The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court is the treaty that established the International Criminal Court (ICC).[5] It was adopted at a diplomatic conference in Rome, Italy on 17 July 1998[6][7] and it entered into force on 1 July 2002.[2] As of October 2024, 125 states are party to the statute.[8] Among other things, it establishes court function, jurisdiction and structure.

| Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court | |

|---|---|

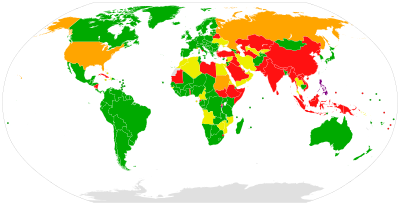

Parties and signatories of the Statute

State party

Signatory that has not ratified

State party that subsequently withdrew its membership

Signatory that subsequently withdrew its signature

Non-party, non-signatory | |

| Drafted | 17 July 1998 |

| Signed | 17 July 1998[1] |

| Location | Rome, Italy[1] |

| Effective | 1 July 2002[2] |

| Condition | 60 ratifications[3] |

| Signatories | 137[2] |

| Parties | 125[2] |

| Depositary | UN Secretary-General[1] |

| Languages | Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish[4] |

| Full text | |

| https://www.un.org/law/icc/index.html | |

The Rome Statute established four core international crimes: genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression. Those crimes "shall not be subject to any statute of limitations".[9] Under the Rome Statute, the ICC can only investigate and prosecute the four core international crimes in situations where states are "unable" or "unwilling" to do so themselves.[10] The jurisdiction of the court is complementary to jurisdictions of domestic courts. The court has jurisdiction over crimes only if they are committed in the territory of a state party or if they are committed by a national of a state party. An exception to this rule is that the ICC may also have jurisdiction over crimes if its jurisdiction is authorized by the United Nations Security Council.

Purpose

editThe Rome Statute established four core international crimes: (I) Genocide, (II) Crimes against humanity, (III) War crimes, and (IV) Crime of aggression. Following years of negotiation, aimed at establishing a permanent international tribunal to prosecute individuals accused of genocide and other serious international crimes, such as crimes against humanity, war crimes and crimes of aggression, the United Nations General Assembly convened a five-week diplomatic conference in Rome in June 1998 "to finalize and adopt a convention on the establishment of an international criminal court".[11][12]

History

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2020) |

Background

editThe Rome Statute is the result of multiple attempts for the creation of a supranational and international tribunal. At the end of the 19th century, the international community took the first steps toward the institution of permanent courts with supranational jurisdiction. With the Hague International Peace Conferences of 1899 and 1907, representatives of the most powerful nations made an attempt to harmonize laws of war and to limit the use of technologically advanced weapons.

After the Nuremberg trials of Nazi leaders, international institutions began prosecuting individuals responsible for crimes against humanity which are inhumane actions that may be legal in a given nation, but represent gross human rights violations. In order to re-affirm basic principles of democratic civilisation, the accused received a regular trial, the right to defense and the presumption of innocence. The Nuremberg trials marked a crucial moment in legal history, and after that, some treaties that led to the drafting of the Rome Statute were signed.[citation needed]

UN General Assembly Resolution n. 260 9 December 1948, the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, was the first step toward the establishment of an international permanent criminal tribunal with jurisdiction on crimes yet to be defined in international treaties. In the resolution there was a hope for an effort from the Legal U.N. commission in that direction.

The U.N. General Assembly, after the considerations expressed from the commission, established a committee to draft a statute and study the related legal issues. In 1951 a first draft was presented; a second draft followed in 1955 but there were a number of delays, officially due to the difficulties in the definition of the crime of aggression, that were only solved with diplomatic assemblies in the years following the statute's coming into force. The geopolitical tensions of the Cold War also contributed to the delays.

In December 1989, Trinidad and Tobago asked the General Assembly to re-open the talks for the establishment of an international criminal court and in 1994 presented a draft statute. The General Assembly created an ad hoc committee for the International Criminal Court and, after hearing the conclusions, a Preparatory Committee that worked on the draft for two years from 1996 to 1998.

Meanwhile, the United Nations created the ad hoc tribunals for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and for Rwanda (ICTR) using statutes—and amendments due to issues raised during pre-trial or trial stages of the proceedings—that are quite similar to the Rome Statute.

The UN’s International Law Commission (ILC) considered the inclusion of the crime of ecocide to be included within the Draft Code of Crimes Against the Peace and Security of Mankind, the document which later became the Rome Statute. Article 26 (crime against the environment) was publicly supported by 19 countries in the Legal Committee but was removed due to opposition from the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the United States of America.[13][14][15]

Establishment

editDuring its 52nd session, the UN General Assembly decided to convene a diplomatic conference "to finalize and adopt a convention on the establishment of an international criminal court".[11][12] The conference was convened in Rome from 15 June to 17 July 1998. It was attended by representatives from 161 member states, along with observers from various other organizations, intergovernmental organizations and agencies, and non-governmental organizations (including many human rights groups) and was held at the headquarters of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, located about 4 km away from the Vatican (one of the states represented).[16][17] On 17 July 1998, the Rome Statute was adopted by a vote of 120 to 7, with 21 countries abstaining.[6]

By agreement, there was no official record of each delegation's vote regarding the adoption of the Rome Statute. Therefore, there is some dispute over the identity of the seven countries that voted against the treaty.[18]

It is certain that the People's Republic of China, Israel, and the United States were three of the seven because they have publicly confirmed their negative votes. India, Indonesia, Iraq, Libya, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, and Yemen have been identified by various observers and commentators as possible sources for the other four negative votes, with Iraq, Libya, Qatar, and Yemen being the four most commonly identified.[18]

Explanations of Vote was publicly declared by India, Uruguay, Mauritius, Philippines, Norway, Belgium, United States, Brazil, Israel, Sri Lanka, China, Turkey, Singapore, and the United Kingdom.[19]

On 11 April 2002, ten countries ratified the statute at the same time at a special ceremony held at the United Nations headquarters in New York City,[20] bringing the total number of signatories to sixty, which was the minimum number required to bring the statute into force, as defined in Article 126.[3] The treaty entered into force on 1 July 2002;[20] the ICC can only prosecute crimes committed on or after that date.[21]

The states parties held a Review Conference in Kampala, Uganda from 31 May to 11 June 2010.[22] The Review Conference adopted a definition of the crime of aggression, thereby allowing the ICC to exercise jurisdiction over the crime for the first time. It also adopted an expansion of the list of war crimes.[23] Amendments to the statute were proposed to implement these changes.

Ratification status

editAs of October 2024[update], 125 states[a] are parties to the Statute of the Court, including all the countries of South America, nearly all of Europe, most of Oceania and roughly half of Africa.[2][24] Burundi and the Philippines were member states, but later withdrew effective 27 October 2017[25] and 17 March 2019,[26] respectively.[2][24] A further 29 countries[a] have signed but not ratified the Rome Statute.[2][24] The law of treaties obliges these states to refrain from "acts which would defeat the object and purpose" of the treaty until they declare they do not intend to become a party to the treaty.[27] Four signatory states—Israel in 2002,[28] the United States on 6 May 2002,[29][30] Sudan on 26 August 2008,[31] and Russia on 30 November 2016[32]—have informed the UN Secretary General that they no longer intend to become states parties and, as such, have no legal obligations arising from their signature of the Statute.[2][24]

Forty-one additional states[a] have neither signed nor acceded to the Rome Statute. Some of them, including China and India, are critical of the Court.[33][34]

Jurisdiction, structure and amendment

editThe Rome Statute outlines the ICC's structure and areas of jurisdiction. The ICC can prosecute individuals (but not states or organizations) for four kinds of crimes: genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression. These crimes are detailed in Articles 6, 7, 8, and 8 bis of the Rome Statute, respectively. They must have been committed after 1 July 2002, when the Rome Statute came into effect.

The ICC has jurisdiction over these crimes in three cases: first, if they took place on the territory of a State Party; second, if they were committed by a national of a State Party; or third, if the crimes were referred to the Prosecutor by the UN Security Council. The ICC may begin an investigation before issuing a warrant if the crimes were referred by the UN Security Council or if a State Party requests an investigation. Otherwise, the Prosecutor must seek authorization from a Pre-Trial Chamber of three judges to begin an investigation proprio motu (on its own initiative). The only type of immunity the ICC recognizes is that it cannot prosecute those under 18 when the crime was committed. In particular, no officials – not even a head of state – are immune from prosecution.

The Rome Statute established three bodies: the ICC itself, the Assembly of States Parties (ASP), and the Trust Fund for Victims. The ASP has two subsidiary bodies. These are the Permanent Secretariat, established in 2003, and an elected Bureau which includes a president and vice-president. The ICC itself has four organs: the Presidency (with mostly administrative responsibilities); the Divisions (the Pre-Trial, Trial, and Appeals judges); the Office of the Prosecutor; and the Registry (whose role is to support the other three organs). The functions of these organs are detailed in Part 4 of the Rome Statute.

Any amendment to the Rome Statute requires the support of a two-thirds majority of the states parties, and an amendment (except those amending the list of crimes) will not enter into force until it has been ratified by seven-eighths of the states parties. A state party which has not ratified such an amendment may withdraw with immediate effect.[35] Any amendment to the list of crimes within the jurisdiction of the court will only apply to those states parties that have ratified it. It does not need a seven-eighths majority of ratifications.[35]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ a b c The sum of (a) states parties, (b) signatories and (c) non-signatory United Nations member states is 195. This number is two more than the number of United Nations member states (193) due to the State of Palestine and Cook Islands being states parties but not United Nations member states.

References

edit- ^ a b c Article 125 of the Rome Statute Archived 19 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 18 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "United Nations Treaty Database entry regarding the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court". United Nations Treaty Collection. Archived from the original on 18 January 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ^ a b Article 126 of the Rome Statute Archived 19 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 18 October 2013.

- ^ Article 128 of the Rome Statute Archived 19 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 18 October 2013.

- ^ "The Rome Statute" (PDF). International Criminal Court. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ a b Michael P. Scharf (August 1998). Results of the Rome Conference for an International Criminal Court Archived 15 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine. The American Society of International Law. Retrieved on 31 January 2008.

- ^ Each year, to commemorate the adoption of the Rome Statute, human rights activists around the world celebrate 17 July as World Day for International Justice. See Amnesty International USA (2005). International Justice Day 2005 Archived 2 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 31 January 2008.

- ^ "Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court". United Nations Treaty Collection. 26 October 2024. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ Article 29, Non-applicability of statute of limitations

- ^ "International Criminal Court prosecutor calls for end to violence in Gaza". Reuters. Amsterdam. 8 April 2018. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ a b United Nations (1999). Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court – Overview Archived 13 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 31 January 2008.

- ^ a b Coalition for the International Criminal Court. Rome Conference – 1998[usurped]. Retrieved on 31 January 2008.

- ^ UN. General Assembly (41st sess.) (20 January 1987). "Draft Code of Offences against the Peace and Security of Mankind :: resolution /: adopted by the General Assembly". United Nations Digital Library System. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 December 2023.

- ^ Godin, Mélissa (19 February 2021). "Lawyers Are Working to Put 'Ecocide' on Par with War Crimes. Could an International Law Hold Major Polluters to Account?". Time. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ Gauger, Anja; Pouye Rabatel-Fernel, Mai; Kulbicki, Louise; Short, Damien; Higgins, Polly (2012). "The Ecocide Project - Ecocide is the missing 5th Crime Against Peace" (PDF). School of Advanced Study, University of London. Human Rights Consortium. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 December 2023.

- ^ "Final Act of the International Criminal Court". United Nations - Office of Legal Affairs. 17 July 1998. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ^ "United Nations Diplomatic Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Establishment of an International Criminal Court - Rome, 15 June - 17 July 1998 Official Records - Summary records of the plenary meetings and of the meetings of the Committee of the Whole" (PDF). United Nations - Office of Legal Affairs. Volume II. 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ^ a b Stephen Eliot Smith, "Definitely Maybe: The Outlook for U.S. Relations with the International Criminal Court During the Obama Administration", Florida Journal of International Law, 22:155 at 160, n. 38.

- ^ "UN Diplomatic Conference Concludes in Rome with Decision to Establish Permanent International Criminal Court (UN Press Release L/2889)". Archived from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Amnesty International (11 April 2002). The International Criminal Court – a historic development in the fight for justice Archived 22 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 31 January 2008.

- ^ Article 11 of the Rome Statute Archived 19 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 18 October 2013.

- ^ Assembly of States Parties (14 December 2007). "Resolution: Strengthening the International Criminal Court and the Assembly of States Parties". Archived from the original on 16 June 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2010. (310 KiB). Retrieved on 31 January 2008.

- ^ Official records of the Review Conference Archived 4 July 2011 at Wikiwix. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d "United Nations Treaty Database entry regarding the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court". United Nations Treaty Collection. Archived from the original on 23 July 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ "Reference: C.N.805.2016.TREATIES-XVIII.10 (Depositary Notification)" (PDF). United Nations. 28 October 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ^ "Reference: C.N.138.2018.TREATIES-XVIII.10 (Depositary Notification)" (PDF). United Nations. 19 March 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 November 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ "Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969: Article 18". International Law Commission. Archived from the original on 8 February 2005. Retrieved 23 November 2006.

- ^ Schindler, Dietrich; Toman, Jirí, eds. (2004). "Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court". The Laws of Armed Conflicts: A Collection of Conventions, Resolutions and Other Documents (Fourth Revised and Completed ed.). Brill. p. 1383. ISBN 90-04-13818-8.

- ^ Bolton, John R. (6 May 2002). "International Criminal Court: Letter to UN Secretary General Kofi Annan". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 31 May 2002. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ "Annan regrets US decision not to ratify International Criminal Court statute". United Nations. 8 May 2002. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ "Reference: C.N.612.2008.TREATIES-6 (Depositary Notification)" (PDF). United Nations. 27 August 2008. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ "Reference: C.N.886.2016.TREATIES-XVIII.10 (Depositary Notification)" (PDF). United Nations. 30 November 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ Jianping, Lu; Zhixiang, Wang (6 July 2005). "China's Attitude Towards the ICC". Journal of International Criminal Justice. 3 (3): 608–620. doi:10.1093/jicj/mqi056. ISSN 1478-1387. SSRN 915740.

- ^ Ramanathan, Usha (6 July 2005). "India and the ICC" (PDF). Journal of International Criminal Justice. 3 (3): 627–634. doi:10.1093/jicj/mqi055. ISSN 1478-1387. SSRN 915739. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 May 2006.

- ^ a b Article 121 of the Rome Statute Archived 19 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 18 October 2013.

Further reading

edit- Roy S Lee (ed.), The International Criminal Court: The Making of the Rome Statute. The Hague: Kluwer Law International (1999). ISBN 90-411-1212-X.

- Roy S Lee & Hakan Friman (eds.), The International Criminal Court: Elements of Crimes and Rules of Procedure and Evidence. Ardsley, NY: Transnational Publishers (2001). ISBN 1-57105-209-7.

- William A. Schabas, Flavia Lattanzi (eds.), Essays on the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court Volume I. Fagnano Alto: il Sirente (1999). ISBN 88-87847-00-2

- Claus Kress, Flavia Lattanzi (eds.), The Rome Statute and Domestic Legal Orders Volume I. Fagnano Alto: il Sirente (2000). ISBN 88-87847-01-0

- Antonio Cassese, Paola Gaeta & John R.W.D. Jones (eds.), The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court: A Commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press (2002). ISBN 978-0-19-829862-5.

- William A. Schabas, Flavia Lattanzi (eds.), Essays on the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court Volume II. Fagnano Alto: il Sirente (2004). ISBN 88-87847-02-9

- William A Schabas, An Introduction to the International Criminal Court (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2004). ISBN 0-521-01149-3.

- Claus Kress, Flavia Lattanzi (eds.), The Rome Statute and Domestic Legal Orders Volume II. Fagnano Alto: il Sirente (2005). ISBN 978-88-87847-03-1

External links

edit- Original text of the Rome Statute

- Text of the Rome Statute as amended in 2010 and 2015 – Human Rights & International Criminal Law Online Forum

- Draft Statute of an International Criminal Court, 1994

- United Nations Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Establishment of an International Criminal Court at the Wayback Machine (archived 28 December 2011)

- International Criminal Court website

- A list of the State Parties to the Rome Statute at the Wayback Machine (archived 16 June 2011)

- Parliamentary network mobilized in support of the universality of the Rome Statute