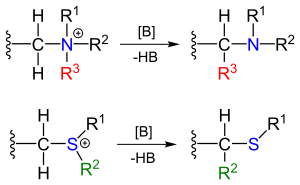

The Stevens rearrangement in organic chemistry is an organic reaction converting quaternary ammonium salts and sulfonium salts to the corresponding amines or sulfides in presence of a strong base in a 1,2-rearrangement.[1]

The reactants can be obtained by alkylation of the corresponding amines and sulfides. The substituent R next the amine methylene bridge is an electron-withdrawing group.

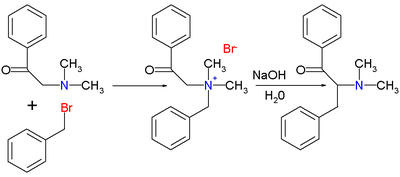

The original 1928 publication by Thomas S. Stevens[2] concerned the reaction of 1-phenyl-2-(N,N-dimethylamino)ethanone with benzyl bromide to the ammonium salt followed by the rearrangement reaction with sodium hydroxide in water to the rearranged amine.

A 1932 publication[3] described the corresponding sulfur reaction.

Reaction mechanism

editThe reaction mechanism of the Stevens rearrangement is one of the most controversial reaction mechanisms in organic chemistry.[4] Key in the reaction mechanism[5][6] for the Stevens rearrangement (explained for the nitrogen reaction) is the formation of an ylide after deprotonation of the ammonium salt by a strong base. Deprotonation is aided by electron-withdrawing properties of substituent R. Several reaction modes exist for the actual rearrangement reaction.

A concerted reaction requires an antarafacial reaction mode but since the migrating group displays retention of configuration this mechanism is unlikely.

In an alternative reaction mechanism the N–C bond of the leaving group is homolytically cleaved to form a di-radical pair (3a). In order to explain the observed retention of configuration, the presence of a solvent cage is invoked. Another possibility is the formation of a cation-anion pair (3b), also in a solvent cage.

Scope

editCompeting reactions are the Sommelet-Hauser rearrangement and the Hofmann elimination.

In one application a double-Stevens rearrangement expands a cyclophane ring.[7] The ylide is prepared in situ by reaction of the diazo compound ethyl diazomalonate with a sulfide catalyzed by dirhodium tetraacetate in refluxing xylene.

Enzymatic reaction

editRecently, γ-butyrobetaine hydroxylase,[8][9] an enzyme that is involved in the human carnitine biosynthesis pathway, was found to catalyze a C-C bond formation reaction in a fashion analogous to a Stevens type rearrangement.[8][10] The substrate for the reaction is meldonium.[11]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Pine SH (2011). The Base-Promoted Rearrangements of Quaternary Ammonium Salts. Organic Reactions. pp. 403–464. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or018.04. ISBN 978-0471264187.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Stevens TS, Creighton EM, Gordon AB, MacNicol M (1928). "CCCCXXIII.—Degradation of quaternary ammonium salts. Part I". J. Chem. Soc.: 3193–3197. doi:10.1039/JR9280003193.

- ^ Stevens, T.S.; et al. (1932). "8. Degradation of quaternary ammonium salts. Part V. Molecular rearrangement in related sulphur compounds". J. Chem. Soc.: 69. doi:10.1039/JR9320000069.

- ^ Bhakat, S (2011). "The controversial reaction mechanism of Stevens rearrangement: A review". J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 3 (1): 115–121.

- ^ M B Smith, J March. March's Advanced Organic Chemistry (Wiley, 2001) (ISBN 0-471-58589-0)

- ^ Strategic Applications of Named Reactions in Organic Synthesis Laszlo Kurti, Barbara Czako Academic Press (4 March, 2005) ISBN 0-12-429785-4

- ^ Macrocycle Ring Expansion by Double Stevens RearrangementKeisha K. Ellis-Holder, Brian P. Peppers, Andrei Yu. Kovalevsky, and Steven T. Diver Org. Lett.; 2006; 8(12) pp. 2511–2514; (Letter) doi:10.1021/ol060657a

- ^ a b Leung IKH, Krojer TJ, Kochan GT, Henry L, von Delft F, Claridge TDW, Oppermann U, McDonough MA, Schofield CJ (December 2010). "Structural and mechanistic studies on γ-butyrobetaine hydroxylase". Chem. Biol. 17 (12): 1316–24. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.09.016. PMID 21168767.

- ^ Tars K, Rumnieks J, Zeltins A, Kazaks A, Kotelovica S, Leonciks A, Sharipo J, Viksna A, Kuka J, Liepinsh E, Dambrova M (August 2010). "Crystal structure of human gamma-butyrobetaine hydroxylase". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 398 (4): 634–9. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.06.121. PMID 20599753.

- ^ Henry L, Leung IKH, Claridge TDW, Schofield CJ (August 2012). "γ-Butyrobetaine hydroxylase catalyses a Stevens type rearrangement". Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 22 (15): 4975–4978. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.06.024. PMID 22765904.

- ^ Simkhovich BZ, Shutenko ZV, Meirena DV, Khagi KB, Mezapuķe RJ, Molodchina TN, Kalviņs IJ, Lukevics E (January 1988). "3-(2,2,2-Trimethylhydrazinium)propionate (THP)--a novel gamma-butyrobetaine hydroxylase inhibitor with cardioprotective properties". Biochem. Pharmacol. 37 (2): 195–202. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(88)90717-4. PMID 3342076.