Bitches Brew is a studio album by the American jazz trumpeter, composer, and bandleader Miles Davis. It was recorded from August 19 to 21, 1969, at Columbia's Studio B in New York City and released on March 30, 1970, by Columbia Records. It marked his continuing experimentation with electric instruments that he had featured on his previous record, the critically acclaimed In a Silent Way (1969). With these instruments, such as the electric piano and guitar, Davis departed from traditional jazz rhythms in favor of loose, rock-influenced arrangements based on improvisation. The final tracks were edited and pieced together by producer Teo Macero.

| Bitches Brew | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | March 30, 1970[1] | |||

| Recorded | August 19–21, 1969 | |||

| Studio | Columbia 52nd Street (New York City) | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 93:57 | |||

| Label | Columbia | |||

| Producer | Teo Macero | |||

| Miles Davis chronology | ||||

| ||||

The album initially received a mixed critical and commercial response, but it gained momentum and became Davis's highest-charting album on the U.S. Billboard 200, peaking at No. 35. In 1971, it won a Grammy Award for Best Large Jazz Ensemble Album.[7] In 1976, it became Davis's first gold album to be certified by the Recording Industry Association of America.[8][9]

In subsequent years, Bitches Brew gained recognition as one of jazz's greatest albums and a progenitor of the jazz rock genre, as well as a major influence on rock and '70s crossover musicians.[4] In 1998, Columbia released The Complete Bitches Brew Sessions,[10] a four-disc box set that includes the original album and previously unreleased material. In 2003, the album was certified platinum, reflecting shipments of one million copies.

Background and recording

editBy 1969, Davis's core working band consisted of Wayne Shorter on soprano saxophone, Dave Holland on bass, Chick Corea on electric piano, and Jack DeJohnette on drums.[11] The group, minus DeJohnette, recorded In a Silent Way (1969), which also featured Joe Zawinul, John McLaughlin, Tony Williams, and Herbie Hancock. The album marked the beginning of Davis's "electric period", incorporating instruments such as the electric piano, guitar, and jazz fusion styles.[11] For his next studio album, Davis wished to explore his electronic and fusion style even further. While touring with his five-piece from the spring to August 1969, he introduced new pieces for his band to play, including early versions of what became "Miles Runs the Voodoo Down", "Sanctuary", and "Spanish Key".[12] At this point in his career Davis was influenced by contemporary rock and funk music, Zawinul's playing with Cannonball Adderley, and the work of English composer Paul Buckmaster.[13]

In August 1969, Davis gathered his band for a rehearsal, one week prior to the booked recording sessions. As well as his five-piece, they were joined by Zawinul, McLaughlin, Larry Young, Lenny White, Don Alias, Juma Santos, and Bennie Maupin.[12] Davis had written simple chord lines, at first for three pianos, which he expanded into a sketch of a larger scale composition. He presented the group with some "musical sketches" and told them they could play anything that came to mind as long as they played off of his chosen chords.[14] Davis had not arranged each piece because he was unsure of the direction the album was to take; he wanted whatever was produced to come from an improvisational process, "not some prearranged shit."[15]

Davis booked Columbia's Studio B in New York City from August 19–21, 1969.[12] The session on August 19 began at 10 a.m., the band playing "Bitches Brew" first. Everyone was set up in a half-circle with Davis and Shorter in the middle. In Lenny White’s words:

"It was like an orchestra, and Miles was our conductor. We wore headphones. We had to be able to hear each other. There were no guests at that session. No photos allowed. But there was one guest that nobody talked about, Max Roach. All live recording, no overdubs. 10 a.m. to 1 p.m., for three days."

— Lenny White, [1]

As usual with Davis's recording sessions during this period, tracks were recorded in sections.[12] Davis gave a few instructions: a tempo count, a few chords or a hint of melody, and suggestions as to mood or tone. Davis liked to work this way; he thought it forced musicians to pay close attention to one another, to their own performances, or to Davis's cues, which could change from moment to moment. On the quieter passages of "Bitches Brew", for example, Davis's voice is audible giving instructions to the musicians, snapping his fingers to indicate tempo, telling the musicians to "Keep it tight" in his distinctive voice, or instructing individuals when to solo — e.g., saying "John" during the title track.[16] "John McLaughlin" and "Sanctuary" were also recorded during the August 19 session. Towards the end, the group rehearsed "Pharaoh's Dance".[12]

Despite his reputation as a "cool", melodic improviser, much of Davis's playing on this album is aggressive and explosive, often playing fast runs and venturing into the upper register of the trumpet. His closing solo on "Miles Runs the Voodoo Down" is particularly noteworthy in this regard. Davis did not perform on the short piece "John McLaughlin".

Album title

editIt is not known where the album title came from, and there are various theories as to where it originates.[17] Some believe it was a reference to women in Davis's life who were introducing him to cultural changes in the 1960s.[17][18][19] Other explanations have been given.[17]

Post-production

editSignificant editing was made to the recorded music. Short sections were spliced together to create longer pieces, and various effects were applied to the recordings. Paul Tingen reports:[20]

Bitches Brew also pioneered the application of the studio as a musical instrument, featuring stacks of edits and studio effects that were an integral part of the music. Miles and his producer, Teo Macero, used the recording studio in radical new ways, especially in the title track and the opening track, "Pharaoh's Dance". There were many special effects, like tape loops, tape delays, reverb chambers and echo effects. Through intensive tape editing, Macero concocted many totally new musical structures that were later imitated by the band in live concerts. Macero, who has a classical education and was most likely inspired by '50s and '60s French musique concrète experiments, used tape editing as a form of arranging and composition. "Pharaoh's Dance" contains 19 edits – its famous stop-start opening is entirely constructed in the studio, using repeat loops of certain sections. Later on in the track there are several micro-edits: for example, a one-second-long fragment that first appears at 8:39 is repeated five times between 8:54 and 8:59. The title track contains 15 edits, again with several short tape loops of, in this case, five seconds (at 3:01, 3:07 and 3:12). Therefore, Bitches Brew not only became a controversial classic of musical innovation, it also became renowned for its pioneering use of studio technology.

Though Bitches Brew was in many ways revolutionary, perhaps its most important innovation was rhythmic. The rhythm section for this recording consists of two bassists (one playing bass guitar, the other double bass), two to three drummers, two to three electric piano players, and a percussionist, all playing at the same time.[21] As Paul Tanner, Maurice Gerow, and David Megill explain, "like rock groups, Davis gives the rhythm section a central role in the ensemble's activities. His use of such a large rhythm section offers the soloists wide but active expanses for their solos."[21]

Tanner, Gerow and Megill further explain that

"the harmonies used in this recording move very slowly and function modally rather than in a more tonal fashion typical of mainstream jazz.... The static harmonies and rhythm section's collective embellishment create a very open arena for improvisation. The musical result flows from basic rock patterns to hard bop textures, and at times, even passages that are more characteristic of free jazz."[21]

The solo voices heard most prominently on this album are the trumpet and the soprano saxophone, respectively of Miles and Wayne Shorter. Notable also is Bennie Maupin's bass clarinet present on four tracks.

The technology of recording, analog tape, disc mastering, and inherent recording time constraints had, by the late sixties, expanded beyond previous limitations and sonic range for the stereo vinyl album, and Bitches Brew reflects this. Its long-form performances include improvised suites with rubato sections, tempo changes or the long, slow crescendo more common to a symphonic orchestral piece or Indian raga form than the three-minute rock song. Starting in 1969, Davis's concerts included some of the material that would become Bitches Brew.[22]

Release

editBitches Brew was released in March 1970. It gained commercial momentum for the next four months and peaked at No. 35 on the U.S. Billboard 200 for the week of July 4, 1970. This remains Davis's second best performance on the chart behind Kind of Blue, which has peaked at number 3 on Vinyl and number 12 in 2020.[23] On September 22, 2003, the album was certified platinum by the RIAA for selling one million copies in the U.S.

In addition to the standard stereo version, the album was also mixed for quadraphonic sound. Columbia released a quad LP version, using the SQ matrix system, in 1971. Sony reissued the album in Japan in 2018 on the Super Audio CD format containing both the complete stereo and quadraphonic mixes.[24]

Reception and legacy

edit| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [4] |

| Christgau's Record Guide | A−[25] |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | [26] |

| Entertainment Weekly | A[27] |

| Mojo | [27] |

| MusicHound Jazz | 5/5[28] |

| The Penguin Guide to Jazz | [29] |

| Pitchfork | 9.5/10[30] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | [31] |

| Sputnikmusic | 5/5[32] |

| Tom Hull – on the Web | A−[33] |

Reviewing for Rolling Stone in 1970, Langdon Winner said Bitches Brew shows Davis's music expanding in "beauty, subtlety and sheer magnificence", finding it "so rich in its form and substance that it permits and even encourages soaring flights of imagination by anyone who listens". He concluded that the album would "reward in direct proportion to the depth of your own involvement".[34] Village Voice critic Robert Christgau deemed it "good music that's very much like jazz and something like rock",[35] naming it the year's best jazz album and Davis "jazzman of the year" in his ballot for Jazz & Pop magazine.[36] Years later, he had lost some enthusiasm about the album; in Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies (1981), he called Bitches Brew "a brilliant wash of ideas, so many ideas that it leaves an unfocused impression", with Tony Williams' steadier rock rhythms from In a Silent Way replaced by "subtle shades of Latin and funk polyrhythm that never gather the requisite fervor". He concluded that the music sounded "enormously suggestive, and never less than enjoyable, but not quite compelling. Which is what rock is supposed to be."[25]

Selling more than one million copies since it was released, Bitches Brew was viewed by some writers in the 1970s as the album that spurred jazz's renewed popularity with mainstream audiences that decade. As Michael Segell wrote in 1978, jazz was "considered commercially dead" by the 1960s until the album's success "opened the eyes of music-industry executives to the sales potential of jazz-oriented music". This led to other fusion records that "refined" Davis's new style of jazz and sold millions of copies, including Head Hunters (1973) by Herbie Hancock and George Benson's 1976 album Breezin'.[37] Tom Hull, who would later become a jazz critic, has said, "Back in the early '70s we used to listen to Bitches Brew as late night chill-out music – about the only jazz I ran into at the time."[38] According to independent scholar Jane Garry, Bitches Brew defined and popularized the jazz fusion genre, also known as jazz-rock, but it was hated by a number of purists.[2] Jazz critic and producer Bob Rusch recalled, "This to me was not great Black music, but I cynically saw it as part and parcel of the commercial crap that was beginning to choke and bastardize the catalogs of such dependable companies as Blue Note and Prestige.... I hear it 'better' today because there is now so much music that is worse."[39] Despite the controversy the album stirred among the jazz community, it nonetheless topped DownBeat's annual critics' poll in 1970.[40]

The Penguin Guide to Jazz called Bitches Brew "one of the most remarkable creative statements of the last half-century, in any artistic form. It is also profoundly flawed, a gigantic torso of burstingly noisy music that absolutely refuses to resolve itself under any recognized guise."[29] In 2003, the album was ranked number 94 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time. Nine years later, it went down one spot.[41] In the 2020 list, it climbed to number 87.[42] Along with this accolade, the album has been ranked at or near the top of several other magazines' "best albums" lists in disparate genres.[citation needed] The album was also included in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[43]

Experimental jazz drummer Bobby Previte considered Bitches Brew to be "groundbreaking": "How much groundbreaking music do you hear now? It was music that you had that feeling you never heard quite before. It came from another place. How much music do you hear now like that?"[44] Thom Yorke, singer of the English rock band Radiohead, cited it as an influence on their 1997 album OK Computer: "It was building something up and watching it fall apart, that's the beauty of it. It was at the core of what we were trying to do."[45] The singer Bilal names it among his 25 favorite albums, citing Davis's stylistic reinvention.[46] Rock and jazz musician Donald Fagen criticized the album as "essentially just a big trash-out for Miles ... To me it was just silly, and out of tune, and bad. I couldn't listen to it. It sounded like [Davis] was trying for a funk record, and just picked the wrong guys. They didn't understand how to play funk. They weren't steady enough."[47]

Track listing

edit| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Recording date | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Pharaoh's Dance" | Joe Zawinul | August 21, 1969 | 20:07 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Recording date | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Bitches Brew" | Miles Davis | August 19, 1969 | 27:00 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Recording date | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Spanish Key" | Davis | August 21, 1969 | 17:30 |

| 2. | "John McLaughlin" | Davis | August 19, 1969 | 4:23 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Recording date | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Miles Runs the Voodoo Down" | Davis | August 20, 1969 | 14:03 |

| 2. | "Sanctuary" | Wayne Shorter | August 19, 1969 | 10:54 |

| Total length: | 93:57 | |||

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Recording date | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7. | "Feio" | Shorter | January 28, 1970 | 11:51 |

Personnel

editMusicians

edit|

"Bitches Brew"

|

"Spanish Key"

|

Production

edit- Teo Macero – producer

- Frank Laico – engineer (August 19, 1969 session)

- Stan Tonkel – engineer (all other sessions)

- Mark Wilder – mastering

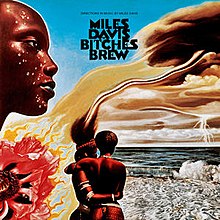

- Mati Klarwein – cover painting

- Bob Belden – reissue producer

- Michael Cuscuna – reissue producer

Charts

edit| Chart | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Belgian Albums (Ultratop Flanders)[48] | 80 |

| Portuguese Albums (AFP)[49] | 49 |

| UK Albums (OCC)[50] | 71 |

| US Billboard 200[51] | 35 |

| US Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums (Billboard)[52] | 4 |

| US Top Jazz Albums (Billboard)[53] | 1 |

Certifications

edit| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom (BPI)[54] sales since 1999 |

Gold | 100,000* |

| United States (RIAA)[55] | Platinum | 1,000,000^ |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

See also

edit- Bitches Brew Live (Sony/Legacy, 2011)

- Memo from producer asking for advice about the title.[56]

References

edit- ^ Miles Davis.com

- ^ a b Garry, Jane (2005). "Jazz". In Haynes, Gerald D. (ed.). Encyclopedia of African American Society. SAGE Publications. p. 465.

- ^ Spencer, Neil (September 4, 2010). "Miles Davis: The muse who changed him, and the heady Brew that rewrote jazz". The Guardian. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- ^ a b c Jurek, Thom. Review: Bitches Brew. AllMusic. Retrieved on 2010-10-08.

- ^ Hoskyns, Barney (March 8, 2016). Small Town Talk: Bob Dylan, The Band, Van Morrison, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix and Friends in the Wild Years of Woodstock. Da Capo Press. p. 227. ISBN 9780306823213.

- ^ Forrest, Ben. "Miles Davis explained how "prejudice" fuelled his music". Far Out. Retrieved 21 July 2024.

- ^ "Past Winners Search | GRAMMY.com". grammy.com. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ^ Bitches Brew: Miles Davis' Shot Heard 'Round the Jazz World – ColumbiaJazz Archived 2008-07-05 at the Wayback Machine. Columbia. Retrieved on 2008-08-30.

- ^ Miles Electric: A Different Kind of Blue (DVD) – PopMatters. PopMatters. Retrieved on 2008-08-30.

- ^ Bush, John (2011). "The Complete Bitches Brew Sessions (August 1969 – February 1970) – Miles Davis | AllMusic". allmusic.com. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ a b Davis & Troupe 1990, p. 295.

- ^ a b c d e Bitches Brew [1999 Reissue] (Media notes). Columbia Records. 1999. C2K 65774.

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1990, p. 298.

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1990, p. 299.

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1990, p. 301.

- ^ Tingen, Paul (May 2001). "Miles Davis and the Making of Bitches Brew: Sorcerer's Brew". Jazz Times. Retrieved 11 Nov 2014.

- ^ a b c Tingen, Paul. "Miles Davis and the Making of Bitches Brew". JazzTimes. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ^ "Looking Back On 'Bitches Brew': The Year Miles Davis Plugged Jazz In". NPR.org. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ^ Spencer, Neil (4 September 2010). "Miles Davis: The muse who changed him, and the heady Brew that rewrote jazz". The Observer. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ^ "The Making of Bitches Brew". by Paul Tingen and Enrico Merlin. Retrieved 2013-03-25

- ^ a b c Tanner, Paul O. W.; Maurice Gerow; David W. Megill (1988) [1964]. "Crossover — Fusion". Jazz (6th ed.). Dubuque, IA: William C. Brown, College Division. pp. 135–136. ISBN 0-697-03663-4.

- ^ Losin, Peter. "Session Details". Miles Ahead. Retrieved 2007-08-04.

October 26, 1969... 'Bitches Brew'... 'Miles Runs the Voodoo Down'... 'Spanish Key'

- ^ "Miles Davis – Chart History – Billboard 200 – Bitches Brew". Billboard. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ "Miles Davis – Bitches Brew (2018, SACD)". Discogs. 8 August 2018.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (1981). "Miles Davis: Bitches Brew". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the '70s. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306804093. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2011). "Miles Davis". Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th ed.). Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0857125958.

- ^ a b "Miles Davis - Bitches Brew CD Album". CD Universe. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- ^ Holtje, Steve; Lee, Nancy Ann, eds. (1998). "Miles Davis". MusicHound Jazz: The Essential Album Guide. Music Sales Corporation. ISBN 0825672538.

- ^ a b Cook, Richard; Brian Morton (2006) [1992]. "Miles Davis". The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings. The Penguin Guide to Jazz (8th ed.). New York: Penguin. pp. 327. ISBN 0-14-102327-9.

- ^ Richardson, Mark (10 September 2010). "Miles Davis: Bitches Brew [Legacy Edition] Album Review". Pitchfork.

- ^ Considine, J. D. (2004). "Miles Davis". in The Rolling Stone Album Guide: pp. 215, 218.

- ^ Hartwig, Andrew (June 12, 2005). Review: Bitches Brew. Sputnikmusic. Retrieved on 2010-10-08.

- ^ Hull, Tom (n.d.). "Grade List: Miles Davis". Tom Hull – on the Web. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ^ Winner, Langdon (May 28, 1970). Review: Bitches Brew. Rolling Stone. Retrieved on 2010-10-08.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (May 21, 1970). "Jazz Annual". The Village Voice. New York. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (1970). "Jazz & Pop Ballot 1970". Jazz & Pop. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- ^ Segell, Michael (December 28, 1978). "The Children of 'Bitches Brew'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- ^ Hull, Tom (November 30, 2003). "November 2003 Notebook". tomhull.com. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- ^ Rusch, Bob (1994). Ron Wynn (ed.). All Music Guide to Jazz. AllMusic. M. Erlewine, V. Bogdanov (1st ed.). San Francisco: Miller Freeman Books. p. 197. ISBN 0-87930-308-5.

- ^ "1970 Down Beat Critics Poll". downbeat.com. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012. Retrieved November 14, 2008.

- ^ Staff (November 2003). RS500: 94) Bitches Brew Archived 2010-12-07 at the Wayback Machine. Rolling Stone. Retrieved on 2010-10-08.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. 22 September 2020.

- ^ Robert Dimery; Michael Lydon (7 February 2006). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die: Revised and Updated Edition. Universe. ISBN 0-7893-1371-5.

- ^ Snyder, Matt (December 1997). "An Interview with Bobby Previte". 5/4 Magazine. Archived from the original on 2006-01-12. Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- ^ Sutcliffe, Phil (October 1997), "Radiohead: An Interview With Thom Yorke", Q

- ^ Simmons, Ted (February 26, 2013). "Bilal's 25 Favorite Albums". Complex. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ Breithaupt, Don (2007). Steely Dan's Aja. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 25–26. ISBN 9780826427830. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Miles Davis – Bitches Brew" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ^ "Portuguesecharts.com – Miles Davis – Bitches Brew". Hung Medien. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ "Miles Davis Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ^ "Miles Davis Chart History (Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ^ "Miles Davis Chart History (Top Jazz Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved October 3, 2024.

- ^ "British album certifications – Miles Davis – Bitches Brew". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ "American album certifications – Miles Davis – Bitches Brew". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ "Please advise". Letters of Note. Archived from the original on 2012-11-10. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

Sources

- Davis, Miles; Troupe, Quincy (1990). Miles: The Autobiography. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-72582-2.

Further reading

edit- Draper, Jason (2008). A Brief History of Album Covers. London: Flame Tree Publishing. pp. 86–87. ISBN 9781847862112. OCLC 227198538.

External links

edit- Salon Entertainment: a Master at dangerous play

- A history of jazz fusion

- Miles Davis – The Electric Period

- Article by Paul Tingen: Complete Bitches Brew Sessions boxed set at the Miles Beyond site

- Article by Paul Tingen: In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew

- The Sorcerer of Jazz by Adam Shatz, NY Review of Books, September 29, 2016 issue