The South China Sea is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean. It is bounded in the north by South China, in the west by the Indochinese Peninsula, in the east by the islands of Taiwan and northwestern Philippines (mainly Luzon, Mindoro and Palawan), and in the south by Borneo, eastern Sumatra and the Bangka Belitung Islands, encompassing an area of around 3,500,000 km2 (1,400,000 sq mi). It communicates with the East China Sea via the Taiwan Strait, the Philippine Sea via the Luzon Strait, the Sulu Sea via the straits around Palawan, and the Java Sea via the Karimata and Bangka Straits. The Gulf of Thailand and the Gulf of Tonkin are part of the South China Sea.

| South China Sea | |

|---|---|

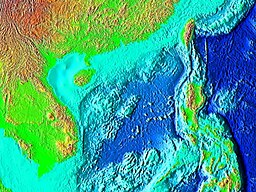

Satellite image of South China Sea | |

The northeastern portion of South China Sea | |

| Location | East Asia and Southeast Asia |

| Coordinates | 12°N 113°E / 12°N 113°E |

| Type | Sea |

| Part of | Pacific Ocean |

| River sources | |

| Basin countries | |

| Surface area | 3,500,000 square kilometres (1,400,000 sq mi) |

| Islands | List of islands in South China Sea |

| Trenches | Manila Trench |

| Settlements | Major cities

|

$3.4 trillion of the world's $16 trillion maritime shipping passed through South China Sea in 2016. Oil and natural gas reserves have been found in the area. The Western Central Pacific accounted for 14% of world's commercial fishing in 2010.

The South China Sea Islands, collectively comprising several archipelago clusters of mostly small uninhabited islands, islets (cays and shoals), reefs/atolls and seamounts numbering in the hundreds, are subject to competing claims of sovereignty by several countries. These claims are also reflected in the variety of names used for the islands and the sea.

Etymology

| South China Sea | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 南海 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Nán Hǎi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | South Sea | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 南中国海 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 南中國海 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Nán Zhōngguó Hǎi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | South China Sea | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese | Biển Đông | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hán-Nôm | 𣷷東 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | East Sea | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thai name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thai | ทะเลจีนใต้ [tʰā.lēː t͡ɕīːn tâ(ː)j] (South China Sea) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| RTGS | Thale Chin Tai | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 南支那海 or 南シナ海 (literally "South Shina Sea") | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | みなみシナかい | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Malay name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Malay | Laut Cina Selatan (لاءوت چينا سلاتن) (South China Sea) Laut Nusantara (لاءوت نوسنتارا) (Nusantara Sea) Laut Campa (لاءوت چمڤا) (Champa Sea) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Indonesian name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Indonesian | Laut Cina Selatan / Laut Tiongkok Selatan (South China Sea) Laut Natuna Utara (North Natuna Sea; Indonesian official government use; Claimed Indonesian EEZ only)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Filipino name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tagalog | Dagat Timog Tsina (South China Sea) Dagat Luzon (Luzon Sea) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Portuguese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Portuguese | Mar da China Meridional (South China Sea) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Khmer name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Khmer | សមុទ្រចិនខាងត្បូង [samut cən kʰaːŋ tʰɓoːŋ] ('South China Sea') | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tetum name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tetum | Tasi Sul Xina | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

South China Sea is the dominant term used in English for the sea, and the name in most European languages is equivalent. This name is a result of early European interest in the sea as a route from Europe and South Asia to the trading opportunities of China. In the 16th century, Portuguese sailors called it the China Sea (Mare da China); later needs to differentiate it from nearby bodies of water led to calling it South China Sea.[2] The International Hydrographic Organization refers to the sea as "South China Sea (Nan Hai)".[3]

The Yizhoushu, which was a chronicle of the Western Zhou dynasty (1046–771 BCE), gives the first Chinese name for South China Sea as Nanfang Hai (Chinese: 南方海; pinyin: Nánfāng Hǎi; lit. 'Southern Sea'), claiming that barbarians from that sea gave tributes of hawksbill sea turtles to the Zhou rulers.[4] The Classic of Poetry, Zuo Zhuan, and Guoyu classics of the Spring and Autumn period (771–476 BCE) also referred to the sea, but by the name Nan Hai (Chinese: 南海; pinyin: Nán Hǎi; lit. 'South Sea') in reference to the State of Chu's expeditions there.[4] Nan Hai, the South Sea, was one of the Four Seas of Chinese literature. There are three other seas, one for each of the four cardinal directions.[5] During the Eastern Han dynasty (23–220 CE), China's rulers called the sea Zhang Hai (Chinese: 漲海; pinyin: Zhǎng Hǎi; lit. 'distended sea').[4] Fei Hai (Chinese: 沸海; pinyin: Fèi Hǎi; lit. 'boiling sea') became popular during the Southern and Northern dynasties. Usage of the current Chinese name, Nan Hai (South Sea), gradually became widespread during the Qing dynasty.[6]

In Southeast Asia it was once called the Champa Sea or Sea of Cham, after the maritime kingdom of Champa (nowadays Central Vietnam), which flourished there before the 16th century.[7] The majority of the sea came under Japanese naval control during World War II following the military acquisition of many surrounding South East Asian territories in 1941.[citation needed] Japan calls the sea Minami Shina Kai "South China Sea". This was written 南支那海 until 2004, when the Japanese Foreign Ministry and other departments switched the spelling to 南シナ海, which has become the standard usage in Japan.[citation needed]

In China, it is called the South Sea, (南海; Nánhǎi), and in Vietnam the East Sea, Biển Đông.[8][9][10] In Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines, it was long called the South China Sea (Tagalog: Dagat Timog Tsina, Malay: Laut China Selatan), with the part within Philippine territorial waters often called the "Luzon Sea", Dagat Luzon, by the Philippines.[11]

However, following an escalation of the Spratly Islands dispute in 2011, various Philippine government agencies started using the name West Philippine Sea. A Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) spokesperson said that the sea to the east of the Philippines will continue to be called the Philippine Sea.[12] In September 2012, Philippine President Benigno Aquino III signed Administrative Order No. 29, mandating that all government agencies use the name West Philippine Sea to refer to the parts of South China Sea within the Philippines exclusive economic zone, including the Luzon Sea as well as the waters around, within and adjacent to the Kalayaan Island Group and Bajo de Masinloc, and tasked the National Mapping and Resource Information Authority to use the name in official maps.[13][14]

In July 2017, to assert its sovereignty, Indonesia renamed the northern reaches of its exclusive economic zone in the South China Sea as the North Natuna Sea, which is located north of the Indonesian Natuna Islands, bordering southern Vietnam exclusive economic zone, corresponding to southern end of South China Sea.[15] The Natuna Sea is located south of Natuna Island within Indonesian territorial waters.[16] Therefore, Indonesia has named two seas that are portions of South China Sea; the Natuna Sea located between Natuna Islands and the Lingga and Tambelan Archipelagos, and the North Natuna Sea located between the Natuna Islands and Cape Cà Mau on the southern tip of the Mekong Delta in Vietnam. There has been no agreement between China and Indonesia on what has been called the Natuna waters dispute, with China being ambiguous as to the southern limit of its area of interest.[17]

Hydrography

States and territories with borders on the sea (clockwise from north) include: the People's Republic of China, the Republic of China (Taiwan), the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia and Vietnam. Major rivers that flow into South China Sea include the Pearl, Min, Jiulong, Red, Mekong, Menam, Rajang, Baram, Kapuas, Batang Hari, Musi, Kampar, Indragiri, Pahang, Agno, Pampanga and Pasig Rivers.

The IHO in its Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition (1953), defines the limits of South China Sea as follows:[3]

On the South. The Eastern and Southern limits of Singapore and Malacca Straits [A line joining Tanjong Datok, the Southeast point of Johore (1°22′N 104°17′E / 1.367°N 104.283°E) through Horsburgh Reef to Pulo Koko, the Northeastern extreme of Bintan Island (1°13.5′N 104°35′E / 1.2250°N 104.583°E). The Northeastern coast of Sumatra] as far West as Tanjong Kedabu (1°06′N 102°58′E / 1.100°N 102.967°E) down the East coast of Sumatra to Lucipara Point (3°14′S 106°05′E / 3.233°S 106.083°E) thence to Tanjong Nanka, the Southwest extremity of Banka Island (where it transitions as Java Sea), through this island to Tanjong Berikat the Eastern point (2°34′S 106°51′E / 2.567°S 106.850°E), on to Tanjong Djemang (2°36′S 107°37′E / 2.600°S 107.617°E) in Billiton, along the North coast of this island to Tanjong Boeroeng Mandi (2°46′S 108°16′E / 2.767°S 108.267°E) and thence a line to Tanjong Sambar (3°00′S 110°19′E / 3.000°S 110.317°E) the Southwest extreme of Borneo.

On the East. From Tanjong Sambar through the West coast of Borneo to Tanjong Sampanmangio, the North point, thence a line to West points of Balabac and Secam Reefs, on to the West point of Bancalan Island and to Cape Buliluyan, the Southwest point of Palawan, through this island to Cabuli Point, the Northern point thereof, thence to the Northwest point of Busuanga and to Cape Calavite in the island of Mindoro, to the Northwest point of Lubang Island and to Point Fuego (14°08'N) in Luzon Island, through this island to Cape Engano, the Northeast point of Luzon, along a line joining this cape with the East point of Balintang Island (20°N) and to the East point of Y'Ami Island (21°05'N) thence to Garan Bi, the Southern point of Taiwan (Formosa), through this island to Santyo (25°N) its North Eastern Point.

On the North. From Fuki Kaku the North point of Formosa to Kiushan Tao (Turnabout Island) on to the South point of Haitan Tao (25°25'N) and thence Westward on the parallel of 25°24' North to the coast of Fukien.

On the West. The Mainland, the Southern limit of the Gulf of Thailand and the East coast of the Malay Peninsula.

However, in a revised draft edition of Limits of Oceans and Seas, 4th edition (1986), the International Hydrographic Organization recognized the Natuna Sea. Thus the southern limit of South China Sea would be revised from the Bangka Belitung Islands to the Natuna Islands.[18]

Geology

The sea lies above a drowned continental shelf; during recent ice ages global sea level was hundreds of metres lower, and Borneo was part of the Asian mainland.

The South China Sea opened around 45 million years ago when the "Dangerous Ground" rifted away from southern China. Extension culminated in seafloor spreading around 30 million years ago, a process that propagated to the southwest resulting in the V-shaped basin we see today. Extension ceased around 17 million years ago.[19]

Arguments have continued about the role of tectonic extrusion in forming the basin. Paul Tapponnier and colleagues have argued that as India collides with Asia it pushes Indochina to the southeast. The relative shear between Indochina and China caused the South China Sea to open.[20] This view is disputed by geologists who do not consider Indochina to have moved far relative to mainland Asia. Marine geophysical studies in the Gulf of Tonkin by Peter Clift has shown that the Red River Fault was active and causing basin formation at least by 37 million years ago in the northwest South China Sea, consistent with extrusion playing a part in the formation of the sea.[citation needed] Since opening, the South China Sea has been the repository of large sediment volumes delivered by the Mekong River, Red River and Pearl River. Several of these deltas are rich in oil and gas deposits.[citation needed]

Islands and seamounts

The South China Sea contains over 250 small islands, atolls, cays, shoals, reefs, and sandbars, most of which have no indigenous people, many of which are naturally under water at high tide, and some of which are permanently submerged. The features are:

- The Spratly Islands

- The Paracel Islands

- Pratas Island and the Vereker Banks

- The Macclesfield Bank

- The Scarborough Shoal

The Spratly Islands spread over an 810 by 900 km area covering some 175 identified insular features, the largest being Taiping Island (Itu Aba) at just over 1.3 kilometres (0.81 mi) long and with its highest elevation at 3.8 metres (12 ft).

The largest singular feature in the area of the Spratly Islands is a 100 kilometres (62 mi) wide seamount called Reed Tablemount, also known as Reed Bank, in the northeast of the group, separated from Palawan Island of the Philippines by the Palawan Trench. Now completely submerged, with a depth of 20 metres (66 ft), it was an island until it was covered about 7,000 years ago by increasing sea levels after the last ice age. With an area of 8,866 square kilometres (3,423 sq mi), it is one of the largest submerged atoll structures in the world.

Trade route

The South China Sea has historically been an important trade route between northeast Asia, China, southeast Asia, and going to India and the west.[21][22][23][24] The number of shipwrecks of trading ships that lie on the ocean's floor attest to a thriving trade going back centuries. Nine historic trade ships carrying ceramics dating back to the 10th century until the 19th century were excavated under Swedish engineer Sten Sjöstrand.[25]

$3.4 trillion of the world's $16 trillion maritime shipping passed through South China Sea in 2016.[26] The 2019 data shows that the sea carries trade equivalent to 5 per cent of global GDP.[27]

Natural resources

In 2012–2013, the United States Energy Information Administration estimates very little oil and natural gas in contested areas such as the Paracel and the Spratly Islands. Most of the proved or probable 11 billion barrels of oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas in the South China Sea exist near undisputed shorelines.[28][29]

In 2010, the Western Central Pacific (excluding the northernmost reaches of the South China Sea closest to the PRC coast) accounted for 14% of the total world catch from commercial fishing of 11.7 million tonnes. This was up from less than 4 million tonnes in 1970.[30]

China announced in May 2017 a breakthrough for mining methane clathrates, when they extracted methane from hydrates in the South China Sea, but commercial adoption may take a decade or more.[31][32]

Territorial claims

124miles

- Legend:

- Philippines: 10: Flat Island 11: Lankiam Cay 12: Loaita Cay 13: Loaita Island 14: Nanshan Island 15: Northeast Cay 16: Thitu Island 17: West York Island 18: Commodore Reef 19: Irving Reef 20: Second Thomas Shoal

- Vietnam: 21: Southwest Cay 22: Sand Cay 23: Namyit Island 24: Sin Cowe Island 25: Spratly Island 26: Amboyna Cay 27: Grierson Reef 28: Central London Reef 29: Pearson Reef 30: Barque Canada Reef 31: West London Reef 32: Ladd Reef 33: Discovery Great Reef 34: Pigeon Reef 35: East London Reef 36: Alison Reef 37: Cornwallis South Reef 38: Petley Reef 39: South Reef 40: Collins Reef 41: Lansdowne Reef 42: Bombay Castle 43: Prince of Wales Bank 44: Vanguard Bank 45: Prince Consort Bank 46: Grainger Bank 47: Alexandra Bank 48: Orleana Shoal 49: Kingston Shoal

- Malaysia: 50: Swallow Reef 51: Ardasier Reef 52: Dallas Reef 53: Erica Reef 54: Investigator Shoal 55: Mariveles Reef

Several countries have made competing territorial claims over the South China Sea. Such disputes have been regarded as Asia's most potentially dangerous point of conflict. Both the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Republic of China (ROC, commonly known as Taiwan) claim almost the entire body as their own, demarcating their claims within what is known as the "nine-dash line", which claims overlap with virtually every other country in the region. Competing claims include:

- Indonesia, Vietnam,[33] China, and Taiwan over waters northeast of the Natuna Islands

- The Philippines, China, and Taiwan over Scarborough Shoal.

- Vietnam, China, and Taiwan over waters west of the Spratly Islands. Some or all of the islands themselves are also disputed between Vietnam, China, Taiwan, Brunei, Malaysia, and the Philippines.

- The Paracel Islands are disputed between China, Taiwan and Vietnam.

- Malaysia, Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam over areas in the Gulf of Thailand.

- Singapore and Malaysia along the Strait of Johore and the Strait of Singapore.

China and Vietnam have both been vigorous in prosecuting their claims. China (various governments) and South Vietnam each controlled part of the Paracel Islands before 1974. A brief conflict in 1974 resulted in 18 Chinese and 53 Vietnamese deaths, and China has controlled the whole of Paracel since then. The Spratly Islands have been the site of a naval clash, in which over 70 Vietnamese sailors were killed just south of Chigua Reef in March 1988. Disputing claimants regularly report clashes between naval vessels,[34] and these now also include airspace incidents.[35]

ASEAN in general, and Malaysia in particular, have been keen to ensure that the territorial disputes within the South China Sea do not escalate into armed conflict. As such, joint development authorities have been set up in areas of overlapping claims to jointly develop the area and divide the profits equally without settling the issue of sovereignty over the area. This is true particularly in the Gulf of Thailand. Generally, China has preferred to resolve competing claims bilaterally,[36] while some ASEAN countries prefer multilateral talks,[37] believing that they are disadvantaged in bilateral negotiations with the much larger China and that because many countries claim the same territory only multilateral talks could effectively resolve the competing claims.[38]

The overlapping claims over Pedra Branca or Pulau Batu Putih including the neighbouring Middle Rocks by both Singapore and Malaysia were settled in 2008 by the International Court of Justice, awarding Pedra Branca/Pulau Batu Puteh to Singapore and the Middle Rocks to Malaysia.[39] In July 2010, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton called for China to resolve the territorial dispute. China responded by demanding the US keep out of the issue. This came at a time when both countries had been engaging in naval exercises in a show of force to the opposing side, which increased tensions in the region.[34] The US Department of Defense released a statement on August 18 where it opposed the use of force to resolve the dispute, and accused China of assertive behaviour.[40] On July 22, 2011, one of India's amphibious assault vessels, the INS Airavat which was on a friendly visit to Vietnam, was reportedly contacted at a distance of 45 nautical miles (83 km) from the Vietnamese coast in the disputed South China Sea on an open radio channel by a vessel identifying itself as the Chinese Navy and stating that the ship was entering Chinese waters.[41][42] The spokesperson for the Indian Navy clarified that as no ship or aircraft was visible from INS Airavat it proceeded on her onward journey as scheduled. The Indian Navy further clarified that "[t]here was no confrontation involving the INS Airavat. India supports freedom of navigation in international waters, including in the South China Sea, and the right of passage in accordance with accepted principles of international law. These principles should be respected by all."[41]

In September 2011, shortly after China and Vietnam had signed an agreement seeking to contain a dispute over the South China Sea, India's state-run explorer, Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC) said that its overseas investment arm ONGC Videsh Limited had signed a three-year deal with PetroVietnam for developing long-term cooperation in the oil sector[43] and that it had accepted Vietnam's offer of exploration in certain specified blocks in the South China Sea.[44] In response, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Jiang Yu issued a protest.[45][46] The spokesman of the Ministry of External Affairs of the Government of India responded by saying that "The Chinese had concerns but we are going by what the Vietnamese authorities have told us and have conveyed this to the Chinese."[45] The Indo-Vietnamese deal was also denounced by the Chinese state-run newspaper Global Times.[44][46]

In 1999, Taiwan claimed the entirety of the South China Sea islands under the Lee Teng-hui administration.[47] The entire subsoil, seabed and waters of the Paracels and Spratlys are claimed by Taiwan.[48]

In 2012 and 2013, Vietnam and Taiwan butted heads against each other over anti-Vietnamese military exercises by Taiwan.[49]

In May 2014, China established an oil rig near the Paracel Islands, leading to multiple incidents between Vietnamese and Chinese ships.[50][51] Vietnamese analysis identifies this change in strategy generating on going incidents as occurring since 2012.[35]

In December 2018, retired Chinese admiral Luo Yuan proposed that a possible solution to tensions with the United States in the South China Sea would be to sink one or two United States Navy aircraft carriers to break US morale.[52][53][54][55] Also in December 2018, Chinese commentator and Senior Colonel in the People's Liberation Army Air Force, Dai Xu suggested that China's navy should ram United States Navy ships sailing in the South China Sea.[52][56]

The US, although not a signatory to UNCLOS, has maintained its position that its naval vessels have consistently sailed unhindered through the South China Sea and will continue to do so.[57] At times US warships have come within the 12 nautical-mile limit of Chinese-controlled islands (such as the Paracel Islands), arousing China's ire.[58] During the US Chief of Naval Operations' visit to China in early 2019, he and his Chinese counterpart worked out rules of engagement, whenever American warships and Chinese warships met up on the high seas.[59]

On 26 June 2020, the 36th Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Summit was held virtually. Vietnam, as the Chairman of the Summit, released the Chairman's Statement. The statement said the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea is "the basis for determining maritime entitlements, sovereign rights, jurisdiction and legitimate interests over maritime zones, and the 1982 UNCLOS sets out the legal framework within which all activities in the oceans and seas must be carried out."[60]

2016 arbitration

In January 2013, the Philippines initiated arbitration proceedings against China (PRC) over issues surrounding the nine-dash line, characterization of maritime features, and EEZ.[61][62][63][64][65] China did not participate in the arbitration.[66]: 127

On 12 July 2016, an arbitral tribunal ruled in favor of the Philippines on most of its submissions. It clarified that it would not "rule on any question of sovereignty over land territory and would not delimit any maritime boundary between the Parties" but concluded that China had not historically exercised exclusive control within the nine-dash line, hence has "no legal basis" to claim "historic rights" over the resources.[67] It also concluded that China's historic rights claims over the maritime areas (as opposed to land masses and territorial waters) inside the nine-dash line would have no lawful effect outside of what's entitled to under UNCLOS.[68] It criticized China's land reclamation projects and its construction of artificial islands in the Spratly Islands, saying that it had caused "severe harm to the coral reef environment".[69] Finally, it characterized Taiping Island and other features of the Spratly Islands as "rocks" under UNCLOS, and therefore are not entitled to a 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone.[70] The arbitral tribunal decision was ruled as final and non-appealable by either country.[71][72]

China rejected the ruling, calling it "ill-founded".[73] China's response was to ignore the arbitration result and to continue pursuing bilateral discussions with the Philippines.[66]: 128

Taiwan, which currently administers Taiping Island, the largest of the Spratly Islands, also rejected the ruling.[74] As of November 2023[update], 26 governments support the ruling, 17 issued generally positive statements noting the ruling but not called for compliance, and eight rejected it.[75] The governments in support are Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, India, Ireland, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, the Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States; the governments in opposition are China, Montenegro, Pakistan, Russia, Sudan, Syria, Taiwan, and Vanuatu.[75][76] The United Nations itself does not have a position on the legal and procedural merits of the case or on the disputed claims, and the Secretary-General expressed his hope that the continued consultations on a Code of Conduct between ASEAN and China under the framework of the Declaration of the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea will lead to increased mutual understanding among all the parties.[77]

See also

References

- ^ Indonesia, B. B. C. "China Komentari Penamaan Laut Natuna Utara oleh Indonesia". detiknews.

- ^ Tønnesson, Stein (2005). "Locating the South China Sea". In Kratoska, Paul H.; Raben, Remco; Nordholt, Henk Schulte (eds.). Locating Southeast Asia: Geographies of Knowledge and Politics of Space. Singapore University Press. p. 204. ISBN 9971-69-288-0.

The European name 'South China Sea' ... is a relic of the time when European seafarers and mapmakers saw this sea mainly as an access route to China ... European ships came, in the early 16th century, from Hindustan (India) ... The Portuguese captains saw the sea as the approach to this land of China and called it Mare da China. Then, presumably, when they later needed to distinguish between several China seas, they differentiated between the 'South China Sea', ...

- ^ a b "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. § 49. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ a b c Shen, Jianming (2002). "China's Sovereignty over the South China Sea Islands: A Historical Perspective". Chinese Journal of International Law. 1 (1): 94–157. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.cjilaw.a000432.

- ^ Chang, Chun-shu (2007). The Rise of the Chinese Empire: Nation, State, and Imperialism in Early China, ca. 1600 B.C. – A.D. 8. University of Michigan Press. pp. 263–264. ISBN 978-0-472-11533-4.

- ^ 華林甫 (Hua Linfu), 2006. 插圖本中國地名史話 (An illustrated history of Chinese place names). 齊鲁書社 (Qilu Publishing), page 197. ISBN 7533315464

- ^ Bray, Adam (June 18, 2014). "The Cham: Descendants of Ancient Rulers of South China Sea Watch Maritime Dispute From Sidelines – The ancestors of Vietnam's Cham people built one of the great empires of Southeast Asia". National Geographic. Archived from the original on June 20, 2014.

- ^ "VN and China pledge to maintain peace and stability in East Sea". Socialist Republic of Vietnam Government Web Portal.

- ^ "FM Spokesperson on FIR control over East Sea". Embassy of Vietnam in USA. March 11, 2001.

- ^ "The Map of Vietnam". Socialist Republic of Vietnam Government Web Portal. Archived from the original on 2006-10-06.

- ^ John Zumerchik; Steven Laurence Danver (2010). Seas and Waterways of the World: An Encyclopedia of History, Uses, and Issues. ABC-CLIO. p. 259. ISBN 978-1-85109-711-1.

- ^ Quismundo, Tarra (2011-06-13). "South China Sea renamed in the Philippines". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved 2011-06-14.

- ^ "Administrative Order No. 29, s. 2012". Official Gazette. Government of the Philippines. September 5, 2012. Archived from the original on May 18, 2018. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- ^ West Philippine Sea Limited To Exclusive Economic Zone Archived 2021-03-07 at the Wayback Machine, September 14, 2012, International Business Times

- ^ Prashanth Parameswaran (17 July 2017). "Why Did Indonesia Just Rename Its Part of the South China Sea?". The Diplomat.

- ^ Tom Allard; Bernadette Christina Munthe (14 July 2017). "Asserting sovereignty, Indonesia renames part of South China Sea". Reuters.

- ^ Agusman, Damos Dumoli (2023). "Natuna Waters: Explaining a Flashpoint between Indonesia and China". Indonesian Journal of International Law. 20 (4): 531–562. doi:10.17304/ijil.vol20.4.1 (inactive 1 November 2024). ISSN 2356-5527.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link): 555 - ^ "Limits of Ocean and Seas Special Publication 23 Draft 4th Edition" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1986. pp. 108–109. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-04-30. Retrieved 2017-07-17.

- ^ Trần Tất Thắng; Tống Duy Thanh; Vũ Khúc; Trịnh Dánh; Đào Đình Thục; Trần Văn Trị; Lê Duy Bách (2000). Lexicon of Geological Units of Viet Nam. Department of Geology and Mineral of Việt Nam.

- ^ Jon Erickson; Ernest Hathaway Muller (2009). Rock Formations and Unusual Geologic Structures: Exploring the Earth's Surface. Infobase Publishing. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-4381-0970-1.

- ^ "The Portuguese as the First Maritime Power". Humanities 54, Harvard University. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ "Central Themes | Asia for Educators | Columbia University". afe.easia.columbia.edu. Retrieved 2024-05-07.

- ^ "Beyond diplomacy. Japan and Vietnam during the 17th and 18th centuries | IIAS". www.iias.asia. Retrieved 2024-05-07.

- ^ "Japan and Vietnam -Archival Records on Our History-". www.archives.go.jp. Retrieved 2024-05-07.

- ^ Shipwrecks

- "STEN SJÖSTRAND COLLECTION (Discovery and salvage of four Ming dynasty Chinese shipwrecks, Royal Nanhai, Nanyang, Xuande and Longquan loaded with stoneware and porcelain, made between 1440 and 1470, from e.g., Thailand, China and Vietnam)". mingwrecks.com. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- Rodrigo, Jennifer. History hunter underwater Archived 2022-03-14 at the Wayback Machine, New Straits Times. 7/12/2004

- "Rare Ming dynasty ceramics found in shipwrecks". CNN.com. September 24, 1996.

- "Race For Ruins". Newsweek. May 18, 2002.

- ^ "How Much Trade Transits the South China Sea?". Center for Strategic and International Studies. 2017-08-02.

- ^ "There are bigger shipping choke points than Suez". Australian Financial Review. 2024-01-15. Retrieved 2024-05-07.

- ^ "Contested areas of South China Sea likely have few conventional oil and gas resources – Today in Energy – U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". Energy Information Administration. Archived from the original on 23 May 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ "All those oil and gas deposits everyone wants in the South China Sea may not even be there". Foreign Policy. 5 April 2013. Archived from the original on 23 May 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ World review of fisheries and aquaculture (PDF). Rome: Food and Agriculture Organisation. 2012. pp. 55–59. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 August 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- ^ "China claims breakthrough in 'flammable ice'". BBC News. 19 May 2017.

- ^ Robbie Gramer; Keith Johnson (29 January 2024). "China Taps Lode of 'Fire Ice' in South China Sea".

- ^ Randy Mulyanto (2020-11-02). "Vietnamese ships in Indonesian waters show extent of Asean maritime disputes". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ a b Scobellfirst =A. (2018). "The South China Sea and US-China Rivalry". Political Science Quarterly. 133 (2): 199–224. doi:10.1080/23311983.2024.2383107.: 206–215

- ^ a b Nguyễn, A.C.; Phạm, M.T.; Nguyễn, V.H.; Trần, B.H. (2024). "Explaining the increase of China's power in the South China Sea through international relation theories". Cogent Arts & Humanities. 11 (1). 2383107. doi:10.1080/23311983.2024.2383107.

- ^ "Direct bilateral dialogue 'best way to solve disputes' – China.org.cn". www.china.org.cn.

- ^ Resolving S.China Sea disputes pivotal to stability: Clinton AFP News, archived from the original on 2010-07-27)

- ^ Wong, Edward (February 5, 2010). "Vietnam Enlists Allies to Stave Off China's Reach". The New York Times.

- ^ Lathrop, Coalter G. (2008). "Sovereignty over Pedra Branca/Pulau Batu Puteh, Middle Rocks and South Ledge". The American Journal of International Law. 102 (4): 828–834. doi:10.2307/20456682. JSTOR 20456682. S2CID 142147633.

- ^ Sinaga, Lidya Christin (2015). "China's Assertive Foreign Policy in South China Sea Under XI Jinping: Its Impact on United States and Australian Foreign Policy". Journal of ASEAN Studies. 3 (2): 133–149. doi:10.21512/jas.v3i2.770. ISSN 2338-1361.

- ^ a b "India-China face-off in South China Sea: Report". dna. 2 September 2011.

- ^ "Paper no. 4677 INS Airavat Incident: What does it Portend?". South Asia Analysis Group. 2 September 2011. Archived from the original on 2012-03-30.

- ^ GatewayHouse (2015-06-11). "How India is Impacted by China's Assertiveness in the S. China Sea". Gateway House. Retrieved 2017-06-02.

- ^ a b "China paper warns India off Vietnam oil deal". Reuters India. 16 October 2011. Archived from the original on 25 July 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ a b B. Raman (17 September 2011). "South China Sea: India should avoid rushing in where even US exercises caution". South Asia Analysis Group. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011.

- ^ a b Ananth Krishnan (15 September 2011). "China warns India on South China Sea exploration projects". The Hindu.

- ^ Taiwan sticks to its guns, to U.S. chagrin, July 14, 1999.

- ^ "Taiwan reiterates Paracel Islands sovereignty claim". Taipei Times. 11 May 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- ^ Photo: Taiwan military exercises with Vietnam as an imaginary enemy generals admit Taiping Island, September 5, 2012.

Vietnam's angry at Taiwan as it stages live-fire drill in the Spratlys, 12 August 2012.

Vietnam Demands Taiwan Cancel Spratly Island Live Fire Archived 2016-08-26 at the Wayback Machine, March 1, 2013.

Taiwan unmoved by Vietnam's protest against Taiping drill, September 5, 2012

- ^ "Q&A: South China Sea dispute". BBC. 12 July 2016.

- ^ Bloomberg News (6 June 2014). "Vietnam Says China Still Ramming Boats, Airs Sinking Video". Bloomberg. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ a b Lockie, Alex (January 11, 2019). "China sets the stage for a 'bloody nose' attack on US aircraft carriers, but it would backfire horribly". Business Insider.

- ^ Hendrix, Jerry (January 4, 2019). "China should think twice before threatening to attack Americans". Fox News.

- ^ Chang, Gordon G. (December 31, 2018). "Forty Years After U.S. Recognition, China Is 'America's Greatest Foreign Policy Failure'". The Daily Beast.

- ^ "罗援少将在2018军工榜颁奖典礼与创新峰会上的演讲 – Major General Luo Yuan's speech at the 2018 Military Industry Awards Ceremony and Innovation Summit". kunlunce.com/. December 25, 2018. Archived from the original on March 31, 2019. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

现在美国有11艘航空母舰,我们是不是要发展12艘航母,才能跟美国抗衡呢?我觉得这种思路错了,我们不能搞军备竞赛。历史的经验告诉我们,美国最怕死人。我们现在有东风21D、东风26导弹,这是航母杀手锏,我们击沉它一艘航母,让它伤亡5000人/ Now there are 11 aircraft carriers in the United States. Do we want to develop 12 aircraft carriers to compete with the United States? I think this kind of thinking is wrong. We can't engage in an arms race. Historical experience tells us that the United States is most afraid of the dead. We now have Dongfeng 21D and Dongfeng 26 missiles. This is the aircraft carrier killer. If we sink an aircraft carrier, it will kill 5,000 people; if we sink two ships, we kill 10,000 people.

- ^ Deaeth, Duncan (December 8, 2018). "Senior Chinese military official urges PLAN to attack US naval vessels in S. China Sea". Taiwan News.

- ^ US Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral John M. Richardson, John M. Richardson: "Maintaining Maritime Superiority" on YouTube, Lecture at Atlantic Council's Scowcroft Center. / Feb 2019, minutes 38:22–41:25; 49:39–52:00.

- ^ Goelman, Zachary (7 January 2019). "U.S. Navy ship sails in disputed South China Sea amid trade talks with Beijing". Reuters.

- ^ US Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral John M. Richardson, John M. Richardson: "Maintaining Maritime Superiority" on YouTube, Lecture at Atlantic Council's Scowcroft Center. / Feb 2019.

- ^ B Pitlo III, Lucio (3 July 2020). "ASEAN stops pulling punches over South China Sea". Archived from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d "PCA Case No 2013-19" (PDF). Permanent Court of Arbitration. 12 July 2016.

- ^ PCA Award, Section V(F)(d)(264, 266, 267), p. 113.[61]

- ^ PCA Award, Section II(A), p. 11.[61]

- ^ "Timeline: South China Sea dispute". Financial Times. 12 July 2016. Archived from the original on 2022-12-10.

- ^ Beech, Hannah (11 July 2016). "China's Global Reputation Hinges on Upcoming South China Sea Court Decision". TIME.

- ^ a b Wang, Frances Yaping (2024). The Art of State Persuasion: China's Strategic Use of Media in Interstate Disputes. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780197757512.

- ^ "Press Release: The South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of the Philippines v. The People's Republic of China)" (PDF). PCA. 12 July 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ PCA Award, Section V(F)(d)(278), p. 117.[61]

- ^ Tom Phillips; Oliver Holmes; Owen Bowcott (12 July 2016). "Beijing rejects tribunal's ruling in South China Sea case". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 July 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Chow, Jermyn (12 July 2016). "Taiwan rejects South China Sea ruling, says will deploy another navy vessel to Taiping". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ "A UN-appointed tribunal dismisses China's claims in the South China Sea". The Economist. 12 July 2016. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ Perez, Jane (12 July 2016). "Beijing's South China Sea Claims Rejected by Hague Tribunal". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 July 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ "South China Sea: Tribunal backs case against China brought by Philippines". BBC. 12 July 2016. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ Jun Mai; Shi Jiangtao (12 July 2016). "Taiwan-controlled Taiping Island is a rock, says international court in South China Sea ruling". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 15 July 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ a b "Arbitration Support Tracker | Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative". Center for Strategic and International Studies. Archived from the original on 15 July 2024. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ Declaration by the High Representative on behalf of the EU on the Award rendered in the Arbitration between the Republic of the Philippines and the People's Republic of China (archived from the original on February 9, 2018)

- ^ "Daily Press Briefing by the Office of the Spokesperson for the Secretary-General". United Nations. 12 July 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

Further reading

- Beckman, Robert; et al., eds. (2013). Beyond Territorial Disputes in the South China Sea: Legal Frameworks for the Joint Development of Hydrocarbon Resources. Edward Elgar. ISBN 978-1-78195-593-2.

- Francois-Xavier Bonnet, Geopolitics of Scarborough Shoal, Irasec Discussion Paper 14, November 2012

- C. Michael Hogan (2011) South China Sea Topic ed. P. Saundry. Ed.-in-chief C.J. Cleveland. Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington DC

- Clive Schofield et al., From Disputed Waters to Seas of Opportunity: Overcoming Barriers to Maritime Cooperation in East and Southeast Asia (July 2011)

- UNEP (2007). Review of the Legal Aspects of Environmental Management in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand. UNEP/GEF/SCS Technical Publication No. 9.

- Wang, Gungwu (2003). The Nanhai Trade: Early Chinese Trade in the South China Sea. Marshall Cavendish International. ISBN 9789812102416.

- Keyan Zou (2005). Law of the sea in East Asia: issues and prospects. London/New York: Rutledge Curzon. ISBN 0-415-35074-3

- United States. Congress. (2014). Maritime Sovereignty in the East and South China Seas: Joint Hearing before the Subcommittee on Seapower and Projection Forces of the Committee on Armed Services Meeting Jointly with the Subcommittee on Asia and the Pacific of the Committee on Foreign Affairs (Serial No. 113-137), House of Representatives, One Hundred Thirteenth Congress, Second Session, Hearing held January 14, 2014

External links

- ASEAN and the South China Sea: Deepening Divisions Q&A with Ian J. Storey (July 2012)

- Rising Tensions in the South China Sea, June 2011 Q&A with Ian J. Storey

- News collections on The South China Sea on China Digital Times

- The South China Sea on Google Earth – featured on Google Earth's Official Blog

- South China Sea Virtual Library – online resource for students, scholars and policy-makers interested in South China Sea regional development, environment, and security issues.

- Energy Information Administration – The South China Sea

- Tropical Research and Conservation Centre – The South China Sea

- Weekly Piracy Report

- Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

- UNEP/GEF South China Sea Knowledge Documents

- Audio Radio communication between United States Navy Boeing P-8A Poseidon aircraft operating under international law and the Chinese Navy warnings.

- A 1775 Chart of the China Sea | Southeast Asia Digital Library