Vatican Library, Syr. 559 is a Syriac manuscript produced around 1220. It is an evangeliary containing the text of the Peshitta. It is one of the few well illustrated Middle Eastern Christian manuscripts from the 13th century.

There is some dispute about the reading of the date, some scholars arguing for 1220, while others argue for 1260.[4]

The location where the manuscript was created is the Jazira region near Mosul, at the monastery of Deir Mar Mattai.[5]

The writing is in Estrangela script.[6] It is considered as a near twin of Syriac Gospels, British Library, Add. 7170 manuscript, also attributed to the northern Iraq (Jazira region).[6]

The manuscript is derived from the Byzantine tradition, but stylistically has a lot in common with Islamic illustrated manuscripts such as the Maqamat al-Hariri, pointing to a common pictorial tradition that existed since circa 1180 CE in Syria and Iraq.[6] Some of the illustrations of these manuscript have been characterized as "illustration byzantine traitée à la manière arabe" ("Byzantine illustration treated in the Arab style").[6]

Notably, Constantine and Helena are shown in post-Seljuk clothing, a style attributable to the influence of local Turkic polities.[1][7]

-

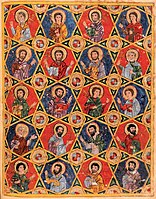

Twenty of the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste

References

edit- ^ a b Snelders 2010: "A similar assimilation to local fashion may be presumed for the representation in the Vatican lectionary, in which the genuine Byzantine imperial dress worn by Constantine and Helena has been somewhat transformed in its appearance to meet the dress code of local rulers. Although the image has retained the traditional imperial Byzantine loros-costume, the usual headdress of the imperial couple has been replaced by a type of crown reminiscent of that worn by rulers in the Great Seljuk successor states and encountered in contemporary Islamic art."

- ^ Stewart, Angus (2019). 18 Hülegü: the New Constantine? in "Syria in Crusader Times". Edinburgh University Press. p. 323. doi:10.1515/9781474429726-022.

- ^ Stewart, Angus (2019). 18 Hülegü: the New Constantine? in "Syria in Crusader Times". Edinburgh University Press. p. 326-327. doi:10.1515/9781474429726-022.

p.326: image (...) p.327: When the work was completed Hülegü was at most three years old, and possibly not yet even conceived. (...) p.328 The identification of these figures as being specifically 'Mongol' is in itself questionable. Their costume, for example, is only 'Oriental' in the sense of being Near Eastern – the Byzantine loros-costume, but with robes decorated with tiraz bands common to the Islamic world, and with 'Seljuq' style crowns. Similarly, when analysed artistically, the images fit into a distinctly Near Eastern mould, having much in common with contemporary work from northern Syria and Mesopotamia produced in an Islamic milieu.

- ^ Snelders 2010: "The Vatican lectionary was copied by the scribe Mubarak ibn David ibn Saliba ibn Yacqub, a monk at the monastery, who came from the nearby village of Bartelli. The date of completion is also given in the colophon, but it has been subject to debate. For a long time, the date mentioned was interpreted as A.G. 1531, corresponding to A.D. 1220. More recently, scholars have argued that it should perhaps be read as A.G. 1571, that is A.D. 1260. Pending the results of study by epigraphic specialists, it can be argued that this relatively slight chronological difference does not impact heavily on the aims of the present art-historical research."

- ^ Snelders 2010, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b c d The Glory of Byzantium: Art and Culture of the Middle Byzantine Era, A.D. 843-1261. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1997. pp. 384–385. ISBN 978-0-87099-777-8.

- ^ Cambridge History of Christianity Vol. 5 Michael Angold p.387 Note 34: Vatican Syr.559 Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-81113-9 "In May 1260, a Syrian painter gave a new twist to the iconography of the Exaltation of the Cross by showing Constantine and Helena with the features of Hulegu and his Christian wife Doquz Khatun"

Sources

edit- Snelders, B. (2010). Identity and Christian-Muslim interaction : medieval art of the Syrian Orthodox from the Mosul area. Peeters, Leuven.

- The Glory of Byzantium: Art and Culture of the Middle Byzantine Era, A.D. 843-1261. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1997. pp. 384–385. ISBN 978-0-87099-777-8. (PdF)