The scuttling of the French fleet at Toulon was orchestrated by Vichy France on 27 November 1942 to prevent Nazi German forces from seizing it.[2] After the Allied invasion of North Africa, the Germans invaded the territory administered by Vichy under the Armistice of 1940.[3] The Vichy Secretary of the Navy, Admiral François Darlan, defected to the Allies, who were gaining increasing support from servicemen and civilians.[4] His replacement, Admiral Gabriel Auphan,[5] guessed correctly that the Germans intended to seize the large fleet at Toulon (even though this was explicitly forbidden in the Franco-Italian armistice and the French-German armistice),[6][7][8] and ordered it scuttled.[9]

| Scuttling of the French fleet at Toulon | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the German occupation of Vichy France | |||||||

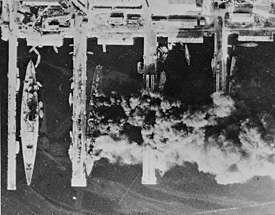

Strasbourg, Colbert, Algérie, and Marseillaise[1] | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Johannes Blaskowitz | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

164 vessels

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

77 vessels

3 destroyers (disarmed) 4 submarines (badly damaged) 39 small ships | 1 wounded[citation needed] | ||||||

The Germans began Operation Anton but the French naval crews used subterfuge to delay them until the scuttling was complete.[10] Anton was judged a failure,[11] with the capture of 39 small ships, while the French destroyed 77 vessels; several submarines escaped to French North Africa.[12] It marked the end of Vichy France as a credible naval power[13] and marked the destruction of the last political bargaining chip it had with Germany.[14][15]

Context

editAfter the Fall of France and the Armistice of 22 June 1940, France was divided into two zones, one occupied by the Germans, and the zone libre (free zone).[16] Officially, both zones were administered by the Vichy regime. The armistice stipulated that the French fleet would be largely disarmed and confined to its harbours under French control, but the French fleet did cooperate with Nazi Germany although the French retained ultimate operational control over their ships.[6][17][18] The Allies were concerned that the fleet, which included some of the most advanced warships of the time, might fall into German hands (especially the British who considered it to be a life-or-death matter)[19][20] and the British attacked the French fleet at Mers-el-Kébir on 3 July 1940 and at the Battle of Dakar on 23 September 1940.[21][22]

On 8 November 1942 the Allies invaded French North Africa in Operation Torch. It may be that General Dwight Eisenhower, with the support of President of the United States Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, made a secret agreement with Admiral Darlan to give him control of French North Africa if he defected to the Allies.[23][4] An alternative view is that Darlan was an opportunist and switched sides for self-advancement, thus becoming titular head of French North Africa.[24] Following the Allied invasion of French North Africa, Adolf Hitler ordered Case Anton, the occupation of Vichy France and reinforced German forces in Africa.

Prelude

editPolitical aspect

editBeginning 11 November 1942 negotiations took place between Germany and Vichy France. The resolution was that Toulon should remain a "stronghold" under Vichy control and defended against the Allies and "French enemies of the government of the Maréchal".[25] Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, commander of the Kriegsmarine, believed that Vichy French Navy officers would fulfill their duty under the armistice to not let the ships fall into the hands of a foreign nation.

Raeder was led to believe that the Germans intended to use anti-British sentiment among French sailors to get them to side with the Italians. Hitler in fact intended to seize the fleet and have German sailors capture the French ships and turn them over to Italy; German officers privy to this plan objected but Hitler ignored them and gave orders to implement the plan on 19 November.[citation needed]

On 11 November, as German and Italian troops encircled Toulon, the Vichy Secretary of the Navy, Admiral Gabriel Auphan, ordered Admirals Jean de Laborde and André Marquis to:

- Oppose, without spilling blood, entry of foreign troops to any establishment, airbase or buildings of the French Navy

- Similarly oppose foreign troops attempting to board any ships of the fleet and resolve Matters through local negotiation

- If the above proved impossible, to scuttle the ships

Engineers had the initial orders to scuttle the ships by capsizing them. The order was then modified, in the interest of recovering the ships after the war, to sinking them on an even keel. On 15 November, Laborde met with Marshal Philippe Pétain and Auphan. In private, Auphan tried to persuade Laborde to set sail and join the Allies; Laborde refused to obey anything short of a formal order from the French government, and Auphan resigned shortly thereafter.

Technical and tactical aspect

editOn the French side, as a token of goodwill towards the Germans, coastal defences were strengthened to safeguard Toulon from an attack from the sea by the Allies. These preparations included preparations to scuttle the fleet, in case the Allies succeeded in landing. French forces commanded by Admiral Jean de Laborde included the "High Seas Fleet" composed of the 38 most modern and powerful warships, and Admiral André Marquis, préfet maritime commanded a total of 135 ships, either in armistice custody or under repair.

Under the armistice, French ships were supposed to have almost empty fuel tanks; in fact, by falsifying reports and tampering with gauges, their crews had managed to store enough fuel to reach North Africa. One of the cruisers, Jean de Vienne, was in drydock, helpless. After the Germans required the remnants of the French Army to disband, French sailors had to man coast defence artillery and anti-aircraft guns, which made it impossible to swiftly gather the crews and get the ships quickly under way.

Crews were initially hostile to the Allied invasion but out of the general anti-German sentiment and as rumours about Darlan's defection circulated, this stance evolved into support for De Gaulle. The crews of the Strasbourg, Colbert, Foch and Kersaint, notably, started chanting "Long live De Gaulle! Set sail!"[This quote needs a citation] On 12 November, Admiral Darlan further escalated tensions by calling for the fleet to defect and join the Allies.[4][24]

Vichy military authorities lived in fear of a coup de main organised by the British or by the Free French. The population of Toulon, defiant of the Germans, mostly supported the Allies; the soldiers and officers were hostile to the Italians who were seen as "illegitimate victors" and duplicitous. The fate of the fleet, in particular, seemed dubious. Between the 11th and the 26th, numerous arrests and expulsions took place. The French admirals, Laborde and Marquis, ordered their subordinates to take a pledge of allegiance to the regime. Two senior officers, Humbertand and capitaine de vaisseau Pothuau, refused. The crews were first kept aboard their ships, and when they were allowed ashore the Service d'ordre légionnaire monitored all suspected targets of the Resistance.

Operation Lila

editThe objective of Operation Lila was to capture the units of the French fleet at Toulon intact. The 7th Panzer Division, augmented with four combat groups including two armoured groups and a motorcycle battalion from the 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich, were entrusted with the mission. To prevent French naval units from scuttling themselves, Marinedetachment Gumprich was assigned to one of the groups.[26]

The operation was initiated by the Germans on 19 November 1942, to be completed by 27 November. German forces were to enter Toulon from the east, capturing Fort Lamalgue, headquarters of Admiral Marquis and the Mourillon arsenal; and from the west, capturing the main arsenal and the coastal defenses. German naval forces cruised off the harbor to engage any ships attempting to flee, and laid naval mines.

The combat groups entered Toulon at 4 a.m. on 27 November and made for the harbour, meeting only weak and sporadic resistance. At 4 a.m. the Germans entered Fort Lamalgue and arrested Marquis, but failed to prevent his chief of staff, Contre-Admiral Robin, from calling the chief of the arsenal, Contre-Admiral Dornon. The attack came as a complete surprise to Vichy officers, but Dornon transmitted the order to scuttle the fleet to Admiral Laborde aboard the flagship Strasbourg. Laborde was taken aback by the German operation, but transmitted orders to prepare for scuttling, and to fire on any unauthorised personnel approaching the ships.[27][23]

Twenty minutes later, German troops entered the arsenal and started machine-gunning the French submarines. Some of the submarines set sail to scuttle in deeper water. Casabianca left her moorings, snuck out of the harbour and dove at 5:40 a.m., escaping to Algiers.[28] The German main force got lost in the arsenal and was behind schedule by one hour; when they reached the main gates of the base, the sentries pretended to need paperwork, to delay the Germans without engaging in an open fight. At 5:25 a.m., German tanks finally rolled through, and Strasbourg immediately transmitted the order "Scuttle! Scuttle! Scuttle!" by radio, visual signals and dispatch boat. French crews evacuated, and scuttling parties started preparing demolition charges and opening sea valves on the ships.

At 6:45 a.m. fighting broke out around Strasbourg and Foch, killing a French officer and wounding five sailors. When naval guns started engaging the German tanks, the Germans attempted to negotiate; a German officer demanded that Laborde surrender his ship, to which the admiral answered that the ship was already sunk.

As Strasbourg settled on the bottom, her captain ordered demolition charges ignited, which destroyed the armaments and vital machinery, and ignited her fuel stores. Strasbourg was a total loss.[29] A few minutes later the cruiser Colbert exploded. The German party attempting to board the cruiser Algérie heard the explosions and tried to persuade her crew that scuttling was forbidden under the armistice provisions. However, the demolition charges were detonated, and the ship burned for twenty days.[citation needed]

Meanwhile, the captain of the cruiser Marseillaise ordered his ship capsized and demolition charges set. German troops requested permission to come aboard; when this was denied, they did not attempt to board. The ship sank and exploded, burning for seven days.[citation needed]

German troops forcibly boarded the cruiser Dupleix, put her crew out of the way, and closed her open sea valves. The ship's captain, Moreau, ordered the scuttling charges in the main turrets lit with shortened fuses and when they exploded and fires took hold, ordered a final evacuation. French and Germans alike fled the vessel. Explosions from the ship's torpedo stores destroyed the vessel, which burned for ten days.[30]

The cruiser Jean de Vienne, in drydock, was boarded by German troops, who disarmed the demolition charges, but the open sea valves flooded the ship. She sank, blocking the drydock. In another drydock, the captain of the damaged Dunkerque, which had been heavily damaged by the British in the attack on Mers-el-Kébir, at first refused orders to scuttle, but was persuaded by his colleague in the nearby cruiser La Galissonnière to follow suit. The crew opened the holes caused by British torpedo attacks to sink the ship, and demolition charges destroyed her vital machinery. As Dunkerque exploded, La Galissonnière reproduced the manoeuvre executed by Jean de Vienne.

Officers of the battleship Provence and the seaplane carrier Commandant Teste managed to delay German officers with small talk until their ships were completely sunk.[29]

Similar scenes occurred with the destroyers and submarines. Germans already had come aboard the submarine Henri Poincaré by the time her crew opened her seacocks to scuttle her, and the French crewmen and Germans jostled one another as the French abandoned ship and the enraged Germans rushed below to try to prevent her from sinking.[31] Unfamiliar with submarines, the Germans were unsuccessful and narrowly avoided drowning as they evacuated the sinking submarine..[31]

The Germans eventually seized three disarmed destroyers, four badly damaged submarines, three civilian ships, and the remains of two obsolete battleships of no combat value, the semi-dreadnought Condorcet and the disarmed former Jean Bart, renamed Océan in 1936 and hulked for use as an accommodation ship.

Aftermath

editOperation Lila was a failure.[citation needed] The French destroyed 77 vessels, including 3 battleships, 7 cruisers, 15 destroyers, 13 torpedo boats, 6 sloops, 12 submarines, 9 patrol boats, 19 auxiliary ships, 1 school ship, 28 tugs, and 4 cranes.[12][32] 39 small ships were captured, most of them sabotaged and disarmed.[33][32] Some of the major ships were ablaze for several days, and oil polluted the harbour so badly that it would not be possible to swim there for two years.[34]

As was to be expected, the scuttling ended friendly naval cooperation between the Axis and Vichy France and Germany absorbed whatever naval assets Vichy France had left.[18]

Several submarines ignored orders to scuttle and chose to defect to French North Africa: Casabianca and Marsouin reached Algiers, Glorieux reached Oran. Iris reached Barcelona. Vénus was scuttled in the entrance of Toulon harbour. One auxiliary surface ship, Leonor Fresnel, managed to escape and reach Algiers. General Charles de Gaulle heavily criticised the Vichy admirals for not ordering the fleet to flee to Algiers. The Vichy regime lost its last token of power, as well as its credibility with the Germans, with the fleet.

While the German Naval War Staff were disappointed, Adolf Hitler took a different perspective. He had little use for capital ships and other large naval vessels, especially after the sinking of the Bismarck, and so was satisfied considering the elimination of the French fleet to have sealed the success of Case Anton.[26] The French fleet was annihilated and only a handful of small ships escaped to assist the Allied forces for the rest of the war.

The scuttling of the fleet did remove British and Allied strategic concerns about the possibility of it falling into German hands[16] and allowed them to focus their naval resources elsewhere;[35][36] although the British did try at first to have the French fleet defect to them but its destruction was in the end equally acceptable to them.[37] Conversely, the loss of the French ships also had disastrous results in relation to Italian naval strategy and ambitions as the Regia Marina had envisioned acquiring part of the French fleet for itself; thus, the event strained the relations between Vichy France and Fascist Italia almost to the breaking point.[38]

A year later, the Italian naval fleet did what de Gaulle wished the Vichy French had done. They set sail for North Africa after the Italian Armistice in 1943. Almost all major warships of the Regia Marina escaped Italy and were available for Italy after the end of World War II.[39][40] France had to rebuild its whole navy after the war.[32]

Most of the French light cruisers were salvaged by the Italians, either to restore them as fighting ships or for scrap. The cruisers Jean de Vienne and La Galissonnière were renamed FR11 and FR12, respectively, but their repair was prevented by Allied bombing and their use would have been unlikely, given the Italians' chronic shortage of fuel. Even the light destroyer Le Hardi (renamed FR37) and another four of the same class as Le Hardi were salvaged: FR32 (ex-Corsaire), FR33 (ex-Epée), FR34 (ex-Lansquenet), FR35 (ex-Fleuret).[9]

The main guns from the scuttled battleship Provence were later removed and used in a former French turret battery at Saint-Mandrier-sur-Mer, guarding the approaches to Toulon, to replace original fortress guns, sabotaged by their French crews.[29] Mounting four 340 mm (13 in) guns, in 1944 this fortification duelled with numerous Allied battleships for over a week before being silenced during Operation Dragoon.[41][42]

Ships sunk

edit|

Battleships

Seaplane tender Sloops

|

Destroyers |

Heavy cruisers Torpedo-boats |

Light cruisers Submarines

|

See also

edit- Attack on Mers-el-Kébir, a British attempt to destroy the French fleet

- Scuttling of the Peruvian fleet at El Callao, during the War of the Pacific

- Scuttling of the German fleet at Scapa Flow, a similar incident involving the German fleet after World War I

Notes and references

edit- ^ Position des bâtiments au matin du 27 novembre 1942, Netmarine.net (in French)

- ^ Auphan & Mordal 2016, p. 267, Chapter 22. Tragedy at Toulon and Bizerte.

- ^ Murray, Nicholas (1 June 2017). Lord, Carnes (ed.). "How the War Was Won: Air-Sea Power and Allied Victory in World War II, by Phillips PaysonO'Brien". Naval War College Review. 70 (3). Washington, D.C., United States: Naval War College: 148–149. ISSN 0028-1484. LCCN 75617787. OCLC 01779130. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Frank, Arthur L. (1 April 1973). "Negotiating the 'Deal with Darlan'". Journal of Contemporary History. 8 (2). Thousand Oaks, California, United States: SAGE Publications: 81–117. doi:10.1177/002200947300800205. ISSN 0022-0094. JSTOR 259995. LCCN 66009877. OCLC 1783199. S2CID 159589846.

- ^ Roberts, Priscilla (2012). "Auphan, Paul Gabriel (1894—1982)". In Tucker, Spencer C.; Pierpaoli Jr., Paul G.; Osborne, Eric W.; O'Hara, Vincent P. (eds.). World War II at Sea: An Encyclopedia. Vol. I. Santa Barbara, California, United States: ABC-CLIO. p. 66. ISBN 9781598844573 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Auphan & Mordal 2016, p. 115, Chapter 12. The Misunderstanding Over Article 8.

- ^ Upward 2016, pp. 170–171, Chapter Four: Collaboration.

- ^ MacGalloway, Niall (1 February 2018). Starkey, David J.; Barnard, Michaela (eds.). "The French fleet and the Italian occupation of France, 1940–1942". International Journal of Maritime History. 30 (1). International Maritime Economic History Association/SAGE Publishing: 139–143. doi:10.1177/0843871417746892. ISSN 0843-8714. OCLC 21102214. S2CID 158144591.

- ^ a b Gilbert, Martin (2014). "28. The turn of the tide for the Allies, Winter 1942". The Second World War: A Complete History. Rosetta Books. p. 468. ISBN 9780795337291 – via Google Books.

- ^ Black, Henry (1 April 1970). "Hopes, fears and premonitions: The French Navy, 1949-1942". Southern Quarterly. 8 (3). Hattiesburg, Mississippi, United States: University of Southern Mississippi: 309–332. ISSN 0038-4496.

- ^ Vaisset, Thomas; Vial, Philippe (1 September 2020). Viant, Julien (ed.). "Success or failure? The divided memory of the sabotage of Toulon". Inflexions. 45 (3). Paris, France: French Army/Cairn.info: 45–60. doi:10.3917/infle.045.0045. ISSN 1772-3760. S2CID 226424361.

- ^ a b Symonds 2018, p. 363, 16. The Tipping Point.

- ^ Clayton, Anthony (1 November 1992). Marsden, Gordon (ed.). "A Question of Honour? Scuttling Vichy's Fleet". History Today. 42 (11). London, England, United Kingdom: History Today Ltd: 32. ISSN 0018-2753.

- ^ Jackson, Peter; Kitson, Simon (2020) [2007]. "4. The paradoxes of Vichy foreign policy, 1940-1942". In Adelman, Jonathan R. (ed.). Hitler and his Allies in World War II (2 ed.). London, England, United Kingdom: Routledge. p. 82. doi:10.4324/9780203089552-4. ISBN 9780429603891. S2CID 216530750 – via Google Books.

- ^ Folly, Martin H. (2004). "The War in North Africa 1942". The Palgrave Concise Historical Atlas of the Second World War. Palgrave Concise Historical Atlases. New York City, New York, United States: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 45–46. doi:10.1057/9780230502390_23. ISBN 978-1-4039-0285-6.

- ^ a b Auphan & Mordal 2016, p. 114, Chapter 12. The Misunderstanding Over Article 8.

- ^ a b Mangold, Peter (2010). "Chapter 8. 'Ici Londres'". Britain and the Defeated French: From Occupation to Liberation, 1940-1944. London, England, United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 138. doi:10.5040/9780755625505.ch-008. ISBN 9781848854314 – via Google Books.

- ^ Grainger, John D. (2013). "Chapter 2 - The French Fleet". Traditional Enemies: Britain's War With Vichy France 1940-42. Barnsley, England, United Kingdom: Pen & Sword Books Ltd. p. 48. ISBN 9781783830794 – via Google Books.

- ^ Griffin, Stuart (2004). "6. Maritime power and complex crises: The Royal Navy and the undeclared war with Vichy France, 1940–1942". In Speller, Ian (ed.). The Royal Navy and Maritime Power in the Twentieth Century. Cass Series: Naval Policy and History (1 ed.). London, England, United Kingdom: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203002131. ISBN 9781134269822 – via Google Books.

- ^ Thomas, Martin (1 June 1997). Maddicott, JH; Stevenson, John (eds.). "After Mers-el-Kébir: The Armed Neutrality of the Vichy French Navy, 1940-43". The English Historical Review. 112 (447). Oxford, England, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press: 643–670. doi:10.1093/ehr/CXII.447.643. ISSN 0013-8266. JSTOR 576348. LCCN 05040370. OCLC 474766029. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ Symonds 2018, p. 77, 4. France Falls.

- ^ a b Upward 2016, p. 159, Chapter Three: From Victory to Defeat.

- ^ a b Korda, Michael (2007). "Chapter 11: Algiers". Ike: An American hero (1 ed.). New York City, New York, United States: HarperCollins. p. 325. ISBN 9780060756659. LCCN 2006052856. OCLC 148290264 – via Archive.org.

- ^ Gates, Eleanor M. (1981). "IV. The Question of the French Fleet". End of the Affair: The Collapse of the Anglo-French Alliance, 1939-40. Berkeley, California, United States: University of California Press. pp. 247–296. ISBN 9780520309333 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Deist, W.; et al. (1990). Germany and the Second World War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822884-8.

- ^ Upward 2016, p. 254, Chapter Five: Fighting for Germany, Fighting for France.

- ^ Plaquette concernant le 40eanniversaire de la libération de la Corse.

- ^ a b c Jordan, John; Dumas, Robert; et al. (Design by Stephen Dent, illustrations by Bertrand Magueur) (2009). "Chapter 3. Dunkerque and Strasbourg: 1932–1942". French Battleships 1922–1956. London, England, United Kingdom: Pen and Sword. pp. 92–99. ISBN 9781473828254 – via Google Books.

- ^ Jordan & Moulin, Chapter 10, The Fleet is Scuttled 27 November 1942

- ^ a b u-boote.fr HENRI POINCARÉ (in French) Accessed 3 September 2022

- ^ a b c Clayton, Anthony; et al. (Illustrations by Peter French) (2016) [2014]. "7. The Second World War 1943—1942". Three Republics One Navy: A Naval History of France 1870-1999. Solihull, England, United Kingdom: Hellion & Company Limited. pp. 102–136. ISBN 9781912174683 – via Google Books.

- ^ Mawdsley, Evan (2019). "Chapter 4. The Bitter Fate of the French Navy, 1940–44". The War for the Seas: A maritime history of World War II. New Haven, Connecticut, United States: Yale University Press. pp. 64–80. doi:10.12987/9780300248753-007. ISBN 9780300248753. LCCN 2019941052 – via Google Books.

- ^ Tessier, Erwan; Garnier, Cédric; Mullot, Jean-Ulrich; Lenoble, Véronique; Arnaud, Mireille; Raynaud, Michel; Mounier, Stéphane (1 October 2011). Sheppard, Charles; Richardson, B. (eds.). "Study of the spatial and historical distribution of sediment inorganic contamination in the Toulon bay (France)". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 62 (10). Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier: 2075–2086. Bibcode:2011MarPB..62.2075T. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.07.022. ISSN 0025-326X. PMID 21864863. S2CID 4840739. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ Simpson, Michael (1997). Duffy, Michael; Phil, D. (eds.). "Force H and British strategy in the Western Mediterranean 1939–42". The Mariner's Mirror. 83 (1). Glasgow, Scotland, United Kingdom: Society for Nautical Research/Taylor & Francis: 62–75. doi:10.1080/00253359.1997.10656629. ISSN 0025-3359. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ Thomas, R.T. (1979). "Britain and Vichy in 1942". Britain and Vichy: The Dilemma of Anglo-French Relations 1940–42. The Making of the 20th Century. London, England, United Kingdom: Palgrave. pp. 118–137. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-16052-5_7. ISBN 978-0-333-24312-1 – via Google Books.

- ^ Cunnhingham, Andrew Browne (2018) [2006]. "Part I: The British Admiralty Delegation, Washington, D.C., March to September 1942". In Simpson, Michael (ed.). The Cunningham Papers: Volume II: The Triumph of Allied Sea Power 1942–1946. Vol. 2. London, England, United Kingdom: Routledge. p. 23. ISBN 9781000340853 – via Google Books.

- ^ Rodogno, Davide (2008) [2003]. "6. Relations with the occupied territories". Fascism's European Empire: Italian Occupation During the Second World War. New Studies in European History. Translated by Adrian Belton (2 ed.). Cambridge, England, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 216. ISBN 9780521845151. OCLC 65203222.

- ^ O'Hara, Vincent P. (2012). "Italian Social Republic, Navy". In Tucker, Spencer C.; Pierpaoli Jr., Paul G.; Osborne, Eric W.; O'Hara, Vincent P. (eds.). World War II at Sea: An Encyclopedia. Vol. I. Santa Barbara, California, United States: ABC-CLIO. pp. 388–491. ISBN 9781598844573 – via Google Books.

- ^ Tucker-Jones, Anthony (2009). "Chapter Three: Churchill and Monty take on Ike". Operation Dragoon: The Liberation of Southern France, 1944. Barnsley, England, United Kingdom: Pen & Sword Books. p. 78. ISBN 9781844685325 – via Google Books.

- ^ Burton, Earl; Pincus, JH (1 September 2004). O'Leary, Michael (ed.). "The Other D-Day: The Invasion of Southern France". Sea Classics. 37 (9). Chatsworth, California, United States: Challenge Publications, Inc.: 60–70.

Bibliography

edit- Upward, Alexander John (2016). Blobaum, Robert; Aaslestad, Katherine (eds.). Ordinary Sailors: The French Navy, Vichy and the Second World War (PDF). Eberly College of Arts and Sciences (PhD). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. Morgantown, West Virginia, United States: West Virginia University. doi:10.33915/etd.6852 – via The Research Repository @ WVU.

- Auphan, Paul; Mordal, Jacques (15 July 2016) [1959]. The French Navy in World War II. Translated by A.C.J. Sabalot (2 ed.). Annapolis, Maryland, United States: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 9781682470602 – via Google Books.

- Symonds, Craig L. (2018). World War II at Sea: A Global History. New York City, New York, United States: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190243678. LCCN 2017032532 – via Google Books.

External links

edit- Media related to Scuttling of the French fleet at Toulon at Wikimedia Commons

- Works related to Adolf Hitler's Letter to Marshal Petain Announcing Decision to Occupy Toulon at Wikisource