast-paced gameplay presented problems with the scoring system, stating, "It's ridiculous that the number of times you and your opponents are thrown off-stage are not tallied for you and on-screen so you to see."[8] GameSpot's former editorial director, Jeff Gerstmann, noted the single-player game "won't exactly last a long time".[7] Electronic Gaming Monthly held that its "novel concept alone makes this game worth checking out," but that, it "may not be worth the cash" for a single-player experience.[39]

Super Smash Bros. was commercially successful, becoming a Nintendo 64 Player's Choice title, selling 1.97 million copies in Japan[5] and 2.93 million in the United States as of 2008.[4] The Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences named Super Smash Bros. as a finalist for "Console Action Game of the Year" and "Console Fighting Game of the Year" at the 3rd Annual Interactive Achievement Awards.[49]

Notes

edit- ^ Known in Japan as Nintendo All Star! Great Melee Smash Brothers (ニンテンドウオールスター!大乱闘スマッシュブラザーズ, Nintendō Ōru Sutā! Dai Rantō Sumasshu Burazāzu) and retroactively referred to as Super Smash Bros. 64 or Smash 64

- ^ Super Smash Bros., in Electronic Gaming Monthly's review, was scored by three critics 8.5/10, another one 9/10.[39]

References

edit- ^ a b c "Super Smash Bros". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on January 22, 2016. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- ^ a b "Super Smash Bros". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on September 1, 2013. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- ^ JC, Anthony. "Super Smash Bros. Melee". N-Sider.com. Archived from the original on January 23, 2008. Retrieved June 17, 2008.

- ^ a b "US Platinum Game Chart". The-MagicBox.com. Archived from the original on January 6, 2007. Retrieved December 7, 2006.

- ^ a b "Japan Platinum Game Chart". The-MagicBox.com. Archived from the original on December 13, 2007. Retrieved June 17, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Schneider, Peer (April 27, 1999). "Super Smash Bros. Review". IGN. Archived from the original on May 12, 2008. Retrieved April 26, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gerstmann, Jeff (February 18, 1999). "Super Smash Bros. Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved April 26, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Weir, Dale (July 5, 1999). "Game Critics Review". GameCritics.com. Archived from the original on February 25, 2012. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- ^ "The Basic Rules". SmashBros.com. May 22, 2007. Archived from the original on April 13, 2012. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

- ^ "You Must Recover!". SmashBros.com. June 6, 2007. Archived from the original on March 2, 2012. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Penniment, Brad. "Super Smash Bros. > Review". AllGame. Archived from the original on December 1, 2014. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- ^ "Characters". SmashBros.com. Archived from the original on March 18, 2008.

- ^ Sakurai, Masahiro (October 30, 2007). "Classic". SmashBros.com. Archived from the original on April 30, 2008. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ Mirabella III, Fran; Schneider, Peer; Harris, Craig. "Guides: Super Smash Bros. Melee–Characters". IGN. Archived from the original on January 10, 2011. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ^ Mirabella III, Fran; Schneider, Peer; Harris, Craig. "Guides: Super Smash Bros. Melee–Samus Aran". IGN. Archived from the original on January 31, 2009. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ^ Sakurai, Masahiro (September 24, 2007). "Trophies". SmashBros.com. Archived from the original on May 3, 2008. Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e "Iwata Asks: Super Smash Bros. Brawl". IwataAsks.Nintendo.com. Nintendo. Archived from the original on December 17, 2019. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Sakurai, Masahiro (October 20, 2022). Super Smash Bros. Retrieved October 20, 2022 – via YouTube.

- ^ "The Man Who Made Mario Fight". Hobby Consoles (202): 22. 2008.

- ^ "社長が訊く「大乱闘スマッシュブラザーズX」" [Iwata Asks: Super Smash Bros. Brawl]. Nintendo.co.jp (in Japanese). Nintendo. Archived from the original on January 26, 2011. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Burns, Ed (November 22, 2012). "The Outfoxies". HardcoreGaming101.net. Archived from the original on April 22, 2018.

- ^ Holmes, Jonathan (March 3, 2008). "Six Days to Smash Bros. Brawl: Top Five Smash Bros Alternatives". Destructoid. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ Sullivan, Lucas (September 19, 2014). "15 Smash Bros. Rip-Offs That Couldn't Outdo Nintendo". GamesRadar+. Archived from the original on November 15, 2017.

- ^ MacDonald, Keza (August 8, 2018). "From Kong to Kirby: Smash Bros' Masahiro Sakurai on Mashing Up 35 Years of Gaming History". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 20, 2019. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ Gerblick, Jordan (October 11, 2024). "After 25 years, we finally know why it's called Super Smash "Bros" – Nintendo icon Satoru Iwata wanted the fighters to be "friends who were settling a little disagreement"". GamesRadar+. Retrieved October 11, 2024.

- ^ Haughes, Alana (October 20, 2022). "Sakurai Shares First Ever Footage of Dragon King, the N64 Smash Bros. Prototype". NintendoLife.com. Archived from the original on October 28, 2022. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ Soma (April 29, 2016). "The Definitive List of Unused Fighters in Smash". SourceGaming.info. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ "Nintendo All-Star! Dairanto Smash Brothers Original Soundtrack". SoundtrackCentral.com. January 17, 2002. Archived from the original on October 11, 2008. Retrieved April 16, 2008.

- ^ "Who Would Win in a Fight?". IGN. November 9, 1998. Archived from the original on August 17, 2024. Retrieved August 10, 2024.

- ^ "Guess Who's Gonna Kick Mario's Ass?". IGN. November 13, 1998. Archived from the original on August 10, 2024. Retrieved August 10, 2024.

- ^ "大乱闘スマッシュブラザーズ". CoroCoro Comic. Shogakukan. November 15, 1998. p. 43-45.

- ^ "Smash Bros. Gets a US Date". IGN. February 11, 1999. Archived from the original on August 17, 2024. Retrieved August 10, 2024.

- ^ a b IGN Staff (April 22, 1999). "Nintendo Stages Smashing Fight". IGN. Archived from the original on June 4, 2022. Retrieved June 4, 2022.

- ^ Plunkett, Luke (February 14, 2023). "In 1999 Nintendo Had a Real-Life Wrestling Match Starring Mario and Pikachu". Kotaku. Archived from the original on August 17, 2024. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ Van Aken, Alex (July 3, 2023). "Behind the Dangerous Stunts of Nintendo's Iconic Mario Commercials". Game Informer. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ "Smash Bros. Internet Broadcast". Media.InternetBroadcast.com. Archived from the original on September 8, 1999. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ a b "Super Smash Bros. for Nintendo 64". GameRankings. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on December 11, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ a b "Super Smash Bros. for Nintendo 64 Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ^ a b "Super Smash Bros". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 119. June 1999. p. 131. Retrieved July 5, 2021 – via Archive.org.

- ^ Conlin, Shaun. "Super Smash Bros". The Electric Playground. Archived from the original on February 27, 2005. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ a b ニンテンドウ64 - ニンテンドウオールスター!大乱闘スマッシュブラザーズ. Weekly Famitsu. No.915 Pt.2. Pg.32. June 30, 2006.

- ^ a b IGN Staff (November 14, 2001). "Famitsu Scores Smash Bros". IGN. Archived from the original on March 20, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2008.

- ^ a b "Super Smash Bros. Review". Game Informer. Archived from the original on October 7, 2000.

- ^ Dr. Moo. "Super Smash Brothers". GameRevolution. Archived from the original on January 5, 2000. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ Kornifex (December 13, 1999). "Test Super Smash Bros" [Super Smash Bros Test]. Jeuxvideo.com (in French). Archived from the original on May 1, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ Bickham, Jes (May 1999). "Smash Bros". N64 Magazine. No. 28. pp. 74–75. Retrieved July 5, 2021 – via Archive.org.

- ^ "Finals". Next Generation. No. 54. Imagine Media. June 1999. p. 94.

- ^ "Super Smash Bros". Nintendo Power. No. 120. Nintendo of America. May 1999. p. 125 – via Archive.org.

- ^ "Third Interactive Achievement Awards - Console". Interactive.org. Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original on October 11, 2000. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

External links

edit- Official website (Archived March 3, 2005, at the Wayback Machine)

- Super Smash Bros. at MobyGames

- Super Smash Bros. at IMDb