The siege of Várpalota[a][b] was a military siege undertaken by the Ottoman Empire in October 1593 against the city of Várpalota, situated on the Military Frontier and under Habsburg rule. The Ottoman forces were led by Koca Sinan Pasha whilst the Habsburg garrison was commanded by Péter Ormándy. The siege was the second major engagement of the Long Turkish War, and resulted in the Ottomans capturing the city after two days.[2]

| Siege of Várpalota (1593) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Long Turkish War | |||||||||

Siege of Várpalota; Siege of Veszprém in the top left (1593) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Tens of thousands | 200 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Unknown | 194 killed | ||||||||

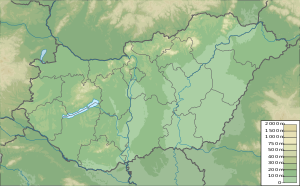

Location within Europe | |||||||||

Background

editAfter a prolonged war against Safavid Iran from which the Ottomans emerged victorious, they turned their eyes to Central Europe. Skirmishes across the Military Frontier between the Ottoman and Holy Roman empires was commonplace; akinjis and uskoks were the main culprits.[3] Emperor Rudolf II was also failing to pay 30,000 Hungarian ducats as annual tributes to Sultan Murad III, one of the provisions of the 1568 Treaty of Adrianople.[4] These combined factors greatly strained relations, and with the culmination of the Battle of Sisak, the Ottomans responded by waging war against the Habsburg monarchy on 29 July 1593. Thus, the Ottoman Empire was dragged into another decades-long conflict which was to be known as the Long Turkish War.[5]

Prelude

editBy October 1593, Koca Sinan Pasha amassed a force numbering tens of thousands.[6] The pasha marched to the Military Frontier alongside his son, Mehmed Pasha, Beylerbey of Greece. After reaching İstolni Belgrad (under Ottoman control since 1543),[7] he moved onto Veszprém which he captured within a few days. Remaining two days in the city, he advanced towards Várpalota with his son.[8]

Siege

editHaving reached the city, Sinan Pasha offered Péter Ormándy, the commander of the 200-strong garrison, to surrender. Ormándy, who had been the commander of the city since 1584, declined. This prompted the pasha to bring forth the cannons and fire at the city, while also threatening Ormándy that he would forcibly pit hundreds of Christian captives, including the commander and mayor of Veszprém (György Hofkirchen and Ferdinánd Samarjay, respectively) against him if he insisted in defending the city. With the bastions of the city severely damaged and to avoid battling with his Christian brethren, Ormándy negotiated a surrender after two days.[9] Although the pasha agreed to the terms of the surrendering (allowing the defenders to leave unscathed), when Ottoman troops entered the city they killed all the defenders other than six people (Péter Ormándy, the captain of the castle; Ormándy’s deputy, and four other castellans).[10]

Aftermath

editPéter Ormándy escaped to Győr, where he was imprisoned for surrendering Várpalota without much resistance. Nothing is known of his fate.[10]

Sinan Pasha, on the other hand, remained in Várpalota for a few days and suggested dividing his forces into two for wintering; one force stationed between Buda and Pest, the other at Segedin. However, the Janissaries objected to this proposal, in which case the pasha decided to head to Belgrad (which was safe from the Habsburgs) for wintering. In early November, Sinan Pasha allowed Ottoman vassal Prince Sigismund Báthory to dismiss his forces at Varad with the precondition of raising 60,000 men in Transylvania by spring of 1594 to aid Sultan Murad III’s upcoming campaign against the Habsburg monarchy.[10]

Notes

editCitations

edit- ^ İnalcık, Halil (2013). The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age, 1300-1600. Paris: Hachette UK. p. 139. ISBN 9781780226996.

- ^ Cartledge, Bryan (2011). The Will to Survive: A History of Hungary. New York City: Columbia University Press. p. 100. ISBN 9780231702249.

- ^ Shaw, Stanford J.; Shaw, Ezel K. (1976). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 184. ISBN 9780521291637.

- ^ Setton, Kenneth M. (1984). The Papacy and the Levant (1204–1571), Volume IV: The Sixteenth Century from Julius III to Pius V. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. p. 921. ISBN 0-87169-162-0.

- ^ Imber, Colin (2002). The Ottoman Empire, 1300-1650: The Structure of Power. New York City: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 67. ISBN 9780333613863.

- ^ Pálffy, Géza (2021). Hungary Between Two Empires 1526–1711. Translated by David R. Evans. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 115. doi:10.2307/j.ctv21hrjwj. ISBN 9780253054678.

- ^ Hegyi, Klára [in Hungarian] (2019). "Ottoman Defence System in Hungary". In Fodor, Pál (ed.). The Battle for Central Europe. Leiden: Brill. pp. 309–319. doi:10.1163/9789004396234_016.

- ^ Horváth, Jenő (1897). Magyar Hadi Krónika: A Magyar Nemzet Ezeréves Küzdelmeinek Katonai Története [Hungarian War Chronicle: The Military History of the Thousand-Year Struggles of the Hungarian Nation] (PDF) (in Hungarian). Vol. 2. Budapest: Hungarian Academy of Sciences. p. 113.

- ^ Ágoston, Gábor (2021). The Last Muslim Conquest: The Ottoman Empire and Its Wars in Europe. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 251. ISBN 9780691159324.

- ^ a b c Bánlaky, József [in Hungarian]. "A Magyar Nemzet Hadtörténelme" [The Military History of the Hungarian Nation]. arcanum.com (in Hungarian).