The Irish Free State (6 December 1922 – 29 December 1937), also known by its Irish name Saorstát Éireann (English: /ˌsɛərstɑːt ˈɛərən/ SAIR-staht AIR-ən,[4] Irish: [ˈsˠiːɾˠsˠt̪ˠaːt̪ˠ ˈeːɾʲən̪ˠ]), was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between the forces of the Irish Republic – the Irish Republican Army (IRA) – and British Crown forces.[5]

Irish Free State Saorstát Éireann (Irish) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1922–1937 | |||||||||||

| Anthem: "Amhrán na bhFiann"[1] "The Soldiers' Song" | |||||||||||

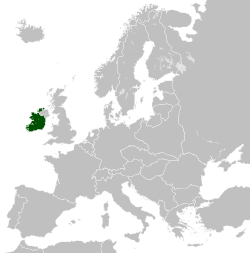

The Irish Free State (green) in 1929 | |||||||||||

| Status | British Dominion (1922–1931)[a]

Sovereign state (1931–1937)[b] | ||||||||||

| Capital and largest city | Dublin 53°21′N 6°16′W / 53.350°N 6.267°W | ||||||||||

| Official languages | |||||||||||

| Religion (1926[2]) |

| ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Irish | ||||||||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy | ||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||

• 1922–1936 | George V | ||||||||||

• 1936 | Edward VIII | ||||||||||

• 1936–1937 | George VI | ||||||||||

| Governor-General | |||||||||||

• 1922–1927 | Timothy Michael Healy | ||||||||||

• 1928–1932 | James McNeill | ||||||||||

• 1932–1936 | Domhnall Ua Buachalla | ||||||||||

| President of the Executive Council | |||||||||||

• 1922–1932 | W. T. Cosgrave | ||||||||||

• 1932–1937 | Éamon de Valera | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Oireachtas | ||||||||||

| Seanad | |||||||||||

| Dáil | |||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

| 6 December 1922 | |||||||||||

| 29 December 1937 | |||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| Until 8 December 1922[citation needed] | 84,000 km2 (32,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| After 8 December 1922[citation needed] | 70,000 km2 (27,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1936 | 2,968,420[3] | ||||||||||

| Currency |

| ||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC | ||||||||||

• Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (IST/WEST) | ||||||||||

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy | ||||||||||

| Drives on | left | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Free State was established as a dominion of the British Empire. It comprised 26 of the 32 counties of Ireland. Northern Ireland, which was made up of the remaining six counties, exercised its right under the Treaty to opt out of the new state. The Free State government consisted of the Governor-General – the representative of the king – and the Executive Council (cabinet), which replaced both the revolutionary Dáil Government and the Provisional Government set up under the Treaty. W. T. Cosgrave, who had led both of these administrations since August 1922, became the first President of the Executive Council (prime minister). The Oireachtas or legislature consisted of Dáil Éireann (the lower house) and Seanad Éireann (the upper house), also known as the Senate. Members of the Dáil were required to take an Oath of Allegiance to the Constitution of the Free State and to declare fidelity to the king. The oath was a key issue for opponents of the Treaty, who refused to take it and therefore did not take their seats. Pro-Treaty members, who formed Cumann na nGaedheal in 1923, held an effective majority in the Dáil from 1922 to 1927 and thereafter ruled as a minority government until 1932.

In 1931, with the passage of the Statute of Westminster, the Parliament of the United Kingdom relinquished nearly all of its remaining authority to legislate for the Free State and the other dominions. This had the effect of granting the Free State internationally recognised independence.

In the first months of the Free State, the Irish Civil War was waged between the newly established National Army and the Anti-Treaty IRA, which refused to recognise the state. The Civil War ended in victory for the government forces, with its opponents dumping their arms in May 1923. The Anti-Treaty political party, Sinn Féin, refused to take its seats in the Dáil, leaving the relatively small Labour Party as the only opposition party. In 1926, when Sinn Féin president Éamon de Valera failed to have this policy reversed, he resigned from Sinn Féin and led most of its membership into a new party, Fianna Fáil, which entered the Dáil following the 1927 general election. It formed the government after the 1932 general election, when it became the largest party.

De Valera abolished the oath of allegiance and embarked on an economic war with the UK. In 1937, he drafted a new constitution, which was adopted by a plebiscite in July of that year. The Free State came to an end with the coming into force of the new constitution on 29 December 1937, when the state took the name "Ireland".

Background

editThe Easter Rising of 1916 and its aftermath caused a profound shift in public opinion towards the republican cause in Ireland.[6] In the December 1918 General Election, the republican Sinn Féin party won a large majority of the Irish seats in the British parliament: 73 of the 105 constituencies returned Sinn Féin members (25 uncontested).[7] The elected Sinn Féin MPs, rather than take their seats at Westminster, set up their own assembly, known as Dáil Éireann (Assembly of Ireland). It affirmed the formation of an Irish Republic and passed a Declaration of Independence.[8] The subsequent War of Independence, fought between the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and British security forces, continued until July 1921 when a truce came into force. By this time the Parliament of Northern Ireland had opened, established under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, presenting the republican movement with a fait accompli and guaranteeing the British presence in Ireland.[9] In October negotiations opened in London between members of the British government and members of the Dáil, culminating in the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty on 6 December 1921.[10]

The Treaty allowed for the creation of a separate state to be known as the Irish Free State, with dominion status, within the then British Empire—a status equivalent to Canada.[10] The Parliament of Northern Ireland could, by presenting an address to the king, opt not to be included in the Free State, in which case a Boundary Commission would be established to determine where the boundary between them should lie.[11][12] Members of the parliament of the Free State would be required to take an oath of allegiance to the Constitution of the Free State and to declare that they would be "faithful" to the king (a modification of the oath taken in other dominions).[10]

The Dáil ratified the Treaty on 7 January 1922, causing a split in the republican movement.[13] A Provisional Government was formed, with Michael Collins as chairman.[14]

The Irish Free State was established on 6 December 1922, and the Provisional Government became the Executive Council of the Irish Free State, headed by W. T. Cosgrave as President of the Executive Council.[15] The following day, the Commons and the Senate of Northern Ireland passed resolutions "for the express purpose of opting out of the Free State".[16][e]

Governmental and constitutional structures

editThe Treaty established that the new state would be a constitutional monarchy, with the Governor-General of the Irish Free State as representative of the Crown. The Constitution of the Irish Free State made more detailed provision for the state's system of government, with a three-tier parliament, called the Oireachtas, made up of the king and two houses, Dáil Éireann and Seanad Éireann (the Irish Senate).

Executive authority was vested in the king, with the Governor-General as his representative. He appointed a cabinet called the Executive Council to "aid and advise" him. The Executive Council was presided over by a prime minister called the President of the Executive Council. In practice, most of the real power was exercised by the Executive Council, as the Governor-General was almost always bound to act on the advice of the Executive Council.

Representative of the Crown

editThe office of Governor-General of the Irish Free State replaced the previous Lord Lieutenant, who had headed English and British administrations in Ireland since the Middle Ages. Governors-General were appointed by the king initially on the advice of the British Government, but with the consent of the Irish Government. From 1927, the Irish Government alone had the power to advise the king whom to appoint.

Oath of Allegiance

editAs with all dominions, provision was made for an Oath of Allegiance. Within dominions, such oaths were taken by parliamentarians personally towards the monarch. The Irish Oath of Allegiance was fundamentally different. It had two elements; the first, an oath to the Free State, as by law established, the second part a promise of fidelity, to His Majesty, King George V, his heirs and successors. That second fidelity element, however, was qualified in two ways. It was to the King in Ireland, not specifically to the King of the United Kingdom. Secondly, it was to the king explicitly in his role as part of the Treaty settlement, not in terms of pre-1922 British rule. The Oath itself came from a combination of three sources, and was largely the work of Michael Collins in the Treaty negotiations. It came in part from a draft oath suggested prior to the negotiations by President de Valera. Other sections were taken by Collins directly from the Oath of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), of which he was the secret head. In its structure, it was also partially based on the form and structure used for 'Dominion status'.[19]

Although 'a new departure', and notably indirect in its reference to the monarchy, it was criticised by nationalists and republicans for making any reference to the Crown, the claim being that it was a direct oath to the Crown, a fact arguably incorrect by an examination of its wording, but in 1922 Ireland and beyond, many argued that the fact remained that as a dominion the King (and therefore the British) was still Head of State and that was the practical reality that influenced public debate on the issue. The Free State was not a republic. The Oath became a key issue in the resulting Irish Civil War that divided the pro and anti-treaty sides in 1922–23.

Irish Civil War

editThe compromises contained in the agreement caused the civil war in the 26 counties in June 1922 – April 1923, in which the pro-Treaty Provisional Government defeated the anti-Treaty Republican forces. The latter were led, nominally, by Éamon de Valera, who had resigned as President of the Republic on the treaty's ratification. His resignation outraged some of his own supporters, notably Seán T. O'Kelly, the main Sinn Féin organiser. On resigning, he then sought re-election but was defeated two days later on a vote of 60–58. The pro-Treaty Arthur Griffith followed as President of the Irish Republic. Michael Collins was chosen at a meeting of the members elected to sit in the House of Commons of Southern Ireland (a body set up under the Government of Ireland Act 1920) to become Chairman of the Provisional Government of the Irish Free State in accordance with the Treaty. The general election in June gave overwhelming support for the pro-Treaty parties. W. T. Cosgrave's Crown-appointed Provisional Government effectively subsumed Griffith's republican administration with the death of both Collins and Griffith in August 1922.[20]

"Freedom to achieve freedom"

editGovernance

editThe following were the principal parties of government of the Free State between 1922 and 1937:

- Cumann na nGaedheal under W. T. Cosgrave (1922–32)

- Fianna Fáil under Éamon de Valera (1932–37)

Constitutional evolution

editMichael Collins described the Treaty as "the freedom to achieve freedom". In practice, the Treaty offered most of the symbols and powers of independence. These included a functioning, if disputed, parliamentary democracy with its own executive, judiciary and written constitution which could be changed by the Oireachtas. Although an Irish republic had not been on offer, the Treaty still afforded Ireland more internal independence than it had possessed in over 400 years, and far more autonomy than had ever been hoped for by those who had advocated for Home Rule.[21]

However, a number of conditions existed:

- The king remained king in Ireland;

- Britain retained the so-called strategic Treaty Ports on Ireland's south and north-west coasts which were to remain occupied by the Royal Navy;

- Prior to the passage of the Statute of Westminster, the UK government continued to have a role in Irish governance. Officially the representative of the king, the Governor-General also received instructions from the British Government on his use of the Royal Assent, namely a Bill passed by the Dáil and Seanad could be Granted Assent (signed into law), Withheld (not signed, pending later approval) or Denied (vetoed). The letters patent to the first Governor-General, Tim Healy, explicitly named Bills that were to be rejected if passed by the Dáil and Seanad, such as any attempt to abolish the Oath. In the event, no such Bills were ever introduced, so the issue was moot.

- As with the other dominions, the Free State had a status of association with the UK rather than being completely legally independent from it. However, the meaning of 'Dominion status' changed radically during the 1920s, starting with the Chanak crisis in 1922 and quickly followed by the directly negotiated Halibut Treaty of 1923. The 1926 Imperial Conference declared the equality [including the UK] of all member states of the Commonwealth. The Conference also led to a reform of the king's title, given effect by the Royal and Parliamentary Titles Act 1927, which changed the king's royal title so that it took account of the fact that there was no longer a United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The king adopted the following style by which he would be known in all of his empire: By the Grace of God, of Great Britain, Ireland and the British Dominions beyond the Seas King, Defender of the Faith, Emperor of India. That was the king's title in Ireland just as elsewhere in his empire.[22]

- In the conduct of external relations, the Free State tried to push the boundaries of its status as a Dominion. It 'accepted' credentials from international ambassadors to Ireland, something no other dominion up to then had done. It registered the treaty with the League of Nations as an international document, over the objections of the United Kingdom, which saw it as a mere internal document between a dominion and the United Kingdom. Entitlement of citizenship of the Free State was defined in the Irish Free State Constitution, but the status of that citizenship was contentious. One of the first projects of the Free State was the design and production of the Great Seal of Saorstát Éireann which was carried out on behalf of the Government by Hugh Kennedy.

The Statute of Westminster of 1931, embodying a decision of an Imperial Conference, enabled each dominion to enact new legislation or to change any extant legislation, without resorting to any role for the British Parliament that may have enacted the original legislation in the past. It also removed Westminster's authority to legislate for the Dominions, except with the express request and consent of the relevant Dominion's parliament. This change had the effect of making the dominions, including the Free State, de jure independent nations—thus fulfilling Collins' vision of having "the freedom to achieve freedom".

The Free State symbolically marked these changes in two mould-breaking moves soon after winning internationally recognised independence:

- It sought, and got, the king's acceptance to have an Irish minister, to the complete exclusion of British ministers, formally advise the king in the exercise of his powers and functions as king in the Irish Free State. This gave the President of the Executive Council the right to directly advise the king in his capacity as His Majesty's Irish Prime Minister. Two examples of this are the signing of a treaty between the Irish Free State and the Portuguese Republic in 1931, and the act recognising the abdication of King Edward VIII in 1936 separately from the recognition by the British Parliament.

- The unprecedented replacement of the use of the Great Seal of the Realm and its replacement by the Great Seal of Saorstát Éireann, which the king awarded to the Irish Free State in 1931. (The Irish Seal consisted of a picture of King George V enthroned on one side, with the Irish state harp and the words Saorstát Éireann on the reverse. It is now on display in the Irish National Museum, Collins Barracks in Dublin.)

When Éamon de Valera became President of the Executive Council (prime minister) in 1932 he described Cosgrave's ministers' achievements simply. Having read the files, he told his son, Vivion, "they were magnificent, son".

The Statute of Westminster allowed de Valera, on becoming President of the Executive Council (February 1932), to go even further. With no ensuing restrictions on his policies, he abolished the Oath of Allegiance (which Cosgrave intended to do had he won the 1932 general election), the Seanad, university representation in the Dáil, and appeals to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.

One major policy error occurred in 1936 when he attempted to use the abdication of King Edward VIII to abolish the crown and governor-general in the Free State with the "Constitution (Amendment No. 27) Act". He was advised by senior law officers and other constitutional experts that, as the crown and governor-generalship existed separately from the constitution in a vast number of acts, charters, orders-in-council, and letters patent, they both still existed. A second bill, the "Executive Powers (Consequential Provisions) Act, 1937" was quickly introduced to repeal the necessary elements. De Valera retroactively dated the second act back to December 1936.

Currency

editThe new state continued to use the Pound sterling from its inception; there is no reference in the Treaty or in either of the enabling Acts to currency.[23] Nonetheless, and within a few years, the Dáil passed the Coinage Act, 1926 (which provided for a Saorstát [Free State] coinage) and the Currency Act, 1927 (which provided inter alia for banknotes of the Saorstát pound). The new Saorstát pound was defined by the 1927 Act to have exactly the same weight and fineness of gold as was the sovereign at the time, making the new currency pegged at 1:1 with sterling. The State circulated its new national coinage in 1928, marked Saorstát Éireann and a national series of banknotes. British coinage remained acceptable in the Free State at an equal rate. In 1937, when the Free State was superseded by Ireland (Éire), the pound became known as the "Irish pound" and the coins were marked Éire.

Foreign policy

editIreland joined the League of Nations on 10 September 1923.[24] It would also participate in the Olympics sending its first team to the 1924 Summer Olympics held in Paris.[25] They would send further teams to the 1928 Summer Olympics and the 1932 Summer Olympics.[26]

According to Gerard Keown, by 1932 much had been achieved in the quest for an independent foreign policy.[27]

The Irish Free State was an established element in the European system and a member of the League of Nations. It had blazed a trail in asserting the rights of the dominions to their own foreign policy, in the process establishing full diplomatic relations with the United States, France, Belgium, Germany, and the Holy See. It was concluding its own political and commercial treaties and using the apparatus of international relations to pursue its interests. It had received the accolade of election to a non-permanent seat on the council of the League of Nations and asserted its full equality with Britain and the other dominions within the Commonwealth.

By contrast, the military was drastically reduced in size and scope, with its budget cut by 82% from 1924 to 1929. The active duty forces were reduced from 28,000 men to 7,000. Cooperation with London was minimal.[28][29]

Demographics

editBirth rate

editAccording to one report, in 1924, shortly after the Free State's establishment, the new dominion had the "lowest birth-rate in the world". The report noted that amongst countries for which statistics were available (Ceylon, Chile, Japan, Spain, South Africa, the Netherlands, Canada, Germany, Australia, the United States, Britain, New Zealand, Finland, and the Irish Free State), Ceylon had the highest birth rate at 40.8 per 1,000 while the Irish Free State had a birth rate of just 18.6 per 1,000.[30]

Cultural outlook

editIrish society during this period was extremely Roman Catholic, with Roman Catholic thinkers promoting anti-capitalist, anti-communist, anti-Protestant, anti-Masonic, and antisemitic views in Irish society.[citation needed] Through the works of priests such as Edward Cahill, Richard Devane, and Denis Fahey, Irish society saw capitalism, individualism, communism, private banking, the promotion of alcohol, contraceptives, divorce, and abortion as the pursuits of the old 'Protestant-elite' and Jews, with their efforts combined through the Freemasons. Denis Fahey described Ireland as "the third most Masonic country in the world" and saw this alleged order as contrary to the creation of an independent Irish State.[31]

After the Irish Free State

edit1937 Constitution

editIn 1937 the Fianna Fáil government presented a draft of an entirely new Constitution to Dáil Éireann. An amended version of the draft document was subsequently approved by the Dáil. A plebiscite was held on 1 July 1937, which was the same day as the 1937 general election, when a relatively narrow majority approved it. The new Constitution of Ireland (Bunreacht na hÉireann) repealed the 1922 Constitution, and came into effect on 29 December 1937.[32]

The state was named Ireland (Éire in the Irish language), and a new office of President of Ireland was instituted in place of the Governor-General of the Irish Free State. The new constitution claimed jurisdiction over all of Ireland while recognising that legislation would not apply in Northern Ireland (see Articles 2 and 3). Articles 2 and 3 were reworded in 1998 to remove jurisdictional claim over the entire island and to recognise that "a united Ireland shall be brought about only by peaceful means with the consent of a majority of the people, democratically expressed, in both jurisdictions in the island".

With regard to religion, a section of Article 44 included the following:

The State recognises the special position of the Holy Catholic Apostolic and Roman Church as the guardian of the Faith professed by the great majority of the citizens. The State also recognises the Church of Ireland, the Presbyterian Church in Ireland, the Methodist Church in Ireland, the Religious Society of Friends in Ireland, as well as the Jewish Congregations and the other religious denominations existing in Ireland at the date of the coming into operation of this Constitution.

Following a referendum, this section was removed in 1973. After the setting up of the Free State in 1923, unionism in the south largely came to an end.

The 1937 Constitution saw a notable ideological slant to the changes of the framework of the State in such a way as to create one that appeared to be distinctly Irish. This was done so by implementing corporatist policies (based on the concepts of the Roman Catholic Church, as Catholicism was perceived to be deeply imbedded with the perception of Irish identity). A clear example of this is the model of the reconstituted Seanad Éireann (the Senate), which operates based on a system of vocational panels, along with a list of appointed nominating industry bodies, a corporatist concept (seen in Pope Pius XI's 1931 encyclical Quadragesimo anno). Furthermore, Ireland's main political parties; Fine Gael, Fianna Fáil and Labour, all had an inherently corporatist outlook.[33][34][35][36][37][38] The government was the subject of intense lobbying by leading Church figures throughout the 1930s in calling for reform of the State's framework. Much of this was reflected in the new 1937 Constitution.[39]

See also

edit- Irish states since 1171

- Series A Banknotes – first issued by the Irish Free State in 1928

Notes

edit- ^ The United Kingdom and the Irish Free State considered each other as states with equal status within the British Empire. However, for other sovereign states (i.e. United States, France, Brazil, Japan, Ethiopia, etc) and the international community as a whole (i.e League of Nations) the term Dominion was very ambiguous. At the time of the founding of the League of Nations in 1924, the League Covenant made provision for the admission of any "fully self-governing state, Dominion, or Colony", the implication being that "Dominion status was something between that of a colony and a state"

- ^ With the Statute of Westminster 1931 the ambiguity is dispelled for the international community with three British Dominions (Irish Free State, Canada and Union of South Africa), being recognized as sovereign states in their own right. Unlike what happened in Australia in 1942 and New Zealand in 1947, the whole statute was applied to the Dominion of Canada, the Irish Free State, and the Union of South Africa without the need for any acts of ratification.

- ^ National language

- ^ Co-official and the most widely spoken language

- ^ Whether the Treaty, or the Irish Free State (Agreement) Act 1922 which gave it force of law, had the legal effect under United Kingdom law of making Northern Ireland a part of the Irish Free State for one or two days is a point legal writers have disagreed on. One writer has argued that the terms of the Treaty legally applied only to the 26 counties, and the government of the Free State never had any powers—even in principle—in Northern Ireland.[17] Another writer has argued that on the day it was established the jurisdiction of the Free State was the island of Ireland.[18] A 1933 court decision in Ireland took the latter view.[18] The de facto position was that Northern Ireland was treated as at all times being within the United Kingdom.

References

edit- ^ Officially adopted in July 1926. O'Day, Alan (1987). Alan O'Day (ed.). Reactions to Irish nationalism. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-907628-85-9. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ "1926 Census Vol.3 Table 1A" (PDF). Central Statistics Office. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2020. (1861–1926)

- ^ "Census of Population 1936" (PDF). Dublin: The Stationery Office. 1938. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ "Saorstat Eireann". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Archived from the original on 30 August 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ "The Irish War of Independence – A Brief Overview – The Irish Story". Archived from the original on 1 September 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ Marie Coleman, The Republican Revolution, 1916–1923, Routledge, 2013, chapter 2 "The Easter Rising", pp. 26–28. ISBN 140827910X

- ^ Ferriter, Diarmuid (2004). The Transformation of Ireland, 1900–2000. Profile. p. 183. ISBN 1-86197-307-1. Archived from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ J. J. Lee, Ireland 1912–1985 Politics and Society p. 40, Cambridge University Press (1989) ISBN 978-0521266482

- ^ Garvin, Tom: The Evolution of Irish Nationalist Politics : p. 143 Elections, Revolution and Civil War Gill & Macmillan (2005) ISBN 0-7171-3967-0

- ^ a b c Lee (1989), p. 50

- ^ Lee (1989), p. 51

- ^ Martin, Ged (1999). "The Origins of Partition". In Anderson, Malcolm; Bort, Eberhard (eds.). The Irish Border: History, Politics, Culture. Liverpool University Press. p. 68. ISBN 0853239517. Archived from the original on 29 January 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

It is certainly true that the Treaty went through the motions of including Northern Ireland within the Irish Free State while offering it the provision to opt out

- ^ Lee (1989), pp. 53–54

- ^ Lee (1989), pp. 54–55

- ^ Lee (1989), p. 94

- ^ Fanning, Ronan (2013). Fatal Path: British Government and Irish Revolution 1910-1922. London: Faber and Faber. p. 342. ISBN 978-0-571-29739-9.

- ^ Morgan, Austen (2000). The Belfast Agreement: A Practical Legal Analysis (PDF). The Belfast Press. pp. 66, 68. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2015.

it was legally clear that the treaty, and the associated provisional parliament and government, applied only to the 26 counties...[Article 11] implied politically – but not legally – that the Irish Free State had some right to Northern Ireland. But partition was acknowledged expressly in the treaty...following the text of article 12, [the address] requested that the powers of the parliament and government of the Irish Free State should no longer extend to Northern Ireland. This does not mean they had so extended on 6 December 1922.

- ^ a b Harvey, Alison (March 2020). "A Legal Analysis of Incorporating Into UK Law the Birthright Commitment under the Belfast (Good Friday) Agreement 1998" (PDF). Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission and the Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission. para. 91. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

The jurisdiction of the Free State was the island of Ireland. The Northern Ireland Parliament gave notice, as it was entitled to do, that it did not wish to come under the jurisdiction of the Free State. In Re Logue [1933] 67 ILTR 253 it was held that, because the notice took effect after the Constitution of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann) had come into operation, most of those domiciled in Northern Ireland had become Irish citizens under Article 3 of the Constitution of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Éireann).

- ^ Coffey, Donal K. (2016). "The Commonwealth and the Oath of Allegiance Crisis: A Study in Inter-War Commonwealth Relations". The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 44 (3): 492–512. doi:10.1080/03086534.2016.1175735.

- ^ Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green–The Irish Civil War: A History of the Irish Civil War, 1922–1923 (Gill & Macmillan, 2004) online.

- ^ Michael Gallagher, "The changing constitution." in Politics in the Republic of Ireland (Routledge, 2009) pp.94-130.

- ^ Long after the Irish Free State had ceased to exist, when Elizabeth II ascended the Throne, the Royal Titles Act 1953[1] Archived 30 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine was passed, as were other Acts concerning her Style in other parts of the Empire. Until then the British monarch had only one style. The king was never simply the "King of Ireland" or the "King of the Irish Free State".

- ^ Except perhaps by inference: the Treaty assigned to the Irish Free State the same status in the Empire as Canada and the latter had already [1851—59] replaced the British Pound (with the Canadian Dollar).

- ^ "Commemoration Programme". National Archives. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ O'Hanlon, Oliver (22 July 2024). "How did the first Irish Olympics team fare in Paris 100 years ago?". RTE.ie. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ "Ireland (IRL)". Olympedia. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ Gerard Keown, First of the Small Nations: The Beginnings of Irish Foreign Policy in the Interwar Years, 1919–1932 (Oxford UP, 2016) p. 243 online.

- ^ Eunan O'Halpin, Defending Ireland: The Irish State and Its Enemies since 1922 (2000) pp.87, 92-93.

- ^ Denis Gwynn,The Irish Free State, 1922-1927 (Macmillan 1928);. pp.176–190 online.

- ^ "Otautau Standard and Wallace County Chronicle, Vol. XVIX, Iss. 971, 11 March 1924, p. 1". Archived from the original on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2009.

- ^ Beatty, Aidan (30 December 2021). "The Problem of Capitalism in Irish Catholic Social Thought, 1922–1950". Études irlandaises (46–2): 43–68. doi:10.4000/etudesirlandaises.11722. ISSN 0183-973X. S2CID 245340404.

- ^ See Donal K. Coffey, Drafting the Irish Constitution, 1935–1937: Transnational Influences in Interwar Europe (Springer, 2018) online.

- ^ Adshead, Maura (2003). Ireland as a Catholic Corporatist State: A Historical Institutional Analysis of Healthcare in Ireland. Department of Politics and Public Administration, University of Limerick. ISBN 978-1-874653-74-5.

- ^ McGinley, Jack (2000). Neo-corporatism, New Realism and Social Partnership in Ireland 1970–1999. Trinity College.

- ^ Allen, Kieran (1995). Fianna Fail and Irish Labour Party: From Populism to Corporatism. Pluto Press.

- ^ Tovey, Hilary; Share, Perry (2003). A Sociology of Ireland. Gill & Macmillan Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7171-3501-1.

- ^ Moylan, M. T. C. (1983). Corporatist Developments in Ireland.

- ^ "New Seanad could cause turbulence". The Irish Times. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ Morrissey, Thomas; Morrissey, Thomas J. (2021). The Ireland of Edward Cahill SJ 1868–1941: A Secular or a Christian State?. Messenger Publications. ISBN 978-1-78812-430-0.

Further reading

edit- Carroll, J. T. (1975). Ireland in the War Years 1939–1945. David and Charles. ISBN 9780844805658.

- Coogan, Tim Pat (1993). De Valera: Long Fellow, Long Shadow. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 9780091750305. published as Eamon de Valera: The Man Who Was Ireland (New York, 1993)

- Coogan, Tim Pat (1990). Michael Collins. Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-174106-8.

- Corcoran, Donal. "Public policy in an emerging state: The Irish Free State 1922-25." Irish Journal of Public Policy 1.1 (2009). online

- Dwyer, T. Ryle (2006). Big Fellow, Long Fellow: A Joint Biography of Collins and De Valera. Gill Books. ISBN 0717140849. excerpt and text search

- Dwyer, T. Ryle (1982). De Valera's Finest Hour 1932–59.

- Fanning, Ronan. Éamon de Valera: A Will to Power (2016)

- Foster, R. F. Modern Ireland, 1600-1972 (1989) online

- Girvin, Brian. "Beyond Revisionism? Some Recent Contributions to the Study of Modern Ireland." The English Historical Review 124#506, 2009, pp. 94–107. online

- Gwynn, Denis. The Irish Free State, 1922-1927 (Macmillan 1928); detailed coverage.online

- Keown, Gerard. First of the Small Nations: The Beginnings of Irish Foreign Policy in the Inter-war Years, 1919-1932 (Oxford University Press, 2016). online

- Kissane, Bill. "Eamon De Valera and the Survival of Democracy in Inter-War Ireland". Journal of Contemporary History (2007). 42 (2): 213–226. online

- Lee, J. J. Ireland, 1912-1985: politics and society (Cambridge University Press, 1989) online.

- McCardle, Dorothy (January 1999). The Irish Republic. Wolfhound Press. ISBN 0-86327-712-8.

- O'Halpin, Eunan. Defending Ireland: The Irish State and Its Enemies since 1922 (2000); on the military; online

Primary sources

edit- Pakenham Frank. Peace by Ordeal: An Account, from first-hand sources, of the Negotiation and Signature of the Anglo-Irish Treaty 1921 (1921) online