The province of Khuzestan (also spelled Khuzistan; Persian: ولایت خوزستان, romanized: Velāyat-e Khūzestān) was a southwestern province of Safavid Iran, corresponding to the present-day province of Khuzestan.

Safavid Khuzestan Velāyat-e Khūzestān | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1508–1736 | |||||||||

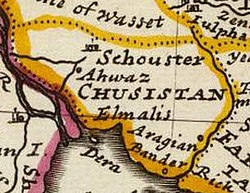

Map of "Chusistan" (Khuzestan), dated 1736 | |||||||||

| Status | Province of Safavid Iran | ||||||||

| Capital | Hoveyzeh | ||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic, Persian | ||||||||

| Government | Velayat | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Name

editThe old name of the province was Khuzestan ("the land of the Khuz"), referring to the ancient Elamites that inhabited the area from the 3rd millennium BC until the rise of the Achaemenid Empire in 539 BC.[1][2] Due to influx of Shi'i Arab tribes invited by the Safavids to act as a bulwark against the Ottoman Empire, the western part of Khuzestan became known as Arabestan.[1] According to the Iranologist Rudi Matthee, this name change took place during the reign of Shah Abbas I (r. 1588–1629).[3][a] Like the provinces of Kurdistan and Lorestan, the name of Arabestan did not have a "national" implication.[1]

Later on, the whole Khuzestan province came to be known as Arabestan. It is uncertain when this change occurred. According to Rudi Matthee, it was first during the reign of the Afsharid ruler Nader Shah (r. 1736–1747), that this happened.[7] The Iranologist Houchang Chehabi considers this to have taken place in the second half of the 18th century.[1] Another Iranologist, Roger Savory, considers this change to have happened later, by the 19th century.[8]

Geography

editKnown for its flat terrain and hot temperature, Khuzestan was unpopular till modern times.[9] It was disconnected to the rest of Iran due its linguistic differences and bad roads.[10] Khuzestan was more important commercially than agriculturally, due to being situated near the Ottoman port town of Basra. The town gave the Ottomans access to the Persian Gulf, and also served as an entrepôt for trade between the Indian Ocean and the Fertile Crescent through Iraq and Syria.[11]

History

editBefore the Safavids, the province was under the control of the Arab Mosha'sha', who used Hoveyzeh as their capital.[12][13] They had initially started out as a tribal confederation, but gradually transformed into a zealous Isma'ili-Shi'i dynasty.[11]

In 1508, the Safavid shah (king) Ismail I (r. 1501–1524), who claimed to be the only legitimate Shi'i ruler, put an end to Mosha'sha' rule in Khuzestan. The Mosha'sha' were further weakened by the death of its ruler Sayyed Mohsen in 1499/1500 or 1508/09. Two of his sons, Ali and Ayyub, attempted to negotiate with Ismail I, but were executed by the latter. The self-determination of the Mosha'sha was finally ruined with the massacre of Sayyed Fayyaz and his supporters in Hoveyzeh. The Iranologist Ahmad Kasravi (died 1946) argues that Sayyed Fayyaz was one the titles of Sayyed Mohsen's son Ali. Nevertheless, Sayyed ibn Sayyed Mohsen soon re-established Mosha'sha' rule in Hoveyzeh, although as a semi-independent ruler. He acknowledged Ismail I as his suzerain.[4]

The Safavids allowed the Mosha'sha' to continue to their rule in the western part of Khuzestan (Arabestan)—on the other side of the Karun River—where Hoveyzeh was also located. In return, they had to pay tribute and give hostages to prove their good behavior. These hostages were either raised at the Safavid court or in a province, such as Sayyed Nasr, who eventually became the governor of Ray and a close friend of the grand vizier, Hatem Beg Ordubadi.[10] Meanwhile, Dezful remained under the control of the Ra'nashi shaykhs, and Shushtar under a local ruler.[4]

Safavid governors of Ahvaz first appear in chronicles in the second half of the 17th century, which suggests that this part of Arabestan was no longer under the direct administration of the Mosha'sha'. During this period, the Mosha'sha' governor of Hoveyzeh was increasingly being referred to as the vali-ye Arabestan, while in the 16th century and early 17th century they had generally been referred to as hakem or vali-ye Hoveyzeh.[10] For a certain period, Arabestan was under the administration of the Fars province. Following the transformation of Fars into khasseh (crown land) in 1632, Arabestan, Shushtar and Dezful came under the jurisdiction of the governor of Kuhgiluyeh for military purposes.[10]

The valis of Hoveyzeh were largely autonomous, and in most of the 16th century took more part in the politics of Khuzestan and southern Iraq than the Safavids themselves. Their involvement in the politics of southern Iraq resulted in a conflict with the Ottoman Empire, who in the 1570s briefly occupied Arabestan, until they were forced to withdraw. Following this, the vali Sayyed Mobarak increased his anti-Ottoman activities, and also tried to increase his autonomy, as the Safavids were occupied with the second "Qizilbash civil war". Shah Abbas I did not accept this behaviour and thus resorted to military means twice against Sayyed Mobarak to keep him in control.[10] In 1624, a member of the Mosha'sha' also governed Dowraq for some time.[14]

Sayyed Mansur was the last vali of Hoveyzeh to challenge Safavid rule, refusing to carry out direct orders from Shah Abbas I in 1620, who as a result had him removed. In 1650, Sayyed Ali Khan ibn Mowla was appointed the new vali of Hoveyzeh. His inability to control the Arab tribes culminated in a revolt, which was eventually suppressed by Manuchehr Khan, the governor of Lorestan. The latter himself took control over Hoveyzeh, and had Sayyed Ali Khan and his sons sent to Isfahan. It is uncertain who governed Arabestan following this event; Manuchehr Khan controlled Hoveyzeh for two years, and then afterwards its fortress was controlled by an Iranian force under the command of Mohammad Mo'men Beg. The latter was succeeded in 1655 by Safiqoli Beg, better known as Taniya Beg.[15] During this period, Shushtar was governed by a Georgian gholam, Vakhushti Khan.[4]

In 1663, Sayyed Ali Khan ibn Mowla was restored as the vali of Hoveyzeh through the influence of the governor of Kuhgiluyeh, Zaman Khan.[16] Following the death of Sayyed Ali Khan in 1681 or 1687, a struggle for succession ensured amongst his brother Abdollah and sons. Order was only restored when Sayyed Farajollah was installed as the new vali in 1687.[15]

In 1736, Safavid rule over Iran was abolished and replaced by the Afsharid dynasty, established by the powerful Iranian commander Nader Shah (r. 1736–1747) of the Turkoman Afshar tribe.[17][18]

Administration

editUnder the Safavids, Arabestan was a velayat, i.e. an autonomously administered region. Arabestan was the highest ranking velayat, the other velayats being Lorestan, Georgia, Kurdistan, and Bakhtiyari territory.[19] Albeit the governing valis were chosen by the shah, they ruled in a hereditary manner.[20] The valis officially showed their fealty to the shah and minting coins in his name.[21] The valis had the right to request help from a Safavid vizier, who oversaw the affairs of Arabestan.[22]

Population

editSince the 16th century, Khuzestan was slowly becoming arabicized, due to new Arabic-speaking settlers arriving from Mesopotamia, such as the Banu Ka'b.[11] The population of Khuzestan was mixed, being mainly populated by Arab tribes, but also having Lor and Afshar inhabitants.[23] Hoveyzeh and its surroundings was most likely solely populated by Arabs, who may also have formed the majority around the Karun and beyond Ahvaz.[24] The Afshars of Khuzestan had inhabited the province since the end of the Seljuk period (1037–1194). They lived in a large area stretching from the east of Hoveyzeh to Dowraq, the latter which was their main center.[25] The Afshars restricted the influence of the Mosha'sha', whom they had unfriendly relations with.[26] The Mosha'sha' lived in Hoveyzeh.[11]

The Banu Ka'b, who had lived in the environs of Hoveyzeh and Kakha since the start of Safavid rule, expelled the Afshars from their lands following the death of Shah Tahmasp I (r. 1524–1576). During the rule of Shah Abbas I, the Banu Ka'b were driven out of the Afshar lands by the governor of Fars, Imam-Quli Khan, who gave the land back to the Afshars.[25]

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d Chehabi 2012, p. 209.

- ^ Jalalipour 2015, p. 6.

- ^ Matthee 2003, p. 267 (see also note 2).

- ^ a b c d Luft 1993, p. 673.

- ^ van Donzel 2022, p. 212.

- ^ Floor 2021, p. 218.

- ^ Matthee 2003, p. 267 (see note 2).

- ^ Savory 1986, p. 81.

- ^ Matthee 2015, pp. 449–450.

- ^ a b c d e Floor 2008, p. 143.

- ^ a b c d Matthee 2015, p. 450.

- ^ Floor 2008, pp. 142–143.

- ^ Luft 1993, p. 672.

- ^ Floor 2008, pp. 143–144.

- ^ a b Floor 2008, p. 144.

- ^ Floor 2008, pp. 144, 146.

- ^ Perry 1984, pp. 587–589.

- ^ Tucker 2006.

- ^ Matthee 2011, p. 143. For the meaning of velayat, see p. 141.

- ^ Matthee 2011, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Matthee 2011, p. 144.

- ^ Sanikidze 2021, p. 389.

- ^ Manz 2021, p. 183.

- ^ Soucek 1984, p. 204.

- ^ a b Bulookbashi & Negahban 2008.

- ^ Floor 2006, p. 279.

Sources

edit- Bulookbashi, Ali A.; Negahban, Farzin (2008). "Afshār". In Madelung, Wilferd; Daftary, Farhad (eds.). Encyclopaedia Islamica Online. Brill Online. ISSN 1875-9831.

- Chehabi, H. E. (2012). "Iran and Iraq: Intersocietal Linkages and Secular Nationalisms". In Amanat, Abbas; Vejdani, Farzin (eds.). Iran Facing Others: Identity Boundaries in a Historical Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 193–220. ISBN 978-1137013408.

- Floor, Willem (2006). "The Rise and Fall of the Banū Kaʿb. A Borderer State in Southern Khuzestan". Iran: Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies. 44 (1): 277–315. doi:10.1080/05786967.2006.11834690. S2CID 192691234.

- Floor, Willem (2008). Titles and Emoluments in Safavid Iran: A Third Manual of Safavid Administration, by Mirza Naqi Nasiri. Washington, D.C.: Mage Publishers. ISBN 978-1933823232.

- Floor, Willem (2021). "The Safavid court and government". In Matthee, Rudi (ed.). The Safavid World. Routledge. pp. 203–224.

- Jalalipour, Saeid (2015). "The Arab Conquest of Persia: The Khūzistān Province before and after the Muslims Triumph" (PDF). Sasanika.

- Luft, P. (1993). "Mus̲h̲aʿs̲h̲aʿ". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 672–675. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Manz, Beatrice Forbes (2021). Nomads in the Middle East. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781009213387.

- Matthee, Rudi (2003). "The Safavid Mint of Huwayza: The Numismatic Evidence". In Newman, Andrew J. (ed.). Society and Culture in the Early Modern Middle East: Studies on Iran in the Safavid Period. Brill. pp. 265–294.

- Matthee, Rudi (2011). Persia in Crisis: Safavid Decline and the Fall of Isfahan. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0857731814.

- Matthee, Rudi (2015). "Relations between the Center and the Periphery in Safavid Iran: The Western Borderlands v. the Eastern Frontier Zone". The Historian. 77 (3): 431–463. doi:10.1111/hisn.12068. S2CID 143393018.

- Perry, J. R. (1984). "Afsharids". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Volume I/6: Afghanistan–Ahriman. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 587–589. ISBN 978-0-71009-095-9.

- Sanikidze, George (2021). "The Evolution of the Safavid Policy towards Eastern Georgia". In Melville, Charles (ed.). Safavid Persia in the Age of Empires: The Idea of Iran. Vol. 10. I.B. Tauris. pp. 375–404.

- Savory, R.M (1986). "K̲h̲ūzistān". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume V: Khe–Mahi. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-90-04-07819-2.

- Soucek, Svat (1984). "Arabistan or Khuzistan". Iranian Studies. 17 (2–3): 195–213. doi:10.1080/00210868408701628. JSTOR 4310441. (registration required)

- Tucker, Ernest (2006). "Nāder Shah". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- van Donzel, E.J. (2022). Islamic Desk Reference: Compiled from The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill. ISBN 978-9004097384.

Further reading

edit- Akopyan, Alexander V. (2024). "Ugly Yet Popular: the Remarkably Long Life of the Safavid Coins of Hoveyza". Journal of Persianate Studies: 1–20. doi:10.1163/18747167-bja10038.