Somatocentrism is a cultural value system in which biological determinism is the basis for social organization. The phenotypical variation of an individual in this system determines the individual's social identity and social relations, although it does not necessarily denote their social position.

Definition

editThe term ‘somatocentric’ is derived from

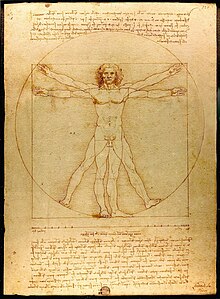

In this system, the physical body of an individual is heavily emphasized, and valued in determining the social identity of the individual.

Perception

editA necessary precondition for individuals in a somatocentric system is the privileging of sight over other senses in perceiving reality. Using vision as the primary sense for constructing reality may cause one to miss complex and hidden nuances of existence, limiting perception.[1] A comparison of sight and hearing shows that sight is mono-directional and exclusive, while sound is proximate, fluid, and inclusive.[2]

Privileging sight over other senses facilitates a type of self-image that focus on the individual's body, as vision is the primary means to delineate phenotypical difference. Identifying these differences this way may lead to attributing social value to individuals who look a certain way.

Body Image

editBody image is a subjective picture of one's own physical appearance established both by self-awareness and by noting the reactions of others.[3] Preoccupation with body image and the physical appearance of one's body denotes how much value one ascribes to their phenotypical traits. Body image may be valued highly, and more often than not, dissatisfaction with one's own body image perverts that value with other social effects.

Body Dysmorphic Disorder

editPeople who suffer from Body Dysmorphic Disorder (or BDD) fixate on a defect in their appearance. People with BDD are affected daily with stress and anxiety, which may impair their role in the social and occupational areas of their life. The amount of social value ascribed to the importance of body image affects the level of stress someone suffering from BDD feels.[4]

Height

editStudies show that in some cultures, people who are relatively taller than others get relatively better treatment by their peers.

A study conducted in Australia found that tall people earn higher wages than their equally competent shorter co-workers.[5] A study conducted in Southampton of ninety-two normal teens who were shorter than their peers revealed that the shorter boys were twice as likely to be bullied than their average height controls matched by sex and age.[6] The findings of these studies reveal a correlation between height and social value, indicating somatocentric issues.

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists define ‘short stature’ as being two standard deviations below the average for a particular age and sex; in America, a male shorter than 5’7’’ and a female shorter than 5’2’’ are both short statured.[7] Groups have been formed by people who feel short, such as The National Organization of Short Statured Adults (NOSSA). One of the primary functions of this group is to inform its members of the sociological and psychological aspects of being short statured as research continues.[8]

Racism

editRacism is defined by a belief that race is the primary determinant of human traits and capacities and that racial differences produce an inherent superiority of a particular race.[9] Racial differences are most easily compared by the phenotypical differences between peoples of a different race, i.e. skin tone, facial features, hair color, and body type. To place social value on any trait, whether positive or negative, is a product of somatocentric values.

Gender

editA somatocentric culture may create social constructs based on the interpretation of biological differences between its individuals. The concept of ‘gender’ is an example of a construct that may arise from somatocentricity. Sex and gender are loosely related as they both deal with the male and the female; however, one considers empirical distinction, while the other considers social distinction.[10]

A sex refers to biological distinctions between males and females. Certain biological structures are unique to either females or males; in humans, the ovary being unique to the former, the prostate gland being unique to the latter. Biological differences between males and females govern the action of reproduction in any species that repopulates via sexual reproduction, and in some cases, influence the action of child-rearing.

By contrast, gender roles, gender identities, and the concepts of masculine and feminine are all social constructs which may be extrapolated from phenotypical differences between men and women.[10]

For example, in Western culture, women may fill domestic social roles, with an emphasis on childcare. Women are also unique members of a population that are outfitted with breasts which help feed infants, while men lack these organs. While it is logical to assert that women may be biologically better suited for postnatal care of an infant than men, it does not follow from the ability to breast-feed that women are better suited to domestic social roles than men.

Masculinity and Femininity

editMasculinity and femininity are also engendered concepts that may draw from phenotypical difference between male and female. A person who exhibits physical strength may be deemed masculine, while a person who exhibits gentleness may be deemed feminine. Attributing significance to the phenotypical difference between the size or shape of men and women creates a binary between the two that allows the casual observer to presume social significance of a person in terms of this arbitrary scale.[10]

External links

edit- Merriam-Webster Online. Merriam-Webster, Inc. Web. 25 September 2011. Merriam-Webster Dictionary

- Fox, Kate. Body Image Studies. Social Issues Research Centre. 1997. Web. 25 September 2011. [6]

- Voss, Linda D. and Mulligan, Jean. Bullying in school: are short pupils at risk? British Medical Journal, 1 November 2000. Web. 25 September 2011. [7]

- NOSSA, National Organization of Short Statured Adults, Inc. [8]

References

edit- ^ Coetzee, Pieter Hendrik, Race and Gender, 28 September 2001.

- ^ Lowe, David: History of Bourgeois Perception. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982, pp. 7

- ^ Merriam-Webster Online, Body image, "[1]", 25 September 2011.

- ^ Fox, Kate. Body Image Studies, 1997. "[2]", 25 September 2011.

- ^ Alexander, Kathy. Tall men earn $1000 more than short ones, 17 May 2009. "[3]", 25 September 2011.

- ^ Voss, Linda D. and Mulligan, Jean. Bullying in school: are short pupils at risk?, 1 November 2000. "[4]", 25 September 2011.

- ^ "NOSSA, What is short statured?", 2011, ""NOSSA, National Organization of Short Statured Adults". Archived from the original on 2011-09-26. Retrieved 2011-09-25.", 25 September 2011.

- ^ "NOSSA, About Us", 2011, ""NOSSA, National Organization of Short Statured Adults". Archived from the original on 2011-10-04. Retrieved 2011-09-25.", 25 September 2011.

- ^ Merriam-Webster Online, Racism, "[5]", 25 September 2011.

- ^ a b c Oyewumi, Oyeronke, The Invention of Women, 1997, 5 September 2011