St Mary Matfelon church, popularly known as St Mary's, Whitechapel, was a Catholic then after the English Reformation a Church of England parish church on Whitechapel Road, Whitechapel, London (in the county of Middlesex until 1889). It is repeatedly supposed by many works and oral histories that the church was covered in a lime whitewash, which gave the chapelry (district) its common name, Whitechapel. Around 1320, it became called St Mary Matfelon. About that time it became a parish in its own right but its priest for many years was a nominee of the Rector of Stepney. The church's earliest known priest was Hugh de Fulbourne in 1329. Last rebuilt in the 19th century, the church was firebombed during the Blitz leading to its demolition in 1952. Its nave's stone footprint and graveyard – its headstones removed – are the basis of Altab Ali Park on the south side of the thoroughfare.[1][2]

| St Mary's, Whitechapel | |

|---|---|

| St Mary Matfelon Church, Whitechapel | |

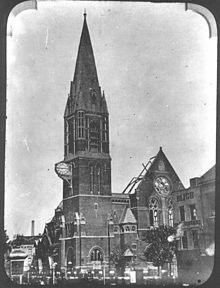

St Mary's Church, Whitechapel, after the fire in 1880 | |

| 51°30′59″N 0°04′07″W / 51.5163°N 0.0686°W | |

| Location | Whitechapel, London |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| History | |

| Status | parish church |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | defunct |

| Completed | 1329 |

| Administration | |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Diocese | London |

| Archdeaconry | Stepney |

| Deanery | Tower Hamlets |

History

editA building going by this name or its aliases stood for at least 670 years until its last form was demolished. For all or most of its time, the place of worship stood where Adler Street meets White Church Lane and Whitechapel High Street. The original form was the white chapel or, more formally, the chapel of St Mary, Stepney.[3] The white chapel stood by 1282 at some distance outside the bars at Aldgate, to which the high street leads.[3] It was created as a chapel-of-ease for a western tranche of that sprawling parish. The building was the nexus by 1320 of its own parish: St Mary Matfelon, Whitechapel, whose vicar and vicarage were reserved as the gift of the rector of Stepney.[3] This was the second-oldest church in Stepney after St Dunstan's, Stepney.

The church's name may have commemorated a founder or benefactor with the surname Matfelon.[4] A wine merchant named Richard Matefelun is recorded in the area in the 13th century.[5]

In 1511, a parishioner, Richard Hunne, after a dispute with the priest over his infant son's funeral, sought to use the English common law courts to challenge the church's authority. In response, church officials arrested him for trial in an ecclesiastical court on the capital charge of heresy. In December 1514, while awaiting trial, Hunne was found dead in his cell, and murder by church officials was suspected.[6]

By 1673, the historic definition of the parish of Stepney was divided into nine separate parishes. The third documented iteration of the church was built on the site largely at the expense of Octavius Coope; it was opened and re-consecrated on 2 February 1877.

In 1797, the body of the sailor Richard Parker, hanged for his leading role in the Nore mutiny, was given a Christian burial at Whitechapel after his wife exhumed it from the unconsecrated burial ground to which it was originally consigned. Crowds gathered to see the body before it was buried.

On 26 August 1880, a fire devastated the church, leaving its thin tower, vestry and church rooms intact. It was rebuilt and opened once more on 1 December 1882, this time with a capacity for 1600 worshippers and including an external pulpit for sermons, some of which were given in Yiddish.[7]

Monkton Combe School near Bath, Somerset maintained a strong evangelical missionary relationship with this church, beginning in 1906 under the auspices of the then Rector, Rev. A. M. Robinson, an Old Monktonian. Old boys served as curates and ran the Boys' Club and the Men's Bible Classes. The school sent regular financial donations and other support to what they called the "Whitechapel Mission".[8] The school's Monktonian Magazine of February 1911 has an article "An OM at Work" describing the church, its congregation, and mission in detail.[9] It describes the school as "a kind of fairy godmother" to the boys.[9] In 1920 the mission transferred to St Luke's, Hackney.[10]

During the Blitz, on 29 December 1940, a Luftwaffe fire raid destroyed the church. It was left in disrepair until it was demolished in 1952.

The site of the church became St Mary's Gardens in 1966; it is now a public park called Altab Ali Park; an outline of the footprint of the church is all that remains of it. Among those buried on the site are the mutineer Richard Parker, the hangman Richard Brandon, the philanthropist Sir John Cass, and "Sir" Jeffrey Dunstan, the "Mayor of Garratt". The clockmaker Ahasuerus Fromanteel was buried at the church in 1693. The wildlife artist Marmaduke Cradock was buried there in 1717.

The 'White Chapel'

editWhitewash made of lime and chalk was used as paint on the outside of the original church in the Middle Ages, and gave it a bright white finish. It is commonly believed that this prompted locals to call it the 'white chapel'. The church's prominent position on the westerly junction of Whitechapel Road made it a landmark and it became the name of the area.

Architecture

editThe "thoroughly repaired" late Stuart church (before its 1877 complete rebuilding) and some of its history are described in a book of 1829:

This church is of some antiquity, as appears by Hugh de Fulbourn being rector thereof in the year 1329. It was originally a chapel of ease to the church of St Dunstan, Stepney, and is supposed to have obtained the epithet of White from having been white-washed or plastered on the outside.

The first church erected on the spot after it ceased to be a chapel of ease of Stepney parish, was dedicated to St Mary Matfelon; a name which has given birth to many conjectures respecting its signification, but which is probably derived from the Hebrew word Matfel, which signifies both a woman lately delivered of a son, and a woman carrying her infant son; either of which significations is applicable to the Virgin Mary and her holy babe.

The old church being in a very ruinous condition, it was taken down in 1673, and the present edifice was soon after erected in its stead. This is a coarse and very irregular building; the body, which is formed of brick, and ornamented with stone rustic work at the corners, is ninety-three feet in length, sixty-three feet in breadth; and the height of the tower and turret is eighty feet. The principal door is ornamented with a kind of rustic pilasters, with cherubs’ heads by way of capitals, and a pediment above. The body is enlightened with a great number of windows, which are of various forms, and different sizes, a sort of Venetian, oval and square. The square windows have ill-proportioned circular pediments; and the oval, or more properly elliptic windows, some of which stand upright and others cross-ways, are surrounded with thick festoons. The steeple, which is of stone, rises above the principal door, and is crowned with a plain square battlement. It was sometime since thoroughly repaired.[11]

Libellous altarpiece 1713

editRichard Welton was admitted rector of St Mary's on 30 June 1697.[12] Welton had strong Jacobite sympathies, and regarded the Whig clergymen as apostates.[12] About the close of 1713 he had a new altarpiece placed in the church, representing the Last Supper.[12] The painter, James Fellowes, was instructed to portray Bishop Burnet in the semblance of Judas, but, fearing the consequences, he obtained permission to substitute Dean White Kennett with the words "The Dean the Traitor" underneath.[12] The apostle John, depicted as a mere boy, was considered singularly like Prince James Edward, and Christ himself was identified by some with Henry Sacheverell.[12] Crowds flocked to see the altarpiece, among them Mrs Kennett, who recognised her husband with indignant astonishment.[12] Kennett took proceedings in the court of the bishop of London, John Robinson, and on 26 April 1714 obtained an order for its removal.[12][13]

Upon the death of the last Stuart monarch, Queen Anne, Welton refused to take the oath of allegiance to the new Hanoverian king George I in October 1714. He was therefore deprived of his offices on 3 March 1715.[14]

Description of a Sunday service at St Mary's 1896

editThe following description of a Sunday service appeared in East London Sketches of Christian Work and Workers by Henry Walker, published by the Religious Tract Society in 1896:

The church of St Mary Matfelon - to give it the old historic name - is itself a message of beauty and graciousness in such a quarter. Its noble spire rises two hundred feet in height, far above the houses of the populous and struggling district around, a striking and commanding feature visible far and wide. The beautifully-toned bells are filling the air with their inviting peal. Through the crowded streets of loungers, well-to-do church-goers of the middle classes are wending their way to morning service. We enter with them, and find ourselves in a large, spacious, impressive, and richly-decorated building. The church, it should be said, is the grateful and lavish gift of a former parishioner: the lofty roof, richly-coloured walls, and the sculptures and stained-glass windows betoken alike the costliness of the offering and the giver's conception of a great church for East London. As St Mary's, Whitechapel, is one of the foremost in popularity and equipment for parish work, and one of the best attended of the great East End churches, everything that may account for its reputation will well deserve attention.

The church seats thirteen hundred people. The services are fully choral; the Psalms are chanted both morning and evening, the congregation being led by the surpliced choir. The musical service, though keeping pace with the increasing capacities of present-day congregations, is always well within congregational lines. The growing delight in singing as an act of common worship which now characterises all Christian denominations, and which is a great feature of all East London places of worship is indeed amply provided for at St Mary's, and that, too, in a way which shows how Evangelicalism is able without compromise to take full share of the latitude which is now so commonly assigned to congregational utterance in church.

Sunday evening at St Mary's is a still larger and more notable demonstration of church-going, and the scene is one of the most encouraging sights which East London can show. The church is filled with at least a thousand persons of the working and poorer classes of Whitechapel. The beautiful and impressive service is an experience not to be forgotten. The sermon, too, is redolent of the place and the people. In the evening the vicar applies himself to the actual circumstances and difficulties of the congregation he knows so well. Here it may be mentioned that the population of the parish is twenty thousand, and that every family of this large number, Jew and Gentile alike, is regularly visited by the rector and his assistant clergy. Mr. Sanders can accordingly put his hand at once on the ills amidst which his people live.

Mr. Sanders' picture of the underpaid industries of Whitechapel and the results in bodies and souls of the unfortunate workers contributes important data for a view of the problem from the Christian standpoint, and seldom have the responsibilities of society in this matter been stated with greater power and wiser sympathy. ...

Sunday afternoon is also an occasion for meetings in church for closer dealings with the industrial classes. The Pleasant Sunday Afternoon movement, in its higher aspects, has been commenced with much success. A gospel address from one of the clergy, the services of an excellent orchestra, reinforced by the fine organ of the church, with popular hymns and sacred solos, attract a class who seldom otherwise see the interior of a beautiful church, or hear sacred music in which they can join, or get into close personal touch with the clergy. The imprimatur which the rector of such a parish has freely given to this new development of the Sunday afternoon service is naturally felt in East London to be a great encouragement. Certainly in no part of London could crowded streets give a better mandate for these social gatherings as conducted at St Mary's.[15]

Notable people

editThomas Lord Busby, a portrait artist and engraver, was baptised at St Mary’s in 1782.[16]

References

edit- ^ Ben Weinreb and Christopher Hibbert (eds) (1983) "Whitechapel" in The London Encyclopaedia: 955-6

- ^ Andrew Davies (1990) The East End Nobody Knows: 15–16

- ^ a b c Baker, T. F. T., ed. (1998). "Stepney: Churches". A History of the County of Middlesex. Vol. 11. London: Victoria County History. pp. 70–81.

- ^ Mills, A. D. (2010). "Whitechapel". A Dictionary of London Place-Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191726743.

- ^ "The Church of St Mary Matfelon, Whitechapel: part one | UCL The Survey of London". blogs.ucl.ac.uk.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ "An Open Air Service in Yiddish, St Mary's Whitechapel". Jewish Museum London. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ Monkton Combe School archives

- ^ a b Monktonian Magazine, February 1911, pp 187-189

- ^ Monktonian Magazine, December 1920

- ^ James Elmes, James; Thomas Shepherd, Thomas Hosmer (1829). London and its Environs in the Nineteenth Century. London: Jones & Co. p. 107.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bennett, GV (1957). White Kennett. 1660–1728. Bishop of Peterborough. London: SPCK. pp. 127–130.

- ^ "A Representation of the Altar-piece lately set up in White-Chappel Church". The British Museum.

- ^ Cornwall, Robert D (1885–1900). . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 2004, index no. 101029031

- ^ Walker, Henry. "II. Whitechapel". East London. I: Whitechapel. Religious Tract Society.

- ^ Register of Baptisms, St Mary’s, Whitechapel, Thomas Lord Busbey, 10 November 1782, ancestry.co.uk, accessed 30 July 2021 (subscription required)