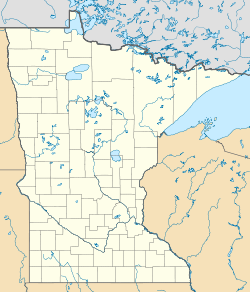

Saint Augusta or St. Augusta, formerly named Ventura, is a city in Stearns County, Minnesota, United States, directly south of the city of St. Cloud. The population was 3,497 at the 2020 census.[3]

St. Augusta | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Where Country Meets Community" | |

| Coordinates: 45°26′59″N 94°11′58″W / 45.44972°N 94.19944°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Minnesota |

| County | Stearns |

| Settled | 1854 |

| Organized | 1859 |

| Incorporated | May 2, 2000 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Mike Zenzen |

| • City Council | Jeff Schmitz Mary Coleman Brent Genereux Justin Backes |

| Area | |

| • Total | 29.84 sq mi (77.28 km2) |

| • Land | 29.68 sq mi (76.88 km2) |

| • Water | 0.15 sq mi (0.40 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,030 ft (310 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 3,497 |

| • Estimate (2021)[4] | 3,574 |

| • Density | 117.80/sq mi (45.48/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 56301 |

| Area code | 320 |

| FIPS code | 27-56752[5] |

| GNIS feature ID | 2396474[2] |

| Website | staugustamn.com |

St. Augusta is part of the Saint Cloud Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

editWriting in 1997, Jewish-American historian of America's religious architecture Marilyn J. Chiat described the early history of the region as follows, "Father Francis X. Pierz, a missionary to Indians in central Minnesota, published a series of articles in 1851 in German Catholic newspapers advocating Catholic settlement in central Minnesota. Large numbers of immigrants, mainly German, but also Slovenian and Polish, responded. Over 20 parishes where formed in what is now Stearns County, each centered on a church-oriented hamlet. As the farmers prospered, the small frame churches were replaced by more substantial buildings of brick or stone such as St. Mary, Help of Christians, a Gothic Revival stone structure built in 1873. Stearns County retains in its German character and is still home to one of the largest rural Catholic populations in Anglo-America."[6]

St. Augusta received its name because Fr. Pierz accidentally found a German language holy card dedicated to St. Augustine lying in the nearby field previously chosen for the building of their parish church. At Fr. Pierz's suggestion, the town was named for the Saint, although the city's name was somehow garbled in the process. The original holy card, however, is still preserved in the parish archives.[7]

Similarly to many other Stearns County German communities, the early settlers of St. Augusta included at least one Catholic family of German Jewish descent. The family patriarch was Baldassar Mayer (1816-1890), a native of the Grand Duchy of Baden. Raised in Orthodox Judaism, Mayer had converted to Roman Catholicism before his marriage to Dutch-American Gentile Elizabeth Hagedorn in Mercer County, Ohio. From the time of their first arrival in 1865, the Mayer family was very heavily involved in St. Mary, Help of Christians Parish, and Baldassar Mayer helped build the current church building during the early 1870s. He always retained, however, a very strong sense of pride in his Jewish ancestry and, shortly before his death on 4 July 1890, Mayer asked for his kippah, sat up in his deathbed, and sang two traditional blessings from the Hebrew Bible as an expression of his love for his family and his hopes for their future. Baldassar Mayer sang Eshet Ḥayil (Hebrew: אשת חיל, "Woman of Valor") Book of Proverbs Chapter 31 Verses 10–31, over his wife, and Birkut Kohanim (Hebrew: ברכת כהנים, "The Priestly Blessing"), Book of Numbers Chapter 6 Verses 23-27, over their many children and grandchildren.[8]

Just like the many other Stearns County German communities surrounding it, St. Augusta has produced plenty of voluntary recruits to the United States military during every one of America's wars from the American Civil War to the present, and even to the two World Wars that were fought against the St. Augustaners and Luxemburgers' ancestral homeland (German: die alte Heimat). On every Memorial Day, the local American Legion and Auxiliary holds annual ceremonies in all three cemeteries within the city, during which the names of all deceased local veterans are read aloud.[9]

Just as similarly to other communities in rural Stearns County during the Prohibition era, St. Augusta was a center for the secret distilling of a very high quality form of moonshine called Minnesota 13. According to local historian Sr. Janice Wedl, O.S.B., "People did get thirsty and made their own beer and hard liquor to drink and to sell. When the law caught up with them, the bottles containing the splendid brew were taken to the dump and smashed. For a while there was a moonshine still on the West side of the dam, near the Henry Kaeter farm. One night, during a dance at Schill's Hall, a huge explosion could be heard and a big fire could be seen near the dam. The Feds had discovered the moonshine still and blew it up."[10]

Also according to Sr. Janice, "The year the Prohibition Law was repealed (1933), Matt and Marie Ramacher bought the former Beumer Store and opened a grocery store and bar in downtown St. Augusta. This was the first bar in operation in St. Augusta Township after beer sales were legal again."[11]

Originally Saint Augusta Township, it incorporated as a city on May 2, 2000 in order to avoid annexation by the city of Saint Cloud.[citation needed] St. Augusta was named in the 1850s after a local church.[12] The city contains one property listed on the National Register of Historic Places: the 1873 St. Mary Help of Christians Church and its 1890 rectory.[13]

For a short time Saint Augusta was officially named Ventura in honor of then Governor Jesse Ventura, but voters decided on its current name months after incorporation, and the name was officially changed to Saint Augusta on November 7, 2000.[14]

St. Boniface Chapel & pilgrimage shrine

editThe Christian pilgrimage shrine (German: Wahlfahrtsort)[15] (German: Gnadenkapelle)[16][17] known as St. Boniface Chapel was built in 1877, similarly to the far more famous "Assumption Chapel" near Cold Spring, as a desperate petition for divine intervention from the Rocky Mountain locusts; a now extinct species of giant grasshopper, whose enormous migrating swarms blotted out the sunlight and, as described in the novel On the Banks of Plum Creek, Laura Ingalls Wilder, devastated farming communities throughout North America between 1856 and 1902.

Sr. Janice Wedl, O.S.B. has written about the four-year-long Locust Plague of 1874, "These huge insects destroyed everything in their path - crops, clothing hanging on wash lines, even fence posts. Nothing was safe, and many families lost everything they were growing for winter and all the crops they had planned to sell or feed to their livestock. Though people flailed at the insects, the swarms were so extensive, so pervasive that they had little hope of salvaging their lives without Divine help. The parishioners of St. Augusta and Luxemburg made a pledge to build a chapel and every year make a pilgrimage to it to pray that any future plagues be averted."[18]

Local farmer Henry Kaeter donated a plot of land[18] "half-way between their parish churches - on a small tree-crowned hill".[19] Ignatz Henkemeyer later recalled, "The grasshoppers were real bad. Everything dried up. After we finished at St. Boniface's, the rain started to fall, and all the hoppers flew up and disappeared."[20]

Annual pilgrimages to the shrine continued for many years afterwards on June 5, the Feast Day of St. Boniface, an English Benedictine missionary, Bishop, and martyr instrumental to the Christianisation of the Germanic peoples; and who is still revered as the "Apostle to the Germans", Patron Saint of the Germanosphere and the German diaspora.[21]

According to Fr. Robert J. Voigt, "The women decorated the chapel with flowers and choirs took their turn in singing and brought an organ along... Close to a hundred people, representing virtually every family, came. They came on foot, some as far as six miles, walked two by two and recited the rosary. A large spring wagon accompanied the people and carried the lunch."[21]

According to Fr. Robert J. Voigt, while praying the rosary, it is traditional in Stearns County German culture to mention which of the Mysteries of the Rosary is being focussed upon right after the Name of Jesus during each Hail Mary.[22] Local pilgrims praying the rosary upon St. Boniface's Day, would also add, following every Hail Mary, the additional petition, (German: "Heilige Bonifacius, bitte für uns!") ("St. Boniface, pray for us!")[18]

Ignatz Henkemeyer also recalled, "I remember looking down the hill. When the people came up the hill, singing all the way, it looked like a long train."[23]

According to Fr. Coleman J. Barry, there is traditionally a very intensive rivalry between parish choirs in Stearns County German culture. From the time of early settlement, every local parish choir used B.H.F. Hellebusch's Katholisches Gesang und Gebet Buch and the six Sing Messen found therein until the Regensburg-style of Gregorian Chant was introduced beginning in the 1880s. Parish choir-directors often doubled as local school-masters and were traditionally referred to as, (German: die Kirchen Väter), or "The Church Fathers". Catholic hymns in the German language (German: Kirchenlieder), which were always carefully chosen to fit the occasion, were also traditionally sung during Low Mass.[24]

Due to these intensive traditional parish rivalries, whenever the St. Boniface's Day pilgrimages would be followed by a Solemn High Mass at the chapel, both parish choirs would take turns singing. The Mass would always be followed with an open air dinner accompanied by dancing and the playing and singing of German folk music.[21]

According to local historian Fr. Colman J. Barry, this represented a continuation of the tradition of parish feast day picnics and old country festivals that, very similarly to the Pennsylvania Dutch Fersommling, remained a central pillar of Stearns County German culture. According to Fr. Barry, "These celebrations were always informal, and were not limited only to fairs but were held also on Christmas, New Years Day, Fastnacht or Shrove Tuesday, and at the end of the harvest season, Kirchweih Fest, the time when they had first dedicated their hard won churches to God. The pastors always attended, and favorite characters of the community were called upon to do stunts or recite poems of their childhood days in Europe. Some of the men would recall fire and brimstone mission sermons of former years and even repeat them. Always there was the beer, and when the tempo slowed down there was ever someone on hand to take up the old lustige Lieder." Popular songs at such gatherings included Muss i denn, Heidenröslein, Du, du liegst mir im Herzen, and O du lieber Augustin. It was particularly common at such gatherings for local Union Army veterans of the American Civil War to stand up and sing, with tears and intense emotion, a traditional soldiers' lament dating from the Napoleonic Wars, Ich hatt' einen Kameraden, in honor of their fallen friends.[25] (see German Americans in the American Civil War).

While no longer commonly performed locally, the latter song continues to be played at German and Austrian military funerals,[26] in mid-November at the annual ceremonies in both the Bundestag and at the Neue Wache for Volkstrauertag, the German Federal Republic's equivalent to Memorial Day, and every July 20 at the Memorial to the German Resistance at the Bendlerblock in Berlin.[27]

Sometimes, similarly to traditional Irish Pattern Days, rivalry between the two parishes would sometimes result in fist fights during the dinner, particularly when alcohol was involved.[28]

According to Fr. Robert J. Voigt, "In 1960, Fr. Louis Traufler, O.S.B., told this writer about the events at St. Boniface Chapel, which he himself had witnessed. At the picnic, there would be good natured bickering. The Luxemburgers would call the St. Augustaners (German: Speckfresser), because they were more prosperous and had meat to eat. The St. Augustaners called the Luxemburgers (German: Knochenknarrer), because they had to nibble on bones. At times they would challenge each other to cross a plank over the creek, and each side would try to throw the other in the water. This could end up in a fist fight between the young men... At the end of the day, a bell would ring and everyone would like up for the procession back to their parish churches - to be good boys again. The writer is reminded of what Joseph Knoll of Pierz told him years ago, (German: 'Sogar beim Begräbnis müß man Spaß haben, sonst geht niemand mit') ('Even at a funeral, there must be some pleasure; otherwise nobody will attend'). The parishioners went to the chapel to pray, but also wanted to have some fun."[29]

After 1897, the pilgrimages ceased and the chapel was abandoned and forgotten.[30] When asked why the traditional pilgrimage stopped, Mrs. Mary Kenning recalled, "The people who had made the vow were all dead or too old to go. Their children hadn't made the promise so they didn't have to continue the act. I guess it sort of came to a standstill."[31]

In 1937, the Henry Kaeter farm was purchased by Martin Libbesmeier, who was intrigued to discover the disused and crumbling chapel near his home.[30] The 1930s were a time, however, of rapidly escalating shame-based assimilation among German-Americans. This had very little to do with the pervasive anti-German sentiment and atrocity propaganda spread by both Wellington House and President Woodrow Wilson during the First World War, or even with the latter's regular denunciation of all allegedly Hyphenated Americans or with his support for the use of coercion in the schools by adherents of the English only movement. The real cause was the widespread shame, horror, self-hatred, and embarrassment felt by most German-Americans over Adolf Hitler's Enabling Act of 1933, the Nuremberg Laws, and, most of all, over the subversive domestic activities of the German-American Bund, the Silver Legion, and other Fascistic organizations receiving covert funding from the new police state in Nazi Germany.[32] For this reason, when Martin Libbesmeier approached the priest at St. Wendelin's Church seeking instructions on what to do with the ruins of St. Boniface Chapel, the priest urged him to set a match to them.[30]

Libbesmeier, however, wasn't at all happy with this answer and instead approached the priest at St. Augusta, who advised doing whatever else he preferred to do with the ruins. Libbesmeier accordingly moved the ruins into his yard, where they remained for 29 years. Over time, both the chapel crucifix and the statue of the Blessed Virgin fell and broke, and were buried in a local pasture.[33]

After taking the helm of St. Mary Help of Christians Church in 1958, Fr. Severin Schwieters was influential in convincing his parishioners that the chapel was a highly important local heritage monument and needed to be restored. At his urging, the parishioners moved the ruins to a wooded hill near the original site and reconstructed, as much as possible, using the original wood and other materials. St. Augustine's Church in east St. Cloud donated a new altar and all other items necessary for saying the Tridentine Mass. By St. Boniface's Day 1961, the chapel was ready for the annual pilgrimages to be revived, which still sometimes continues.[34] Trees were planted around the site by two volunteers in 1962.[35]

Meanwhile, the last documented sighting of live Rocky Mountain locusts took place in southern Canada in 1902.[36] In 2014, the species of insects which was once numerous enough to block out the sun and reduce farm families throughout North America to the brink of starvation was formally declared extinct by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.[37]

Geography

editAccording to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 29.81 square miles (77.21 km2); 29.66 square miles (76.82 km2) is land and 0.15 square miles (0.39 km2) is water.[38]

Minnesota State Highway 15 and County Route 7 are two of the main routes in Saint Augusta. Interstate 94/U.S. Highway 52 and County Route 75 skirt the northeastern border of St. Augusta. The city of Saint Cloud is to the immediate north and northeast of Saint Augusta.

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 798 | — | |

| 1890 | 791 | −0.9% | |

| 1900 | 819 | 3.5% | |

| 1910 | 766 | −6.5% | |

| 1920 | 821 | 7.2% | |

| 1930 | 949 | 15.6% | |

| 1940 | 968 | 2.0% | |

| 1950 | 904 | −6.6% | |

| 1960 | 1,056 | 16.8% | |

| 1970 | 1,584 | 50.0% | |

| 1980 | 2,169 | 36.9% | |

| 1990 | 2,657 | 22.5% | |

| 2000 | 3,065 | 15.4% | |

| 2010 | 3,317 | 8.2% | |

| 2020 | 3,497 | 5.4% | |

| 2021 (est.) | 3,574 | [4] | 2.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[39] 2020 Census[3] | |||

2010 census

editAs of the census of 2010, there were 3,317 people, 1,154 households, and 937 families living in the city. The population density was 111.8 inhabitants per square mile (43.2/km2). There were 1,184 housing units at an average density of 39.9 per square mile (15.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 97.4% White, 0.5% African American, 0.1% Native American, 0.7% Asian, 0.3% from other races, and 0.9% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.6% of the population.

There were 1,154 households, of which 39.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 71.9% were married couples living together, 4.6% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.7% had a male householder with no wife present, and 18.8% were non-families. 13.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 3.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.86 and the average family size was 3.13.

The median age in the city was 36.6 years. 27.1% of residents were under the age of 18; 7% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 28.2% were from 25 to 44; 29.4% were from 45 to 64; and 8.3% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 50.5% male and 49.5% female.

2000 census

editAs of the census of 2000, there were 3,065 people, 987 households, and 838 families living in the township. The population density was 81.4 inhabitants per square mile (31.4/km2). There were 1,000 housing units at an average density of 26.6 per square mile (10.3/km2). The racial makeup of the township was 98.79% White, 0.07% African American, 0.03% Native American, 0.52% Asian, 0.03% from other races, and 0.55% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.39% of the population.

There were 987 households, out of which 47.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 76.5% were married couples living together, 5.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 15.0% were non-families. 11.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 3.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.11 and the average family size was 3.38.

In the township the population was spread out, with 31.6% under the age of 18, 8.5% from 18 to 24, 30.8% from 25 to 44, 22.9% from 45 to 64, and 6.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 102.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 103.9 males.

The median income for a household in the township was $57,292, and the median income for a family was $60,000. Males had a median income of $36,148 versus $24,554 for females. The per capita income for the township was $21,712. About 2.1% of families and 2.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including none of those under age 18 and 22.6% of those age 65 or over.

Education

editMost of St. Augusta is in the St. Cloud Area School District. A portion is in the Kimball Public School District.[40]

Three elementary schools have boundaries including portions of the St. Cloud section: Clearview, Discovery, and Oak Hill.[41] All of the St. Cloud school district portion of St. Augusta is zoned to South Middle School and Technical Senior High School.[42][43]

References

edit- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: St. Augusta, Minnesota

- ^ a b c "Explore Census Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 15, 2023.

- ^ a b "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2021". United States Census Bureau. March 15, 2023. Retrieved March 15, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Marilyn J. Chiat (1997), America's Religious Architecture: Sacred Places for Every Community, Preservation Press. Page 146.

- ^ Janice Wedl, O.S.B. (2005), A Dwelling Place for God: The History of St. Mary, Help of Christians Parish, St. Augusta, Minnesota, North Star Press, St. Cloud, Minnesota. Pages 4-5.

- ^ Janice Wedl, O.S.B. (2005), A Dwelling Place for God: The History of St. Mary, Help of Christians Parish, St. Augusta, Minnesota, North Star Press, St. Cloud, Minnesota. Pages 32-33.

- ^ Janice Wedl, O.S.B. (2005), A Dwelling Place for God: The History of St. Mary, Help of Christians Parish, St. Augusta, Minnesota, North Star Press, St. Cloud, Minnesota. Pages 98-100.

- ^ Janice Wedl, O.S.B. (2005), A Dwelling Place for God: The History of St. Mary, Help of Christians Parish, St. Augusta, Minnesota, North Star Press, St. Cloud, Minnesota. Pages 107-109.

- ^ Janice Wedl, O.S.B. (2005), A Dwelling Place for God: The History of St. Mary, Help of Christians Parish, St. Augusta, Minnesota, North Star Press, St. Cloud, Minnesota. Page 109.

- ^ Upham, Warren (1920). Minnesota Geographic Names: Their Origin and Historic Significance. Minnesota Historical Society. p. 526.

- ^ "Minnesota National Register Properties Database". Minnesota Historical Society. 2009. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ^ Population Estimates Geographic Change Notes: Minnesota, May 19, 2006. Accessed May 28, 2008. [dead link]

- ^ Fr. Robert J. Voigt (1991), The Story of Mary and the Grasshoppers, Cold Spring, Minnesota. Pages 17.

- ^ Fr. Robert J. Voigt (1991), The Story of Mary and the Grasshoppers, Cold Spring, Minnesota. Pages 28.

- ^ Gross, Stephen John (April 2006). "The Grasshopper Shrine at Cold Spring, Minnesota: Religion and Market Capitalism among German-American Catholics" (PDF). The Catholic Historical Review. 92 (2): 215–243. doi:10.1353/cat.2006.0133. S2CID 159890053.

- ^ a b c Janice Wedl, O.S.B. (2005), A Dwelling Place for God: The History of St. Mary, Help of Christians Parish, St. Augusta, Minnesota, North Star Press, St. Cloud, Minnesota. Pages 110.

- ^ Fr. Robert J. Voigt (1991), The Story of Mary and the Grasshoppers, Cold Spring, Minnesota. Pages 25.

- ^ Janice Wedl, O.S.B. (2005), A Dwelling Place for God: The History of St. Mary, Help of Christians Parish, St. Augusta, Minnesota, North Star Press, St. Cloud, Minnesota. Pages 111.

- ^ a b c Fr. Robert J. Voigt (1991), The Story of Mary and the Grasshoppers, Cold Spring, Minnesota. Page 25.

- ^ Fr. Robert J. Voigt (1991), The Story of Mary and the Grasshoppers, Cold Spring, Minnesota. Page 41.

- ^ Janice Wedl, O.S.B. (2005), A Dwelling Place for God: The History of St. Mary, Help of Christians Parish, St. Augusta, Minnesota, North Star Press, St. Cloud, Minnesota. Pages 110-111.

- ^ Coleman J. Barry (1956), Worship and Work: Saint John's Abbey and University 1856-1956, Order of St. Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. Pages 90-92.

- ^ Coleman J. Barry (1956), Worship and Work: Saint John's Abbey and University 1856-1956, Order of St. Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. Pages 89-90.

- ^ R. Oeding, Das deutsche Totensignal, 2013

- ^ "Ich hatte einem Kameraden" (The Good Comrade)

- ^ Fr. Robert J. Voigt (1991), The Story of Mary and the Grasshoppers, Cold Spring, Minnesota. Pages 25-27.

- ^ Fr. Robert J. Voigt (1991), The Story of Mary and the Grasshoppers, Cold Spring, Minnesota. Page 26.

- ^ a b c Janice Wedl, O.S.B. (2005), A Dwelling Place for God: The History of St. Mary, Help of Christians Parish, St. Augusta, Minnesota, North Star Press, St. Cloud, Minnesota. Pages 112.

- ^ Fr. Robert J. Voigt (1991), The Story of Mary and the Grasshoppers, Cold Spring, Minnesota. Pages 26-27.

- ^ Richard O'Connor (1968), The German-Americans: An Informal History, Little, Brown & Company. Pages 429-464.

- ^ Janice Wedl, O.S.B. (2005), A Dwelling Place for God: The History of St. Mary, Help of Christians Parish, St. Augusta, Minnesota, North Star Press, St. Cloud, Minnesota. Pages 112-113.

- ^ Janice Wedl, O.S.B. (2005), A Dwelling Place for God: The History of St. Mary, Help of Christians Parish, St. Augusta, Minnesota, North Star Press, St. Cloud, Minnesota. Page 113.

- ^ Janice Wedl, O.S.B. (2005), A Dwelling Place for God: The History of St. Mary, Help of Christians Parish, St. Augusta, Minnesota, North Star Press, St. Cloud, Minnesota. Pages 112-192.

- ^ Canada's History, October–November 2015, pages 43-44

- ^ "Melanoplus spretus, Rocky Mountain grasshopper". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 20, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2012.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved September 11, 2013.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Stearns County, MN" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

- ^ "Elementary Attendance Areas" (PDF). St. Cloud Area School District. Retrieved November 8, 2022. - Clearview detail map, Discovery detail map, Oak Hill detail map all linked from here - Compare to census maps.

- ^ "SOUTH Versatrans Base Map" (PDF). St. Cloud Area School District. Retrieved November 8, 2022. - linked from here - Compare to census maps.

- ^ "TECH Versatrans Base Map" (PDF). St. Cloud Area School District. Retrieved November 8, 2022. - linked from here - Compare to census maps.