The prehistoric and ancient history of the Serer people of modern-day Senegambia has been extensively studied and documented over the years. Much of it comes from archaeological discoveries and Serer tradition rooted in the Serer religion.[2][3]

Ancient history

editIn Charles Becker's paper titled "Vestiges historiques, trémoins matériels du passé clans les pays Sereer", two types of Serer relics were noted: "the non-material remains which are cultural in nature" and "material remains, which are many revealed through products or artefacts."[2] The historical vestiges of Serer country in modern-day Senegambia, the diversity of Serer culture manifested across dialects, family and social organisation which reflect different historical territories were observed.

Although many Serer artefacts remain unknown, unlisted and preserved despite the efforts in the 1960s and 1970s to collect, archive and document them all, many material relics were found in different Serer countries, most of which refer to the past origins of Serer families, villages and Serer Kingdoms. Some of these Serer relics included gold, silver and metals.[2][4] The known objects found in Serer countries, are divided into two types:

1. the remnants of earlier populations.

- " These are the traces left by the proto-populations with which the Sereer were in contact when they came from the Fuuta".[2]

2. Laterite megaliths carved planted in circular structures with stones directed towards the east are found only in small parts of the ancient Serer kingdom of Saloum.

- The sand tumulus, on the other hand which resembles ancestral tombs ("lomb" in Serer language) still built by Serers are observed everywhere including the Kingdom of Sine, Jegem (Njegem), Kingdom of Saloum.[2][5]

Archaeological sites

editMegalithic zone: Many megalithic sites include mounts in the ancient Kingdom of Saloum, with a frequent association of mound of sand with megalithic stones – front to East.[6]

Shell mounds are also found in the islands and around the estuary of Saloum. In the provinces of the Gandun, Numi, Saloum and south-western Sine around Joal, 139 sites have been identified and they sometimes have shaped burial mounds.[2][7] These relics are very numerous and imposing.[6] The graves of the founding ancestors were also very often sanctified as "Fangool" (singular of Pangool: "ancestral spirit" or "saint" in Serer religion). Such relics associated with the ancestors are often venerated relics.[2] For example, the relics evoking memories of migration or foundation of states are sometimes sacralised. The remnants of royalty in the Kingdoms of Sine and Saloum are similar because the "Geulowars" (the last maternal dynasty in Sine and Saloum - 14th to 20th century[8]) have the same Serer tradition, but there are peculiarities in the objects and the scene of the coronation of royalty and power which have existed since the beginnings of dynasty with the annual ritual and mandatory ceremonies.[2] The family relics in other Serer countries which are brought from Takrur (now Futa Toro) or Kaabu by the founders were also noted in places of worship of the village or province history. This may be stone, wood, musical instruments, ceremonial objects used by the Saltigue (Serer High Priests and Priestesses) or "Yaal Pangool".[2] These relics kept by families since ancient times remain largely unknown.[2]

There are two types of Serer relics relating to two lineages that come into play in the social organisation of the Serer people:

- "kucarla" - which means paternal lineage or paternal inheritance.

- "ƭeen yaay" - which means maternal lineage or maternal inheritance.[6]

The history of the Serer people who resided at Takrur (now Futa Toro) which was part of what is generally referred to as Serer country,[9] the influence of their culture, history, religion and tradition on the land is summarized by Becker in the following terms :

Finally we should remember the important relic call Sereer in Fouta, but also in the former countries of the Ferlo, Jolof and Kajoor, which marked the migration of proto-Sereer, whose imprint on the Fouta was so significant and remains in the memory of the Halpulaareen [speakers of the Pulaar language in Senegal and the Gambia such as Fula people and Toucouleur people].[2]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ a b c Gravrand, Henry: "La Civilisation Sereer – Pangool". Published by Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines du Senegal. 1990. pp, 9, 20 & 77. ISBN 2-7236-1055-1.

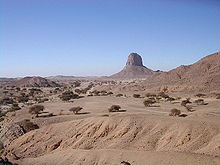

- From top to bottom: The first image is of the Senegambian stone circles (megaliths) which runs from Senegal all the way to The Gambia and described by UNESCO as "the largest concentration of stone circles seen anywhere in the world." It is believed that the site itself was an ancient burial ground. The second image is in (modern-day Mauritania) see West Saharan montane xeric woodlands. The third image is rock art in modern-day Mauritania. For all image references including the Tasili, see: Henry Gravrand. La Civilisation Sereer – Pangool. Published by Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines du Senegal. 1990. pp, 9, 20 & 77. ISBN 2-7236-1055-1

- Becker, Charles: "Vestiges historiques, trémoins matériels du passé clans les pays sereer". Dakar. 1993. CNRS – ORS TO M

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Vestiges historiques, trémoins matériels du passé clans les pays Sereer". Dakar. 1993. CNRS – ORS TO M

- ^ Henry Gravrand. La Civilisation Sereer – Pangool. Published by Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines du Senegal. 1990. p-p, 9, 20 & 77. ISBN 2-7236-1055-1

- ^ Charles Becker et Victor Martin, Rites de sépultures préislamiques au Sénégal et vestiges protohistoriques, Archives Suisses d'Anthropologie Générale, Imprimerie du Journal de Genève, Genève, 1982, tome 46, N° 2, p. 261-293

- ^ Cyr Descamps, Guy Thilmans et Y. ThommeretLes tumulus coquilliers des îles du Saloum (Sénégal), Bulletin ASEQUA, Dakar, Université Cheikh Anta Diop, Dakar, 1979, n° 54, p. 81-91

- ^ a b c "Vestiges historiques, trémoins matériels du passé clans les pays sereer". Dakar. 1993. Charles BECKER, CNRS – ORS TO M

- ^ Cyr Descamps, Guy Thilmans et Y. Thommeret. Les tumulus coquilliers des îles du Saloum (Sénégal), Bulletin ASEQUA, Dakar, Université Cheikh Anta Diop, Dakar, 1979, n° 54, p. 81-91

- ^ Alioune Sarr. Histoire du Sine-Saloum. Introduction, bibliographie et Notes par Charles Becker, BIFAN, Tome 46, Serie B, n° 3-4, 1986-1987

- ^ (in French) Chavane, Bruno A., "Villages de l’ancien Tekrour", Vol. 2, Hommes et sociétés. Archéologies africaines,p 10, KARTHALA Editions, 1985 ISBN 2-86537-143-3