The Sydney International Regatta Centre (SIRC), located in Penrith, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, is a rowing and canoe sprint venue built for the 2000 Summer Olympics.[1] It is now a popular sporting venue, with the Head of the River Regatta held annually.

| Sydney International Regatta Centre (SIRC) | |

|---|---|

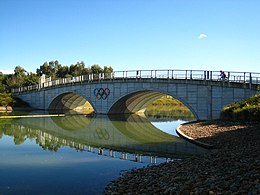

Sydney International Regatta Centre Bridge | |

| Location | Penrith, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 33°43′21″S 150°40′16″E / 33.7224°S 150.6712°E |

| Type | Artificial lake, rowing lake |

| Built | 1995 |

| Max. length | 2,300 metres (7,500 feet) |

| Max. width | 170 metres (560 feet) |

| Surface area | 98 hectares (240 acres) |

| Average depth | 5 metres (16 feet) |

Description

editThe Sydney International Regatta Centre (SIRC) is a 196-hectare outdoor sport and entertainment facility, for both on and off the water activities.[2] SIRC was built as part of the larger Penrith Lakes Scheme consisting of 2000 hectares of former quarrying land, redesigned to accommodate 6 major lakesincluding the Sydney International Regatta Centre. Its construction was finalised in 1995 prior to the Sydney 2000 Summer Olympics.[3]

The Sydney International Regatta Centre contains outdoor and undercover exhibition spaces, multiple conference rooms and a spectator grandstand, architecturally designed by Woods Bagot which seats 1000 spectators undercover.[4]

SIRC consists of a 2300m competition lake, a 1500m warm up lake and a 5 km cycling and running loop amongst other prominent features.[2] The regatta centre is utilised for activities such as; rowing, canoeing, triathlons, catch and release fishing competitions, walking/jogging/rollerblading along the 5 km track surrounding the course, scuba diving lessons and corporate events and functions.[5]

The Sydney International Regatta Centre averages over 50 000 visitors a month, resulting in over half a million international and domestic visitors annually.[6]

Defqon.1 Weekend Festival Australia was also held at SIRC; as a newly established and reasonably popular hard dance music event Defqon.1 Festival requires a large venue which is somewhat removed from residences, making the Regatta Centre an ideal location.

In May 2012 the second round of the UIM world powerboat championships for Blown Alcohol and 6 Litre boats was held here over 3 days and will return in 2013

It is part of the Penrith Lakes.

The site is managed by NSW Sport and Recreation.

Specifications

editThe Sydney International Regatta Centre (SIRC) is a 196-hectare on and off water, outdoor activity centre. It consists of 60-hectares of landscaping, and 98-hectares of water surface making up the 2300m competition lake and 1500m warm up lake with width of 170m and average depth of 5m.[7] Under the freshwater, native aquatic plants totalling over 50,000 were planted.[8] The landscaping includes a 5 km running and cycling loop, and along the track over 30,000 native trees and shrubs have been planted.[8] The competition lake consists of nine competition lanes spanning 13.5m wide.[7]

SIRC's island capacity is at 20,000 people, and overall venue capacity is at 30,000. However, SIRC can host up to 50,000 people upon approval of an application.[9]

Within the Pavilion and Boatshed facilities located on the island there are 4 conference rooms equipped with audio and visual equipment, as well as a Lakeside function room. Furthermore, the grandstand and pavilion seats 1000 people.[10]

Parking at SIRC provides for 2000 cars and is situated off of Old Castlereagh Road.[8]

History

editThe concept to convert the gravel and sand quarries of Penrith into recreational lakes was initially conceived in 1968.[11] In conjunction with the NSW Government's facilitation, land holding companies merged their quarrying operations and acreage establishing a joint venture forming the Penrith Lakes Development Corporation (PLDC) in 1980.[11] Under the Environment Planning and Assessment Act they passed the Sydney regional Environmental Plan No.11.[11] The NSW Government unveiled the 2000-hectares of aquatic based entertainment facility in 1986.

The 196-hectare Sydney International Regatta Centre (SIRC) was completed in 1995 via the Penrith Lakes Scheme consisting of 2000-hectares of former quarrying land.[12] Woods Bagot, Blue Scope Steel (Formally known as BHP Steel), North Shore Paving Co Pty Ltd, and Conybeare Morrison were among the companies which contributed to the creation of the facilities present on the regatta centre.

The goal of the Penrith Lakes Scheme was to turn the area into a recreational space for the local community. SIRC was staged first for its use in the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games.[13]

Water management

editThe Sydney International Regatta Centre (SIRC) draws a significant amount of water from the Nepean River system.[14] It has been used as a case study for innovative sustainable methods of water management. SIRC's “water quality has been suitable for primary contact 95% of the time since 1996”.[15] This was met for majority of the year with minimum intervention, recurrent budget expenditure and no chemical treatment. As a shallow, freshwater lake with depth of 5m, SIRC is at risk of water contamination by algae and exotic macrophytes. The lakebed is planted with over 50,000 native aquatic plants such as ribbon-weed (Vallisneria Americana) and was introduced with bass (Macquaria novemaculeata) fingerlings “to establish a ‘balanced aquatic ecosystem’ with a healthy aquatic plant assemblage, capable of out-competing nuisance algae and ‘exotic’ macrophytes.” [16][15]

The growth of blue-green algae (Oscillatoria) along the base of the ribbon-weed at SIRC resulted in the defoliation of 1997. Additional causes include; low dissolved oxygen levels, increased turbidity, rising water levels and stratification. To physically remove the floating foliage on the surface of the water, ribbon-weed aquatic weed harvesters were implemented.[15]

Sustainability

editThe Sydney International Regatta Centre (SIRC) was developed with a focus on Economically Sustainable Development (ESD) specifically in regard to flora and fauna, people, construction, energy, water, air, soil and waste management.[17][8] Ways in which they promoted this focus are:

- Flora and fauna: Over 30,000 native trees and shrubs including 160 Eucalyptus benthamii were planted at SIRC.[8]

- People and their environment: The Pavilion was designed and placed to complement the natural environment surrounding the site. Its capability to retract seating and roofing provides the Pavilion a multipurpose capacity. Additionally, to minimise the environmental implications of bitumen car parks, SIRC parking lot is predominantly grassed.[8]

- Construction materials: The Pavilion is constructed of corrugated iron, recycled timber, timber and turpentine from managed regrowth forests, and steel. Concrete and bitumen were recycled and reused for the new concrete slabs and bitumen paving. Furthermore, recovered crushed sandstone and existing topsoil from the site was amassed and reclaimed during construction.[8]

- Energy: Solar panels installed atop the finishing tower feeds into the local grid. Consequently, saving 2.8 tonnes of CO2 gas emission per year. The lighting used is highly efficient low energy fixtures connected to motion and daylight sensors. To reduce the necessity of air conditioning, the Pavilion takes advantage of cool summer winds by utilising the east–west orientation. Whereas the overhanging roof allows winter sun to penetrate from the north.[8]

- Water: All water source points were installed with flow control devices and efficiency maximising fittings for minimal water usage. Irrigation at SIRC is minimal, however sourced from select areas of the lake when necessary. Thus, reducing overall water usage.[8]

- Air: Despite the Pavilion being designed to maximise natural ventilation, the air conditioning units installed are HCFC (R22) small package refrigerant.[8]

- Soil: Existing onsite topsoil was recycled during construction, and appropriate stormwater run offs were implemented to mitigate sedimentation and erosion. Additionally, revetments were implemented along the course banks to minimise return wake, soil erosion and distribution of bank material.[8]

- Waste management: during construction measures such as; careful consideration for materials ordered, waste disposal and an on-site worm farm for food scraps were utilised. Currently, SIRC upkeeps the use of recycling bins during its operation.[8]

Past events

editThe Sydney International Regatta Centre has hosted various recreational and sporting activities since its completion in 1995. Events include:

- The Australian Rowing Championships: SIRC has hosted the Australian Rowing Championships on eleven occasions as of May 2020. 1996, 2000, 2005, 2008 and from 2013 to 2019.

- NSW Schoolboy/Schoolgirl Head of The River (HOTR): Schoolboy and Schoolgirl HOTR has been held at the regatta centre beginning in 1997.

- In 2013, an assignment on the sixth season of The Mole took place at this venue, which required the contestants to collect a number of inflatable balls on a set course that would win them some money for the kitty.[18]

- Defqon.1: Held between 2008 and 2018, Defqon.1 was “postponed indefinitely” (as of May 2019) after drug related complications which occurred at SIRC in 2018.The 2018 Defqon.1 Music Festival was attended by approximately 30,000 people, of which approximately 700 people sought medical assistance, and from 355 police conducted searches, 69 people were allegedly found with illicit substances.[19] In light of the two fatalities recorded, NSW Premier as of September 2018 Gladys Berejiklian, promised to “do everything we can to shut this down”,[20] in reference to Defqon.1’s return to the Sydney International Regatta Centre. Member for Penrith as of September 2018, Stuart Ayres declared that the Sydney International Regatta Centre “will not be hosting Defqon.1 into the future.”.[19]

Sydney 2000 Olympic events

editDuring the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games, the Regatta Centre held the rowing events and the canoe sprint events.

| Canoe Sprint | ||

|---|---|---|

| C-1 500m | Men | |

| C-1 1000m | Men | |

| C-2 500m | Men | |

| C-2 1000m | Men | |

| K-1 500 | Men | Women |

| K-1 1000m | Men | |

| K-2 500m | Men | Women |

| K-2 1000m | Men | |

| K-4 500m | Women | |

| K-4 1000m | Men |

| Rowing | ||

|---|---|---|

| Single sculls | Men | Women |

| Coxless pair | Men | Women |

| Double sculls | Men | Women |

| Lwt double sculls | Men | Women |

| Coxless four | Men | |

| Quadruple sculls | Men | Women |

| Eight | Men | Women |

| Lwt coxless four | Men |

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ 2000 Summer Olympics official report. Volume 1. p. 389.

- ^ a b Penrith Lakes. (2015). History of the Penrith Lakes Scheme. Sydney, Australia. 1–2. Retrieved from http://admin.penrithlakes.com.au/content/2015/03/HISTORY-OF-THE-PENRITH-LAKES-SCHEME_MARCH-2015.pdf

- ^ Godden Mackay Logan. (2010). Penrith Lakes scheme conservation management plan. Sydney, Australia. Penrith Lakes Development Corporation. 1. 32–145. Retrieved from http://admin.penrithlakes.com.au/content/2015/03/Penrith-Lakes-Scheme-CMP-Final-Report_Reformatted-November-2010.pdf

- ^ BHP Steel. (2003). Sydney International Regatta Centre & Whitewater Stadium. Sydney, Australia. Olympic Case Study. Retrieved from http://www.bluescopesteel.com.au/files/sydney_international_regatta_centre.pdf

- ^ BHP Steel. (2003). Sydney International Regatta Centre & Whitewater Stadium. Sydney, Australia. Olympic Case Study. Retrieved from http://www.bluescopesteel.com.au/files/sydney_international_regatta_centre.pdf

- ^ Olympic Co-ordination Authority. (2000). Environment report 1999. Sydney, Australia. 1, 22–25. Retrieved from https://library.olympic.org/Default/digitalCollection/DigitalCollectionAttachmentDownloadHandler.ashx?documentId=166762&skipWatermark=true

- ^ a b NSW Office of Sport. (2019) Our lakes. Sydney, Australia. Retrieved from www.sport.nsw.gov.au/regattacentre/facilities/lakes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Olympic Co-ordination Authority. (1999). Compendium of ESD initiative and outcomes. Sydney, Australia. 2,100–105. Retrieved from www.sydneyolympicpark.com.au/-/media/files/sopa/sopa/publications/environmental-publications/esd_compendium_1999.pdf?la=en&hash=EF6EE2421902A120B5650FD86197726DF65525B5.

- ^ NSW Government Architects Office. (2014). Penrith Lakes parkland draft vision plan. Sydney, Australia. 1, 9–61. Retrieved from www.penrithlakeseec.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Draft_Vision_Plan_Penrith_Lakes_Parklands_-_FULL-1.compressed.pdf.

- ^ Godden Mackay Logan. (2010). Penrith Lakes scheme conservation management plan. Sydney, Australia. Penrith Lakes Development Corporation. 1. 32–145. Retrieved from http://admin.penrithlakes.com.au/content/2015/03/Penrith-Lakes-Scheme-CMP-Final-Report_Reformatted-November-2010.pdf

- ^ a b c Penrith Lakes. (2015). History of the Penrith Lakes Scheme. Sydney, Australia. 1–2. Retrieved from http://admin.penrithlakes.com.au/content/2015/03/HISTORY-OF-THE-PENRITH-LAKES-SCHEME_MARCH-2015.pdf

- ^ Godden Mackay Logan. (2010). Penrith Lakes scheme conservation management plan. Sydney, Australia. Penrith Lakes Development Corporation. 1. 32–145. Retrieved from http://admin.penrithlakes.com.au/content/2015/03/Penrith-Lakes-Scheme-CMP-Final-Report_Reformatted-November-2010.pdf

- ^ "Penrith Lakes". www.penrithlakes.com.au. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Paterson, I. (21 September 2015). Quarry closes as plans to build the Penrith Lakes scheme begin to take shape. Sydney, Australia. The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved from https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/newslocal/penrith-quarry-closes-as-plans-to-build-the-penrith-lakes-scheme-begin-to-take-shape/news-story/f45c7a6c76995ad3dd54bd8ee394b121

- ^ a b c Roberts, D. E., Sainty, G. R., Cummins, S. P., Hunter, G. J. & Anderson, W. J. (2001). Managing submersed aquatic plants in the Sydney International Regatta Centre, Australia. Aquatic Plant Management, 39, 12–17. Retrieved from www.apms.org

- ^ McCreary, N. (1991). Competition as a mechanism of submersed macrophyte community structure. Aquatic Botany. 41, 177–193. doi:10.1016/0304-3770(91)90043-5

- ^ Baker, B. (2020). Introducing urban sustainability at Penrith Lakes. Sydney, Australia. 1. CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems. Retrieved from www.regional.org.au/au/soc/2002/2/baker.htm

- ^ "The Mole (Australia season 6) - Episodes 10 and 11". 7 August 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

- ^ a b Begley, P. & Evans, M. (16 September 2018). ‘Absolutely tragic’: Premier vows to shut festival down after two overdose deaths. Sydney, Australia. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved from https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/two-dead-after-defqon-music-festival-overdoses-at-penrith-20180916-p50422.html

- ^ Rota, G. (30 May 2019). Defqon.1 festival ‘postponed indefinitely’, nine months after reveller deaths. Sydney, Australia. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved from https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/music/defqon-1-festival-postponed-indefinitely-nine-months-after-reveller-deaths-20190530-p51syl.html