The Secretum (Latin for 'hidden away') was a British Museum collection of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that held artefacts and images deemed sexually graphic. Many of the items were amulets, charms and votive offerings, often from pre-Christian traditions, including the worship of Priapus, a Greco-Roman god of fertility and male genitalia. Items from other cultures covered wide ranges of human history, including ancient Egypt, the classical era Greco-Roman world, the ancient Near East, medieval England, Japan and India.

| Secretum | |

|---|---|

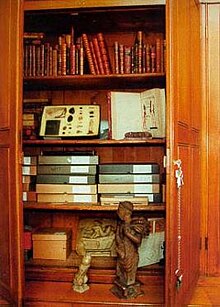

The Secretum in the latter part of the twentieth century, after its transfer to the Department of Medieval and Later Antiquities | |

| Housed at | British Museum |

| Size (no. of items) | c. 1,150 items |

| Funded by | |

Many of the early donations or sales to the museum, including those from the collectors Sir Hans Sloane, Sir William Hamilton, Richard Payne Knight and Charles Townley, contained items with erotic or sexually graphic images; these were separated out by museum staff and not put on public display. Modern scholars believe the segregation was probably motivated by a paternalistic stance from the museum to keep what they considered morally dangerous material away from all except scholars and members of the clergy. By the 1860s there were around 700 such items held by the museum. In 1865 the antiquarian George Witt donated his phallocentric collection of 434 artefacts to the museum, which led to the formal setting up of the Secretum to hold his collection and similar items.

The Secretum collection began to be gradually broken up in 1912, with the transfer of items into departments appropriate for their time frame and culture. The last entry into the Secretum was in 1953, when the British Museum Library found 18th-century condoms being used as bookmarks in a 1783 publication they held. The last remaining items were moved out of the collection in 2005.

Background

editThe British Museum Act created the British Museum in June 1753. The Act provided for the purchase of the collection of the physician and collector Sir Hans Sloane; the Cotton library, assembled by the antiquarian Sir Robert Cotton; and the Harleian Library, the collection of Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer. It was intended as a resource for "all studious and curious persons" and was the world's first free-access national museum.[1][2] Collectors of classical artefacts donated or sold their acquisitions to the museum, including major works, such as the Elgin Marbles in 1816.[3][4]

The library holdings of the British Museum—which were separated from the Museum to form the British Library in 1973—separated any obscene or pornographic publications in the nineteenth century. Although there is no agreed date when this began,[5] the informal practice of locking away such works was in place by at least 1836. The practice eventually became formalised as the Private Case; dates between 1841 and 1870 have been suggested for its inception.[6] The practice of separating works away from publicly accessible collections had an antecedent in the National Archaeological Museum, Naples—the museum whose collection includes Roman artefacts from the nearby Pompeii, Stabiae and Herculaneum sites—whose Secret Cabinet (Italian: Gabinetto Segreto) contained the erotic works found in those locations.[7]

History

editPre-Secretum, 1750s to 1865

editFrom the earliest days of the British Museum, its acquisitions included articles that displayed erotic or sexually graphic images. Among Sloane's donations, for example, were three lamps: one depicting a dancer showing his large phallus swinging behind him, according to the museum's catalogue;[8] one showing a woman and a monkey engaged in intercourse;[9] and one showing an ass having sex with a lion.[10] Subsequently acquired collections with sexually graphic images included that of Sir William Hamilton, who sold part of his collection to the museum in 1772 for £8,400, and later made further donations.[11][a] Hamilton's donation included votive wax phalluses from the Italian town Isernia.[13] The classical scholar and collector Richard Payne Knight's study of pre-Christian cultures included much on the subject of Priapus, a Greco-Roman god of fertility and male genitalia. In 1786 he published an examination of pagan beliefs and practices in A Discourse on the Worship of Priapus, and its Connection with the Mystic Theology of the Ancients.[b] He had collected widely in his studies, and when he died in 1824 his acquisitions were bequeathed to the British Museum. Comprising more than 1,140 drawings, 800 bronzes and in excess of 5,200 coins,[15][16] their value was estimated at either "at least £30,000"[15] or £50,000.[17][18][c] The antiquarian Charles Townley sold his classical sculpture collection to the museum in 1805, and the remainder was bequeathed to his cousin, Peregrine, who then sold it to the museum.[19] Townley's collection included an erotic frieze from an Indian tantra temple, a statue of Pan having sex with a goat and a statue of a nymph and satyr that depicts either sexual play or a possible attempted rape.[20][21]

The erotically charged or sexually graphic images from collections of Hamilton, Knight and Townley were from ancient Egypt, the Greco-Roman world and the ancient Near East. These items were separated from the rest of the donations and stored apart from the museum's public displays.[22][23] Further material with sexual imagery was deposited in the collection in the 1840s and 1850s.[22]

Official formation, 1865 onwards

editAlthough from its inception the British Museum had separated out the material considered obscene, the Secretum (Latin for "hidden away") was only formally founded in 1865. The Secretum came under the auspices of the museum's Department of British and Mediaeval Antiquities and Ethnography, headed by Augustus Wollaston Franks.[24] At that point it comprised about 700 items.[25][26] In 1865 George Witt, a collector of antiquities, suffered a bad illness; on his recovery, he wrote to Anthony Panizzi, the head of the British Museum, offering his phallocentric collection of 434 artefacts:

During my late severe illness it was a source of much regret to me that I had not made such a disposition of my Collection of "Symbols of the Early Worship of Mankind", as, combined with its due preservation, would have enabled me in some measure to have superintended its arrangement. In accordance with this feeling I now propose to present my collection to the British Museum, with the hope that some small room may be appointed for its reception in which may also be deposited and arranged the important specimens, already in the vaults of the Museum—and elsewhere, which are illustrative of the same subject.[27]

Witt's interest lay in phallicism and fertility in pre-Christian societies, particularly on the worship of Priapus.[28] Witt believed that all pre-Christian cultures possessed a common religious background which venerated fertility deities, according to the archaeologist and museum executive David Gaimster,[29] and Witt included with his donation a self-published pamphlet Catalogue of a Collection Illustrative of Phallic Worship.[30] Also included in Witt's acquisitions were artefacts from Greek, Egyptian and Roman antiquity, reliefs from Indian temples, medieval items and nine bound scrapbooks containing prints and watercolours of fertility-related objects from cultures around the world.[29][31] The archaeologist Helen Wickstead describes the scrapbooks as being "among the world's most valuable resources for investigating the history of archaeologies of sexuality".[32] Many of the items in the Witt collection were good-luck amulets, often shaped as or displaying winged phalluses.[33] He also donated works of shunga—Japanese erotic art—the first of that style held by the museum[34] and what he thought was a medieval chastity belt, although this was a fake manufactured in Victorian times.[35] In 2000 the journalist Laura Thomas observed that Witt "did not care to place ... [his collection] in any cultural or chronological milieu. Regardless of provenance ... [he] selected the pieces for their obscenity value alone".[36] According to Gaimster, the Secretum "took on its official status" with Witt's donation.[37]

The British Museum did not promote its ownership of the Secretum and access to it was restricted to clergymen and scholars;[39] they would have to apply by letter to the director of the museum giving details of their credentials and a valid reason why they wanted to access the collection.[40] One application—made in 1948—was from a scholar who requested a copy of the collection's register; he was asked to explain "his qualifications for the study of the catalogue, the use he proposed to make of the photostats, and the arrangements made for the disposal thereof at his death".[25]

The classicist Jen Grove considers that rather than being embarrassed by its ownership of salacious and pornographic material, the British Museum actively and systematically sought out sexual antiquities, either to add to the Secretum or into their main holdings. This enthusiastic acquisition continued from the nineteenth into the twentieth century, including the period from 1912 when the Secretum collection was being broken up and transferred to other departments within the museum. Grove notes that while some of the acquired items were entered into the Secretum, many were not, but instead went into the museum department appropriate for their time frame and culture.[41]

Break-up, 1912 to 2000s

editObjects began to be released from the Secretum early in the twentieth century, with some artefacts transferred to the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities in 1912.[42][43] There was further transfer of items out of the collection from 1937 onwards,[42][44] although the museum continued to add to the collection. The last entry into the Secretum was in 1953, when the British Library passed to the museum some 18th-century condoms that had been used as bookmarks in the 1783 publication A Guide to Health, Beauty, Riches and Honour. The condoms were made of sheep intestines, with drawstrings at the open end to seal and secure them.[25][45] After 1953 any new items acquired by the museum with erotic content were stored within or displayed by the department relevant for their time frame and culture.[40]

During the 1960s the curatorship of the Secretum was moved to the newly formed Department of Medieval and Later Antiquities, where they were housed in locked cupboards 55 and 54 of the museum;[46] "Cupboard 55" became one of the nicknames by which the Secretum was known.[47] The collection was gradually reduced over time by transferring items to the relevant department and in 2000 it contained around 200 of Witt's donations and 100 items from pre-1865 donations.[25] In 2002 one of the collection's curators said "what's left in the Secretum now is fairly pathetic. It's kept here because it's second rate and not worthy of display anywhere else".[48] By 2005 the last remaining items had been redistributed,[49] although there were still some erotic prints and cartoons locked in cupboard 205 of the Department of Prints and Drawings in 2009.[50]

From the 1970s onwards, when Roman vases depicting ithyphalli (from the Latin for "erect penises") were placed in the main displays, the British Museum chose to display sexually explicit objects integrated into its main displays, in contrast with the Neapolitan National Archaeological Museum, which segregated them into a single room with warning signs on entry.[51][44]

Rationale and academic discipline

editRationale

editSome classicists and curators—including Gaimster and the archaeologist and museum curator Catherine Johns—have written that what Johns calls "Victorian prudery" was behind the decision to segregate the sexually graphic items from the main collection.[52][30][53] Gaimster observes that such a classification was, therefore, not on an academic basis, but a moral one;[7] Johns considers that classifying artefacts on grounds of obscenity is "academically indefensible" and that there is no scholarly basis to label any object as obscene.[54]

The art curator Marina Wallace also considers that a paternalistic approach was behind the decision, and that the censorship of items was made by educated men, who thought themselves able to study artefacts that displayed erotic or sexually graphic images without offence or the danger of moral corruption, whereas the images would "offend the weaker members of society, that is to say, children, women and the working classes".[53]

Gaimster notes that the Secretum was formally started soon after the introduction of the Obscene Publications Act 1857.[7] The legislation made no allowances for the educational nature of the material, and in 1860 an anatomical museum in Leeds was prosecuted under the act and the anatomical models were destroyed on the grounds they were "dangerous to public morality".[55] Gaimster considers the Secretum's formation was possibly as a result of the new legislation.[7]

Academic discipline

editThe art historian Peter Webb considers that the Secretum was "one of the finest collections of erotica in the world".[56] The Egyptologist Richard Parkinson writes that the Secretum was among the first steps in the scientific "study [of] human sexuality across cultures". It was this growing discipline of the late nineteenth century that provided the backdrop to the studies by the physician and sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld.[57]

The historian Victoria Donnellan considers the collection "represents an interesting case study for the shifting lines of acceptability versus perceived obscenity".[58] Gaimster considers it useful as an example of Victorian collecting culture; in 2000 he wrote that the collection was "a product of its time, place and culture. It is a historical artefact in its own right, but also serves as a warning to future generations of historians against imposing their own contemporary prejudices on the material culture of the past."[25] Johns says the individual items should be studied in the context of their own time: "When you take these objects out of time and lump them together you relate them not to the culture which produced them but to the culture of Victorian England".[45]

Notes and references

editNotes

edit- ^ £8,400 in 1772 equates to approximately £1,356,000 in 2023, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[12]

- ^ When Knight's work on Priapus was published, Edward Hawkins, the Keeper of Antiquities at the British Museum, wrote "Of this work it is impossible to speak in terms of reprobation sufficiently strong: it is a work too gross to mention: and it is quite impossible to quote the indignant but too descriptive language of the critics in their severe but just remarks upon this disgusting production".[14]

- ^ £30,000 in 1814 equates to approximately £2,651,000 in 2023; £50,000 in 1814 equates to approximately £4,418,000 the same year, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[12]

References

edit- ^ Miller 1974, p. 46; Cuno 2011, p. 13.

- ^ "History of the British Museum". The British Museum.

- ^ Burnett & Reeve 2001, p. 12.

- ^ "Collecting Histories". The British Museum.

- ^ Cross 1991, p. 203.

- ^ Cross 1991, pp. 203–204; Fryer 1966, p. 41; Legman 1981, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d Gaimster 2000, p. 10.

- ^ "Lamp (object 1756,0101.1088)". The British Museum.

- ^ "Lamp (object 1756,0101.648)". The British Museum.

- ^ "Lamp (object 1756,0101.270)". The British Museum.

- ^ "Sir William Hamilton". The British Museum.

- ^ a b Clark 2023.

- ^ Gaimster 2001, p. 130.

- ^ Johns 1982, p. 25.

- ^ a b Stumpf-Condry & Skedd 2015.

- ^ "Richard Payne Knight". The British Museum.

- ^ Wright 1865, p. i.

- ^ Johns 1982, p. 24.

- ^ "Charles Townley". The British Museum.

- ^ Donnellan 2019, pp. 149, 158, 160.

- ^ "Tantra at the British Museum". British Museum.

- ^ a b Frost 2010, p. 140.

- ^ Johns 1982, p. 29.

- ^ Gaimster 2000, pp. 10, 12; Grove 2013, p. 55; Olson 2014, p. 168; Caygill 1997, pp. 71–72.

- ^ a b c d e Gaimster 2000, p. 15.

- ^ Grove 2013, p. 17.

- ^ Gaimster 2000, p. 13.

- ^ Johns 1982, p. 28; Gaimster 2022; Frost 2008, p. 31.

- ^ a b Gaimster 2001, p. 132.

- ^ a b Gaimster 2000, p. 14.

- ^ Wallace 2007, p. 35.

- ^ Wickstead 2018, p. 351.

- ^ Thomas 2000, p. 162.

- ^ Frost 2017, p. 86.

- ^ Thomas 2000, p. 163.

- ^ Thomas 2000, p. 164.

- ^ Gaimster 2000, pp. 12–13.

- ^ "Cup (object 1867,0508.1064)". The British Museum.

- ^ Frost 2017, p. 88; Grove 2013, p. 17; Smith 2007, p. 139.

- ^ a b Frost 2008, p. 31.

- ^ Grove 2013, p. 58.

- ^ a b Donnellan 2019, p. 163.

- ^ Grove 2013, p. 62.

- ^ a b Frost 2010, p. 141.

- ^ a b Rogers 1999.

- ^ Gaimster 2000, p. 12.

- ^ Thomas 2000, p. 161.

- ^ Morrison 2002, p. 16.

- ^ Perrottet 2011, p. 6.

- ^ Barrell 2009.

- ^ Smith 2007, p. 139.

- ^ Johns 1982, p. 32.

- ^ a b Wallace 2007, p. 38.

- ^ Johns 1982, p. 30.

- ^ Bates 2008, p. 14.

- ^ Webb 1998, p. 487.

- ^ Parkinson 2013, p. 87.

- ^ Donnellan 2019, p. 158.

Sources

editBooks

edit- Burnett, Andrew; Reeve, John (2001). Behind the Scenes at the British Museum. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-2196-3.

- Caygill, Marjorie (1997). "Franks and the British Museum—the Cuckoo in the Nest". A. W. Franks: Nineteenth-Century Collecting and the British Museum. London: British Museum Press. pp. 51–114. ISBN 978-0-7141-1763-8.

- Cross, Paul (1991). "The Private Case: A History". In Harris, P. R. (ed.). The Library of the British Museum: Retrospective Essays on the Department of Printed Books. London: The British Library. pp. 201–240. ISBN 978-0-7123-0242-5.

- Cuno, James B. (2011). Museums Matter: In Praise of the EncyclopedicMuseum. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-12677-7.

- Donnellan, Victoria (2019). "Ethics and Erotics: Receptions of an Ancient Statue of a Nymph and Satyr". In Funke, Jana; Grove, Jen (eds.). Sculpture, Sexuality and History: Encounters in Literature, Culture and the Arts from the Eighteenth Century to the Present. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 145–170. ISBN 978-3-3199-5839-2.

- Frost, Stuart (2010). "The Warren Cup: Secret Museums, Sexuality and Society". In Levin, Amy K. (ed.). Gender, Sexuality and Museums: A Routledge Reader. London: Routledge. pp. 138–150. ISBN 978-0-415-55491-6.

- Fryer, Peter (1966). Private Case—Public Scandal: Secrets of the British Museum Revealed. London: Secker and Warburg. OCLC 314927730.

- Gaimster, David (2001). "Under Lock and Key". In Bayley, Stephen (ed.). Sex. London: Cassell. pp. 127–139. ISBN 978-0-304-35946-2.

- Johns, Catherine (1982). Sex or Symbol: Erotic Images of Greece and Rome. London: British Museum. ISBN 978-0-7141-8042-7.

- Legman, Gershon (1981). Introduction. The Private Case: An Annotated Bibliography of the Private Case Erotica Collection in the British (Museum) Library. By Kearney, Patrick. London: Jay Landesman. pp. 11–59. ISBN 978-0-9051-5024-6.

- Miller, Edward (1974). That Noble Cabinet: A History of the British Museum. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-0139-2.

- Olson, Kelly (2014). "Roman Sexuality and Gender". In Gibbs, Matt; Nikolic, Milorad; Ripat, Pauline (eds.). Themes in Roman Society and Culture: An Introduction to Ancient Rome. Ontario: Oxford University Press. pp. 164–188. ISBN 978-0-1954-4519-0.

- Parkinson, R. B. (2013). A Little Gay History: Desire and Diversity Across the World. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-2311-6663-8.

- Perrottet, Tony (2011). The Sinner's Grand Tour: A Journey Through the Historic Underbelly of Europe. New York: Broadway Books. ISBN 978-0-307-59218-7.

- Smith, Rupert (2007). The Museum: Behind the Scenes at the British Museum. London: BBC Books. ISBN 978-0-563-53913-1.

- Wallace, Marina (2007). Seduced: Art and Sex from Antiquity to Now. London: Barbican. ISBN 978-1-8589-4416-6.

- Webb, Peter (1998). "Erotic Art". In Turner, Jane (ed.). The Dictionary of Art. New York: Grove. pp. 472–487. ISBN 978-1-884446-00-9.

- Wright, Thomas (1865). Preface. A Discourse on the Worship of Priapus, and its Connection with the Mystic Theology of the Ancients. By Knight, Richard Payne; Wright, Thomas. London: Privately printed. pp. i–iii. OCLC 1404206315.

Journals and magazines

edit- Bates, A. W. (1 January 2008). "'Indecent and Demoralising Representations': Public Anatomy Museums in mid-Victorian England" (PDF). Medical History. 52 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1017/S0025727300002039.

- Frost, Stuart (April 2008). "Secret Museums: Hidden Histories of Sex and Sexuality". Museums & Social Issues. 3 (1): 29–40. doi:10.1179/msi.2008.3.1.29.

- Gaimster, David (September 2000). "Sex and Sensibility at the British Museum". History Today. Vol. 50, no. 9. pp. 10–15.

- Thomas, Laura (May 2000). "Eye of the Beholder". Index on Censorship. 29 (3): 161–165. doi:10.1080/03064220008536740.

- Wickstead, Helen (2 September 2018). "Sex in the Secret Museum: Photographs from the British Museum's Witt Scrapbooks" (PDF). Photography and Culture. 11 (3): 351–366. doi:10.1080/17514517.2018.1545887. ISSN 1751-4517.

Websites

edit- "Charles Townley". The British Museum. Archived from the original on 10 October 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- Clark, Gregory (2023). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- "Collecting Histories". The British Museum. Archived from the original on 15 March 2023. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- "Cup (object 1867,0508.1064)". The British Museum. Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- Gaimster, David (2022). "Witt, George (1804–1869)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/74100. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "History of the British Museum". The British Museum. Archived from the original on 15 March 2023. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- "Lamp (object 1756,0101.270)". The British Museum. Archived from the original on 27 May 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- "Lamp (object 1756,0101.648)". The British Museum. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- "Lamp (object 1756,0101.1088)". The British Museum. Archived from the original on 26 February 2024. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- "Richard Payne Knight". The British Museum. Archived from the original on 19 January 2024. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- "Sir William Hamilton". The British Museum. Archived from the original on 9 November 2023. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- Stumpf-Condry, C.; Skedd, S. J. (2015). "Knight, Richard Payne (1751–1824)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/15733. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Tantra at the British Museum". British Museum. Archived from the original on 21 December 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

Newspapers

edit- Barrell, Tony (30 August 2009). "Rude Britannia: Erotic Secrets of the British Museum". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011.

- Morrison, Richard (30 August 2002). "A Rude Awakening". The Times. pp. 16–17.

- Rogers, Byron (19 June 1999). "The Secrets of Cupboard 55". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

Theses and papers

edit- Frost, Stuart (2017). Lehnes, Patrick; Frost, Stuart (eds.). Secret Museums and Shunga: Sex and Sensitivities. Proceedings of the Interpret Europe Conferences in Primošten and Kraków (2014 and 2015).

- Grove, Jennifer (May 2013). The Collection and Reception of Sexual Antiquities in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century (PDF) (PhD thesis). Exeter University. OCLC 890158966. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2024. Retrieved 15 February 2024.