Song Offerings (Bengali: গীতাঞ্জলি) is a volume of lyrics by Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore, rendered into English by the poet himself, for which he was awarded the 1913 Nobel Prize in Literature.[1]

Gitanjali title page (with an introduction by W. B. Yeats) | |

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Original title | গীতাঞ্জলি |

| Translator | Rabindranath Tagore |

| Language | Bengali |

| Subject | Devotion to God |

| Genre | Poem |

| Publisher | India Society, Macmillan and Company |

Publication date | 1912 |

| Publication place | British India |

| Pages | 104 |

| Text | Gitanjali (Song Offerings) at Wikisource |

Contents

editSong Offerings is often identified as the English rendering of Gitanjali (Bengali: গীতাঞ্জলি), a volume of poetry by poet Rabindranath Tagore composed between 1904 and 1910 and published in 1910. However, in fact, Song Offerings anthologizes also English translation of poems from his drama Achalayatan and nine other previously published volumes of Tagore poetry.[2] The ten works, and the number of poems selected from each, are as follows:[3]

- Gitanjali - 69 poems (out of 157 poems in Song Offerings)

- Geetmalya - 17 poems

- Naibadya - 16 poems

- Kheya - 11 poems

- Shishu - 3 poems

- Chaitali - 1 poem

- Smaran - 1 poem

- Kalpana - 1 poem

- Utsarga - 1 poem

- Acholayatan - 1 poem

Song Offerings is a collection of devotional songs to the supreme. The deep-rooted spiritual essence of the volume is brought out from the following extract :

My debts are large,

my failures great,

my shame secret and heavy;

yet I come to ask for my good,

I quake in fear lest my prayer be granted.

(Poem 28, Song Offering)

The word gitanjali is composed from "geet", song, and "anjali", offering, and thus means – "An offering of songs"; but the word for offering, anjali, has a strong devotional connotation, so the title may also be interpreted as "prayer offering of song".[4]

Nature of translation

editRabindranath Tagore took the liberty of doing "free translation" while rendering these 103 poems into English. Consequently, in many cases these are transcreations rather than translation; however, literary biographer Edward Thomson found them 'perfect' and 'enjoyable'. A reader can himself realize the approach taken by Rabindranath in translating his own poem with that translated by a professional translator. First is quoted lyric no. 1 of Song Offering as translated by Rabindranath himself :

Thou hast made me endless, such is thy pleasure.

This frail vessel thou emptiest again and again,

and fillest it ever with fresh life.

This little flute of a reed thou hast carried over hills and dales, and hast breathed through it melodies eternally new.

At the immortal touch of thy hands

my little heart loses its limits in joy and gives birth to utterance ineffable.

Thy infinite gifts come to me only on these very small hands of mine.

Ages pass, and still thou pourest, and still there is room to fill.

It is the Lyric number 1 of Gitanjali. There is another English rendering of the same poem by Joe Winter translated in 1997:[5]

Tagore undertook the translations prior to a visit to England in 1912, where the poems were extremely well received. In 1913, Tagore became the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, largely for the English Gitanjali.[6]

Publications

editThe first edition of Song Offerings was published in 1912 from London by the India Society. It was priced ten and a half shillings. The second edition was published by The Macmillan Company in 1913 and was priced at four and a half shillings.

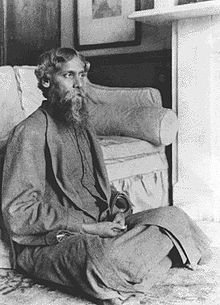

The second edition contained a sketch of the poet by Rothenstein (see the image on right), in addition to an invaluable preface by W. B. Yeats.[7]

Introduction by Yeats

editAn introduction by poet W. B. Yeats was added to the second edition of Song Offerings. Yeats wrote that this volume had "stirred my blood as nothing has for years. . . ." He candidly informed the readers, "I have carried the manuscript of these translations about with me for days, reading it in railway trains, or on the top of omnibuses and in restaurants, and I have often had to close it lest some stranger would see how much it moved me. These lyrics--which are in the original, my Indians tell me, full of subtlety of rhythm, of untranslatable delicacies of colour, of metrical invention—display in their thought a world I have dreamed of all my live long." Then, after describing the Indian culture which considered an important facilitating factor behind the sublime poetry of Rabindranath, Yeats stated, "The work of a supreme culture, they yet appear as much the growth of the common soil as the grass and the rushes. A tradition, where poetry and religion are the same thing, has passed through the centuries, gathering from learned and unlearned metaphor and emotion, and carried back again to the multitude the thought of the scholar and of the noble."[8][9]

Nobel Prize in 1913

editIn 1913, Rabindranath Tagore was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature. Evaluation of Tagore as a great poet was based mainly on the evaluation of Song Offerings, in addition to the recommendations that put his name on the short list. In awarding the prize to Rabindranth, the Nobel committee stated: "because of his profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful verse, by which, with consummate skill, he has made his poetic thought, expressed in his own English words, a part of the literature of the West"[10] The Nobel committee recognized him as "an author who, in conformity with the express wording of Alfred Nobel's last will and testament, had during the current year, written the finest poems «of an idealistic tendency."[11] The Nobel Committee finally quoted from Song Offering and stated that Rabindranath in thought-impelling pictures, has shown how all things temporal are swallowed up in the eternal:

Time is endless in thy hands, my lord.

There is none to count thy minutes.

Days and nights pass and ages bloom and fade like flowers.

Thou knowest how to wait.

Thy centuries follow each other perfecting a small wild flower.

We have no time to lose, and having no time, we must scramble for our chances.

We are too poor to be late.

And thus it is that time goes by,

while I give it to every querulous man who claims it,

and thine altar is empty of all offerings to the last.

At the end of the day I hasten in fear lest thy gate be shut;

but if I find that yet there is time.

(Gitanjali, No. 82)

In response to the announcement of the Nobel prize, Rabindranath sent a telegram saying, "I beg to convey to the Swedish Academy my grateful appreciation of the breadth of understanding which has brought the distant near, and has made a stranger a brother." This was read out by Mr. Clive, the-then British Chargé d'Affaires (CDA) in Sweden, at the Nobel Banquet at Grand Hôtel, Stockholm, on 10 December 1913.[12] Eight years after the Nobel Prize was awarded, Rabindranath went to Sweden in 1921 to give his acceptance speech.

Comments on Song Offerings

editThe first formal review of Song Offerings was in the Times Literary Supplement on its 7 November issue of 1912 (p. 492).[3]

References

edit- ^ Presentation Speech by the Nobel Committee

- ^ Ghosal, Sukriti. "The Language of Gitanjali: the Paradoxical Matrix" (PDF). The Criterion: An International Journal in English. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ a b Rabindranath in English - Response of the West

- ^ "Gitanjali: Selected Poems". School of Wisdom. 2010-07-30. Archived from the original on 2012-07-21. Retrieved 2012-07-11.

- ^ Song Offerings - Rabindranath Tagore, translated by Joe Winter, 1998: Writers Workshop, Calcutta, India.

- ^ Tagore, Rabindranath (2011). Gitanjali: Song Offerings. Translated by Radice, William. ISBN 978-0-670-08542-2. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ^ Basbhumi,Sydney

- ^ Gitanjali, Rabindranath Tagore, 1912, 1913

- ^ "Yeats' introduction to Tagore's Gitanji". The Fortnightly Review. 2013-05-27. Retrieved 2017-12-21.

- ^ Literature 1913

- ^ Nobel Prize in Literature 1913 – Presentation Speech

- ^ Rabindranath Tagore – Banquet Speech

External links

edit- Gitanjali (Song Offerings)

- Gitanjali (Song Offerings)

- Song Offerings

- [1] Eldritch Press version]

- Gitanjali

- Lyric number of Song Offering as sung

- Gitanjali public domain audiobook at LibriVox