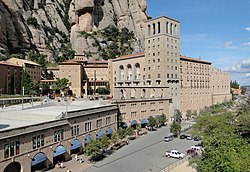

Santa Maria de Montserrat (Catalan pronunciation: [ˈsantə məˈɾi.ə ðə munsəˈrat]) is an abbey of the Order of Saint Benedict located on the mountain of Montserrat in Monistrol de Montserrat, Catalonia, Spain. It is notable for enshrining the image of the Virgin of Montserrat. The monastery was founded in 1025 and rebuilt between the 19th and 20th centuries. With a community of around 70 monks, the abbey is still in use to this day.[1]

Monestir de Montserrat | |

Abbey of Montserrat | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Order | Benedictine |

| Established | 1025 |

| Dedicated to | Virgin of Montserrat |

| Diocese | Sant Feliu de Llobregat |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | Bien de Interés Cultural |

| Site | |

| Location | Montserrat, Monistrol de Montserrat, Catalonia, Spain |

| Coordinates | 41°35′35.54″N 1°50′13.70″E / 41.5932056°N 1.8371389°E |

| Website | www |

| |

Location

editThe monastery is 48 kilometres (30 mi) northwest of Barcelona, and can be reached by road, train or cable car. The abbey's train station, operated by FGC, is the terminus of a rack railway connecting with Monistrol, and two funiculars, one connecting with Santa Cova (a shrine and chapel lower down the mountain) and the other connecting with the upper slopes of the mountain. At 1,236 metres (4,055 ft) above the valley floor, Montserrat is the highest point of the Catalan lowlands, and stands central to the most populated part of Catalonia. Montserrat's highest point, Sant Jeroni, can be reached by footpaths leading from the monastery. From Sant Jeroni, almost all of Catalonia can be seen, and on a clear day the island of Mallorca is visible.

Description

editMontserrat, whose name means 'serrated mountain', plays an important role in the cultural and spiritual life of Catalonia. It is Catalonia's most important religious retreat and groups of young people from Barcelona and all over Catalonia often make overnight hikes to watch the sunrise from the heights of Montserrat. The Virgin of Montserrat is Catalonia's patron saint, and is located in the sanctuary of the Mare de Déu de Montserrat, next to the Benedictine monastery nestling in the towers and crags of the mountain.

There are generally about 80 monks in residence. The Escolania, Montserrat's Boys’ Choir, is one of the oldest in Europe, and performs during religious ceremonies and communal prayers in the basilica.

The basilica houses a museum with works of art by many prominent painters. The Publicacions de l'Abadia de Montserrat, a publishing house, is one of the oldest presses in the world still running,[2][3] with its first book published in 1499.

Basilica of Montserrat

editInitial construction of the basilica of Montserrat began in the 16th century, and its complete reconstruction began in the year 1811, after being destroyed in the Peninsular War.

In 1881 the Pope Leo XIII granted it the status of minor basilica. The facade was realized in 1901, work of Francisco de Paula del Villar y Carmona in Plateresque Revival style, with sculptural reliefs of Venanci and Agapit Vallmitjana i Barbany.

After the Spanish Civil War a new façade of the church was built (between 1942 and 1968),[4] with the work of Francesc Folguera i Grassi and decorated with sculptural reliefs of Joan Rebull (St. Benedict, Proclamation of the dogma of the Assumption of Mary by Pius XII and St. George, with a representation of the monks who died during the Spanish Civil War). Additionally, it bears the inscription Urbs Jerusalem Beata Dicta Pacis Visio ("Blessed city of Jerusalem, called the vision of peace"). At the foot of the frieze with the relief of St. George is sculpted the phrase "Catalonia will be Christian or it will not be", attributed to the bishop Josep Torras i Bages, which has been assumed as a political motto of Catholic root.

This facade precedes the church proper, which is accessed through an atrium. Here are the 16th century sepulchres[4] of Juan de Aragón y de Jonqueras, 2nd count of Ribagorza and Bernat II of Vilamarí. There are also several sculptures: St. John the Baptist and St. Joseph (1952),[4] of Josep Clarà, and St. Benedict (1962),[4] by Domènec Fita i Molat. There are also the paintings Visit of the Catholic Monarchs to Montserrat and Visit of Don John of Austria to Montserrat (1921)[4] by Francesc Fornells-Pla. The square that precedes the church (called del Abat Argeric, built in 18th century)[4] is decorated with sgraffitos (1956)[4] of Josep Obiols i Palau and the friar Benet Martínez, which represent the history of Montserrat and the main basilicas of the world. The square also houses various sculptures: St. Anthony Mary Claret (1954),[4] by Rafael Solanic; John I of Aragon (1956)[4] and St. Gregory the Great (1957),[4] by Frederic Marès; and St. Pius X, by F. Bassas. On one side is the baptistery (1958),[4] with a portal sculpted by Charles Collet,[4] and inside a mosaic made by Santiago Padrós (1918-1971)[4] and a drawing of the Baptism of Jesus by Josep Vila-Arrufat. Next to the baptistery there is a sculpture of St. Ignatius of Loyola, a work by Rafael Solanic.[5]

The church is of a single nave, 68.32 meters long and 21.50 wide, with a height of 33.33 meters. It is supported by central columns, carved in wood by Josep Llimona i Bruguera, representing the prophets Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and Daniel. At the head is the main altar, decorated with enamels (1928) of Montserrat Mainar, depicting various biblical scenes, such as The Last Supper, The Wedding at Cana and The Multiplication of Loaves and Fishes. The 15th century cross on the altar is the work of Lorenzo Ghiberti. On the altar there is a shrine of octagonal form. In the chancel there are various paintings by Alexandre de Riquer, Joan Llimona, Joaquim Vancells, Dionís Baixeras and Lluís Graner.[6]

Just above the main altar is located the room of the Virgin that is accessed after crossing a portal of alabaster (Porta Angèlica) in which are represented various biblical scenes, work of Enric Monjo (1954).[4] The mosaics on the walls represent the Saints Mothers (left) and the Saints Vírgins (right), the work of the friar Benet Martínez. Next comes the Throne Room (1944-1954),[4] the work of Francesc Folguera, decorated with paintings by Josep Obiols (Judith Who Cuts Off Holofernes's Head, Esther's Wedding with the Persian King Asuero) and Carlo Maratta (Birth of Jesus). The Fountain of the Virgin is also found here, with reliefs of Charles Collet representing the miracles of Jesus. The Throne of the Virgin is embossed silver, the work of goldsmith Ramon Sunyer, with two reliefs made by Alfons Serrahima and designed by Joaquim Ros i Bofarull that represent the Nativity and the Visitation, and an image of St. Michael by Josep Granyer. Here is a 12th-century statue of the Virgin on which are placed some angels that hold the crown, the scepter and the lily of the Virgin, the work of Martí Llauradó,[4] covered by a baldachin. The Sala del Cambril is a circular chapel with three apses, built between 1876 and 1884 by Villar i Carmona with the collaboration of his assistant, a young Antoni Gaudí. The vault is decorated by Joan Llimona (The Virgin Welcomes the Romeros) and the figures of angels and the sculpture of St. George are of Agapit Vallmitjana. The windows are of Antoni Rigalt i Blanch.[7] The exit of the room is carried out by the Camí de l'Ave Maria, where it is customary to make offerings in the form of candles. Here stands out a statue of the Angel of the Annunciation by Apel·les Fenosa, as well as a maiolica ceramic depicting the Virgin, the work of Joan Guivernau.[8]

Around the central nave there are several chapels. On the right are the Saint Peter chapel with the image of St. Peter by Josep Viladomat (1945); the St. Ignatius of Loyola chapel by Venanci Vallmitjana with a painting of St. Ignatius by Ramir Lorenzale (1893); the St. Martin of Tours chapel, work of Josep Llimona, with the images of St. Martin, St. Placidus and St. Maurus (1898); the St. Joseph Calasanz chapel with an altarpiece of Francesc Berenguer (1891); and that of St. Benedict with a painting of the founding saint of the Benedictine Order (1980) by Montserrat Gudiol. On the left are the chapel of Santa Escolàstica, with sculptures (1886) by Enric Clarasó and Agapito Vallmitjana; the chapel of del Santíssim (1977), work of Josep Maria Subirachs, with a singular image of Christ realized in negative, where only the face, the hands and the feet are seen, with a light that illuminates the face to him; the Holy Family chapel, where the painting The Flight to Egypt, by Josep Cusachs (1904); the Santo Cristo chapel, with an image of Josep Llimona (1896) facing the painting of "The Pietà of Montserrat" by the doctor and painter Josep Lluís Arimany (1995); and the chapel of the Immaculada Concepció (1910) a Modernisme work by Josep Maria Pericas, with a stained glass window by Darius Vilàs.[9]

The basilica was restored between 1991 and 1995 by Arcadi Pla i Masmiquel. In 2015 Sean Scully restyled Santa Cecilia Chapel which is next to the abbey.[10]

Pipe organ

editThe pipe organ of the church of Montserrat dates from 1896 and was moved to the presbytery in 1957. This pipe organ is very deteriorated. A new pipe organ was inaugurated in 2010 and follows the design of the Catalan pipe organs that are located next to the church. It is an important work of Catalan musical craftsmanship that places Montserrat at an international musical level. This pipe organ is designed by Albert Blancafort, built by Blancafort, orgueners de Montserrat, and financed by popular subscription and the social work of the Caixa de Penedes. The pipe organ is located on the side of the nave, as is traditional in Catalonia, offering a very good sound throughout the church.

Cloister

editThe cloister of the monastery is the work of the architect Josep Puig i Cadafalch (1929). It is two floors, supported by stone columns. The lower floor communicates with the garden and has a fountain in its central area. On the walls of the cloister, the visitor can see old pieces, some of 10th century. The extensive garden includes the Chapel of Sant Iscle and Santa Victòria, Romanesque, access to the buildings of the novitiate and the choir and several sculptures, such as the marble of the "Good Shepherd" of Manolo Hugué or some of the sculptures that Josep de San Benet made in the 18th century for the bell tower of the monastery that were never installed.

Refectory

editThe refectory is from the 17th century and it was rebuilt in 1925 by Puig i Cadafalch. The central part has a mosaic that represents Christ, while in the opposite area the visitor can see a triptych with scenes from the life of St. Benedict.

Museum

editThe monastery has an important museum divided into three different sections:

- Modern painting, with works by artists from Catalonia such as Santiago Rusiñol, Ramon Casas, Isidre Nonell, Joaquim Mir, Salvador Dalí, Joan Miró and Antoni Tàpies, and non-Catalans like Pablo Picasso or the painter Darío de Regoyos, an Asturian, who was the only painter linked to the European impressionist and neo-impressionist movements; as well as a representation of French impressionism, with authors such as Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley and Edgar Degas.

- Archeology of the biblical East, showing objects from Egypt, Cyprus, Mesopotamia and the Holy Land.

- Ancient painting, showing works by artists such as El Greco, Caravaggio (including an important St. Jerome), Luca Giordano, Giambattista Tiepolo and Pedro Berruguete.

Other collections include Montserrat iconography and religious goldsmithing.[11]

History

editThe legend places the finding of the statue of the Virgin of Montserrat around 880.[12] Then began the cult of the Moreneta virgin, which materialized in four earlier hermitages in the 9th century: Santa Maria, Sant Iscle, Sant Pere and Sant Martí. However, the origin of the monastery is uncertain. It is known that around 1011 a monk from the monastery of Santa Maria de Ripoll came to the mountain to take charge of the monastery of Santa Cecília de Montserrat, thus leaving the monastery under the orders of Abbot Oliba of Ripoll. Santa Cecília did not accept this new situation, so Oliba decided to found the monastery of Santa Maria in the place where there was an old hermitage of the same name (1025). As of 1082, Santa Maria gained an abbot of her own and ceased to depend on the abbot of Ripoll. This hermitage had become the most important of all those that existed in the mountain thanks to the statue of the Virgin that was venerated in it since 880.

In 1811 and in 1812, during Napoleon's invasion of Spain, the abbey was twice burned down and sacked by Napoleon's troops, and many of its treasures were lost. In 1835, the abbey was closed until restoration in 1844.

In 1880, Montserrat celebrated 1000 years of existence. On 11 September 1881, to coincide with the Catalan national day Pope Leo XIII proclaimed the Virgin of Montserrat patron of Catalonia.

Spanish Civil War

editThe Spanish Civil War saw the violent suppression of the Abbey of Montserrat. Of the 278 priests and 583 religious men and women killed in Catalonia by Republican forces,[13] 22 were monks of the Abbey of Montserrat.[14] The Spanish Republican authorities and the authorities of the Generalitat de Catalunya, such as Lluís Companys, Ventura Gassol and Joan Casanovas, tried to stop anticlerical violence and helped many priests and religious people to hide and leave the country.[15]

Francoist era

editThough Franco never accepted Hitler's invitation to join WWII on the Axis side, Nazi leaders were regular visitors to Spain. During a visit to Spain in 1940, Heinrich Himmler, the head of the Schutzstaffel, took the opportunity to visit the monastery of Santa Maria de Montserrat.[16]

During the rule of Francisco Franco, Santa Maria de Montserrat was seen as a sanctuary for scholars, artists, politicians and students. Franco's men were often waiting for wanted people a few miles down the road.[17]

From the 1940s onward, Santa Maria de Montserrat Abbey was often seen as a symbol of Catalan nationalism.[18] On 27 April 1947, a Mass was held to celebrate the Enthronement of the Virgin of Montserrat, and attended by over 100,000 people.[18] At the Mass, prayers were publicly said in the Catalan language, defying the government's language policies.[18]

Amid other activities, the Abbey of Montserrat played a remarkable part in continuing to publish in Catalan. They created and promoted, among others, some children's publications (L'Infantil, Tretzevents) and some cultural and religious journals (Serra d'Or, Qüestions de vida cristiana). In 1958, tile Abbey founded the Estela Press to promote religious books in Catalan (Masot i Muntaner, 1986). In 1971 the PAM Press (Publications of the Montserrat's Abbey) became official (Faulí, 1999, pp. 35–9). The abbey was also active in providing shelter to intellectuals and clandestine political activists from a wide political spectrum.[19]

In December 1970, 300 Spanish artists and academics held a sit-in at the abbey to protest against the death sentences meted out to 16 Basque ETA terrorists in Burgos. In response, the police sealed off the monastery.[20][21] The protesters were eventually removed from the monastery grounds, but their actions helped convince the Francoist government to commute the death sentences.[22]

List of priors and abbots

editPriors (1082–1408)

edit- Ramon (1082–1094)

- Gervasi (1088, 1101–1113/19)

- Bernat (1089, 1095/96–1098)

- Ramon (1105)

- Berenguer Bernat (1114/19–1124)

- Guillem (1131)

- Ponç (1136)

- Andreu (1139–1144)

- Bertran (1141)

- Guillem (1144–1147)

- Ponç (1151–1154)

- Pere de Sesguinyoles (1156–1166)

- Arnau (1159)

- Bertran de Maçans (1171–1202)

- Guillem Adalbert (1204–1207)

- Arnau d'Olivella (1208–1221)

- Ramon de Montlleó (1215)

- Bernat de Peramola (1217)

- Ramon (1219)

- Berenguer de Bac (1223–1236)

- Ramon (1227–1228)

- Guillem de Bellver (1236–1246)

- Bertran de Bac (1247–1272/73), also abbot of Ripoll from 1258

- Ramon de Calonge (1269–1271)

- Pere de Bac (1273–1280)

- Bernat Salvador (1284–1299)

- Bernat Esquerre (1300–1321/22)

- Gallard de Balaguer (1322–1328)

- John of Aragon (1328–1334), also archbishop of Tarragona and patriarch of Alexandria

- Ramon de Vilaragut (1334–1348)

- Jaume de Vivers (1348–1375)

- Rigalt de Vergne o de Vern (1375–1384)

- Vicenç de Ribes (1384–1408)

Abbots (1409–present)

edit- Marc de Vilalba (1409–1440)

- Antoni d'Avinyó i de Moles (1440–1450)

- Antoni Pere Ferrer (1450–1471/72)

- Giuliano della Rovere (1472–1483)

- Joan de Peralta (1483–1493)

- García Jiménez de Cisneros (1499–1510)

- Pedro Muñoz (1510–1512)

- Pedro de Burgos (1512–1536)

- Miguel Pedroche (1536–1541)

- Miquel Forner (1541–1544), first time

- Alonso de Toro (1544–1545)

- Miquel Forner (1546–1553), second time

- Diego de Lerma (1553–1556)

- Benet de Tocco (1556–1559), first time

- Bartomeu Garriga (1559–1562), first time

- Benet de Tocco (1562–1564), second time, later bishop of Vic, Girona and Lleida

- Felipe de Santiago (1564–1568), first time

- Bartomeu Garriga (1568–1570), second time

- Andrés de San Román (1570–1576)

- Felipe de Santiago (1576–1578), second time

- Andrés de Intriago (1578–1584)

- Jaume Forner (1585), president

- Jaume Capmany (1585–1586), president

- Jaume Capmany (1586–1590)

- Plácido Salinas (1590–1592)

- Jaume Forner (1592–1595)

- Antonio de Córdoba (1595)

- Lorenzo Nieto (1596–1598), first time

- Joaquim Bonanat (1598–1601)

- Lorenzo Nieto (1601–1604), second time

- Antoni Jutge (1604–1607), first time

- Juan de Valenzuela (1607–1610), first time

- Antoni Jutge (1610–1613), second time

- Andrés Correa (1613–1614)

- Juan de Valenzuela (1615–1617), second time

- Josep Costa (1617–1621)

- Alonso Gómez (1621–1625)

- Beda Pi (1625–1629)

- Pedro de Burgos (1629–1633)

- Josep Porrassa (1633–1636)

- Francesc Veils (1636–1637)

- Juan Manuel de Espinosa (1637–1641), later bishop of Urgell and archbishop of Tarragona

- Joan Marc (1641), president

- Francesc Batlle (1641–1645), first time

- Jaume Martí i Marvà (1645–1649)

- Francesc Batlle (1649–1653), second time

- Francisco Crespo (1653)

- Milán de Miranda (1653–1657)

- Jaume Saragossa (1657–1661)

- Esteban Velázquez (1661–1665), first time

- Plàcid Riquer (1665–1668)

- Lluís Montserrat (1668–1669)

- Esteban Velázquez (1669–1673), second time

- Josep Ferran (1673–1677)

- Plácido de la Reguera (1677–1681)

- Francesc Albià (1681)

- Benet de Sala i de Caramany (1682–1684), later bishop of Barcelona and cardinal

- Miquel Pujol (1684–1685)

- Juan Jiménez (1685–1689)

- Francesc de Cordelles (1689–1693)

- Juan Jiménez (1693–1697)

- Josep Ferrer (1697–1701)

- Gaspar Paredes (1701–1705)

- Fèlix Ramoneda (1705–1709)

- Pedro Cañada (1709–1713)

- Pedro Arnedo (1713)

- Manuel Marrón (1713–1717)

- José Benito (1717–1721)

- Esteban Rotalde (1721–1725)

- Benito Tizón (1725-?)

- Agustí Novell (?-?)

- Benito Tizón (1733–1734)

- Plàcid Cortada (1737–1741)

- José Romero (1741–1745)

- Carles Corts (1745–1749)

- Mauro Salcedo (1749–1753), first time

- Benet Argeric (1753–1757), first time

- Mauro Salcedo (1757–1761), second time

- Benet Argeric (1761–1764), second time

- Antoni Burgués (1764), first time

- Josep Morata (1756–1766)

- Plàcid Regidor (1766–1769)

- Antoni Burgués (1769–1773), second time

- Isidoro González (1773–1777)

- Pere Viver (1777–1781), first time

- José Arredondo (1789–1793)

- Pere Viver (1793–1796), second time

- Maur Llampuig (1796)

- Bernardo Ruiz (1797–1801)

- Bernat Sastre (1801–1805)

- Domingo Filgueira (1805–1809)

- Francesc Burgués (1810–1814)

- Simó de Guardiola i Hortoneda (1814–1818)

- Bernardo Bretón (1818–1824)

- Josep Blanch i Graells (1824–1828), first time

- Benito Varoja (1828–1832)

- Josep Blanch i Graells (1832–1851), second time

- Ramir Torrents i Torrents (1852–1853), president

- Ignasi Corrons (1853–1855), president

- Miquel Muntadas i Romaní (1855–1885), president until 1858

- Josep Deàs i Villar (1885–1913)

- Antoni Maria Marcet i Poal (1913–1946)

- Aureli Maria Escarré (1946–1966)

- Gabriel Maria Brasó i Tulla (1961–1966), coadjutor

- Cassià Maria Just i Riba (1966–1989)

- Sebastià Bardolet i Pujol (1989–2000)

- Josep Maria Soler i Canals (2000–2021)

- Manel Gasch i Hurios (2021– )

In fiction

editThe opening chapter of Dan Brown's 2017 novel Origin is set in Santa Maria de Montserrat. In the book, a crucial, secret meeting is held between an outspoken atheist and major Catholic, Jewish and Muslim clergymen.

See also

edit- Llibre Vermell de Montserrat

- Saint Jerome in Meditation (Caravaggio)

- Joan Cererols

- A year’s journey through France and Spain, Vol 1, 1777 Philip Thicknesse Letter xx onwards

References

edit- ^ "History", Abadia de Montserrat

- ^ La impremta a Montserrat. Manuel Llanas. Universitat de Vic, 2002.

- ^ Cinc-cents anys de Publicacions de l'Abadia de Montserrat. Faulí, Josep, Francesc Xavier Altés i Aguiló & Josep Massot i Muntaner. Publicacions de l'Abadia de Montserrat, 2005.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Molas i Rifà, Jordi (1998). Guía oficial de Montserrat. L'Abadia de Montserrat. ISBN 978-84-7826-956-3.

- ^ Molas i Rifà 1998, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Molas i Rifà 1998, p. 32.

- ^ Molas i Rifà 1998, pp. 34–39.

- ^ Molas i Rifà 1998, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Molas i Rifà 1998, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Sharp, Rob (June 30, 2015). "Sean Scully Fills a Spanish Monastery With Bursts of Color". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ Molas i Rifà 1998, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Molas i Rifà 1998, p. 12.

- ^ Archdiocese of Barcelona website

- ^ "Don Quixote website, the Monastery of Montserrat". donQuijote. Archived from the original on 2 August 2023.

- ^ Preston, Paul. The Spanish Holocaust, London, Harper Press, 2012.

- ^ "Himmler, Montserrat y el Santo Grial: la factura de una visita desagradable". El Confidencial (in Spanish). 2017-05-24. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ MacNeil, Karen (January 2001). MacNeil, Karen. The Wine Bible, p. 466. ISBN 9781563054341.

- ^ a b c Conversi, Daniele. The Basques, the Catalans, and Spain: Alternative Routes to Nationalist Mobilisation University of Nevada Press, 2000 ISBN 0874173620, (p 126-127).

- ^ Guibernau, Montserrat. NATIONALISM AND INTELLECTUALS IN NATIONS WITHOUT STATES: THE CATALAN CASE, Political Studies. Dec2000, Vol. 48 Issue 5, p989. 17p.

- ^ "Basque Trial Protesters Sealed Off", Associated Press, in Press-Courier, Dec 14, 1970, (pg. 9).

- ^ Mcneill, Donald, Urban change and the European left: tales from the new Barcelona, Routledge, 1999. ISBN 0415170621, (p. 142).

- ^ "After the Burgos Trials", Juan Marchial, Boston Globe, December 30, 1970 (p.8).

External links

editMedia related to Santa Maria de Montserrat at Wikimedia Commons