Metrotown is a town centre serving the southwest quadrant of Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada. It is one of the city's four officially designated town centres,[3] as well as one of Metro Vancouver's regional town centres.[4] It is the central business district of the City of Burnaby.[5]

Metrotown | |

|---|---|

Metrotown skyline as seen from Richmond, British Columbia | |

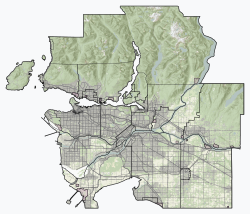

Location of Metrotown within Metro Vancouver | |

| Coordinates: 49°13′32″N 123°00′12″W / 49.2255°N 123.0032°W | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| Region | Lower Mainland |

| Regional District | Metro Vancouver |

| City | Burnaby |

| Quadrant | Southwest |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Mike Hurley |

| • MP (Fed.) | Jagmeet Singh (NDP) |

| • MLA (Prov.) | Anne Kang (NDP) |

| Area | |

| • Land | 2.97 km2 (1.15 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• Total | 24,889 |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| Area codes | 604, 778, 236, 672 |

As officially defined by the City of Burnaby, the town centre is bounded on the west by Boundary Road (taking in Central Park), on the south by Imperial Street, on the east by Royal Oak Avenue, and on the north by a series of local streets (Thurston, Bond, Grange and Dover streets),[6] giving an area of 2.97 km2 (730 acres).[1][7] Kingsway forms the central commercial spine for the neighbourhood, and is paralleled to the south by the SkyTrain tracks running alongside Central Boulevard.

The area is served by Patterson and Metrotown SkyTrain stations, while Royal Oak station sits just beyond the southeastern limits of the district. The area is characterised by its many high rise commercial and residential buildings.

Name origin

editUrban researcher and economist R. W. Archer credited the Baltimore Regional Planning Council (BRPC) for coining the term "metrotown" in 1962.[8] The BRPC envisioned metrotowns as "cohesive urban developments... deployed radially and in a series of rings around the City of Baltimore", each accommodating 100,000 to 200,000 people and at greater densities than what was then common in suburban areas.[9][10]

Archer adapted the term in his two-part article From New Towns to Metrotowns and Regional Cities, which appeared in the July 1969 issue of The American Journal of Economics and Sociology,[11] to refer to "a unit for planned metropolitan development" consisting of a wide variety of land uses and offering "a large measure of local employment and city-type services", but still "significantly interdependent with the rest of the metropolis".[12] He further suggested that building a connected series of metrotowns was the most cost-effective manner for establishing new urban settlements,[11] and saw developments around Stockholm like Vällingby and Högdalen as examples of this type of built form.[13]

The term was subsequently adopted by the municipality of Burnaby in the 1970s, initially as a common noun to refer to a type of urban development; it eventually became a proper noun referring exclusively to the area around the intersection of Kingsway and Sussex Avenue.

History

editSettlement and industry

editOn the recommendation of Colonel Richard Moody, the Royal Engineers constructed a trail linking colonial capital New Westminster and False Creek to facilitate troop movement between the two points.[14][15] The trail (which later became Kingsway) opened in 1860, and cut diagonally across Burrard Peninsula;[14] land was set aside as a military reserve at a plateau along the road in the area of modern-day Metrotown.[14][15] The road was improved following Burnaby's municipal incorporation in 1892, and the parallel Central Park interurban line connecting Vancouver and New Westminster opened the previous year, making the area increasingly favourable for settlement.[14] Consequently, the provincial government established a series of holding lots out of the military reserve in the 1890s to accommodate working class residents.[14][15] The lots were drawn at right angles to the interurban line, which ran from the northwest to the southeast, accounting for Metrotown's street orientation.[15]

During the Great Depression, Burnaby reeve William Pritchard instituted a series of make-work programs to put the unemployed to work, using municipal funds and loans.[15] This put a strain on Burnaby's finances, and in 1932 the province stepped in by suspending the functions of Burnaby's government and appointing a commissioner to run municipal affairs.[15][16] Under the province's control, Burnaby struck a deal with the Ford Motor Company to build an assembly plant near Kingsway and McKay Avenue.[17] The plant opened in 1938, and was used to produce military vehicles during World War II;[17] it became an Electrolier facility at some point after the war.[18] Wholesale grocer Kelly-Douglas Company built a manufacturing plant and warehouse to the east of the Ford/Electrolier plant in 1946, and Simpsons-Sears opened a catalogue sales and distribution facility to the east of the Kelly-Douglas plant in 1954.[17]

Passenger service on the stretch of the Central Park interurban line through Burnaby and New Westminster ceased operations on October 23, 1953.[19]

Planning for a "metro town"

editBuilding upon a 1964 report by the Lower Mainland Regional Planning Board (forerunner to the Greater Vancouver Regional District, GVRD), Burnaby's planning department prepared a report titled Apartment Study, which was approved by the municipal council in 1966.[20] In this document, Burnaby's planners proposed a hierarchical structure for co-locating housing, commercial activity and other amenities, with a "town centre" level as the highest tier.[21] The town centres were to serve as "a major focus of population and community activity", include "a complete cross section of commercial facilities" and "a full range of cultural and recreational activity", and provide residential accommodation "with easy access to well developed industrial areas and places of employment".[21][22] The planners further identified three sites around the municipality as candidates to be developed into town centres: Brentwood, Lougheed and the area around the Simpsons-Sears facility at Kingsway and Sussex Avenue.[21]

Burnaby's planning department further conducted a survey of the local land-use structure, and published a hardcover book titled Urban Structure in 1971. Echoing Archer's metrotown concept, the book recommended establishing an "intermittent grid of metro towns" as the best alternative out of the various urban built forms.[23][24] However, by 1974, the planners decided instead to create only one metro town, for fear that having multiple such developments (as recommended by Urban Structure) would divide the municipality's focus and drain its resources.[25] Brentwood, Lougheed and the Simpsons-Sears site were evaluated as candidates for the site of the sole metro town; with the former two locations already gravitating towards a car-centric pattern of development, the planners decided that the Simpsons-Sears site had the most potential to match their original vision for a metro town.[25] The report thus recommended that "the Kingsway/Sussex town centre be designated as a Metrotown development area"; the recommendation was approved by the municipal council in July 1974.[26]

Concurrent with planning at the municipal level, the GVRD also worked on addressing growth patterns at the regional level, and in 1975 released The Livable Region 1976/1986, which proposed establishing "regional town centres" (RTCs) in several locations around Greater Vancouver. Such centres were envisioned as nodes of employment, entertainment and cultural amenities serving the local population, in order to reduce travel into the city of Vancouver.[27] Burnaby's central location within the metropolitan area was seen as an advantage to siting an RTC in the municipality,[28] and with the planning process for the Metrotown development at Kingsway/Sussex already under way, the GVRD expected that designating Metrotown as an RTC would provide for the easiest implementation of the concept and set an example for future RTCs to be established in Surrey and Coquitlam.[29][30] The site's location along the disused Central Park interurban was also considered favourable, as the GVRD was proposing to build a light rail transit system (which eventually became the SkyTrain) along that right of way.[31] The proposal thus recommended for an RTC to be "started immediately in the Central Park area of Burnaby" (as well as in downtown New Westminster).[30]

Burnaby and the GVRD subsequently launched a joint study of the Metrotown RTC,[28] and the municipality's planning department followed up in 1977 with the release of Metrotown's development plan, which further articulated the development concept and strategy for the area.[26][32]

Uncertainty emerges

editRecessions in the 1970s and early 1980s, along with an altered political landscape following the 1979 municipal election, cast uncertainties onto the Metrotown development,[32][33] with mayor Dave Mercier suggesting in 1981 that the Metrotown plans be revisited.[34] Meanwhile, with "Metrotown" being perceived by local residents as a "sterile name" unindicative of its environs, a naming contest was held in 1982 to rename the Kingsway/Sussex area.[35] "Orchard Park" was the leading candidate until the contest was called off by mayor Bill Lewarne, citing the expense associated with updating the literature already printed which promoted the area as Metrotown.[35]

By that point, Daon Development Corporation had emerged as the main developer for the Kelly-Douglas site at Metrotown, with proposals to build a department store complex, offices and residential towers.[36][37] However, the recessionary environment and the company's financial woes continued to stall development.[36] Further complicating matters was a proposal by Triple Five Group (developers of West Edmonton Mall and Mall of America) to build a large mall and amusement centre at the corner of Lougheed Highway and Boundary Road.[38] Fearing this proposal would deflect activity away from Metrotown, municipal council reaffirmed in 1984 that Metrotown would remain as Burnaby's commercial core,[38] and mayor Lewarne stated that council would not rezone the Lougheed/Boundary site for the Triple Five proposal.[39] With the provincial government refusing to intervene,[40] the Triple Five proposal was abandoned. Nonetheless, while that proposal was in play, the Metrotown development experienced delays in locating anchor tenants, further worsening Daon's finances.[39] Daon pulled out of the development in 1985 before ceasing operations the next year; the Kelly-Douglas site was subsequently acquired by Cambridge Shopping Centres (now Ivanhoe Cambridge).[41]

Development resumes

editDevelopment in Metrotown began to pick up in the mid-1980s, in tandem with the launch in late 1985 of the SkyTrain system (including Metrotown Station), which follows the alignment of the former interurban through the area. The form of development, however, came to be dominated by retail complexes, differing markedly from the original vision for Metrotown as a pedestrian-oriented mixed-use node.[42]

Cal Investments received financial backing from Manulife Financial to develop the Simpsons-Sears site,[43] with ground breaking in August 1985 and completion targeted for fall 1986;[44] Sears was to remain as an anchor tenant at the new Metrotown Centre, to be joined in that role by Woodward's.[44]

The Electrolier site became Station Square, opened in 1988 by Wesbild Enterprises. On opening day in 1988, part of anchor tenant Save-On-Foods' rooftop parking deck collapsed, injuring 21 people but causing no deaths.[45] The strip mall closed in 2012 to go through redevelopment. Also called Station Square, it has five condominium towers that were all completed in August 2022.[46]

Cambridge developed the Kelly-Douglas site into Eaton Centre (named after its anchor), which opened in 1989;[47] the mall was renamed Metropolis following the demise of the Eaton's chain in 1999.

The Crystal Mall complex opened at Kingsway and Willingdon Avenue between 1999 and 2000,[48] incorporating an Asian-themed shopping centre, residential and commercial highrises, and a Hilton hotel. Ivanhoe Cambridge purchased Metrotown Centre in 2002,[15][49] which was merged with Metropolis into a single mall (Metropolis at Metrotown) in 2005,[50] creating the third largest enclosed shopping mall in Canada by total retail floor space.[4][51]

Features and amenities

editCentral Park sits at the western edge of Metrotown, and includes amenities such as tennis courts, an outdoor swimming pool, a pitch-and-putt golf course, and Swangard Stadium at its northwestern corner.[52] Smaller parks in the area include Kinnee Park, Maywood Park and Old Orchard Park. The area is also served by the Bonsor Recreation Complex[53] and the Burnaby Public Library's Bob Prittie Metrotown branch.[54]

Marlborough Elementary School and Maywood Community School (K-7) both fall within Metrotown's borders, while Chaffey-Burke Elementary sits just to the north. The closest secondary schools serving Metrotown are Moscrop Secondary School at Willingdon Avenue and Moscrop Street, and Burnaby South Secondary School near Royal Oak Avenue and Rumble Street. All aforementioned schools are operated by the Burnaby School District.

The town centre is also home to Old Orchard Shopping Centre, a strip mall at the intersection of Kingsway and Willingdon Avenue which pre-dates the malls along the south side of Kingsway built since the 1980s.

Demographics

editPopulation

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 24,518 | — |

| 2006 | 25,540 | +4.2% |

| 2011 | 27,970 | +9.5% |

| 2016 | 29,009 | +3.7% |

| Source: Statistics Canada[55] | ||

As of 2006, Metrotown had a population of 25,540, increasing by 4% from 2001.[56] Between 1991 and 2001, the town centre's population increased by 43.9%.[57] Jobs in the town centre numbered around 22,900 in 2006, accounting for 20% of employment in Burnaby.[58]

According to the 2006 census, 53% of the residents in the census tract immediately south of the Metrotown SkyTrain station commuted to work by public transit, the highest of any census tracts in Metro Vancouver;[59] public transit mode share to work for the entire Metrotown area was around 42%.[60]

Ethnicity

edit| Ethnic group | Population | % |

|---|---|---|

| East Asian | 13,760 | 47.6% |

| European | 7,720 | 26.7% |

| Southeast Asian | 2,695 | 9.3% |

| South Asian | 1,805 | 6.2% |

| Middle Eastern | 1,220 | 4.2% |

| Latin American | 615 | 2.1% |

| Aboriginal | 395 | 1.4% |

| Black | 390 | 1.3% |

| Other | 625 | 2.2% |

| Total population | 29,009 | 100% |

Language

edit| Language | % |

|---|---|

| English | 30.5% |

| Mandarin | 25.3% |

| Cantonese | 11% |

| Tagalog | 4.6% |

| Korean | 4.3% |

| Russian | 2.7% |

| Persian | 2.6% |

| Spanish | 2.3% |

| Punjabi | 2.1% |

| Hindi | 1.8% |

| Serbian | 1.7% |

| Arabic | 1.6% |

| Portuguese | 1.2% |

| Other | 9.2% |

| Total % | 100% |

References

edit- Footnotes

- ^ a b Burnaby Planning Department 1977, p. 14.

- ^ "Metrotown Highlights" (PDF). City of Burnaby. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 20, 2017. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- ^ "Town Centres". City of Burnaby. Archived from the original on 2021-02-17. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- ^ a b "Metrotown City Centre". Metro Vancouver. Archived from the original on 2013-01-06. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- ^ "Metrotown Downtown Plan". City of Burnaby. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ Perkins 1992, p. 159.

- ^ "Metrotown General Land Use Map" (PDF). City of Burnaby. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-10-13. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- ^ Pereira 2011, p. 15.

- ^ Baltimore Regional Planning Council; Maryland State Planning Department (1962). Metrotowns for the Baltimore Region: A pattern emerges (Report). pp. 2–3.

- ^ O'Bryan, Deric; McAvoy, Russell L. (1966). Gunpowder Falls Maryland: Uses of a water resource today and tomorrow. U.S. Geological Survey. p. 64.

- ^ a b Pereira 2011, p. 14.

- ^ R. W. Archer (1969). "From New Towns to Metrotowns and Regional Cities, I". The American Journal of Economics and Sociology. 28 (3): 257–269. doi:10.1111/j.1536-7150.1969.tb03223.x.

- ^ R. W. Archer (1969). "From New Towns to Metrotowns and Regional Cities, II". The American Journal of Economics and Sociology. 28 (3): 385–398. doi:10.1111/j.1536-7150.1969.tb03104.x.

- ^ a b c d e Beasley 1976, pp. 106–107.

- ^ a b c d e f g Glavin, Terry (2006). "Lost Cities". Vancouver Review. Archived from the original on 2013-04-11. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- ^ "Young Burnaby: 1911-1943" (PDF). City of Burnaby. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-09-21. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- ^ a b c "Burna-Boom 1925 - 1954". Heritage Burnaby. Archived from the original on 2012-10-11. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- ^ Burnaby Planning Department 1977, p. 18.

- ^ Ewert, Henry (January–February 2010). "British Columbia Electric Railway Company Limited" (PDF). Canadian Rail (534): 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-22. Retrieved 2013-01-01.

- ^ Pereira 2011, p. 34.

- ^ a b c Pereira 2011, p. 35.

- ^ Parr, A.L.; Burnaby Planning Department (1966). Apartment Study (Report). pp. 2–3.

- ^ Pereira 2011, p. 45.

- ^ Beasley 1976, pp. 35–37.

- ^ a b Pereira, David. "The Town Centre Model: Part 3". Retrieved 2012-12-25.

- ^ a b Burnaby Planning Department 1977, p. 7.

- ^ Greater Vancouver Regional District 1975, p. 18.

- ^ a b Greater Vancouver Regional District 1975, p. 32.

- ^ Perkins 1992, p. 48.

- ^ a b Greater Vancouver Regional District 1975, p. 20.

- ^ Greater Vancouver Regional District 1975, p. 20–21, 24.

- ^ a b Pereira, David. "Metrotown". Retrieved 2012-12-25.

- ^ Pereira 2011, pp. 88–91.

- ^ Mackey, Lloyd (1981-09-16). "Burnaview". Burnaby Today.

- ^ a b "Metrotown name stays". Burnaby Today. 1982-10-20.

- ^ a b "No early awakening for Metrotown". Burnaby Today. 1982-09-08.

- ^ "Daon plans huge project". Burnaby Now. 1983-12-12.

- ^ a b "Backroom deal favors mall; Political involvement slammed". Burnaby Now. 1985-02-04.

- ^ a b "Kiss Metrotown Goodbye?". Burnaby Now. 1985-02-25.

- ^ "Victoria 'out' of mall brawl". Burnaby Now. 1985-02-11.

- ^ "Daon out of Metrotown". Burnaby Now. 1985-10-16.

- ^ Pereira 2011, p. 91.

- ^ "Metrotown makes it big". Burnaby Now. 1985-04-01.

- ^ a b "Bulldozers mark Metrotown's start". Burnaby Now. 1985-09-02.

- ^ Feld, Jacob; Carper, Kenneth L. (1996). Construction Failure. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 193–194. ISBN 9780471574774.

- ^ Chan, Kenneth (September 26, 2022). "That time Save-On-Foods Metrotown collapsed during its grand opening". Daily Hive. Burnaby, B.C. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ Constantineau, Bruce (1987-02-25). "Developers take Burnaby to court". The Vancouver Sun.

- ^ "About Us". The Crystal Mall. Archived from the original on 2013-01-03. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

- ^ "Ivanhoe Canmbridge Purchases Metrotown Centre". Lexpert Magazine. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

- ^ 2005 Report on Activities (PDF) (Report). Ivanhoe Cambridge. 2005. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

- ^ "Burnaby Visitor's Guide" (PDF). City of Burnaby. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

- ^ "Central Park". City of Burnaby. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ^ "Bonsor Recreation Complex". City of Burnaby. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ^ "Bob Prittie Metrotown: Burnaby Public Library". Burnaby Public Library. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ^ "Census Tract Reference Maps, by Census Metropolitan Areas or Census Agglomerations" (PDF).

- ^ 2006 Census Bulletin #1: Population and Dwelling Counts (PDF) (Report). Greater Vancouver Regional District. March 2007. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-03-31. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

- ^ GVRD Policy and Planning Department (2002). 2002 Annual Report: Livable Region Strategic Plan (PDF) (Report). Greater Vancouver Regional District. p. 19. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

{{cite report}}:|author=has generic name (help)[permanent dead link] - ^ Tate 2009, p. 15.

- ^ Skelton, Chad (2012-03-01). "Metrotown the most transit-friendly neighbourhood in the region". The Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

- ^ Pereira 2011, pp. 75, 144.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2017-02-08). "Census Profile, 2016 Census - 9330227.02 [Census tract], British Columbia and Vancouver [Census metropolitan area], British Columbia". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2022-09-16.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2017-02-08). "Census Profile, 2016 Census - 9330228.03 [Census tract], British Columbia and Vancouver [Census metropolitan area], British Columbia". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2022-09-16.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2017-02-08). "Census Profile, 2016 Census - 9330226.03 [Census tract], British Columbia and Vancouver [Census metropolitan area], British Columbia". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2022-09-16.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2017-02-08). "Census Profile, 2016 Census - 9330227.01 [Census tract], British Columbia and Vancouver [Census metropolitan area], British Columbia". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2022-09-16.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2017-02-08). "Census Profile, 2016 Census - 9330226.04 [Census tract], British Columbia and Vancouver [Census metropolitan area], British Columbia". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2022-09-16.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2017-02-08). "Census Profile, 2016 Census - 9330228.02 [Census tract], British Columbia and Vancouver [Census metropolitan area], British Columbia". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2022-09-16.

- Bibliography

- Beasley, Larry (1976). A design probe comparison of regional and municipal attitudes toward regional town centres: Case study in Burnaby, B.C. (M.A. thesis). University of British Columbia. Retrieved 2012-12-23.

- Burnaby Planning Department; Norman Hotson Architects (June 1977). Burnaby Metrotown: a development plan (PDF) (Report). City of Burnaby. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-02-17. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- Greater Vancouver Regional District (1975-03-26). The Livable Region 1976/1986 (Report).

- Pereira, David (2011). The intersection of town centre planning and politics: Alternative development in an inner suburban municipality in the Metro Vancouver region (M.Urb. thesis). Simon Fraser University. Archived from the original on 2013-02-19. Retrieved 2012-12-23.

- Perkins, Ralph A. (1992). Greater Vancouver regional town centres policy in comparative perspective (M.A. (Planning) thesis). University of British Columbia. Retrieved 2013-01-01.

- Tate, Laura Ellen (2009). Communicative regionalism and metropolitan growth management outcomes: A case study of three employment nodes in Burnaby - an inner suburb of Greater Vancouver (M.A. (Planning) thesis). University of British Columbia. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

External links

edit- Metro Vancouver: Metrotown City Centre

- DavidPereira.ca: Metrotown — History of Metrotown's development