Stipan/Stjepan Konzul Istranin, or Stephanus Consul (1521 — after 1568), was a 16th-century Croatian Protestant reformator who authored and translated religious books to Čakavian dialect.[1] Istranin was the most important Croatian Protestant writer.[2]

Stjepan Konzul Istranin | |

|---|---|

1886 copper engraving of Istranin | |

| Born | 1521 |

| Died | after 1568 |

| Nationality | Croatian |

| Occupation(s) | Protestant priest and writer |

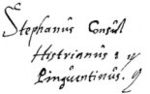

| Signature | |

| |

Biography

editIstranin was born in Buzet in 1521. At that time Buzet belonged to the Habsburg monarchy and was under the jurisdiction of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Koper, which used the Old Slavonic language for liturgical texts.[3][full citation needed]

Istranin began his career in Stari Pazin as parish priest who wrote Glagolitic texts until 1549 when he was banished for being Protestant.[1] Based on the advice of Primož Trubar Istranin went to Ljubljana in 1559 where Antun Dalmatin was already engaged to translate liturgical books.[4]

He signed his name Stipan Istrian(in) or Stephanus Consul.[5]

South Slavic Bible Institute

editThe South Slavic Bible Institute was established in Urach in January 1561 by Hans von Ungnad who was its owner and patron.[6][full citation needed] Within the institute Ungnad set up the printing press which he referred to as "the Slovene, Croatian and Cyrillic printing press".[6][full citation needed] The manager and supervisor of the Institute was Primož Trubar.[6][full citation needed]

After being invited by Trubar,[7] Istranin went to Urach where he cooperated with Antun Dalmatin who knew well Cyrillic script and who was invited to Urach to be manager of the printing press.[3][full citation needed] Trubar engaged Istranin and Dalmatin as translators to Croatian and Serbian language[8] to translate his Slovenian language translation of New Testament and print it in Latin, Glagolitic script and Cyrillic script.[9][full citation needed] The types for printing of the Cyrillic script texts were molded by craftsmen from Nuremberg.[10] The books they printed at Urach Printing House were planned to be used at entire territory populated by South Slavs between river Soča and Black Sea.[11] Trubar had idea to use their books to spread Protentantism among Croats and other South Slavs.[4]

Language used by Dalmatin and Istranin was based on northern-Chakavian dialect with elements of Shtokavian and Ikavian.[12] People from the institute, including Trubar, were not satisfied with translations of Dalmatin and Istranin.[12] For long time they tried to engage certain Dimitrije Serb to help them, but without success.[13][full citation needed] Eventually, they managed to engage two Serbian Orthodox priests, Jovan Maleševac from Ottoman Bosnia and Matija Popović from Ottoman Serbia.[13][full citation needed]

According to a list of books kept in the University Library of Tübingen, Istranin and Dalmatin printed 25,000 books in Tübingen and Urach.[14] The most important book they published was translation of New Testament based on the Trubar's translation.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Franičević, Šelec & Bogišić 1974, p. 167.

- ^ Roglić 1969, p. 134.

- ^ a b Glas 1967, p. 124.

- ^ a b Rotar 1988, p. 17.

- ^ Jembrih 2021.

- ^ a b c Society 1990, p. 243.

- ^ Urošević 1968, p. 273.

- ^ Lubotsky, Schaeken & Wiedenhof 2008, p. 280.

- ^ Društvo 1972, p. 595.

- ^ Sakcinski 1886, p. 103.

- ^ Črnja 1978, p. 117.

- ^ a b Mošin & Pop-Atanasov 2002, p. 18.

- ^ a b Матица 1976, p. 112.

- ^ Marković, Furunović & Radić 2000, p. 43.

Sources

edit- Franičević, Marin; Šelec, Franjo; Bogišić, Rafo (1974). Od renesanse do prosvjetiteljstva. Liber : Mladost.

- Roglić, Josip C. (1969). Istra; prošlost, sadašnjost. Binoza-Epoha.

- Glas (1967). Istarski mozaik. Glas Istre.[author missing][title missing]

- Sakcinski, Ivan Kukuljević (1886). Glasoviti hrvati proslih vjekova: niz zivotopisa. Naklada "Matice hrvatske".

- Črnja, Zvane (1978). Kulturna povijest Hrvatske: Temelji. Otokar Keršovani.

- Lubotsky, Alexander; Schaeken, J.; Wiedenhof, Jeroen (1 January 2008). Evidence and Counter-evidence: Balto-Slavic and Indo-European linguistics. Rodopi. ISBN 90-420-2470-4.

- Marković, Božidar; Furunović, Dragutin; Radić, Radiša (2000). Zbornik radova: kultura štampe--pouzdan vidik prošlog, sadašnjeg i budućeg : Prosveta-Niš 1925-2000. Prosveta.

- Urošević, Milivoje (1968). Pregled istorije književnosti naroda Jugoslavije do XVIII veka. Zavod za izdavanje udžbenika Socijalističke Republike Srbije.

- Društvo (1972). Bibliotekar. Društvo bibliotekara N.R. Srbije.[author missing][title missing]

- Rotar, Janez (1988). Trubar in Južni Slovani. Državna zal. Slovenije.

- Society (1990). Slovene Studies: Journal of the Society for Slovene Studies. The Society.[author missing][title missing]

- Mošin, Vladimir A.; Pop-Atanasov, Ǵorgi (2002). Izbrani dela. Menora. ISBN 9786082001166.

- Матица (1976). Review of Slavic studies. Matica srpska.[author missing][title missing]

- Jembrih, Alojz (2021). "Uz 500. obljetnicu rođenja Stipana Konzula Istranina". Hrvatska revija (1). Retrieved 7 July 2021.