Stony Creek is a 73.5-mile (118.3 km)-long[2] tributary of the Sacramento River in Northern California. It drains a watershed of more than 700 square miles (1,800 km2) on the west side of the Sacramento Valley in Glenn, Colusa, Lake and Tehama Counties.

| Stony Creek | |

|---|---|

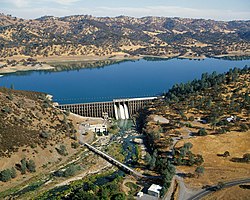

Stony Gorge Dam on Stony Creek, near Elk Creek | |

Map of the Stony Creek drainage basin | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | California Coast Ranges |

| • location | Mendocino National Forest, Colusa County |

| • coordinates | 39°22′45″N 122°38′50″W / 39.37917°N 122.64722°W[1] |

| • elevation | 1,457 ft (444 m) |

| Mouth | Sacramento River |

• location | near Hamilton City, Glenn County |

• coordinates | 39°40′38″N 121°58′23″W / 39.67722°N 121.97306°W[1] |

• elevation | 108 ft (33 m) |

| Length | 73.5 mi (118.3 km)[2] |

| Basin size | 777 sq mi (2,010 km2)[2] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | near Fruto, above Black Butte Lake[3] |

| • average | 646 cu ft/s (18.3 m3/s)[4] |

| • minimum | 0.018 cu ft/s (0.00051 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 40,200 cu ft/s (1,140 m3/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | North Fork Stony Creek, Grindstone Creek |

| • right | Middle Fork Stony Creek, Little Stony Creek |

Originating on the eastern slope of the Coast Ranges, Stony Creek flows north through an extensive series of foothill valleys before turning east across the Sacramento Valley to its confluence with the Sacramento River, about 5 miles (8.0 km) west-southwest of Chico. Stony Creek is the second largest tributary to the west side of the Sacramento River; only Cottonwood Creek is larger. Stony Creek is an important source of water for agriculture in the Orland area. The creek has native rainbow trout and historically had significant ocean-going runs of steelhead.

Stony Creek was named for the large amount of rocks and sediments it once washed down from the mountains during floods. Today, most of the sediment is trapped behind Black Butte Dam, a flood-control structure built in 1963.[5] It is labeled on some maps as "Stoney Creek" or "Stone Creek" and was historically known as the Capay River.[6]

Course

editStony Creek begins as North, Middle and South Forks in the Mendocino National Forest west of Stonyford. The North Fork, 13.4 miles (21.6 km) long, originates near the border of Lake and Glenn Counties, almost immediately flowing east into Glenn County, before turning south toward the Colusa County line.[7] The Middle Fork begins near the summit of Snow Mountain, which at 7,050 feet (2,150 m)[8] is the highest point in both Colusa and Lake Counties, in the Snow Mountain Wilderness.[9] It flows west, north then east through Lake and Glenn Counties in a large semi-circle for 15.2 miles (24.5 km), before joining with the Middle Fork in Colusa County.[10] The 13.3-mile (21.4 km) South Fork flows in a northeast direction entirely within Colusa County, joining the Middle Fork less than a quarter-mile (0.4 km) upstream of the North Fork.[10][11] The main stem of Stony Creek begins at the confluence of the North and Middle Forks.[10]

The main stem of Stony Creek flows east into Indian Valley, turning north at Stonyford and re-entering Glenn County, before receiving Little Stony Creek from the right.[10] It continues in a generally northward direction for about 20 miles (32 km) through various parallel north-south ridges and sedimentary valleys of the Coast Range foothills. At Elk Creek it is dammed at Stony Gorge Dam to form Stony Gorge Reservoir.[12] Below the dam it receives Briscoe and Elk Creeks from the left, and is crossed then paralleled for several miles by California State Route 162. It receives its largest tributary, Grindstone Creek, from the left at Grindstone Indian Rancheria. Stony Creek then turns sharply northeast, flowing through a wide valley towards Black Butte Lake.[13]

Black Butte Lake, formed by Black Butte Dam in Tehama County, is the largest reservoir on Stony Creek, covering more than 4,000 acres (1,600 ha) in the lower Coast Range foothills. A second tributary called North Fork Stony Creek joins in the reservoir from the west.[14] Downstream of Black Butte Dam surface water from Stony Creek is diverted into the Stony Creek Canal and other smaller ditches for irrigation.[15] The creek re-enters Glenn County, flowing in an east-southeast direction across the Sacramento Valley as a wide meandering stream.[16] North of Orland, the largest town in the watershed, it is crossed by Interstate 5.[17] It joins the Sacramento River south of Hamilton City and west of Chico at Sacramento river mile 190 (kilometer 306).[18]

The average unimpaired runoff of Stony Creek was 422,000 acre-feet (0.521 km3) for the period 1921 to 2003, with a maximum of 1,435,000 acre-feet (1.770 km3) in 1983 and a minimum of 17,000 acre-feet (0.021 km3) in 1977.[19] Runoff peaks in the winter and early spring, with a low summer baseflow of less than 50 cubic feet per second (1.4 m3/s).[20] Historically, flood flows of 80,000 cubic feet per second (2,300 m3/s) could be expected once every 50 years. Dams now control the winter flow in lower Stony Creek to no more than 15,000 cubic feet per second (420 m3/s), and the creek bed is often dry in the summer due to water diversions.[20]

Watershed

editThe Stony Creek watershed consists of 777 square miles (2,010 km2)[2] mostly in the Coast Range foothills and a smaller area of the Sacramento Valley. The area experiences a Mediterranean climate, with cool, wet winters and hot, dry summers. The annual precipitation, 90 percent of which falls between November and April, ranges from 32 inches (810 mm) on the valley floor to 60 inches (1,500 mm) in the headwaters.[21] The watershed above Black Butte Dam drains about 740 square miles (1,900 km2), or 95 percent of the whole.[5] Grindstone Creek drains the largest area of any tributary, at 160 square miles (410 km2), followed by Little Stony Creek at 102 square miles (260 km2).[22]

Black Butte Dam is considered the boundary between the upper and lower Stony Creek watersheds.[20] Above Black Butte Dam, most of the watershed is publicly owned in the Mendocino National Forest and various BLM and state lands, while about 96 percent of the lower watershed is privately owned.[20] Lower Stony Creek has formed an extensive alluvial fan in the Sacramento Valley which slopes downhill to the east. The alluvial fan extends about 26 miles (42 km) north to south and 14 miles (23 km) east to west, and is made up mostly of fertile, well-drained soils. Beneath the surface is the Stony Creek aquifer, whose primary source of recharge is Stony Creek. The aquifer has an estimated volume of 3 million acre-feet (3.7 km3) and is an important water source for agriculture.[23]

Water quality in upper Stony Creek is impacted by naturally occurring sources of mercury and drainage from abandoned mines, and lower Stony Creek is affected by pesticide runoff and high temperatures.[20] Black Butte Lake has also suffered water quality issues, with a toxic blue-green algae bloom occurring most recently in summer 2017.[24] The watershed in between Stony Gorge and Black Butte Dams is highly impacted by erosion, both due to overgrazing by sheep and cattle, and due to the naturally erosive geology of the area.[22]

Agriculture makes up most of the local economy, with the major crops being almonds, olives, oranges, wheat, and corn, and also dairy operations and pasture.[20] The upper watershed historically had a significant logging industry, although the amount of timber harvested saw a dramatic decline in the 1990s and has remained low since then.[20]

Geology

editNearly all of Stony Creek's course is in Glenn County, where the landscape is divided into two major terranes, or crustal fragments that have accreted to the North American continent over millions of years.[25] To the west is the Coast Range terrane, composed of folded, faulted marine rock from the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods (about 200–65 million years old).[25] Rocks of the Franciscan assemblage, consisting mainly of metamorphosed basalts and greywackes, predominate in the Coast Range.[25] The Franciscan rock is highly erosive and is the major contributor to Stony Creek's high sediment load.[22] The Stony Creek Formation, composed mainly of conglomerate, sandstone and shale, is found further east in the foothill transition zone between the Coast Ranges and Sacramento Valley.[25] The Stony Creek formation is considered the northernmost end of the Great Valley Sequence, and the inactive Stony Creek Fault, which runs parallel to and east of upper Stony Creek, marks the boundary between the two.[26]

The Sacramento Valley terrane to the east is composed of sedimentary rock overlain by thick layers of fluvial sediments, mainly clay, gravel, sand and silt.[25] About 450,000 years ago, Stony Creek's present outlet from the Coast Ranges was established, and the stream began building its large alluvial fan, or inland delta, stretching from the Coast Range foothills to the Sacramento River.[25] The delta is composed of a variety of igneous and sedimentary rocks from the Franciscan assemblage. Stony Creek has changed its course across the delta multiple times, with the current channel being established only about 10,000 years ago.[25] Until the creek was dammed in the 20th century, the fan was considered "active", or still in the process of being built by upstream sediments.[22]

Ecology

editWhile the native grasslands and riparian habitats of the Sacramento Valley have been almost entirely replaced by agriculture, the foothill and mountain areas of the Stony Creek watershed have a diversity of plant communities. The lower foothills consist of grassland, valley oak, blue oak and blue oak-foothill pine woodland, and chaparral; higher in elevation, hardwood forests of interior live oak and black oak occur along streams, and Douglas fir, white fir, ponderosa pine, and sugar pine are abundant in the mid-elevation, mixed-conifer forests of the Coast Range.[20] Red fir dominates above elevations of about 6,000 feet (1,800 m), though only a small part of the watershed is that high in elevation.[22] Most native perennial grasses in the watershed have been replaced by non-native annual grasses.[22]

Upper Stony Creek is home to a variety of native and introduced fish species, including rainbow trout, hardhead, bass, catfish and carp. There are 28 fish species in lower Stony Creek, of which 13 are native.[20] Historically, anadromous fish (salmon and steelhead migrated from the Pacific Ocean, and up the Sacramento River and Stony Creek to spawn. Dams now form an impassable barrier for fish migration to upper Stony Creek; changes in stream flow patterns and gravel mining in the old river bed have adversely affected spawning habitat in lower Stony Creek.[20]

Historically, lower Stony Creek was a braided stream with a wide rocky bed, replenished each year by large volumes of sediment eroded off its watershed. The construction of Black Butte Dam in 1963 cut off 90 percent of sediment to the lower creek[27] and has led to what has been termed the "hungry water effect", where Stony Creek continues to erode its banks while no new sediment is deposited. The erosion problem has been made worse by fluctuating water releases for irrigation.[20] As a result, the creek bed has become narrower and deeper, reducing spawning habitat for salmon and creating ideal conditions for invasive giant reed (arundo) and tamarisk.[16]

The Glenn County Resource Conservation District is undertaking an arundo and tamarisk removal program which includes both manual removal and chemical treatment.[21] The U.S. Department of Agriculture has proposed a sediment management plan for the upper watershed which would reduce the amount of sediment flowing into reservoirs by 25 percent.[22] In addition, there is a proposal to dredge gravel that has accumulated in Black Butte Lake and use it to replenish the streambed, improving habitat for native fish.[22]

Human history

editThe Native American population in what is now Glenn and Colusa Counties was approximately 10,000 before the first Europeans arrived. Most of the Native Americans spoke Wintuan languages, with the Nomlaki being the main people in the Stony Creek area.[28] Native people inhabited independent villages, with only a loose central tribal structure that existed mainly to facilitate trade. Villages were either clustered along the Sacramento River or in foothill valleys like those of Stony Creek; due to a lack of water there were no settlements on the alluvial plain, which also served as a dividing line between the "river Indians" and "foothill Indians".[29] In dry years, when forage was scarce at lower elevations, thousands of natives migrated to temporary settlements along upper Stony Creek.[29] Although the Native Americans practiced no agriculture, they frequently set brush fires which promoted the growth of certain plants they gathered for food.[22]

The beginning of European settlement was immediately prior to the California Gold Rush. During this time, Stony Creek was also known as the Capay River. The first known non-natives to visit the area were a party traveling from Oregon to Sutter's Fort in 1843.[30] Near a village on Capay River, one of the group members killed a Native American, provoking native warriors to attack them some time later.[30] John Sutter sent a force of fifty men to "punish" the natives and with the result that "great numbers of them were killed."[31] The following year, General John Bidwell explored Stony Creek from a point west of Colusa down to its mouth, for the purposes of locating suitable land grants for settlers.[31] On July 4, Bidwell camped on a hill across Stony Creek from the present day town of Elk Creek, where a monument has been erected in his honor.[6] Fur trappers soon came to the area to catch beaver, which at the time were plentiful on Stony Creek, but they got into trouble with the Native Americans there and retreated in haste.[32]

A party led by Peter Lassen in 1845 (for whom Lassen County is named) quarried grindstones on a tributary of Stony Creek, which "they took down the river for sale at Sutter's [Fort] and San Francisco." That tributary is now called Grindstone Creek.[32] General Bidwell remarked that "these grindstones... were doubtless the first "civilized" manufacture in Colusa County, if not in the entire northern part of the state."[33] In 1846 Monroeville was settled at the mouth of Stony Creek, and it grew significantly in population during the Gold Rush. One of the first steamboats to ply the Sacramento River, the California, was wrecked at a bend not far from the mouth of Stony Creek. Uriah P. Monroe salvaged the remains and used the lumber to build the Monroeville hotel, which became a popular stop along the main Sacramento River road.[6] A battle soon arose between Monroeville and Colusa, further south, to determine the county seat of newly formed Colusa County. In 1853 Colusa was officially made the county seat and Monroeville was abandoned; many residents left for St. John (founded 1856), and later Hamilton City, founded in 1905.[6]

In 1851 the Native Americans and US government signed a treaty establishing a reservation for "the tribes or bands of Indians living... on the Sacramento river from the mouth of Stone creek [sic] to the junction of Feather and Sacramento rivers, and on Feather river to the mouth of Yuba river."[34] However, the treaty was not ratified. In the next few decades repeated epidemics of introduced diseases decimated the Native American population. Many native children were kidnapped from their villages, to be sold as domestic servants or farm laborers.[35] Less than 5 percent of the native population remained by 1907, when the federal government granted them a small area of land north of Colusa.[36]

The upper Stony Creek area saw significant mining activity during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[22] By 1894 the Whitlock and Oakes mines were extracting large amounts of chrome ore, near the eponymous settlement of Chrome along upper Stony Creek. The Oakes mine operated as late as World War II (as the Black Diamond mine), helping to meet the high wartime demand for chromite.[22] Although the Stony Creek watershed was prospected for gold during the Gold Rush, gold mining never developed there on a large scale. Small amounts of copper, ochre, manganese, marble, mercury, dimension stone and coal have also been mined in the Stony Creek watershed.[22] The bed of Stony Creek is still an important source of material for aggregate mining. In 1997, more than a million tons per year was still being extracted.[25]

Settlement in both the upper and lower watershed expanded quickly in the second half of the 19th century. Elk Creek began in the 1860s as a trading post and stagecoach stop; a post office was opened there in 1872.[33] The town of Orland was founded in the early 1870s when the Southern Pacific Railroad reached the area, and soon became a major grain processing and shipping center.[37] Hugh J. Glenn, an emigrant from Missouri who arrived in California in 1849, began planting wheat in the 1860s and after several years had amassed a farming empire of 55,000 acres (22,000 ha), for which he eventually got the nickname "The Wheat King".[38] In 1891, Glenn County was named in honor of him when it was split from the northern half of Colusa County. Early dry-land farming by Glenn and others had the effect of damaging local soils; wheat yields fell considerably by the 1890s, after which cattle ranching became dominant.[38]

Starting in the 1880s, farmers attempted to irrigate using water from Stony Creek, without much success.[38] In 1906, Congress authorized the Orland Irrigation Project, the first project of the newly formed Reclamation Service (now the Bureau of Reclamation).[38] East Park Dam was built in 1908, and the first water was delivered in 1910. Stony Gorge Dam was completed much later, in 1926, after a severe drought convinced local water users to finance a second reservoir.[38] A reliable supply of irrigation water encouraged hundreds of farmers to settle in the area, replacing the former pattern of large landowners.[38] Reclamation relinquished project control to the Orland Unit Water Users' Association in 1954, and the government bonds were finally repaid in full in 1989.[39]

Dams

editThe dam and reservoir system on Stony Creek is one of the oldest in California built for agriculture and flood control. East Park Dam, impounding the Little Stony Creek tributary, is a concrete thick arch dam with a capacity of 52,000 acre-feet (64,000,000 m3) of water. The dam is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[40] The Rainbow Diversion Dam on Stony Creek diverts water into the East Park Feed Canal, which augments the water supply to East Park Reservoir.[41] Stony Gorge Dam, impounding the main stem of Stony Creek about 18 miles (29 km) downstream of East Park, has a capacity of 50,000 acre-feet (62,000,000 m3).[42] Stony Gorge is one of only a few slab and buttress Ambursen-type dams constructed by the Bureau of Reclamation.[43] Both East Park and Stony Gorge are used primarily for irrigation storage, with flood control as an incidental benefit.[44]

The earth-filled Black Butte Dam was constructed in 1963 by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and is the main flood control facility for lower Stony Creek. Black Butte is not part of the Orland project, but can be used to store extra irrigation water in wet years.[45] Its original capacity was 160,000 acre-feet (200,000,000 m3), but heavy sediment build-up had reduced this to 135,000 acre-feet (167,000,000 m3) by 1997, and the reservoir continues to lose about 700 acre-feet (860,000 m3) per year to sedimentation.[21] Downstream of Black Butte is the Orland project's Northside diversion dam, which diverts water into 17 miles (27 km) of main canals and 139 miles (224 km) of laterals, serving about 20,000 acres (8,100 ha) of fertile farmland.[46]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Stony Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 1981-01-19. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ^ a b c d "USGS National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data via National Map Viewer". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2017-09-24.

- ^ "USGS Gage #11387000 Stony Creek near Fruto, CA". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1901–1978. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ^ "USGS Gage #11387000 Stony Creek near Fruto, CA". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1901–1978. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ^ a b H.T. Harvey & Associates (2007-02-23). "Stony Creek Watershed Assessment, Volume 1: Lower Stony Creek Watershed Analysis" (PDF). Glenn County Resource Conservation District. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ^ a b c d Kyle et al. 2002, p. 98.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Saint John Mountain, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ^ "Snow Mountain East". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 1981-01-19. Retrieved 2017-10-23.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Potato Hill, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ^ a b c d United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Stonyford, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Fouts Springs, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Elk Creek, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Chrome, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Sehorn Creek, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Black Butte Dam, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ^ a b "Stony Creek Pre and Post Dam". Glenn County Resource Conservation District. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Kirkwood, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Ord Ferry, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ^ "California Central Valley Unimpaired Flow Data" (PDF). California Department of Water Resources. May 2007. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Stony Creek Watershed" (PDF). Sacramento River Watershed Program. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ^ a b c "Lower Stony Creek Watershed Landowner's Manual" (PDF). Glenn County Resource Conservation District. 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l H.T. Harvey & Associates (2007-02-23). "Stony Creek Watershed Assessment, Volume 2: Existing Conditions Report" (PDF). Glenn County Resource Conservation District. Retrieved 2017-10-23.

- ^ Staton, Kelly (May 2006). "Stony Creek Groundwater Recharge Investigation, 2005, Glenn County, California" (PDF). County of Glenn. Retrieved 2017-10-12.

- ^ "Black Butte Lake clear of blue-green algae bloom". KDRV News. 2017-06-12. Retrieved 2017-10-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Mineral land classification of concrete-grade aggregate resources in Glenn County, California" (PDF). Division of Mines and Geology, California Department of Conservation. 1997. Retrieved 2017-10-23.

- ^ "Geology of the Northern Sacramento Valley, California" (PDF). California Department of Water Resources. 2014-09-22. Retrieved 2017-10-23.

- ^ Mount 1995, p. 326.

- ^ "Nomlaki". Elder Creek Oak Woodland Preserve. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ^ a b McComish & Lambert 1918, p. 39.

- ^ a b McComish & Lambert 1918, p. 24.

- ^ a b McComish & Lambert 1918, p. 25.

- ^ a b McComish & Lambert 1918, p. 26.

- ^ a b Kyle et al. 2002, p. 99.

- ^ "Treaty made and concluded at Camp Colus, on Sacramento River, California, September 9, 1851, between O.M. Wozencraft, United States Indian Agent, and the Chiefs, Captains and Head Men of the Colus, Willays, &c. Tribes of Indians". California State Military Museums. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ^ "A shameful past: How bloody raids and slave trade led to California's rise as an ag powerhouse". Chico News & Review. 2013-08-01. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ^ McComish & Lambert 1918, p. 49.

- ^ Kyle et al. 2002, p. 100.

- ^ a b c d e f Autobee, Robert (1993). "Orland Project". U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ^ Arrigoni, Barbara (2007-10-06). "Orland celebrates first 100 years of federal irrigation project". ChicoER. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ^ "East Park Dam". U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Retrieved 2017-10-23.

- ^ "Rainbow Diversion Dam". U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Retrieved 2017-10-23.

- ^ "Stony Gorge Dam". U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Retrieved 2017-10-23.

- ^ Billington, Jackson & Melosi 2005, p. 79.

- ^ "Environmental Assessment: Safety of Dams Modifications to Stony Gorge Dam". U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. 2004-12-14. Retrieved 2017-10-23.

- ^ "Water Management" (PDF). Stony Creek Quarterly. 2 (2). Glenn County Resource Conservation District. 2006. Retrieved 2017-10-23.

- ^ "Orland Project". U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Retrieved 2017-10-23.

Works cited

edit- Billington, David P.; Jackson, Donald Conrad; Melosi, Martin V. (2005). The History of Large Federal Dams: Planning, Design and Construction. Government Printing Office. ISBN 0-16072-823-1.

- McComish, Charles Davis; Lambert, Rebecca T. (1918). History of Colusa and Glenn Counties, California: With Biographical Sketches of the Leading Men and Women of the Counties who Have Been Identified with Their Growth and Development from the Early Days to the Present. Historic Record Company.

- Mount, Jeffrey F. (1995). California Rivers and Streams: The Conflict Between Fluvial Process and Land Use. University of California Press. ISBN 0-52091-693-X.

- Kyle, Douglas E.; Rensch, Hero Eugene; Rensch, Ethel Grace; Hoover, Mildred Brooke (2002). Historic Spots in California (5 ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-80477-817-5.